Author Spotlight

My fear arouses me: an interview with Dennis Cooper

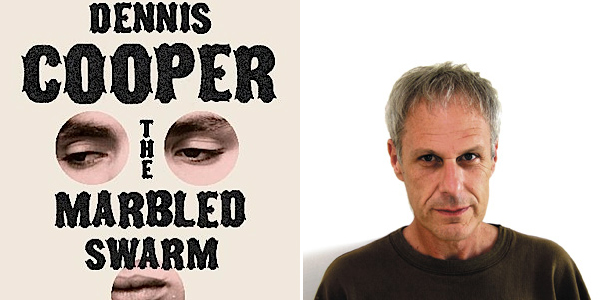

The odds are decent that you know Dennis Cooper better than I do. After hearing about his work for years and constantly promising myself that I would try a little someday, I found myself graduated from the MFA program with time to read books of my own choosing again, and so I finally started reading his novels, and I haven’t stopped in the few months since. You’ve already read in this space about his latest book, The Marbled Swarm, a ludicrously powerful book that you really need. After reading The Marbled Swarm I had to send him some painfully earnest fan mail, and he received this note with a grace and generosity that will surprise no one who has read his blog. I asked if I could interview him. He said yes. His answers are more than worth your time; the book demands it.

So I had a really frustrating experience buying The Marbled Swarm at a local independent bookstore. I saw that they had two copies of Blake Butler’s There Is No Year shelved where you would expect, and I figured it would be easy from there because a) you share a press and b) “Butler” is alphabetically pretty close to “Cooper.” After a long search, I had to go ask one of the bookstore employees. She said that your book was supposed to be shelved in gay fiction, with a question mark at the end of her statement. (I was there with my wife; the employee seemed skeptical that I would want a book from the gay fiction section. I was sort of furious about that whole interaction.) And it was there! Do you like being shelved under the category of gay fiction? Do you think it’s been helpful for your work, commercially or otherwise?

I’m always surprised and disappointed when my books are cordoned off like that. I can’t speak to the reasons why that store in particular shelved The Marbled Swarm there, obviously, but, in general, I think it’s the result of a longstanding habit.

When I published my first couple of novels in the late 80s and early 90s, there was this vogue among critics and publishers regarding the notion of ‘gay literature’. I think that was the point where literary arbiters first cottoned onto the idea that there was a historical trajectory involving the work of authors who happened to be gay that had been largely unexplored and was ripe for a thinkfest. Also, there was apparently a decent sized gay male readership of fiction at that time. I remember people in the publishing industry saying that any gay-themed novel was pretty much guaranteed to sell around 5000 copies, so quite a number of writers who happened to be gay were being swept up by major publishers and given small advances based on the logic that the books would at least earn back if not even make everyone involved a bit of money. I’m not sure if that was actually true or not.

I think the fact that my work passed for gay fiction helped get me onboard, and I did receive one of those aforementioned small advances ($2000) for my first novel Closer, although I think my luck there had just as much to do with my work fitting neatly into the historical tastes and profile of Grove Press, who, at that time, were still flying the edgy avant-garde flag by publishing Kathy Acker, Robbe-Grillet, Gary Indiana, and others. In any case, for years Grove put the keyword ‘gay fiction’ prominently in those little lists that publishers imprint on book covers and in catalogs to tell bookstores and libraries and I guess even readers what to expect. So, that caused my books to be sequestered initially, and I’m guessing that some bookstores just assume my name is still another word for gay.

So, I think the gay tag likely did help a very uncommercial writer like myself instigate an unlikely foothold in the so-called major publishing world, but, at this point, given that my readership is really mixed and that I’ve never considered my work to be gay or about gay identity or specific in that way at all, I find the categorization more lazy and restrictive than anything else.

You’ve said in other interviews that you were positioned by others as a “bad boy” more or less from the beginning of your career. And it’s easy to see how that would happen. You write consistently about brutal stuff. You’ve always said, though, that the idea is not to be evil, not to shock. And yet interviewers never seem to ask the natural followup question: what is the goal?

Well, to me, the whole argument that writing about sex and violence and the more extreme effects of confusion and etc. in a direct way automatically makes one a ‘bad boy’ is kind of crazed. I see the things I write about as hugely central and emotionally/psychologically deep and representative of not uncommon fantasies and/or actions. I don’t see that writing explicitly about brutality is tantamount to jamming it down people’s throats. I see my approach as being fair and appropriately subservient to the things I write about. I don’t think my approach is much different than that of any writer who tackles any subject that he or she wants to take and represent seriously. It’s just that what I’m interested in writing about has been sensationalized by readers in advance, so it has a ton of prejudice to get through.

As for my goal, I’m not sure that I really know. My thinking about fiction is that a work isn’t complete and finished until it has collaborated with the reader’s imagination, and thus any novel I write will end up being thousands of novels differentiated by each reader’s personal associations. My goal in general is to finesse the invitation.

As for why my concentration is what it is, basically the things I write about have been sources of fear and excitement and confusion and emotional resonance since I was a kid. When I was young, I wasn’t afraid that thinking about horrors intricately and entertaining the pluses and minuses of their complicated powers would somehow sicken or destroy me, but I found out quickly that the majority of people just don’t want to go there. In this, I felt very isolated and unique for a long time, but when I realized that I had a gift for writing, and that I really enjoyed spending huge amounts of time making sentences match my thoughts, my weirdness became the source my originality, and that became my work’s reward.

I guess I’m not really answering the question, but I don’t think about what I do in terms of a goal other than trying to make sure that my work is trustworthy.

Re: fear as inspiration, I feel like the works of my favorite writers tend to come from exploring fear, but I don’t hear a lot of discussion of fear as a source of creativity either in criticism or in discussions of “craft.” I’ve long felt the best way to write a novel is to write about what scares you most, partly because fear is humbling and writing from fear seems to create a less domineering relationship with a text. Can you talk more about your relationship to fear as a writer and human being?

Well, I just realized as I was deciding how to answer this question that fear is really hard to talk about. It’s easier for me talk about confusion. Maybe my fear grows a protective layer of confusion really swiftly. Or else my confusion attracts my attention as a writer, and the fear is more compulsive and stormy and just sort of functions as an intense fuel. Maybe it’s that the act of writing makes what I fear become pornographic to me, and that when I have language as a buffer between it and me, my fear arouses me, and being aroused either sexually or otherwise is always kind of an inherently confusing state, for me at least. When something is confusing, I’m usually compelled by it. Why, I don’t know. Maybe in the adult world where, unless you’re a conspiracy theorist, the distinction between reality and fairytales is usually very clear, confusion is the only Santa Claus or God left?

The other day, these rowdy guys started harassing and threatening me on the street, and my French is so shitty that I didn’t understand what they were yelling, and their English was so shitty that, when I tried to reason with them, they couldn’t understand what I was saying at all. My lack of understanding made me even more frightened, and their lack of understanding seemed to make them feel even more powerful. Eventually, they got bored of my fear and left. And it was scary, for sure, but, even while it was happening, I was thinking, ‘This is so interesting. I should pay very close attention to this so I can use it later.’ I don’t know if that’s a common modus operandi for writers or not.

Among writers who might describe themselves as your followers in some sense (for instance, many in the HTMLGIANT crowd and its aesthetic circles), violence and brutality become opportunities for extreme lyricism. The destruction of the body is a way of approaching something inside, or beyond, or beneath the flesh. But your prose seems to follow the opposite impulse: your voices are (in what I’ve read) pretty flat in terms of affect, and they flatten more if anything when violence enters the picture. The narrator of The Marbled Swarm, your most florid voice by far, is really sort of evasive when the actual violence takes place. What, if anything, does this difference between your work and those of your young admirers suggest to you?

I guess I’ve never really seen that difference before. Or maybe I don’t see those writers as sharing a group approach? Off the top of my head, when I think of writers associated with HTMLGIANT who have written about violence — Eugene Marten, Sean Kilpatrick, Blake Butler, Nick Antosca, and others — their aesthetic approaches to violence seem pretty distinct.

This might sound weird, but I think of the way I write about violence as being quite lyrical most of the time. Well, except in a book like, say, The Sluts where I was mimicking online chatter with minimal distortions. But I definitely do see my depictions of the destruction of the body as always intended to unearth what’s hidden in the body, and as trying to unearth what’s operating in the expectations that the body raises, and as trying to unearth the ways in which the world becomes emotionally overwhelmed and chaotic when brutality is occurring.

I don’t see my approach as creating distance at all. My characters often have kind of hallucinatory metaphoric responses to the body and its interiority in those situations. I think maybe the thing is that my lyricism doesn’t become visible as affect. It’s true that my writing can flatten when addressing difficult situations. I think that’s a reflection of my own confusion and curiosity about brutality, and my feeling that I don’t know enough to impose my own reflections on the situation. My interest is in erasing all pretense and any veneer of expertise and just paying very close attention to what’s going on and then representing — while, at the same time, curtailing — my own responses.

When a doctor walks out of an emergency room and tells a family that their loved one died on the operating table, he doesn’t compose a poem about the death before he delivers the bad news. Maybe one of the big differences between that doctor and me is that I have months and years to figure out the right approach rather than just a minute or two. I think a flat but sensitive voice and manner are the most fair and effective approach to take with readers who might well be shocked or upset by what I want to tell them, but that flatness can be intricate and very carefully modulated and have a lot going on in it.

I’m interested in this idea of fairness. There’s this rhetoric of destruction that I often encounter in discussion of writers like you, like, “This novel will blast your spine out through your asshole and melt your brain into a hot pink puddle, it’s so good.” It seems like you’re saying that you want to talk to your readers about violence rather than somehow enact it on them through the text. How do you feel about your relationship with, and responsibilities to, your readers? What does it mean to be fair?

It’s not so much that I want to talk to readers about violence but rather that I want to simulate what violence makes me think and feel and imagine inside them. It’s more like I’m trying to use prose as the material for a designer drug that will work with readers’ eyes the way, oh, blotter acid would work with their tongues.

Fairness to me means that when my writing becomes disturbing or uncomfortable or disruptive, I do everything I can to make sure it’s a consensual and collaborative experience vis-à-vis the reader. I try to make my sentences and paragraphs become building blocks in those situations. I try to make sure that there’s enough coherence and charisma to the prose that readers’ imaginations will want to follow its instructions. Fiction is such an interesting form because it’s incredibly intrusive. I mean, it only exists in a technical, half-baked, lifeless form when it’s not being resurrected by the reader’s imagination. That intrusiveness means I have to take a lot of responsibility for what I write and how I depict it because, once the writing is activated by a reader’s imagination, they have to take responsibility for what they have willingly imagined, but their responsibility is always my responsibility too, if that makes sense.

The Marbled Swarm is, like The Sluts, structured as a sort of mystery. You’ve said in other interviews that there is an underlying reality in the novel, that there is a solution. This seems to me like another key difference between your writing and the novels of your aesthetic descendants. Their books often deny the possibility of a solution. This is part and parcel with a general skepticism re: narrative. You clearly share some of that skepticism, especially in terms of the capacity of language to represent its object. And yet you still write novels with solutions. Why?

Interesting. I’m not sure what I said about my books having solutions. I certainly don’t think they have narrative-based solutions. I tend to think of my narratives as the novels’ floor plans or landscapes. Eventually you exit, but the novels themselves are like museums or spooky houses where things accumulate and associate and then stop appearing and hopefully resonate. Or in the more deliberate examples, maybe they’re somewhat like video game narratives in that they have a point, say to rescue Zelda, but the actual rescue has no resonance or meaning in and of itself. That outcome is just what keeps you playing. And maybe a difference is that I sometimes like creating language puzzles whose facades give the appearance of clear cut narratives.

I used a mystery set-up in The Sluts because that novel’s conceit is that its storyline is an on-the-fly improvisation/exquisite corpse co-created by the novel’s many characters who are unreliable presences and fellow residents of a particular grouping of sites and message boards. The question was what’s real and what’s fake in the novel, and I saw the introduction of a potentially solvable mystery plot into the fray as an intrusive fiction, evidence that a single hand and intention had entered and corrupted something that could really only be free-floating and messy due to its mass of authors. I saw the mystery plot as a way to help readers to locate the novel’s lies. If things fit too snugly into to its artificial construct, they were distortions if not outright fabrications.

In The Marbled Swarm, the mystery story is a game, a sleight of hand being performed by a narrator who is trying to distract the reader from something that is disorganized and incapable of being represented, or so he says. The solution there is to circumvent the mystery story’s trickery and charismatic promises, to see through the neat, thick, complicated order that the mystery premise imposes on the novel’s internal world and try to find out what if anything is hidden underneath it. I guess that’s a solution in a way, but it doesn’t hold out a clear answer.

My experience of The Marbled Swarm is that I spent the whole book with my attentions sort of agonizingly divided. On the one hand we’ve got this narrator who is so damn smug that you hate to think he’s getting something over on you, so you try to watch for clues and make sure he’s not pulling some kind of trick. On the other hand it seemed less relevant whether what he said was happening than that and how he chose to tell it so I tried to watch for the underlying emotional truth. Then I reached the ending and it was heart-wrenching and suddenly I felt this intense empathy and heartbreak and I really wanted to cry but it wasn’t going to happen and I hadn’t “solved” anything. It seemed like the division of my attention was important to the ultimate effect. How do you write one text that divides readers against themselves? I mean this more in a practical sense than anything.

Thanks. I’ve always made these kind of elaborate graphs before I start writing a novel. And when I’m developing a novel, I’ve pretty much always subdivided it into what I call systems, meaning that I think of its structures and narratives and characters and rhythm and poetics and so on as separate through-lines that I develop individually via notes and in my head. Then I try to meld everything together into something seamless when I start writing. I started doing that originally because I can’t keep track of things otherwise, and I’ve only written one novel (My Loose Thread) in a linear way as a challenge and experiment, and that was like pulling teeth, as they say. I never took a fiction writing class when I was younger, and I almost never read novels that are conventionally constructed, so I don’t have the basic fiction writing skills or instincts or knowledge to be able to write novels. I feel like an interloper. So, basically, I’ve been working that way for so long that I’ve gradually figured out ways to make the systems in my novels more flexible and interactive, and, in The Marbled Swarm, I decided to take that as far as I could.

You’ve mentioned Robbe-Grillet as a strong influence on The Marbled Swarm. I should say that I’ve only read his novel Jealousy, which was a real fever-dream of a weekend. So let’s assume for the sake of conversation that Jealousy is what you meant when you said “Robbe-Girillet”; if so, then were the novel’s lessons purely linguistic, or does your book owe something of its structure to Robbe-Grillet’s as well?

Robbe-Grillet’s influence on me has been significant for a long time, but The Marbled Swarm shows the clearest evidence of his impression, I guess. The thing is, I made a deliberate point of not reading any French literature while I wrote TMS because I wanted to get the quality of the French novels I loved in the writing without risking too strong a resemblance. So, I was using my memories of Robbe-Grillet’s work, which I hadn’t read in years, as a guide rather than using his work as a model firsthand. Still, TMS is something of an homage to Robbe-Grillet, although not in the way you might expect. The chateau that appears at the beginning of TMS and then mutates throughout the novel is based on the chateau where he actually lived. I’m friends with his wife Catherine Robbe-Grillet, and she invited me to visit for a day. So my description of the chateau is actually an exact replication of his real house, although I added the secret passages and so on to make it more Robbe-Grillet-ian because, in truth, it was pretty much just a modestly decorated, conventional home.

You’ve said you write porn between novels as a sort of exercise. Porn as a category is interesting to me. I’m curious what, for you, differentiates porn from other writing.

With extremely rare exceptions, I find porn writing totally uninteresting, but that’s probably because I’m a such a prose nazi. I think visual porn is far more successful and can even be like art sometimes, even if the art is often an accident like it is in really good documentary films. I like how when you’re writing porn, you have a single and simple goal to get a hard-on and keep it there for the duration. How you get there via the writing doesn’t matter at all. Writing porn between novels is an exercise I use to clean out the earmarks of the prose I was working with in my last novel, and to write completely unselfconsciously, without ambition and in total privacy. Sometimes, although it’s pretty rare, my unselfconsciousness allows me to try things that I’m normally too rarified to consider trying because they seem so crude, and sometimes I find strange or subtle things that I can develop in my fiction later.

What was your last obsession? What are you obsessed with now?

I do a blog where I make and launch these fairly comprehensive posts about things that fascinate me six days a week. And the tempo of the blog, whereby I switch subjects and topics daily, has made my obsessions flare up and die out very quickly. So, for instance, yesterday I was obsessed with this songwriter/music stylist Michael Quercio who invented the minor but influential rock genre Paisley Underground back in the ’80s, and who has made fantastic songs with the bands Salvation Army, The Three O’Clock, Permanent Green Light, and currently Jupiter Affect. Today I’m obsessed with the work of this Austrian filmmaker Ulrich Seidl, and I’m putting together a post about him. In both cases, I’m doing a quick study of what it is about their work that interests me while they’re the center of my and my blog’s attention, and I’m thinking on the sidelines about how I might learn something from them that I can translate into my writing later. As far as a current obsession of mine that my blog can’t cordon off goes, I’m really into gingerbread right now.

I have a real personal soft spot for God Jr., because I really love video games and their weird logic, and that book probably tapped into that logic better than any other fiction I’ve read. Do you play video games much? What games influenced your depiction of the game in the novel? I thought I recognized bits of Mario 64 and Banjo Kazooie.

Thanks. Yeah, I’m a gamer. I came to playing games pretty late, in the mid-90s. I never played them when I was young, and I still have rarely ever played handheld platform games. I was pulled into computer gaming by the buzz around the first Myst, and I spent a year or two playing its offshoots and copycats then finally sprang for an N64. I’ve been a hardcore Nintendo/Miyamoto guy ever since, apart from a few spells when friends have lent me their XBoxes while they were out of town.

Banjo Kazooie and its sequel Tooie were the biggest influence on the game in God Jr. There’s also some Conkers Bad Fur Day and Paper Mario in there. And there’s also some influence from Eternal Darkness. I don’t know if you know that game, but it kept making you go insane, and you were supposed to cure yourself, but you could also play the game while you were crazy, which was infinitely more interesting. The game would start hallucinating wildly, and all kinds of strange effects would happen, like your protagonist would suddenly fall through a floor and end up wandering around in the pixels and blueprint of the game, or there would be an announcement on the screen saying your controller was unplugged and that your game data was going to be erased in 10 seconds. I tried to use some of that trippy interactivity in God Jr. too.

Eternal Darkness! That game was a huge deal to me. It’s interesting too because a lot of the most memorable hallucinations are really acknowledging the underlying reality of the situation, which is that you’re playing a game. I remember the most frightening one I saw was this sudden message at a totally anticlimactic moment saying, “Thanks for playing, look forward to seeing the rest of the story in Eternal Darkness 2!” Which was so plausible it genuinely freaked me out, in a stupid sort of “oh no I wasted my money” way.

I’m still kind of holding out hope for Eternal Darkness 2, actually, so yeah. Seriously, there used to be this MacRumors-like online forum centered around Eternal Darkness 2 that I was a member of for a long time. The really strange thing is that, unless I’ve missed something or unless you can enlighten me, there hasn’t been a game since then has continued much less furthered ED’s interest in seriously fucking with its players. Tech is so vastly more sophisticated now that one can only imagine how evil ED2 or its equivalent would be.

Here is something I always wonder about with writers. Your books are in libraries. (Several are in mine, anyway.) Have you ever checked in on them? Have you studied the gunk between the pages? If so, how did it make you feel? I shelved books for a couple years at a local library and I came to feel that the pubes and blood and curry stains and so on were deeply important to the whole experience of borrowing a book.

No, I never have, actually. But I’m definitely going to start doing that now. Weird.

Tags: Banjo Kazooie, Dennis Cooper, Eternal Darkness, God Jr., the marbled swarm, the sluts

i could read an interview with dennis every single day

Great interview: great questions and wonderful answers. Though I wonder why the interviewer has this persistent rhetoric of trying to differentiate Cooper from his “followers” on HTMLGiant?

Johannes

[…] by Johannes on Jan.05, 2012, under Uncategorized There is a super interview with Dennis Cooper over on HTML Giant. […]

Yeah, that didn’t work out so well. I like to compare the apparently-similar to see where the differences come from, but this time I don’t think my perceptions were exactly on-target. Although it looks more persistent than it was, because we did the interview in several e-mailed round of questions, so it’s not like I kept returning to it after it didn’t work out the first time — but it does look that way now!

But though his answers pretty much refuted the difference, they were some really insightful answers so it all worked out in the end anyway. Great job.

Johannes

Holy crap, the Rare developers were my absolute heroes growing up as a programming nerd. HEROES. I felt like they represented the ideal mix of professionalism, top-notch output, and amiableness/chumminess/silliness. Every day I wondered what it’d be like to work there. I must read God Jr.

I agree. Mike, I have read a number of interviews w/ Dennis since the Marbled Swarm came out and a lot of them have been seriously boring, or at least boring for long stretches, because they kept asking the same questions people have been asking Dennis for years, and which he has answered like 1,000 times over, but this one felt really fresh somehow.

Great interview.

Thanks. Here is my main advice to interviewers: read the other interviews. That way you can avoid asking those same questions for the hundred millionth time.

Word–really like this–thanks.

Really interesting interview. Thanks.

Great interview. I particularly enjoyed the questions about writing violence.

Great interview, great questions.

Does he publish his pornographic writing?

didn’t even know who cooper was before this. if the questions hadn’t been so good, i still wouldn’t. great interview.

that shits hard.

Reporting back. The videogame portions of godjr are so fun. Kind of slyly demented. I’ve been wondering about ways to write about videogames that aren’t just blah, look at me, videogames in my fiction, fart. The characterization felt most intense when the narrator’s consciousness melded with the bear’s, and it was delightfully weird, and this is very encouraging for me.

Compare this to a short story by Cory Doctorow I read a long time ago, think it involved a fat teenage girl and gold farmers in a WoW-knockoff. That story felt very much like now look here, I wrote a story with an mmo in it, isn’t that instructive, fart. And I don’t know, it was still ok for what it was. But videogames can be such a weird experience–especially when one stops “playing” and just sort of idly mingles in the game–that I was happy to see what Cooper did with it.

Yes, it’s very fun and strange.

awesome stuff. :-) Up there with his Paris Review interview

Hey Mike – was that at Prairie Lights where you had to ask for The Marbled Swarm?

I had literally the exact same experience you did earlier today – found the Butler book where I expected it to be, but, not finding the other, asked about it, and was directed to the gay fiction section.

You’d think that since I had already read this, I would have figured it out without asking, but alas.

Yep, that was Prairie Lights. It seems like a pretty okay place but I felt pretty crappy about that particular interaction. And to me the whole concept of a gay fiction section is pretty frustrating. I can see why you would separate out, say, pornography, and why you might subdivide that according to things like sexual orientation, but “fiction written by gay dudes” is just not a very useful category.

Iowa City represent! (?) !

I get historically why some stores had a gay fiction section, but presently it seems silly and reductive. Frankly if a store has a GLBT section and stocks a couple copies of Rechy’s “City of Night,” I can see if they keep one in regular fiction and one in the GLBT section. Otherwise (as mentioned about Prairie Lights) it’s as ridiculous as shelving Andrea Barrett in the science section.

Is this just one store’s simple wrong-headed decision or does it point to an inherent conservatism that infects literary Iowa City?

You know, I’m not sure. I’ve only been here since August and I don’t really know anybody, though I would like to. Generally speaking it seems like a pretty hip city, or at least educated (the college is a major employer), and I think the unfortunate shelving decision there is more an artifact of historical trends and outmoded categorization than any kind of intentional thing.