Reading Frank Miller’s influences on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy

One more post on the Batman, if you’ll please. It’s no secret that Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy drew a lot of inspiration from Frank Miller—specifically, from his 1986 mini-series Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and its 1987 follow-up, Year One (which featured art by David Mazzucchelli). And so I felt like taking some time to note all the connections (or at least the ones I can see—feel free to chime in as to what I’ve missed!).

I’ve already commented elsewhere on how Batman Begins took:

- the Tumbler design (The Dark Knight Returns);

- Batman’s escape from the police by means of a bat homing device (Year One);

- and the ending in which Commissioner Gordon muses about the arrival of the Joker, having received one of his calling cards (Year One).

And there are still more connections. Commissioner Gordon’s character arc in that film is similar to the one he follows in Year One—he even has a corrupt partner named Flass. Furthermore, Bruce Wayne distances himself from the Batman by cultivating the image of a drunken playboy:

That’s everything that I can see in the first film.

The Dark Knight is I think the least indebted to Miller of the three films. Nonetheless, its ending, wherein Two-Face kidnaps Gordon’s family, echoes the mob’s kidnapping of Gordon’s family at the conclusion of Year One—Batman even saves Gordon’s son from falling:

Moving on to the The Dark Knight Rises …

We Need to Talk About Batman

I want to argue that the conceit of Batman having a secret identity no longer works.

It once did, back in the 1930s and ’40s, when Batman was essentially a badass moonlighting in tights, socking hoodlums and thugs in their jaws. At that time, the extent of the audience’s suspension of disbelief was that the fellow wouldn’t get shot.

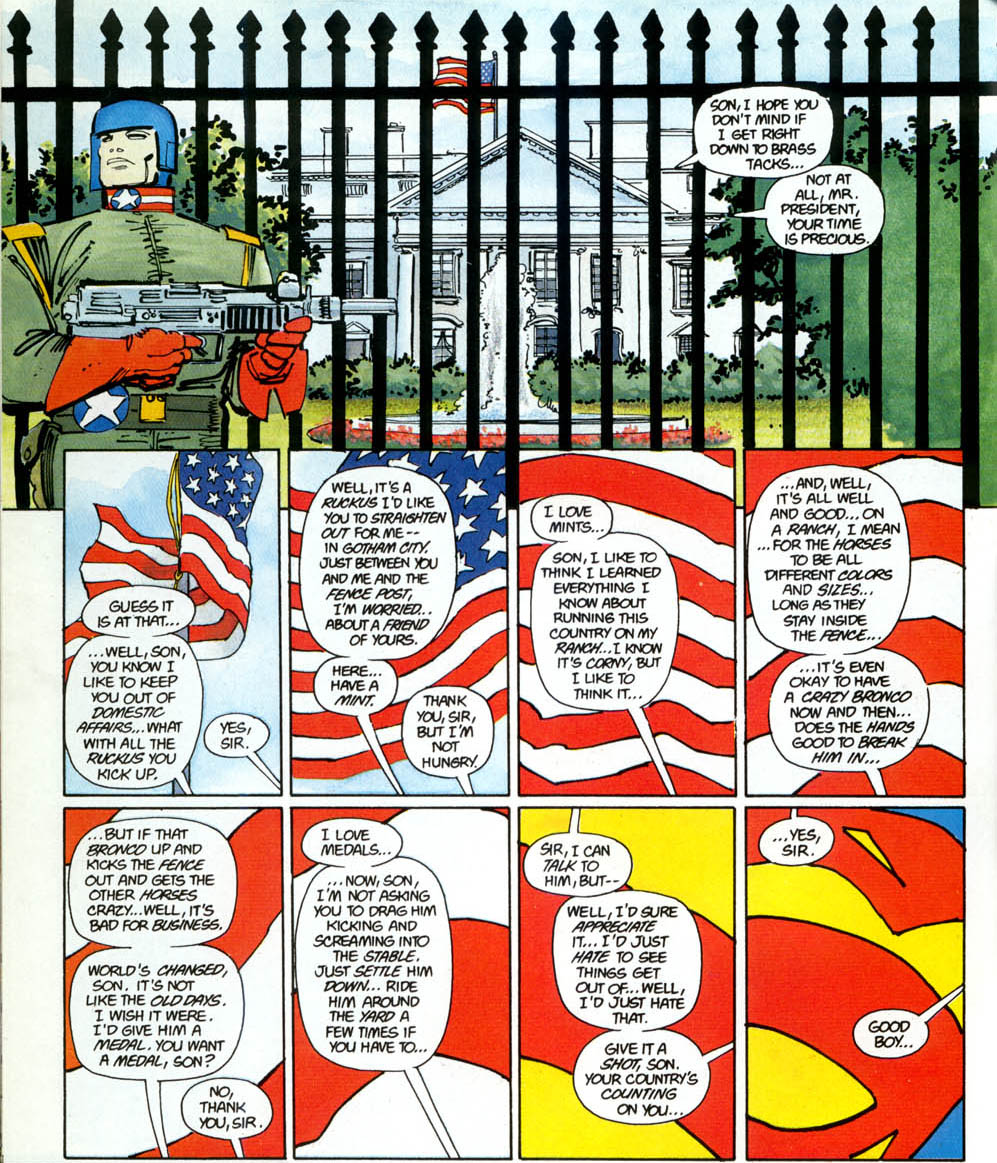

How simple, compared to today. The Batman of 2012 is a one-man paramilitary force capable of investing hundreds of millions of dollars into being the Caped Crusader—a one-man Blackwater USA! Frank Miller was right: there’s no way that the U.S. government would permit this guy to exist:

The Ever Risable Dark Knight

In the set piece that opens The Dark Knight Rises, a CIA operative screams at three hooded captives, “The flight plan I just filed with the Agency lists me, my men, Dr. Pavel here, but only one—of you!” He then starts pretending to toss them out of his airplane, only to be interrupted by the masked terrorist Bane, who has seen through his deceit (“Perhaps he’s wondering why someone would shoot a man … before throwing him out of a plane!”). Menacing banter ensues, after which Bane gains control of the aircraft and prepares to crash it. Grabbing Dr. Pavel, he commands an underling to remain on board, because “they expect one of us in the wreckage, brother!”

This is the kind of exchange Christopher Nolan thinks clever, when really it makes no sense. The plane was riddled with bullets, its wings torn away, its tail end blown off by explosives. Obviously somebody attacked it—so who cares if the bodies in the wreckage match the flight plan? What’s more, the CIA man wasn’t telling the truth about throwing them out—Bane even commented on that—so why trust his line about the flight plan?

These might seem like nitpicking, geeky griping over plot holes. But this exchange illustrates so much of what’s so wrong with Nolan’s movies.

For one thing, his characters never shut up.

Viktor Shklovsky wants to make you a better writer, part 1: device & defamiliarization

When I was finishing up my Master’s degree at ISU, I worried that I still didn’t know much about writing—like, how to actually do it. My mentor Curtis White told me, “Just read Viktor Shklovsky; it’s all in there.” So I moved to Thailand and spent the next two years poring over Theory of Prose. When I returned to the US in the summer of 2005, I sat down and started really writing.

I’ve already put up one post about what, specifically I learned from Theory of Prose, but it occurs to me now that I can be even more specific. So this will be the first in a series of posts in which I try to boil ToP down into a kind of “notes on craft,” as well as reiterate some of the more theoretical arguments that I’ve been making both here and at Big Other over the past 2+ years. Of course if this interests you, then I most fervently recommend that you actually read the Shklovsky—and not just ToP but his other critical texts as well as his fiction, which is marvelous. (Indeed, Curt has since told me that he didn’t mean for me to focus so much on ToP! But I still find it extraordinarily useful.)

Let’s talk first about where Viktor Shklovsky himself started: the concepts of device and defamiliarization.

I made a video that critiques the opening three scenes of “Inception”

I’m trying out different ways of doing film criticism. In addition to writing articles, I think it makes sense to record commentaries (like the one I just did for Drive) and make critical videos. (My inspirations here are Mike Stoklasa and Jim Emerson.)

So here’s my own foray into the latter:

I recorded a commentary track for “Drive”

Hey, HTMLGiant. I recorded a commentary track for Drive; you can download it here. It’s an mp3, 42 MB, 104 minutes long.

Of course I made it so brilliant that you can just listen to it on its own. But if you watch it with Drive (recommended!), it’s all synced up, so cue it to start when the Universal logo starts.

Related posts:

- “DRIVE”

- “Let’s watch a scene from Drive and analyze it”

- “Cliché as Necessity (Birthing Innovation)”

- “Something Film Understands but that Literature Doesn’t”

- “A Little Bit More on Cliché”

Next, I’ll record commentary for Inception.

And Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.

And The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

And Southland Tales.

Update: I forgot to include a link to Scorpio Rising. Here’s a clip:

And here’s the full film.

A Critique of Jim Emerson’s Recent “The Dark Knight” Critique

You’ve probably seen by now film critic Jim Emerson‘s critique of a certain action sequence in The Dark Knight (2008). Many, many people forwarded it to me; they probably also forwarded it to you.

Now, I have said many mean things about Mr. Nolan in the past. But I actually disagree to some extent with Mr. Emerson’s analysis. (Maybe I just disagree with everyone?)

So allow me, if you will, to defend my buddy Chris Nolan.