When I visit Brooklyn, there is Brooklyn, and then there is the idea of Brooklyn I have before I visit Brooklyn, and then there is the idea of Brooklyn the people I’m visiting in Brooklyn have of Brooklyn, and then there is the idea of Brooklyn the people I tell I’m visiting Brooklyn have of Brooklyn, and there are the Brooklyn streets and the Brooklyn people and the Brooklyn buildings, and Manhattan is across the river, and there is the idea of Brooklyn as part of New York City, and there is the idea that Brooklyn isn’t a part of New York City, because New York City is Manhattan, and when I read Edward Falco I visit a Williamsburg where it is not safe to walk the streets, and when I visit Williamsburg it is very safe to walk the streets, even alone at night, and when I walk through a neighborhood full of Hasidic Jews walking on a Saturday, the people I’m with tell me how it is to live in a neighborhood of Hasidic Jews walking on a Saturday, but I don’t know anything about what it’s like to be a Hasidic Jew walking on a Saturday, and when I’m with people who like to talk about literature, Brooklyn is a place where everyone talks about literature, but when I’m not with people who like to talk about literature, no one in Brooklyn is talking about literature, and when I read about Brooklyn in newspapers I hear stories about Brooklyn trends, such as it’s cool to have a potbelly, but when I’ve been in Brooklyn, I’ve never met anyone who believes it’s cool to have a potbelly, and what I’m wondering is: What is Brooklyn?, and: What does a person mean when a person is saying Brooklyn to me?, and: If I only visit Brooklyn but never live in Brooklyn, do I know very much about what Brooklyn is?, and: If I lived in Brooklyn but never visited other places, how would I have any idea of what Brooklyn might be without having other places against which to compare Brooklyn?, and: If I grew up in Brooklyn, would Brooklyn be Brooklyn now or the Brooklyn I knew then or both or neither, and: If I didn’t grow up in Brooklyn but I lived in Brooklyn, would Brooklyn be Brooklyn now or the Brooklyn I imagine from then or both or neither, and: If I’ve never lived in Brooklyn, but I frequently visit Brooklyn, is Brooklyn the Brooklyn I visit or the Brooklyn I imagine Brooklyn to be when I’m not there or the Brooklyn I imagine Brooklyn used to be or the thing I think Brooklyn can do for me or the thing I think Brooklyn is doing for other people or none of these things or all of these things?, and: Why is it always I’m wanting to think about my idea of Brooklyn and never I’m thinking about my idea of the place I really live, which seems too out-of-the-way and inconsequential to mean anything to anyone, or even to mention to anyone I meet in Brooklyn, and what does that say about my idea of Brooklyn?

I admire the way the stories in Matt Bell’s How They Were Found tackle so many forms. Here is a list of those forms, superficially described:

I admire the way the stories in Matt Bell’s How They Were Found tackle so many forms. Here is a list of those forms, superficially described: This second impulse is amplified when the book is confessional or obsessive or in some way different from other books you’ve read. Maggie Nelson’s Bluets is all three of those things. It’s a hybrid of essay and prose poem which starts as a meditation on the color blue, but ends up being about almost everything. If you look at a thing to which you’re drawn closely enough, the book seems to be saying, all your other important attachments will rise alongside the meditation about the thing you’ve taken as your subject.

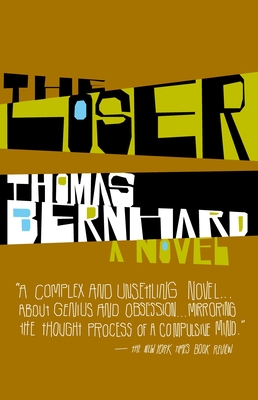

This second impulse is amplified when the book is confessional or obsessive or in some way different from other books you’ve read. Maggie Nelson’s Bluets is all three of those things. It’s a hybrid of essay and prose poem which starts as a meditation on the color blue, but ends up being about almost everything. If you look at a thing to which you’re drawn closely enough, the book seems to be saying, all your other important attachments will rise alongside the meditation about the thing you’ve taken as your subject. There have been several mini-posts on this site about Thomas Bernhard this week. One of our readers, Jonathan Callahan, pointed me toward an essay he wrote in the Collagist about Bernhard, Kafka, what he calls phrase-level and sentence-level virtuosity, reading in translation, and more. It’s an essay in the active Montaignian sense rather than the write-to-thesis sense. Probably someone here has linked to it before, but even if so, it deserves another look. Here’s an excerpt:

There have been several mini-posts on this site about Thomas Bernhard this week. One of our readers, Jonathan Callahan, pointed me toward an essay he wrote in the Collagist about Bernhard, Kafka, what he calls phrase-level and sentence-level virtuosity, reading in translation, and more. It’s an essay in the active Montaignian sense rather than the write-to-thesis sense. Probably someone here has linked to it before, but even if so, it deserves another look. Here’s an excerpt: In the opening pages of Thomas Bernhard’s

In the opening pages of Thomas Bernhard’s