I am drinking Juicy Juice and scouring the Internet for action figures based on my favorite childhood comics & cartoon franchises while complaining about—nay, BEMOANING—capitalism’s failure to deliver to me precisely what I want

Four or five years ago, for my birthday, I bought myself Neca’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles figures—the awesome ones based on the original Kevin Eastman & Peter Laird’s original comics, like so:

They are so utterly badass. They all have red bandanas, for one thing, and they also have tails, which got clipped from the later TV cartoon versions because they looked like—penises, I guess.

As you can readily see, I am a proud owner of these figures:

Reading Frank Miller’s influences on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy

One more post on the Batman, if you’ll please. It’s no secret that Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy drew a lot of inspiration from Frank Miller—specifically, from his 1986 mini-series Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and its 1987 follow-up, Year One (which featured art by David Mazzucchelli). And so I felt like taking some time to note all the connections (or at least the ones I can see—feel free to chime in as to what I’ve missed!).

I’ve already commented elsewhere on how Batman Begins took:

- the Tumbler design (The Dark Knight Returns);

- Batman’s escape from the police by means of a bat homing device (Year One);

- and the ending in which Commissioner Gordon muses about the arrival of the Joker, having received one of his calling cards (Year One).

And there are still more connections. Commissioner Gordon’s character arc in that film is similar to the one he follows in Year One—he even has a corrupt partner named Flass. Furthermore, Bruce Wayne distances himself from the Batman by cultivating the image of a drunken playboy:

That’s everything that I can see in the first film.

The Dark Knight is I think the least indebted to Miller of the three films. Nonetheless, its ending, wherein Two-Face kidnaps Gordon’s family, echoes the mob’s kidnapping of Gordon’s family at the conclusion of Year One—Batman even saves Gordon’s son from falling:

Moving on to the The Dark Knight Rises …

We Need to Talk About Batman

I want to argue that the conceit of Batman having a secret identity no longer works.

It once did, back in the 1930s and ’40s, when Batman was essentially a badass moonlighting in tights, socking hoodlums and thugs in their jaws. At that time, the extent of the audience’s suspension of disbelief was that the fellow wouldn’t get shot.

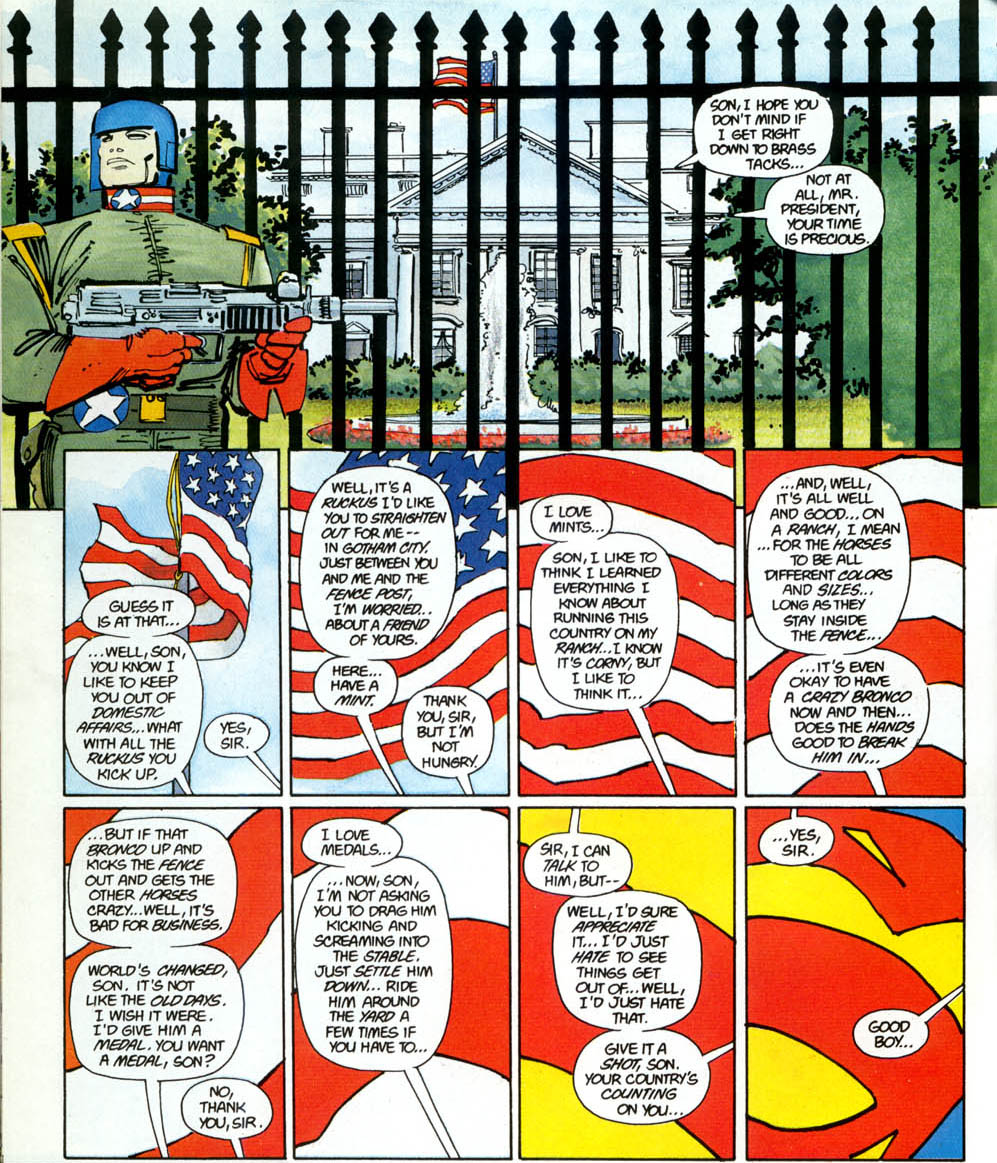

How simple, compared to today. The Batman of 2012 is a one-man paramilitary force capable of investing hundreds of millions of dollars into being the Caped Crusader—a one-man Blackwater USA! Frank Miller was right: there’s no way that the U.S. government would permit this guy to exist:

The Ever Risable Dark Knight

In the set piece that opens The Dark Knight Rises, a CIA operative screams at three hooded captives, “The flight plan I just filed with the Agency lists me, my men, Dr. Pavel here, but only one—of you!” He then starts pretending to toss them out of his airplane, only to be interrupted by the masked terrorist Bane, who has seen through his deceit (“Perhaps he’s wondering why someone would shoot a man … before throwing him out of a plane!”). Menacing banter ensues, after which Bane gains control of the aircraft and prepares to crash it. Grabbing Dr. Pavel, he commands an underling to remain on board, because “they expect one of us in the wreckage, brother!”

This is the kind of exchange Christopher Nolan thinks clever, when really it makes no sense. The plane was riddled with bullets, its wings torn away, its tail end blown off by explosives. Obviously somebody attacked it—so who cares if the bodies in the wreckage match the flight plan? What’s more, the CIA man wasn’t telling the truth about throwing them out—Bane even commented on that—so why trust his line about the flight plan?

These might seem like nitpicking, geeky griping over plot holes. But this exchange illustrates so much of what’s so wrong with Nolan’s movies.

For one thing, his characters never shut up.

Viktor Shklovsky wants to make you a better writer, part 1: device & defamiliarization

When I was finishing up my Master’s degree at ISU, I worried that I still didn’t know much about writing—like, how to actually do it. My mentor Curtis White told me, “Just read Viktor Shklovsky; it’s all in there.” So I moved to Thailand and spent the next two years poring over Theory of Prose. When I returned to the US in the summer of 2005, I sat down and started really writing.

I’ve already put up one post about what, specifically I learned from Theory of Prose, but it occurs to me now that I can be even more specific. So this will be the first in a series of posts in which I try to boil ToP down into a kind of “notes on craft,” as well as reiterate some of the more theoretical arguments that I’ve been making both here and at Big Other over the past 2+ years. Of course if this interests you, then I most fervently recommend that you actually read the Shklovsky—and not just ToP but his other critical texts as well as his fiction, which is marvelous. (Indeed, Curt has since told me that he didn’t mean for me to focus so much on ToP! But I still find it extraordinarily useful.)

Let’s talk first about where Viktor Shklovsky himself started: the concepts of device and defamiliarization.

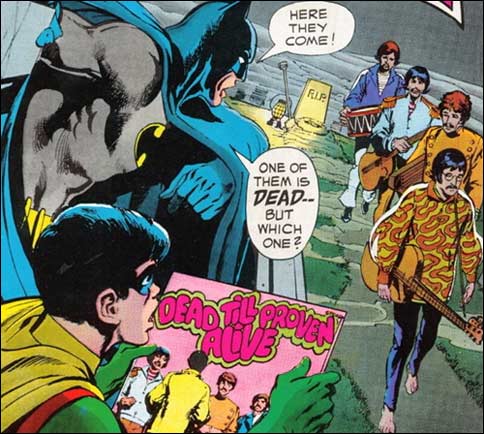

Another way to generate text #2: “backmasking” (now with bonus Batman/Beatles content)

As I mentioned in my last post (“The Spell Check Technique”), I’ve played around with more than a few means for generating text. Another one that I used when writing Giant Slugs is a trick that I somewhat jokingly called “backmasking.” Here’s how it works:

- Write a sentence or the start of a sentence.

Something Film Understands but that Literature Doesn’t

I was talking with Jeremy M. Davies recently (actually, we were on our way to see Drive), and the topic of genre as art came up. Now, Jeremy and I are both huge into genre, in all media. We’re nuts over spy thrillers, sci-fi, and fantasy, for instance—not to mention Batman comics. (Only the good ones, though, natch.)

And of course lots of people in various lit scenes (all over) don’t think that genre fiction can be art. They’re really wedded to that “high art / low art” divide. (Or the “literary fiction / all else” divide, as it’s so commonly called.)

Me and J, we were saying how we don’t get it. How can someone read, for instance, Patricia Highsmith’s Ripliad and not recognize it as total artistic brilliance? Or Philip K. Dick’s VALIS, which is one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, hands down? And of course I’d argue that Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns is one of the finest things published in the 1980s, “despite its being” a comic book. (I didn’t spend all that time analyzing it at Big Other because I thought it was merely cute.)

Anyway, I came to a certain conclusion…

A Critique of Jim Emerson’s Recent “The Dark Knight” Critique

You’ve probably seen by now film critic Jim Emerson‘s critique of a certain action sequence in The Dark Knight (2008). Many, many people forwarded it to me; they probably also forwarded it to you.

Now, I have said many mean things about Mr. Nolan in the past. But I actually disagree to some extent with Mr. Emerson’s analysis. (Maybe I just disagree with everyone?)

So allow me, if you will, to defend my buddy Chris Nolan.