[In this series I will think aloud about the multifarious process of publishing a first book.]

The first time I ever cursed was in the fourth grade. I’d just transferred out of Catholic school to public school. I was standing at the door to Mrs. Rogers’ portable classroom, friendless and waiting to be dismissed, when I mouthed the word “shit.” Then I whispered it. Then I said it. Just like that. Shit! I couldn’t stop smiling.

I didn’t feel the same exuberant freedom again until I was 18 and shaved my head. I remember looking into the rearview mirror of my ’86 Le Sabre after I’d buzzed my hair off; I couldn’t stop grinning.

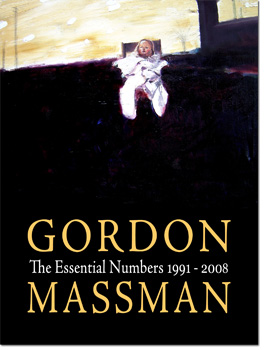

I’m 33, and it just happened for the third time. For weeks I’d been awaiting the publication of my first book, but I’d become petrified of its first poem—that it IS the first poem in the book with its one goddamn, one fucker, and one motherfucker in 20 lines, and that certain people (such as my Italian Catholic grandmother) would read that first poem and get their feathers ruffled, feel disappointed that I’m actually such a no-good heathen. What were my publishers thinking?

This poem will always be the first poem of the book. It’ll always set a tone, which is why it’s the first poem. It’ll be there to remind me that I like to run my mouth (but also to remind me that I enjoy mis-hearings, misunderstandings, and even occasional misanthropy). That’s a lot of pressure for one little guy in a sea of bigger fish (it’s close to the shortest poem in the book).

Then I got my author copies in the mail, and I realized that the language I very deliberately chose for this poem—and every poem—simply embodies my fourth-grade epiphany or my freshman-year hair buzz, those times I used my body as the subject of my own story, pleasuring in the language of the forbidden, simultaneously defining and deferring definitions (the eternal tension of différance), and felt the freedom therein.

Basically, I’m saying that if I ever go to hell, I hope it’s because of my motherfucking mouth. That’s not all I’m saying, but it’s a start.

I picked up

I picked up