Random

“Surely no reader will wish me to invent anything further” : On B.S. Johnson’s Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry

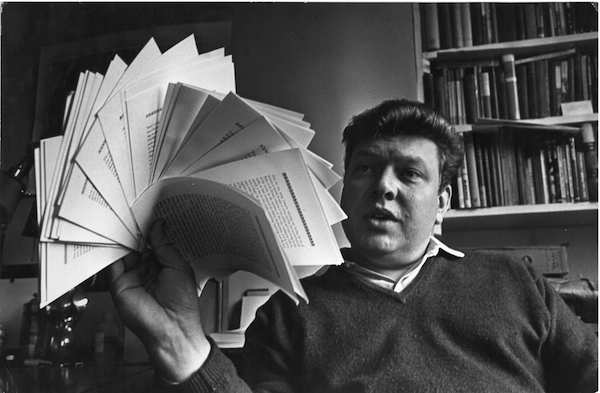

I’m not sure you could come up with a better name for an experimental writer than B.S. Johnson: it sounds like someone both regal and a joke, which for the English writer of this name, who walked a strange line between outsider artist and one at the cusp of avant-garde, it could hardly be more fitting. B.S. Johnson was decades ahead of his own time, both in the fuck-all way he approached the act of narrative, and the very outline of his life. His was a career that would not begin to find its traction until long after his death, and for my money, still not to the level he deserves.

From the beginning, it was clear that Johnson wanted little to do with the bullshit tropes of how a book is known to work. Raised by a working class family and spending his early years working as a bank clerk, he eventually taught himself Latin and left the workforce for college, then began writing as an assault on what he critically referred to as the “neo-Dickensian” output of those who would become his literary peers.

His first novel, Traveling People (1963), which he eventually disavowed, established what would become an ongoing attempt to disrupt the natural flow of any plot by continuously switching out narrative devices; from direct first person description to screenplay-like dialogue to personal journal entries to stream-of-consciousness, and so on. The would-be fictional “dream” remains continuously disrupted by the voice of the author himself, breaking the third wall to explain how even these continuously varying storytelling methods are nothing but distractions, made of deceits.

Throughout all of his work, Johnson would continue to belittle any semblance of linearity, taking further and further lengths to obscure all traditional aim. His second novel, Albert Angelo (1964), famously featured holes cut through its pages both to distract the reader’s eye and to dash any suspension of disbelief, eventually even breaking down to give up on the formalities entirely; “fuck all this lying,” he writes, “look what im really trying to write about is writing…Im trying to say something not tell a story telling stories is telling lies and I want to tell the truth.” His fourth novel, The Unfortunates (1969), would be published in a box, containing a bunch of loose pages, leaving the reader to figure out how to read them. No matter what, with Johnson there could be no pretending that what was happening between writer and reader was a game, if one with serious consequences at stake, so much so that Johnson would often seem to be by turns upset at his own characters, their voices, their desires, and most emphatically, the act of writing itself.

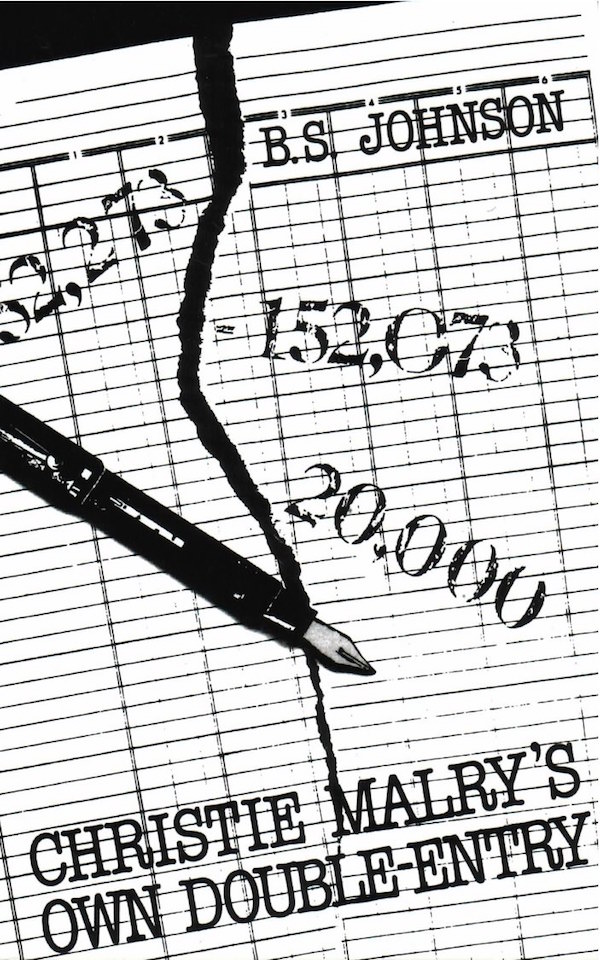

At the heart of that rebellion, though, as I read it, is a burning desire for reconfiguration, for something more than pretense made of words. Such feeling could not be more vehemently rendered than in Johnson’s penultimate work, Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry (1973). The novel tells the story, or at least pretends to, of the eighteen-year-old title character, who like Johnson had, takes work at a bank—“to place himself next to the money, or at least next to those who were making it.” He quickly finds, though—within the first three pages—that neither money nor being around it makes him happy: “This atmosphere was acrid with frustration, boredom and jealousy, black with acrimony, pettiness and bureaucracy.” Young Malry finds the act of living “hard to take, hard to live,” half having given up as a teenager already looking “forward to his eightieth birthday.” Even Malry’s own mother, before she ups and dies for no good reason on page thirty, tells Malry she has only been his mother “for the purposes of this novel,” warning him with her last breath that: “Even if we understand that all is chaos, the understanding itself represents a denial of chaos, and must therefore be an illusion.”

From out of this disconnection, the lack of direction, the actual battery of the novel begins to thrive. Malry begins keeping a ledger of ways that life has done him wrong, to be counteracted by him against the world in direct action. For each negative human experience, however petty—including “Unpleasantness of Bank General Manager” and “Chagrin at learning no secrets”—he then offsets the trade by means such as, at first, leaving his bills unpaid, or making a scratch along a public wall to ruin it. What he cannot pay back at once is carried over, resulting in a tabulation of karmic debt he carries on, laid out in actual ledger notation inserted into the book’s pages amidst Malry’s increasingly schizophrenic-seeming interactions. And as the debt continues to accrue, Malry will begin to take more and more harsh methods of repayment, toward something like horror.

It’s an insane set up for a book, for sure, and one that in Johnson’s intentionally meandering narration at first seems outlandish, even amateurish. But it’s that very feeling that becomes mesmerizing in its method as the weight continues to accrue. What begins as an almost arbitrary impetus for defining a character’s fictional existence, an almost arbitrary whim of a plot, eventually becomes macabre and deconstructive in a manner more contemporary than most books manage to become, carried forward by Johnson’s continuously irreverent and improvisational manners of description and interruption, not to mention his fantastically black sense of humor and fragmentary finesse, such that as Malry’s sense of reality continues to splinter, his acts grow more desperate, more brutal, threatening the very firmament of the world of the book itself. Walls between author and character, the reader’s world and the invented world, become further and further dashed, eventually falling into direct address of the contemporary quandary of fiction.

“Surely no reader will wish me to invent anything further,” Johnson tells Malry directly, amid a state of where the plot has all but been abandoned beyond dissection of the nature of the book itself. “Surely he or she can extrapolate only too easily from what has gone before.” Malry, the fictional character, offers no solace for his creator: “If there is a reader,” he replies. “Most people won’t read it.”

Like Jodorowsky’s meta-closing to The Holy Mountain, in which he tells the viewer to leave and go back to real life, Johnson’s destruction of the book beneath its own feet is freeing, exciting. Its frankness might make the reader only want to believe everything the book has made up already even more, no longer forced to include ourselves in a transaction where we must pretend we’ve gotten somewhere in following a false person around along the page, instead for once subjecting the reader to a voice interested in exploring its own limits and intents. Johnson’s aspiration begins less to seem want to destroy fiction, but to unleash it; to give up the horseshit and find something more, something that continues after the book is closed and the story’s over.

Despite his desires, though, Johnson’s work would fail to save him. As his irregular practices continued and expanded into film work, alienating publishers and peers alike along the way, Johnson’s inability to connect to an audience the way he wanted led him into depression, one only further aggravated by family trouble and alcohol. At age forty, he cut his life short by slitting his wrists, leaving in his wake a vibrant body of work that continues to this day to wield its as yet unanswerable questions.

Tags: b.s. johnson, christie malry's own double entry