“Narrative Gold” — (In the Memoir Swamp) — Talking to Seattle’s Elissa Washuta

*****

*****

Rauan: why is most Memoir so bad, so boring (and in so many instances just a kind of “grief porn”)??

Elissa: Memoir is the genre most often entered by celebrities. It’s also full of books by people whose lives have been stricken by remarkable tragedies or circumstances that are marketable to readers hungry to know about other people’s lives. If we want to know about that secret wig that Andre Agassi wore for years during his tennis career, he’ll gladly sell us a copy of his memoir, Open. If we want to know how Dustin Diamond felt about playing Screech, he’ll give us an earful in Behind the Bell. Politicians use memoir to push their agendas; the infamous use it to set the record straight. Many celebrity memoirs are ghostwritten, and I get the feeling that the people on the covers don’t think much about craft.

Memoir isn’t working, I think, when the author has no ear for language, no eye for image, a limp voice, and an insistence upon a narrative arc that delivers an easy revelatory triumph at the end. In mediocre-at-best memoirs, the narrators balk when faced with the opportunity to tease out the most complicated tangles of their experience–sometimes, the revelation of their own complicity in what’s gnawing at them. That’s narrative gold in memoir: reading about a character with agency is much more compelling than reading about a helpless victim. I certainly do not wish to judge or take away from the lived experiences of the people who wrote the memoirs that I’ve found the most to critique in (including Prozac Nation by Elizabeth Wurtzel and Lucky by Alice Sebold), but in memoir, there’s a problematic tendency to close the gap between art and life that allows the most exciting work to take place.

I read and listen to (audiobooks of) lots of memoirs. I’ll listen to any memoir that Seattle Public Library has available. While I do think the memoir genre is full of duds, I’ve read so many thrilling, vibrant, well-written memoirs in the past few years, including Rat Girl by Kristen Hersh, The Guardians by Sarah Manguso, Confessions of a Latter-Day Virgin by Nicole Hardy, The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon, Yoga Bitch by Suzanne Morrison, Bad Indians by Deborah Miranda, Lying: A Metaphorical Memoir by Lauren Slater, The Adderall Diaries by Stephen Elliott, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City by Nick Flynn, and Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen. Each of these is complicated and compelling in its own way.

*****

*****

Okay, so that was the first part of my latest Seattle Author Spotlight (# 9, featuring Elissa Washuta).

*****

Elissa‘s memoir (My Body is a Book of Rules) is coming out from Red Hen Press in 2014 and she is currently at work on a 2nd memoir entitled Starvation Mode. Elissa is proud of her European and Cowlitz/Cascade Indian Heritage and teaches American Indian Studies at UW where she received her MFA in Creating Writing. Recently Elissa and I met and compared Bi-Polar disorder notes, chuckled about bad memoir, reminisced about The Dodge Poetry Festival, etc, etc…(Elissa, as you will see, is whip-smart, writes beautiful and engaging prose, often employing a healthy, poignant and sometimes biting sense of humor while discussing serious topics such as rape, mental health struggles and diet/body issues.)

So, here then, anyways, is the rest of the interview portion of this Spotlight, followed by a brief bio and then links to previous Spotlights.

Enjoy!

*****

*****

Rauan: Your memoir, “My Body Is a Book of Rules” will be published next year by Red Hen Press (congratulations!). But, tell us, please, how it differs from all this bad, boring Memoir?

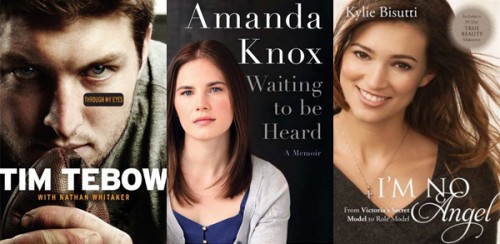

Elissa: I’m not running for president; I was never an NFL quarterback; I have not spent any time in an Italian prison.

Early in the writing process, I read memoirs concerning similar subjects to mine. I found that many of the most commercially successful memoirs about bipolar disorder and rape were more concerned with what happened than the ways complicated emotions could be explored through prose. I also think that the narrative structure of many of those memoirs set up the narrator to travel through the story as a victim-turned-conqueror, slaying the beast and banishing the demons at the end. But I am skeptical of the redemptive power of the narrative arc.

I didn’t set out to write My Body Is a Book of Rules as the story of these things that happened to me and how I overcame them in a triumphant way. I started with theme (the hard work of mastering a troubled body) and form and used my life as raw material. I use such forms and setups as a college term paper, a Match.com online dating profile, lines from Law & Order: Special Victims Unit stacked against a personal recounting, and a revision of a real letter from my college psychiatrist. Each time I use a new chapter to circle around the same problems, I fail to solve them and dig myself into a deeper hole. I believe the most powerful way to evoke emotion in a reader is not to describe how something felt, but to build it on the page; formal gymnastics helped me do that with this well-trod, difficult subject matter.

*****

*****

RK: To give our readers a taste of your work could you please provide us a brief(ish) sample? (preferably from My Body Is a Book of Rules) ?

EW:

Originally developed to treat epilepsy, Lamictal is now also part of the bipolar buffet, and you will be asked to add it to your plate when your doctor changes his mind about the whole depression thing. The pharmacist’s warning will barely register, and you will not monitor your skin for rashes—after all, being medicated means being warned of death at every turn—and soon, you will come to rely on these little blue shield-shaped saviors, which grow in size as the milligrams increase, but first, you will be tested by a month-long period of terror in which your dosage will creep up toward 100 milligrams for fear of startling your immune system. Eventually, your mood will level out. Lamictal’s mood stabilizing properties will briefly offer to save your fucked-up life, but no sooner will your doctor declare you stabilized than he’ll see you before him, howling, a speckled egg, abdomen exposed, your shadowed ribcage a spectacle, your blooming rash a once-in-a-career wonder. Your doctor will not look into the broken panes of your eyes as you ask him whether you’re going to die. He will lean in close to look at the flush that had the potential to turn deadly but has been sapped of its danger, will say you caught it early enough to immobilize the reaction. You’ll discontinue this drug that saved your mind, and you’ll be just fine.

He will marvel at the marbling of your skin, cradling your wrist in his arm, his eyes macro-lens close to observe the rare bird of you, plumed in flannel pajama pants with dazzling sneakers poking out like showy tail feathers, and he will whisper, “I’ve never seen it before.”

*****

RK: It wasn’t easy for you to find a home for your book. I think you mentioned that you had 68 agent rejections and then over 40 from publishers. But some publishers did respond saying they loved yr manuscript but they thought it would be too much of a risk for them. This is confusing to me because if they loved it then surely others would also. Are they saying then that the target audience is less sophisticated (more stupid)? Or were those who “loved” yr work just not brave enough to go to bat for it (and for you)?

EW: I can’t pretend to begin to understand how the publishing industry works, but it’s clear that some memoirs are more likely to be picked up in an airport bookstore than others. I recently listened to Amanda Knox’s Waiting to Be Heard, which received one of the largest advances of all time, $4 million. Knox was a compelling audio narrator, and the material was interesting, but that kind of memoir is doing a very different thing than mine–it’s giving readers information and a perspective we’ve been curious about. Sarah Palin, Dick Cheney, George W. Bush, the Clintons, Keith Richards, and many others fall into this category. Are debut authors of literary memoir competing with them, on any level? I don’t know. To me, these seem like completely different genres.

It’s true that agents and publishers have always written kindly about my memoir, but there are financial concerns, and they have to think about how many people will be interested in the book—their own love aside, how many will buy it? I hope My Body Is a Book of Rules will be loved by a broad audience, including college-aged and teenaged young adults and bookstore browsers everywhere. This book is different, but that doesn’t mean it’s not accessible.

There is tremendous pressure, when presenting a manuscript, to be able to sum it up in a tagline, paragraph, or elevator pitch. I want to write books that are knots that I can just barely untangle. These don’t sound like slam-dunks. My Body Is a Book of Rules also needed to come just a bit more into focus with the help of an astute editor, and the stars aligned and Red Hen Press was the perfect place for that work to happen.

*****

*****

RK: You mentioned that when you were a little girl your Mom would tell you “what it meant to be Indian.” Can you tell us, now, what it means to be Indian? And can you talk about what some refer to as the government’s “extinction policy”?

EW: I am Cowlitz/Cascade because Mom is, and Grandma was, and her mother was, and so on; that identity was tied to the Columbia River Gorge, but it could be carried anywhere, including to New Jersey, where I grew up.

Elissa’s great-great-grandmother, Mary Wil-wy-ity, and her daughter, Abbie Weiser Reynolds Estabrook (Elissa’s mother’s grandmother)

Being Indian is too complicated to successfully explain briefly here. The experience differs for every person. I am an enrolled member of the Cowlitz Tribe and also a descendent of the Watlala (Cascade) people. I teach American Indian Studies at the University of Washington– it’s important to me to educate students about who we are. My Cowlitz and Cascade family has lived in the NW for more than ten thousand years. Being Cowlitz/Cascade means, to me, learning about native plants and how to use them, learning from my mother and aunts about our family and about traditions like huckleberry picking, and figuring out how my Indianness is embedded in my body.

The federal government has implemented many policies to carry out the extermination of Native peoples: splitting up commonly-held lands into individual allotments and giving away the “surplus” to non-Indians, stripping children of their indigenous knowledge and replacing it with Anglo-American teachings and the English language in boarding schools (while physically, sexually, and emotionally abusing the children), outlawing ceremony, and much more. The people who implemented these policies often believed they were helping Indian people by “civilizing” them.

The destructive federal policy that I’ve dealt with in memoir is the use of blood quantum, or degree of ancestry for an individual of a specific tribe (or tribes in total). Blood quantum has been used for tribal enrollment (though not universally) and to determine eligibility for the government programs that (to state it briefly and too simply) form part of the compensation for the lands ceded during the treaty-making process. Blood quantum is not a Native invention; traditionally, tribes had other means of recognizing ancestry and membership. Intermarriage is quickly causing Indian blood quantum to diminish, and if we must continue to use this troubled system of identifying membership, tribes will have to exclude future generations, regardless of their cultural and familial connections. Now, the question of “how much?” is embedded into the American consciousness, and it has led to a mess of identity issues for Native people who identify with their cultures and families but don’t present a blood quantum consistent with what American minds associate with “real Indians.”

*****

*****

RK: Tell us, plz, about some of your favorite books and why they’re important to you?

EW: The book I have loved the most is The Tattooed Potato and Other Clues by Ellen Raskin. It’s a YA mystery novel about a seventeen-year-old art student who ends up solving mysteries with her artist boss, and it’s weird as hell, and grim. It was the first book I read from the “big kids” section, and I return to it often. I love its structure.

Another favorite is The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides, a novel I dissected in writing every time a college professor gave me the chance. I love this book because it tells a story about girls, a story that makes its own case for mattering. The same is true of Elissa Schappell’s Blueprints for Building Better Girls, another book I adore.

Lately, before I start writing, I often read a couple of poems from Natalie Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec, my favorite poetry collection.

*****

RK: You like, it seems, to spice your writing and readings up with humor. On one video of you reading (at Hugo House?) I think you said something like because of your recurring and various health issues you were worried that the Insurance Company would take you out back and shoot you. What are your thoughts on “humor”? Is it too policed? Do we need more of it? What’s humor like in Native American art and culture?

EW: Humor is one of my favorite literary tools because I deal with some dark, bleak, sometimes intense material. That can alienate or burden a reader after a while. Humor is important to me for the same reason it is important to Native peoples: it is a means of survival, alleviating pain. But it has deep roots in Native cultures, from long before the hard times that came with colonization. Humor varies among Native cultures, but in the Northwest, traditional stories can be pretty funny. There’s a lot of sex jokes, and a lot of excrement.

An infusion of humor in an account of a painful experience can be incredibly powerful. I think there’s sometimes a tendency to avoid humor in order to avoid making light of a situation, but I find it’s one of the best ways to connect with readers. I don’t think humor is too policed; I like the idea that, in my country, we enjoy free speech, and we also have ways of letting one another know when humor has been oppressive or otherwise offensive. We’re all free to make any joke we want, and our community—whatever that is—will be free to call us out on it.

*****

*****

RK: To give our readers a 2nd taste of your work could you provide us another sample of your work?

EW:

When I was five, my kindergarten teacher split the class into Pilgrims and Indians with construction paper costumes to teach us about our national heritage; my parents had explained to me that I was Indian, and the classroom taught me what that meant. When I was six, my dad taught me how to spell “Cowlitz,” and I wrote it at the bottom of my drawings. When I was seven, I became obsessed with mermaids, certain that I could fuse my legs into a fin if I pressed them together firmly enough under my modest sub-desk plaid. At eight, I created dioramas of buildings where other Native people’s ancestors slept, and though the teacher told me this was my heritage, I was not certain that I believed in cacti or mesas, having never seen them.

(From My Body Is a Book of Rules)

*****

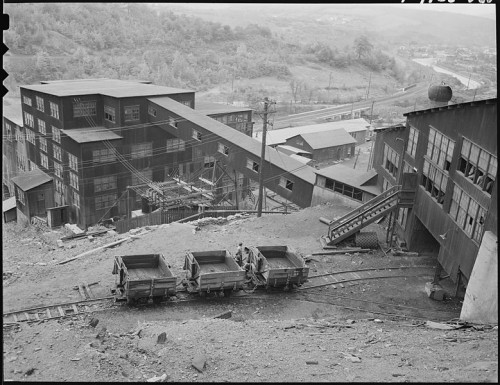

RK: Tell us a bit your father’s side of the family? I think you mentioned that they originated from Galicia (Poland/Ukraine area) and that some of them were coal miners here in the U.S. ??

EW: My dad was born in Pennsylvania’s Coal Region. His father’s parents emigrated separately from Galicia at the turn of the twentieth century, and many of the men took jobs in the coal mines, allowing the previous wave of immigrants to literally rise up to above-ground mining jobs. These included my dad’s other set of grandparents, Irish-Americans who had arrived during the Potato Famine. To a few of the men in that generation of my family, the mines brought black lung and took fingers. I spent a lot of time with my grandparents in Pennsylvania growing up—they and Dad and my uncle are great storytellers. Their stories are so lively and sturdy that they have become indistinguishable from my own memories.

*****

*****

RK: Can you talk a bit about yr 2nd book, Starvation Mode, which you’re currently working on?

EW: Starvation Mode began as a memoir of my work to bring traditional NorthwestCoast foods and medicines into my life in order to treat illness, including bipolar disorder, celiac disease, long-term hormone imbalance and ovarian cysts, and digestive ailments related to gallbladder surgery. It has grown to encompass the diet obsession that drives me from one epiphany to another, the complications in my genes that make ancestral reenactment impossible, and the futility and danger of working to crack open my body like a coded lock. This is, in a sense, a food memoir, but it is a food memoir about war and self-punishment. The book deals with, among other things, my Cowlitz and Watlala ancestry and the hanging of my great-great-great grandfather for treason not long after he co-signed the Treaty of Kalapuya, the Coal Region and how my dad’s side of the family came to be there, repeatedly seeing myself from the future on the bus and at Safeway, genetics and epigenetics, fencing, and blind devotion to every diet that promises to make me live forever and eliminate my belly.

*****

![]() RK: Aren’t you too young to write Memoir? (I mean, really, aren’t you?)

RK: Aren’t you too young to write Memoir? (I mean, really, aren’t you?) ![]()

EW: People sometimes confuse “memoir” and “autobiography”–for sure, I don’t have enough material to write a tome on the order of Bill Clinton’s My Life. Other times, there’s an expectation that if I have a forthcoming memoir at 28, I should be celebrating my freedom from an Italian prison after a high-profile murder case or might be a young, outspokenly Christian NFL quarterback. The bare facts of my story are not unusual: I was a college student trying to understand rape, trying to manage bipolar disorder and its treatments, trying to define my identity, and trying to keep a high grade point average.

Too often, I feel that young women writers are treated as though the work we produce is just preparation for the work we will produce when we have matured into relevance, especially when we are telling stories about being young women. But that’s not all mani-pedis and appletinis–we can fall into deep chasms, and some of us write about every jagged rock we hit on the way down.

*****

Brief Bio:

Elissa Washuta, a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, is the author of My Body Is a Book of Rules, a memoir forthcoming from Red Hen Press. Her work has appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education, Filter Literary Journal, and Third Coast. She recently received a Potlatch Fund Native Arts Grant, an Artist Trust GAP Award, and a 4Culture Grant. In 2012, she was named an inaugural fellow in the Made at Hugo House program. She serves as adviser and lecturer for the Department of American Indian Studies at the University of Washington.

***

here’s a Video of Elissa reading at the Hugo House

***

Previous Spotlights

Tags: Elissa Washuta, Seattle Author Spotlight

[…] Washuta talks about the nature of memoir in this interview for […]

Best interview I’ve read with any author for a long time. Great piece, and the book sounds phenomenal. PS I still hate Blake Butler.

[…] This interview on HTMLGIANT made me want to read Elissa Washuta’s memoir (it’s coming from Red Hen Press in 2014)-and provided further food for thought on memoir more generally. […]

[…] of the most interesting Seattle Author Spotlights that I posted featured Elissa Washuta. And her book “My Body Is a Book of Rules” has just released! You can read the […]