Author Spotlight

Invent your monsters sparingly: a conversation with Ned Vizzini

I sat down with Ned on a Saturday. He was feeling rough, having consumed something gnarly at a dinner party the night before in an incredibly storied Hollywood Hills house. Soon after this interview, he was struck with food poisoning. Ned’s a busy guy: his book, The Other Normals, comes out today, and the TV show he writes for with Nick Antosca, Last Resort, premieres in two days. He’s also working on a movie with Nick called Woogles, and writing a series of middle grade novels with Chris Columbus (of Harry Potter fame). And he’s a relatively new dad. Below is a transcript of our conversation, Ned drinking down gut-calming tea…

I’ve known you since you first came to LA, and I wanna know if there was any event in particular that coincided with you starting this book.

Yeah. There were two things about a decade apart. One was towards the end of high school. I was out with some friends, hanging out in the park. And I hung out with a lot of Russian kids in high school. And I had a shorter, more wily Russian friend, who’s in my first book. His name is Owen. I also had a taller, bigger, more militaristic—

A Dolph Lundgren?

In that vein. He ended up joining the military. He’s the person who told me that the US military still trains against the Russians, that when you’re doing an exercise in the military, you’re still—

Fighting the commies.

Yes. And I asked him why, and he said, “Because we’re the baddest motherfuckers around.”

That’s awesome.

Anyway, these two friends and I were in the park. I had been into Dungeons & Dragons and Magic cards in high school, and I had this realization that if we were in the fantasy world, my smaller friend would have like the dagger, and my big friend would have the two-handed axe—

They’d be the thief and the barbarian respectively.

Right, and I’d be the warrior! I’d be the leader, I supposed.

You’re the leader and the generalist.

The generalist, right. Sometimes, you just end up staying the generalist long enough to be the leader. But I realized in this group I’d be the one with the sword. And that got me thinking what it would be like to write about someone that finds themselves in a fantasy world. And I’ve always loved narratives that had that moment where the rabbit hole opens and there’s no turning back.

Fast forward to the late 2000’s. After I wrote It’s Kind of a Funny Story, I spent two years working on a book. It had the working title Urban Renewal Renewal. It was about Brooklyn gentrification, specifically about someone that tries to reverse gentrify their neighborhood – bring in homeless people, drive down property values. It’s one of those ideas that sounds kinda good, and I think that’s why I stuck with it for awhile, and it was my attempt to write a big, adult, literary novel.

Trying the Lethem thing?

Sure. I loved Fortress of Solitude, I love Motherless Brooklyn. There’s a book called The Landlord from the late 60’s [by Kristin Hunter, 1966] that covers some of this ground, that was turned into a film. I wanted to do a book like that. When I started writing, writing for teenagers wasn’t something anybody was proud of or happy to do. Except for those of us who did it – but even we got asked at parties, “When are you gonna write a real book?”

Oh Jesus Christ.

And I think I had to try to do that, and this was that book. And it was very hard. It came out very long, and ultimately—

How long?

The first draft was maybe 580 pages. But ultimately my agent told me, “This doesn’t feel like the right thing right now.” It was actually a really big relief to be told that by someone I trusted –

You don’t have to be that guy.

Yeah. And literally the same day that I got that news, I started thinking, “What about this kid that gets trapped in a role-playing world?” And I started working on The Other Normals. It wasn’t easy, either, but it was definitely closer to what I’m comfortable with, and even what I like to write about. I mean, if you’re not having any fun at all—

What the fuck’s the point.

You’re not supposed to have fun, because it’s work. But you need to have a little fun.

“Oh jesus, I have to go try to write my masterpiece now.” That’s a little silly.

I think so, yeah. My body reacts physically to writing that I don’t enjoy doing. If I’m sitting in front of a computer screen trying to write something that I hate, I’ll kind of shut down and go into a weird torpid state that’s half-depressed and half-asleep. So I have a built in feedback mechanism.

I mean, this other book exists. And maybe some day I’ll go back to it. I think I could get something out of it. It covered a lot of ground.

You think you could take the same conceit and move it into the domain you’re really good at?

It’s an interesting idea. The thing that attracts me to young adult novels is… No kid really cares about a scheme. Kids care about love and death and art. A lot of adult novels have a main character who is going to pull off something really great – he’s trying to sell his company, or she’s trying to convince her friend that she’s carrying their surrogate child, when really, it’s the nanny, or whatever. Those sorts of plots are… I don’t think that they’re contrived, it’s just that I can’t see a teenage character trying to pull off a crazy real estate scheme.

It’s weird because, and you may balk at this, but I think you and Dennis Cooper are working toward the same place, just doing it by different methods. You’re both trying to capture that non-bullshit zone, that also can feel packed full of the most toxic bullshit, but the overly complicated feelings of being a teenager. You’re just doing it by different methods. It obviously is a domain that is vital because… we’re our better selves! Well, we’re more obnoxious, but we’re more honest. You know what you want to do or don’t do at 17, and you know exactly why.

I don’t wanna quote Pearl Jam lyrics, but I will: the idea on Vitalogy that “all that’s sacred comes from youth / you’ve got no power, nothing to do / I still remember, why don’t you?” My father says it’s the most Technicolor time in your life.

Besides being a baby.

That novel has yet to be written. That’s a damn good idea.

“See In Pure Color”.

I love it.

There’s your big novel. That’ll fetch you the Nobel. See In Pure Color by Ned Vizzini.

The stock title I always have for ersatz literary work is “The Shadow In My Shoes.” But Technicolor – the highs are very high in adolescence; the lows are very low; everything is remembered. You’re going through your firsts: your first love, your first date, your first kiss, your first car accident. I honestly think that one of the big things that happens in adulthood is phone calls to customer service. I think there’s something deadening about the amount of time you spend on them. That’s something you don’t do as a kid.

It’s the bullshit. You get wedged in the beauracracy. Have you seen Barry Lyndon? It’s like when he starts doing paperwork. After fighting and loving and being a rapscallion. Then he starts signing bills. It’s the most terrifying ending in all of Kubrick’s movies, including The Shining.

That reminds me of the end of Goodfellas. And in a way you can look at being in the mob as a kind of prolonged adolescence. And that’s one of the reasons maybe that it exists as a genre. Being a vampire is prolonged adolescence. Being a werewolf is prolonged adolescence. A lot of writing is about teenagers, even if it’s not specifically about teenagers. And then a lot of literary fiction these days is about teenagers, even it’s not young adult fiction. Which I think is a trend.

Write your big “real” book and just change the label. But then you sacrifice a great audience. I remember reading A Confederacy of Dunces at 13 or 14 and being blown away, and I think that’s what pushed me down the rabbit hole of being weird and liking art, and liking weird art. It would be kinda sad if you did that, in a way. But I also say this because I’m a big fan of your writing. I read The Other Normals and enjoyed the shit out of it. And not only that, the thing that I immediately got is that your attention to language is gorgeous. There were sentences that were as good as anything in “Literary Fiction” fiction. But you don’t sacrifice the stuff that your dad taught you is important: you “deliver the goods.”

“Deliver the goods” is a phrase that my father used to say when we left a movie. When we saw Jurassic Park, he said, “That movie delivered the goods.” And what it meant was… In writing, it’s very hard to find absolutes or objective judgments that people can agree on. What is a great book? What is a great sentence? With very few exceptions, it’s all debatable. But when you’re reading a book like Jurassic Park, and a lawyer gets eaten by a T-Rex, it’s hard to debate the viscerally positive reaction that you have as a reader. Now I’m sure some people will debate it—

Lawyers.

But for me “the goods” always meant that it doesn’t matter how that film we just saw (my father was always more into film than novels) was constructed, who the actors were – in terms of delivering a story that made you sit up and feel something, it delivered. That’s the sort of thing I was aiming for in this book.

When you were in high school and playing D & D, did you ever have an experience with a particularly excellent dungeon master where you felt like completely zoned into somewhere else? Or was there always a background process running of, “Goddamn I hope no one sees me playing this and I’m getting hungry for Stouffer’s lasagna.”

Dungeons and Dragons was a sort of mythological experience, because it was never as good as the books made it seem. It was always two hours of figuring out what your character was, then somebody’s mom said they have to go home… It takes a long time to get to the part where you actually play. And then it gets good, and can get great. But my experience with a good DM didn’t happen until later in life, while I was living in Brooklyn working the check out at the Park Slope Food Coop (which is a horrible place that I’m glad to be away from). I had a copy of the Monstrous Manual on my lap. What attracted me to Dungeons & Dragons was always these charts, and the data – holy moly, there are sixteen types of dragons; and this one hordes this kind of treasure and that one hordes that kind of treasure.

The encyclopedia-type stuff.

Yes. Like people who collect baseball cards or play World of Warcraft – same thing. I was looking at this book in my lap and a woman came up to checkout and said, “Do you play?” And I said, “Not really, I haven’t for a long time.” And she said, “Well my husband runs games.” I was in my late 20s, and I started playing with these guys in their late 20s, 30s, in Park Slope. And they were mostly employed. One of them worked with little kids in a preschool. And he would say, “Three-year-olds are dicks. Just dicks. All of them. Two-year-olds care about their poop, four-year-olds you can reason with, five-year-olds are great, but three-year-olds are dicks.”

Those games, in part because these were vets and had been playing together for a long time, quickly achieved the kind of interactive storytelling a role-playing game can have. We were all fighting a minotaur once, and somebody at the table farted, really badly, and the dungeon master goes, “THE STENCH OF THE MINOTAUR WRAPS AROUND YOU!” That was a great moment. And in my work in television, I found that interactive storytelling is what TV writing is, too.

You take whoever farted in the room and Walter White is suddenly utilizing a noxious gas.

No, not like that. People fart very, very surreptitiously in television writers’ rooms.

That doesn’t sound like the writers’ room I want to be in.

Maybe there are some where people are farting away.

Sitcoms.

But when it’s cooking in the room, that’s what it feels like. Someone will be saying, “This character’s gonna do this thing,” and you realize in your head, Oh, I know what this character can do! And you jump in, and you say it, and they go, “Okay yeah great,” and you keep going and you build… it’s like Dungeons & Dragons. I was surprised by it.

And did you ever play DM with these guys? The pros?

No, I always wanted to. To me, to be a dungeon master… there’s so much preparation. It’s like a little sandcastle; it’s fun to build it. I liked making little charts and maps, but I was also a mimic as kid. I would play a video game and try to design a video game. I’d read a science fiction novel to write a science fiction novel.

I was the same exact way. Still am, I think.

I think it’s an important thing to hold on to. It’s the first step in crafting in your own work. And the people who are very good mimickers are very, very successful. I don’t think they’re hacks. I think it’s a real talent.

They have incredible pattern recognition.

Right.

Like I said, I was the same way, I was obsessed with fantasy novels. I read the Redwall series, the Eye of the World series, some of the George R. R. Martin stuff, the Scions of Shannara series, or every book in the series that was in my middle school library. I jumped series to series for years. When I was reading your book, I was like, “Holy shit, my friend is doing what I’ve always wanted to do, which is write a fantasy novel.” But you come at it from a different angle. How did you keep that in mind while you were writing the book? Both, I gotta pay homage to this and this, or what I wanna do differently?

I love Redwall. I love Lord of the Rings, although to be honest when I tried to reread it, I was shocked by how much of it was just songs. I got a little tired of the songs.

In terms of writing The Other Normals, I learned that proper nouns are dangerous. That if you invent a lizard monster called the “Ya’treez,” and they’re three feet long, and they’re on leashes, and they’re like guard dogs but giant lizards… Having made them up, they have meaning for you. But your reader is never going to have the same connection to the word “Ya’treez.” So you really have a limited number of proper nouns you can invent. Once you’ve built a really big world, in multiple books, you can sneak in as many as you want. But if you flood those in there, you’re going to lose readers.

What I liked about it too is the conceit that alternate universes then joined up. You buy it because it’s just off enough. But at the same time the characters in the other world are jaded, and there are business men, and abuses of power. It’s all that fun shit that obviously we’ve all got a taste of, especially when we’re teenagers. I bought it. Including little dog boys that run around and are overzealous and get eaten alive. I bought it.

Thank you. The conceit of the book, the idea that we live in a multiverse that is constantly splitting into alternate realities, and that two of those realities came back together after splitting and developing separately… That was something I spent way too much time reading about. I probably spent 100 hours on that stuff.

Get your Brian Greene down?

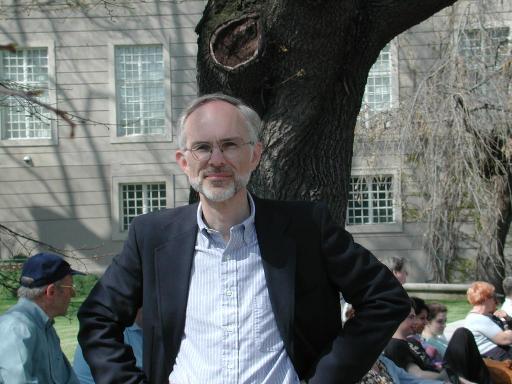

I actually liked Many Worlds in One: The Search for Other Universes by Alex Valenkin. I also spoke to a professor at my college. I went to Hunter College, and I talked to this guy when I did Be More Chill too, when I was interested in the idea of a quantum computer. His name is Professor Mark Hillery. He looks like a badass too:

He is a quantum computing researcher. His background is in physics; his specialty now is quantum computing, and he’s actually doing this stuff. The practical applications of quantum computing are a ways away because you have to have a computer that basically operates at absolute zero, without ever interacting the world outside, but from a theoretical standpoint—

Doable. And has been done, right? Transferring the tiniest tiniest tiniest bit of information?

The things that have been demonstrated with real practical value are quantum entangled states, where two particles that have no reason to be talking to one another, and are separated by long distances, effect one another because they’ve been previously paired. And I got really into books about that. And I interviewed Professor Hillery; and I have this crazy notebook filled with quantum physics notes – it’s in Florida, I donated it to the The Ted Hipple Young Adult Literature Collection. So it’s there now, not that it would really mean anything anyway; it meant very little to me. But the thing I really gravitated towards was the idea that when you remove information from a quantum system, it can come back together.

That information is a ghost.

Yeah. And then I tried to look up great losses of information in history, and I found that in 1258, when the Mongols sacked Baghdad, they went into the Bayt Ul-Hikma, the library of Baghdad that kept all of the recorded works from the golden era of Baghdad. Prior to the Renaissance, when great work in mathematics and astronomy was being done there. And they threw it all in the Tigris River. And the river ran black with ink, according to legend. And I thought maybe that moment could be the moment when so much information was lost in our universe – and coincidentally, a whole bunch of information was lost in another universe – that the two came back together and became connected.

I geeked out over that stuff because I was the incredibly obnoxious twelve year old kid reading Brian Greene and trying to teach my theater class about string theory.

I think that’s another example, as a teenager – that’s another version of baseball cards, or Dungeons & Dragons, learning real science. I had an appetite for science when I was that age that I don’t have anymore.

Same.

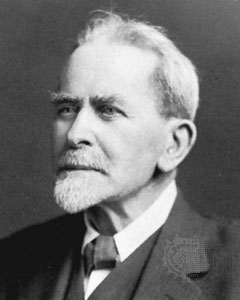

I also got into The Golden Bough by Frazer. In many ways it’s the seminal Western anthropology text. It was made by this guy James G. Frazer in the early part of the 20th century. He also looks like a badass:

Everybody reads The Hero with a Thousand Faces, but in that book I found Joseph Campbell referring to this guy Frazer, and referring to him as if obviously I, as a reader, should know who he was. So I looked him up. Frazer traveled to a lot of societies that are now gone from the Earth. Their way of life is gone. And he recorded everything from aboriginal beliefs in Australia, to Papa New Guinea, and he lived with hundreds of societies. And he tried to come up with rules for how humans interact with the idea of “magic.” And he found that magic had common threads in all societies. And one of them was the “principle of contagion.” Magic works on the idea that once I attach some of your hair to this voodoo doll, if I poke the voodoo doll, you will feel it, even though you and the doll are a hundred miles apart—

Everything has an unseen spectral connection.

Things are connected in ways that we can’t see. And I thought there was something very fascinating about that, that it was similar to the entangled states in quantum physics. So The Golden Bough book was a real eye opener for me. And it’s not hard to read; they just put out an illustrated version on Kindle; it’s fun stuff.

There’s a guy named David Graeber who’s an anarchist anthropologist—

Is this the Debt guy?

Yeah, but he wrote a little book called Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. And he says that the most peaceful societies have the biggest spectral world. That they have the most ominous border. That essentially they have to behave because if you don’t, you’re going to have a blood debt for a million years and ghosts are going to eat your fucking baby and so on and so forth. It’s that same idea – if you want to have peace here, you have to have these massive looming presences of doom. But also in war with each other, constantly at war with each other. And very diffuse – it didn’t seem at all like good/evil, God/Devil. It was much more like this cabal of invisible witches that pop up when you steal a neighbor’s chicken. But it’s that idea.

So I was obviously thinking, Ned’s gonna follow this book up because it’s going to sell a bajillion copies, that’s the hope, right?

I haven’t written a sequel yet to any of my books. I enjoy The Other Normals and every time I read it and get to the end, I feel a little bit of the excitement that I felt when I finished it. When I finish a book, I have this feeling come over my body that’s the opposite of the torpid feeling I get from working on a bad book. I feel electric all over. Right now I don’t have any plans to do a sequel to it, though, because I have other things going on, and because in my mind sequels are always a little cheap. They are. Show me the sequel that’s really really great.

Godfather Part Two.

Well that’s a film.

You’re right.

I liked Imperial Bedrooms. That seemed like the right way to do a sequel: wait a long time and come back to it. I don’t particularly like Michael Crichton’s The Lost World, which is just, “We’re back on the island! Dinosaurs!”

“It’s happening AGAIN!”

I feel that he was at his best moving from project to project.

Although you could have so much fun with the multiple universes.

There could be a lot of… As I heard Seth Grahame-Smith say after a screening of Dark Shadows when someone asked about a sequel, “Let’s let the market speak.” Anything’s possible, but it’s not something I’ve planned right now.

While writing this book did you have any difficulties separating in your head the different languages of screenwriting and book writing? Because I know you’re doing both pretty simultaneously.

No. I think I learned from screenwriting. I think there’s an assumption that if you write a book you can write a screenplay, and that’s totally bogus. Screenplays are not easy; they’re a different beast. But just living in LA, I learned a lot about story. And I’d like to think that story is story.

Sure. Story is the totem, here. You must worship at the idol of story, and then you’ll be bestowed riches from the heavens.

One funny thing is in Adaptation, when Donald Kaufman is reading that book that helps him write, it’s Robert McKee’s Story. I thought it was an invented book from the movie, but it’s a real book! Hundreds of thousands of people read and revere… I haven’t read it. I think sometimes it’s good to keep away from that stuff because you end up sounding like everybody else.

You start pumping out the pattern. Fill the slots, cobble it together, here’s your thing. I think you get these people trying to replicate these patterns, not realizing the whole reason these patterns exist in the first place is because it comes from one… You do it naturally. Every minute we walk around and look at the sun in the sky, we’re constantly pasting experience into that form.

Yeah. We have an innate desire to create narrative. I think it’s what makes fiction work. One of the most dangerous things that can happen to you as a writer is when you start questioning your narrative sense, in the positive or the negative. You really have to be able to say, “Oh, there’s a reason this isn’t working. Now I have to go find it.” It’s always a pain in the butt. But if you convince yourself, “I’ll just keep going, no one will notice that part doesn’t work, because something cool happens later—”

Insert explosion.

Or a love interest – then you’re screwed.

The converse can be bad too. Sometimes you really love a turn in your story, but you don’t wanna go there because it’s not how you planned to do it, or it’d be hard to write what comes next, so you stick to your plan. That’s how you get books that don’t work.

Do you feel yourself, with this book, fearful that, in the grandest way possible, you’ve mined the young adult territory? Do you feel a pressure to go, holy shit, how do I go attack this again?

No, that’s not something I worry about. The thing that I’m worried about with this book is that it’s very different from my last book, and that it’s the first time I’m doing something with a fantasy element. It’s been good to me so far. I had sold the book and was editing it when I got the opportunity to co-write House of Secrets with Chris Columbus. I don’t think that would’ve arisen had my agent not been able to say, “Well, Ned can write this stuff.” So it opened doors. I’m not interested in doing the same thing over and over. I’m not interested in doing It’s Kind of a Funnier Story. I think there’s plenty more in the young adult book world for me to do. My next project is going to be more realistic, and… I don’t really wanna say anything else about it, except that it’s going to hinge on the relationship between a kid and his uncle.

I remember you mentioning that years ago.

It’s still gonna happen, it’s been delayed by House of Secrets and—

Having gigs.

Having gigs. But I think that’s good too, because I’m collecting material for it. And I want it to be about the artistic impulse, about how as a teenager you don’t realize the power that you have when you say, “Hey I wanna make a comic book.” You can up and do that kind of stuff. When you’re in your 30s, everybody just – unless you’re an artist already – they’re think you’re weird, and not just weird, stupid and irresponsible. And even if you are an artist, they think you’re stupid and irresponsible. And a lot of young people don’t realize the freedom they have as artists, and I’d like this book to explore that a bit. That’ll be a young adult book, and after that, I don’t know. I’d like to write lots of different things, and I didn’t die in my 20s, so I’m going to be alive for a long time now.

You say that like it’s a curse. Somedays it feels like a curse.

I really revered young romantic death as teenager. I don’t think I was alone in that. I also fell prey to picking up artistic heroes and thinking that I had to live like them. Not realizing that I can be my own person and I—

Don’t have to blow your brains out.

Yeah, and not just that, also… You don’t have to live like a person because you love their books. But the blowing your brains out, that’s part of it.

We’re ending there.

Tags: chris columbus, dungeons and dragons, fantasy, house of secrets, interview, last resort, max landis, ned vizzini, nick antosca, the other normals, tv

This was fantastic. Thanks, guys.

This was great!

Thanks, Ken.

[…] Ken Baumann and Ned Vizzini sat down for a conversation at HTML Giant. […]

It is heartbreaking to read this today.