Behind the Scenes

Ken Sparling’s The Serial Library: Overview and Interview

[Guest Post: Greg Gerke]

Ken Sparling is a writer. He works in a library in Toronto. He has written six novels. His latest is Intention, Implication, Wind from Pedlar Press. His first, Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall, published by Knopf in 1996 will be reissued by Mud Luscious Press in August.

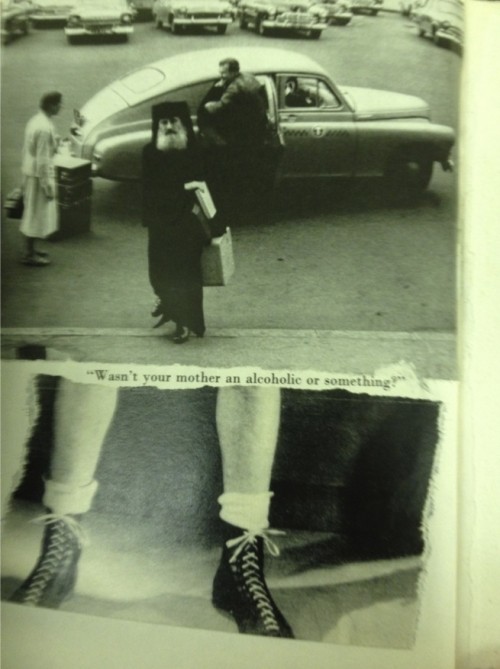

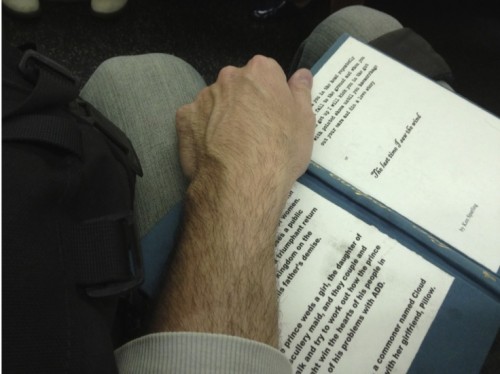

Not a stranger to making his books by hand (he handmade his second novel), his latest project, The Serial Library, involves taking old hardback books, ripping some pages out and pasting new test in along with old photographs and artwork. There are ten handmade books in The Serial Library and they are loaned out to people in such locations as Montreal, Calgary, Brooklyn, and Pennsylvania. The book I took out of The Serial Library was a one of kind—more than one of a kind. It was the only one—made from Dennis Cooper’s hardcover Try. The Last Time I Saw the Wind continues Sparling’s experimental narratives. There is a prince who likes to have affairs, but he eventually focuses on one woman. At the same time a first person narrator tells seemingly unrelated anecdotes from his life, including queries on love and touch, a portrait of a hot dog man, and such short fizzles as the following: “When I say I feel like I’ve been lucky, I mean to say that I didn’t get what I wanted out of life. Not ever. That was pretty lucky.”

Ken had this to say about the process:

There’s only going to be one of each book, but I’m going to keep making them. I’m treating this like performance, as opposed to composition. As in jazz, the performance is never the same as the original composition. So I have a manuscript that I was originally going to try to get into shape to submit to my publisher. That’s the composition. It’s about 100,000 words at the moment. Each performance involves selecting a book to deface, finding pictures, gluing them in, selecting text, revising and adding as I go (improvisation), formatting the text, then printing, ripping or cutting, then gluing. I select the pictures and text as I go, never jumping ahead more than a page or two. I also remove pages from the original book to keep the new book from getting too fat.

To maintain its essence as performance, the book has to change hands regularly; otherwise it just becomes another object on someone’s shelf. If it truly is a performance, then it can only realize its full potential in the hands of a new witness/reader. Thus the serial library.

I’ve slowed down in terms of making the books, but I do a bit of work almost every day. For sure I do a bit of writing every day, and often a bit of book construction. It’s very much improvisational, based on texture and rhythm and the music of the language, but also trying to see how much language can really say about anything, wondering about that. I’ve never felt so calm and unconcerned about anything I wrote. I think it’s because I know I’ll be making something new tomorrow and there’s no wall to run up against, no place where what I write turns to stone the way a manuscript eventually does when you funnel all your efforts toward making a book that will be mass produced.

***

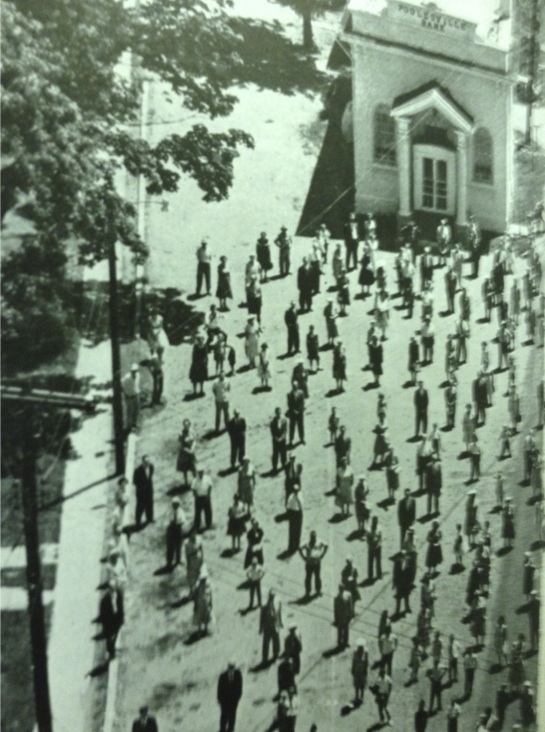

GG: Can you tell me about the images used. Where did you get them? In the book I read, I noticed many incredible shots, including stunning photos of groups of people taken from a bird’s eye view.

GG: Can you tell me about the images used. Where did you get them? In the book I read, I noticed many incredible shots, including stunning photos of groups of people taken from a bird’s eye view.

KEN: I get the images for the serial library books from magazines and books that I mostly buy in Book Ends, which is a bookstore at the library run by the Friends of the Library. They sell stuff pretty cheap. I like books of photography or fine art books with reproductions, and also old magazines if I can get them, like National Geographic or Life. It’s fun going up to the store every once in a while and browsing. I bought a lot of National Geographics from Book Ends a while back.

When I’m making the books, I pick the images that capture me. I seem to be drawn to black and white images, or nearly black and white images. I have a couple great old Life magazines with some images that I really love, but have yet to find a place in the books because the images in

Life are so big and I’m hesitant to crop them. I like to tear, not cut, the images out of books, but I’ll use scissors sometimes if it makes sense.

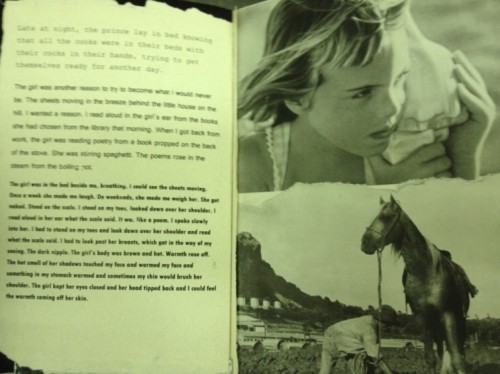

GG: There is a high degree of sensuality in the book The Last Time I Saw the Wind: “The hot smell of her shadows touched my face and warmed my face and something in my stomach warmed and sometimes my chin would brush her shoulder. The girl kept her eyes closed and her head tipped back and I could feel the warmth coming off her skin.”

This section is opposite a page with two photographs. In one, a small, pale blond haired child holds a sea-shell to her ear, and in the other a horse stands tall in the mud over a man who is bent before him. In the background is a mountain. Many things can be drawn from the interplay of text and image here. What, if anything, governs your choices in making the books?

KEN: Whatever governs my choices in creating the books is very visual, very intuitive. I select pictures I like, pictures that move me. The system has everything to do with the logistics of giving the pictures I am moved by a place that does them justice, visually, in the book. It comes down to finding a space that can accommodate them…even just in terms of the size of the pictures, or how much I can get away with cropping without diminishing the power of the image. I love finding an image that has another image on the back and I can use both images in the book. Or coming across a blank page in the book (between chapters, or whatever) that I can utilize somehow.

I don’t ever select a picture based on text on a facing page. Although I’ll often place the blank back of a text page next to an image where I want the image to stand alone, with no text opposite it.

GG: I’ve read a number of your books and a most have a fragmented narrative. A story will begin and then another story will start, then another. Sometimes you come back to these stories, sometimes not. What draws you to this style of writing?

GG: I’ve read a number of your books and a most have a fragmented narrative. A story will begin and then another story will start, then another. Sometimes you come back to these stories, sometimes not. What draws you to this style of writing?

KEN: Do you know Brad Mahldau, the pianist? I just read an essay he wrote about the balance between composition and improvisation, and in it he talks about the compositions of Thelonious Monk, saying: “Indeed, we almost need another name than melody here; it is more like the remaining broken shards of a melody that once existed.”

You talk about a fragmented narrative in my writing, but I’d like to think of another name than narrative here. Maybe what you call a fragmented narrative is less a series of broken narrative shards, more a kind of straining toward narrative, in the same way we strain to make of our lives a thread that leads us somewhere we like to imagine ourselves eventually arriving.

A jazz tune generally starts with a composed melody, the head, and then the players riff over the harmonic structure that underlies the head. There’s no composed head in the serial library books. But I hope the writing in the serial library books seems to refer to a kind of structure that you could understand in terms of narrative. That underlying structure might just be my life up to now, or my writing up to the brink of the serial library. So that now my writing has become one unbroken improvisation, and each book in the serial library is a continuation of my improvising on the same tune I’ve been improvising on all along. The fact that there are a bunch of discrete entities in the serial library is akin to the fact that the day comes to an end. Yes, each book in the serial library is a fixed entity enclosed in a cover, so it seems that each of the books comes to an end, but from my perspective, there’s no break, no beginning, no end, I just keep carrying on with the improvisation, which is why, I think, this is turning out to be so supremely satisfying. I’m not thinking in terms of a project, or any kind of end. There is just this ongoing improvisation using language that I do each morning for ten or twenty minutes, and on the weekends for a little longer sometimes, and sometimes after work (but mostly I’m just too exhausted at the end of the day) or in the middle of the night when I can’t sleep, which is more nights than not these days.

Here’s something else Mahldau says: “Monk was onto something else, though, and it involves the actual development of themes during his solo. By development, I mean that the musical content unfolds with a narrative logic; each idea springs from the previous one… The way in which this organic development continues during Monk’s solo suggests that when a song has a deeply embedded architecture like that of “I Mean You,” it will lend itself to formally richer solos, but only if the soloist is aware of the architecture and wishes to comment on it.”

With literature, maybe you could think of the reader as the soloist. To the extent that the reader is aware of the architecture of what I’m doing and wishes to comment on it, that reader will have a richer reading experience, the way a soloist will have a richer experience if he understands what Monk was doing and has a hunger to comment or respond.

“Monk set the bar for an approach to improvisation in which form itself becomes an expressive means.”

The form I’ve chosen, this straining toward narrative, I hope will become for the reader an expressive means that underlies and complements the content of what I write.

Tags: greg gerke, interview, Ken Sparling

Isn’t that what “one of a kind” means?

“One of a kind” means unique. It doesn’t mean it’s the only one in existence, as each of Ken’s books are.

It’s “unique” that fairly strongly connotes ‘only one in existence’. I thought that you were playing with the secondary, hyperbole-diluted use of “one of a kind” – which also means ‘only one in existence’, literally, but often is used to mean the less uncommon ‘very cool’ – , by saying that Sparling’s books are, as it were, extra unique.

When someone qualifies “unique” as though it were a gradable modifier, it leaps out (at me, anyway). Your “more than one of a kind” seems clearly to be play. I’d thought Michael was making a (self-deprecating) joke about pedantry. ?

Sparling’s books sound cool, and “straining toward narrative” is very interesting. I’d add that Monk’s “embedded architecture” makes of narrative a matter of co-discovery as much as authorial imposition, of the player imposing the player’s discovery (which, to me, is what “jazz” is, with respect to, say, melody).

[…] :: Ken Sparlings, “The Serial Library,” a performance image-text project. […]