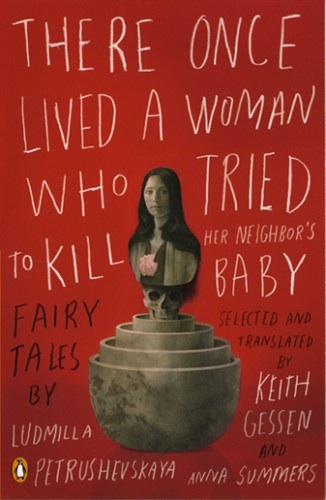

There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, translated from the Russian by Keith Gessen and Anna Summers. pp. 206, $15 list ($10.50 at the above-linked Powells page)

There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, translated from the Russian by Keith Gessen and Anna Summers. pp. 206, $15 list ($10.50 at the above-linked Powells page)

.

YOU THINK YOU HAVE IT HARD

by Eva Talmadge

.

Sometimes I steal books from Justin. It happens. Last week I swiped a good one: Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby, selected and translated by Keith Gessen and Anna Summers. If Justin ever catches on and tries to steal his book back, I’ll go out and buy it, and then read it all again—because this funny, strange, and gruesome short collection is well worth paying full retail ($15) for.

But I don’t want to write one of those reviews that reads like a press release or a protracted blurb. Petrushevskaya is a master storyteller, and like all good fairy tales, hers end in tears. You already know that. Just look at the cover. And it’s easy to say Petrushevskaya is the “heir to the spellbinding tradition of Gogol and Poe”—it says so right there on the back of the book. So okay. Any decent batch of gothic and supernatural short stories is going to get a Poe comp, and Americans will give just about any fiction translated from Russian a Gogol mention. Those are two writers whose names sell books, and pretty much no-brainers here, but (here’s where it gets blurby) damned if Petrushevskaya doesn’t live up to those comparisons and then some, matching both in inventiveness and in gore—and perhaps beating them in heart.

“Incident at Sokolniki,” a ghost story that would do Poe proud, opens straightforwardly enough: “Early in the war in Moscow there lived a woman named Lida. Her husband was a pilot, and she didn’t love him very much, but they got along well enough.” Petrushevskaya plays a classic gothic trick, and the story ends in an act of tenderness (a kind of duty, if not love) that echoes throughout this book: hardships are plenty and survival—not happiness—is the point of life. But even in a warzone there is room for kindness. In “Hygiene,” a young girl and a cat survive a plague that ravages their city. Again the tenderness is hidden behind a portrait of an unhappy home: “Nikolai ate a great deal. He ate so much the grandfather felt compelled to make a remark. Elena came to her husband’s defense, and then the little girl asked why everyone was arguing, and family life went on its way.” The plague that follows spares only those who take care of one another—a stranger, the little girl, her cat—while the rest die fending for themselves.

And let’s not forget Gogol. A nod to “The Nose” ends one of the grimmest stories in this collection, “The Miracle.” Just as things couldn’t possibly get worse for Nadya, whose son has stolen her life savings and whose only hope, Uncle Kornil, has fallen over dead, everything is “suddenly enshrouded in fog.” But here’s the thing: the Poe and Gogol labels really don’t do Petrushevskaya justice. In the century-and-a-half since those writers’ deaths (both would have turned 200 last year), a lot of shit has gone down: two world wars killed 25 million people in Russia alone, some 14.5 million died in Stalin’s de-kulakization and famine in neighboring Ukraine, and another 12 million were killed or imprisoned in gulags with 10% survival rates in the purge that followed. (These figures come from Wikipedia and Robert Conquest, and we aren’t even counting other massive disasters—the Russian Revolution and Civil War, two other famines, plus everyone who died post-Stalin or killed themselves after reading Conquest’s books.)

So what does all that history do to fiction? How can anyone dare to write after that kind of horror? Petrushevskaya’s answers that question by taking one of the oldest story forms—the fairy tale—and recasting it for the post-disaster world. We process our experiences, especially the bad ones, by telling ourselves stories: “it happened like this,” or “it happened for this reason,” or “it really did not happen at all.” So each narrative helps carry the weight. Petrushevskaya’s characters walk around under it—whether it’s her personal history, or Russia’s—in purgatory, widowed or suicidal or orphaned or so lonely they’ll take in any baby that turns up, scraping the meagerest of existences out of the miserable earth. Wearing one of Gogol’s shabby overcoats or chasing after a severed nose wouldn’t even rate as minor problems for her people.

That’s not to say her stories are uniformly depressing—there’s plenty of gallows humor here, and moments of cheerfulness that mark the truly desperate. And sometimes things turn out okay: the relatively well-off mother-daughter of “There’s Someone in the House” (my stand-out favorite) throws away her clothes to outsmart a poltergeist, casting off the weight of a lifetime’s worth of abuse. And even in the bleakest settings, as in “The New Robinson Crusoes: A Chronicle of the End of the Twentieth Century” (if you only read one story, make it this one), the characters may be without hope but the prose is pure, consoling art:

“If in fact we’re not alone, then they’ll come for us. That much is clear. But, first of all, my father has a rifle, and we have skis and a smart dog. Second of all, they won’t come for a while yet. We’re living and waiting, and out there, we know, someone is also living, and waiting, until our grain grows and our bread grows, and out potatoes, and our new goats—and that’s when they’ll come.”

Tags: Anna Summers, eva talmadge, Keith Gessen, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

Nice post. I want to buy this now.

Nice post. I want to buy this now.

Yes, Petruschevskaya is worth reading. She literally fleshed out (if not invented) the phenomenon of chernukha” in Russian literature: a symbiosis of everyday style with dark themes, so the prosaicness of life becomes bizarr and surreal. And this surreality is the reflection of life you recognize in the textes of Petruschevskaya.

Sure, Dostoyevsky was also one of the greatest masters of Russian “chernukha”, just his historical distance to our days makes him classical reading. Petrushevskaya is documentary of modern insanity.

And reading here can be best represented by the painting by Magritte “La Lectrice Soumise”

http://imagecache2.allposters.com/images/pic/RET/rrdg0163~La-Lectrice-Soumise-Posters.jpg

Yes, Petruschevskaya is worth reading. She literally fleshed out (if not invented) the phenomenon of chernukha” in Russian literature: a symbiosis of everyday style with dark themes, so the prosaicness of life becomes bizarr and surreal. And this surreality is the reflection of life you recognize in the textes of Petruschevskaya.

Sure, Dostoyevsky was also one of the greatest masters of Russian “chernukha”, just his historical distance to our days makes him classical reading. Petrushevskaya is documentary of modern insanity.

And reading here can be best represented by the painting by Magritte “La Lectrice Soumise”

http://imagecache2.allposters.com/images/pic/RET/rrdg0163~La-Lectrice-Soumise-Posters.jpg

Went directly to NYPL.org and placed an interlibrary request!

This is my favorite thing about HTMLGIANT; finding out about books and then hopping over to the library website and placing a hold.

Went directly to NYPL.org and placed an interlibrary request!

This is my favorite thing about HTMLGIANT; finding out about books and then hopping over to the library website and placing a hold.

man, this looks great – going to track this down – thanks eva

man, this looks great – going to track this down – thanks eva

buying this.

buying this.

[…] HTMLGIANT / Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s Scary Fairy Tales […]

I read this a few months ago and two stories still stick out: the plague story, as well as the siamese twins one. I definitely want to reread it again at some point to give the other stories a chance, but the aforementioned tales were haunting. I guess fitting, eh?

I read this a few months ago and two stories still stick out: the plague story, as well as the siamese twins one. I definitely want to reread it again at some point to give the other stories a chance, but the aforementioned tales were haunting. I guess fitting, eh?

Also, I love this feature. I think we could use more guest reviews or just reviews of books on the site. Nothing crazy, but maybe one or two a week would be cool. It’s always cool to find out about new books from this site, but it doesn’t happen that much. I’m still grateful about “About A Mountain” and feel that there are a lot of books out there that individuals on this site could share with the community.

Also, I love this feature. I think we could use more guest reviews or just reviews of books on the site. Nothing crazy, but maybe one or two a week would be cool. It’s always cool to find out about new books from this site, but it doesn’t happen that much. I’m still grateful about “About A Mountain” and feel that there are a lot of books out there that individuals on this site could share with the community.

new face of the site coming very soon. i think you will find your request fulfilled. thanks Neil.

new face of the site coming very soon. i think you will find your request fulfilled. thanks Neil.

Always happy to write more reviews! Especially when the comments threads are as friendly and appreciative as this one. (Of course, Petrushevskaya is an easy writer to love.)

Always happy to write more reviews! Especially when the comments threads are as friendly and appreciative as this one. (Of course, Petrushevskaya is an easy writer to love.)

“But I don’t want to write one of those reviews that reads like a press release or a protracted blurb.”

Wow, if your colleagues followed this dictum The Gint would disappear! Poof. The story that birthed the book’s title is free via the NPR: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=120989593

“But I don’t want to write one of those reviews that reads like a press release or a protracted blurb.”

Wow, if your colleagues followed this dictum The Gint would disappear! Poof. The story that birthed the book’s title is free via the NPR: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=120989593