Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Janice Lee: In your other life, you’re an architect and furniture designer. I’m interested in how this work and mode of thinking influences your stories. For example, the preciseness of your language, the constructedness of your stories as rigid and stable structures, your attention to spatial details and spatial relationships, and the existence of people and objects in physical environments rather than in relation to each other.

Luis Panini: My academic background has not only influenced the way in which I think about stories before I actually write them but also it has made me think about overall structures when I am constructing (not writing) a book, whether is a collection of short fiction, a novel, a book of poems or some piece of writing that does not necessarily falls into these ankylosing categories. Spatial awareness is very important for me since it is ultimately where the “game is played” and this is why I frequently try to inject some sort of symbolic meaning to both, the spaces my characters inhabit and the objects they come in contact with. In a way, what I am trying to accomplish is to integrate these “architectural objects” into the narrative in such a way that these become as important as the characters or the story itself. It is about translating the mere functionality of a space or an object into an emotional component in the writing process or how this space or object is acknowledged and assimilated by the reader. Duchamp’s “Fountain” comes to mind. He managed to transform a simple urinal into an object charged with many layers of meaning by placing it within the confines of a “sacred space.” Outside the museum, Duchamp’s piece is nothing but a urinal. Inside the museum is everything but a urinal because the reading conditions of this object have been transgressed. This is the sort of relationships I like to establish between my characters and the space they move about.

JL: You’ve described your stories as vignettes or fragments, and I think they operate in this way, but too, at the same time, they seem like such self-contained and intentionally built structures that do have set boundaries. Can you talk a bit more about the general shape of your individual stories?

LP: I did refer to those texts (the ones collected in my second book) as vignettes or fragments because that is truly what these are. They are absolutely self-contained pieces of writing. I like to think that the most interesting building block in writing is not the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, etc. but the fragment, because a fragment does not require a beginning or an end, it does not need to tell a whole story to work, it does not have to acknowledge the fragment that precedes it or follows it and I find this to be truly liberating, a sense that I do not get when I take a different approach. About a year or two ago I finished writing a book that deals with memory and it is comprised of more than one hundred fragments. There are two versions of that book. In one version the fragments follow a chronological order of events and in the other version the fragments appear in the order in which they were written, the order in which I remembered a loved one who died recently. I chose to write about that story through fragments because in a way I wanted to emulate the mechanisms of memory and a fragmentary approach made perfect sense since I could experiment with the elasticity of the overall structure (or lack of one) by allowing a virtually infinite number of permutations. This also allowed me to set very strict boundaries on a fragment bases that I had to respect as I was writing each line. Every time I deviated in any way from those boundaries, the fragment did not work. It felt like an ill-conceived part of a whole. Through this method of writing I learned about the shape of not just individual stories but also how these can be connected in a book and how they interact among themselves by borrowing, cannibalizing from each other, etc. A book composed of fragments can be dozens of different books, only limited by the sequence you end up choosing.

JL: I know you are a Béla Tarr fan too, and I find that there are some resonances in your work with Tarr’s fans. For example, the focus in your stories is often on a person’s existence in a space or situation, and the story settles in on the details of the environment, constructing a scene that becomes a sort of story, rather than a story that is based on action and resolution. This reminds me of the indifference of the camera in Tarr’s films too, where often the setting is there before a character enters, and remains there after the character is gone. What are your thoughts on this observation?

LP: Sometimes I think that filmmakers are the ones who truly influence my creative process and writing methods, much more than literature in general or specific writers and books, and this has nothing to do with the fact that I live in Los Angeles, a city in which if you mention that you are a writer most people immediately ask you what screenplays have you written. Béla Tarr is one of these auteurs (I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed seeing that old man peeling potatoes in “The Turin Horse”), but also I am fascinated with the way other directors choose to tell stories, like Michael Haneke, Yorgos Lanthimos, and my personal favorite Ruben Östlund. I am not trying to say that my literary work has a cinematic quality or that it could easily be translated onto the screen, but this element becomes quite obvious since I tend to favor heterodiegetic narrators in most of my texts. I like to take it to the extreme, turning them into machine-like narrators which can be perceived as actual cameras panning through multiple rooms in a residence to create some sort of long shot composed by zoom-ins, abrupt cuts, blurs, etc. My vignette titled “The Event” is an example of this. After the character has “disappeared” in a very tragic way the camera goes back into the apartment where it all began and stays in recording mode to capture the solitude of the space, which to me is far more important than the demise of the actual character. In another vignette the narrator also acts as a camera that moves inside of a mansion to capture many of the possessions of a lonely man dying of complications related to an immunological disease. I was not interested in that man’s story specifically, but in how I could construct one by describing the pieces of furniture and ornaments he owns, the art hanging on his walls, and the materials and finishes of his home. I guess by doing this I am trying to illustrate some sort of terror that sometimes keeps me awake at night, the fact that after one dies everything else remains in its place, unaltered, because we are that insignificant. And it is this sense of pervasive malaise what informs most of my writing.

JL: I’m affected deeply by level of compassion and human dignity present in Tarr’s fans. On this subject, Andras Balint Kovacs writes:

“The man, whose philosophy despises ‘humanist’ feelings like compassion and pity, suddenly and certainly unwillingly, manifests the deepest compassion for a helpless living being, a beaten horse. This event, says Krasznahorkai, is ‘the flashing recognition of a tragic error: after such a long and painful combat, this time it was Nietzsche’s persona who said no to Nietzsche’s thoughts that are particularly infernal in their consequences.’ This is the example which leads to a conclusion about the universality of this feeling: ‘if not today, then tomorrow… or ten, or thirty years from now. At the latest, in Turin.’ … an attitude or an approach to human conditions, which Tarr fundamentally shares with Krasznahorkai… Both authors have a fundamentally compassionate attitude toward human helplessness and suffering in whatever situation it may manifest itself, and of whatever antecedent it may be the result.”

In Tarr films, compassion can exist without moral judgment, or, in other words, “In the Tarr films human dignity is not based on morality. It is based on the fact that in spite of their absolutely hopeless and desperate situations the characters remain what they are, however low what they are brings them.”

This simultaneous closeness and distancing, this empathy is ever-present in your stories for me too. For example, in “Mathematical Certainty,” there is a deep care in the description of the hat, but also in the generous curiosity afforded to the man with the brain tumor. I also recently heard Lydia Davis talk about description, and said something like, “In order to describe something, you have to love it. Even if it’s ugly, like an old shoe, you have to love it in a way to really describe it.” The preciseness of your language and the kind of curiosity afforded by such a detail as the length between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, seems like a generous gesture in a way. What are your thoughts?

LP: I believe empathy and compassion is what drove me to write the vignettes included in my second book, as strange as that may sound given the dark nature of the overall subject matter of those texts, which is ill will. In fact, I can pinpoint the exact moment that acted as the catalyst. Back in 2006 there was a terrible brush fire, which consumed an enormous area near Los Angeles. For some reason that I yet have to comprehend a news show chose to broadcast a recording with no “viewer discretion advised” warning beforehand. I saw the body of a fallen hare partly carbonized. It was still moving, shaking the rear legs, convulsing, agonizing. And it affected me so much because animal suffering is something I simply cannot deal with. So this visceral reaction prompted me to explore this feeling in different ways, in fact so many that soon became a book about ill will. Ill will towards animals, patients with terminal diseases, sexual partners, art, even towards the reader. The main character in “Mathematical Certainty” is a man who soon will die of a brain tumor he has chosen not to have surgically removed. Instead, he decides to buy a white hat to conceal, maybe in an unconscious way, this organic tissue developing inside of him. Growing up in a predominantly catholic environment I heard many people say that the real reason why a man or a woman got cancer was the result of divine punishment, as if sinful behavior (whatever that means) could trigger it. So, in a way, that particular vignette is about religious ill will, the supposed shame caused by the disease, thus the comparison between the hat and a crown of thorns. Again, I was not too interested in the life of this character, but in presenting a juxtaposition of elements, such as a man fully dressed in white with something truly dark growing inside of his skull, and more so in determining the distance between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, because those particularities or insignificances are what fuel my desire to write. I don’t want to write about the victims of a serial killer or the reasoning behind his actions, instead I want to write about the way in which this terrible person peels potatoes.

READ MORE >

The Conductor and Other Tales

The Conductor and Other Tales Diptychs + Triptychs + Lipsticks + Dipshits

Diptychs + Triptychs + Lipsticks + Dipshits  Because

Because Taipei

Taipei Great Guns

Great Guns Videotape

Videotape The Best American Comics 2013

The Best American Comics 2013

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

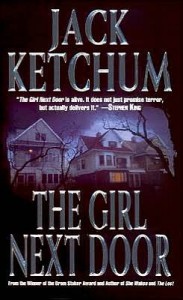

The Girl Next Door

The Girl Next Door