Kate Durbin interviews Rob Wittig & Mark C. Marino of “Tempspence”

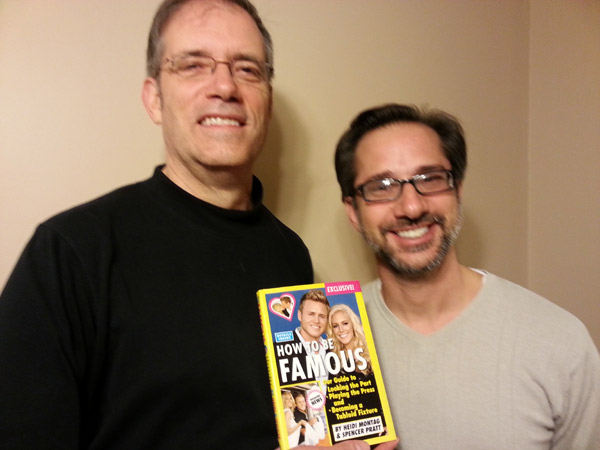

In January 2013, reality television star Spencer Pratt offered use of his official Twitter account to electronic literature writers Mark Marino and Rob Wittig while he was filming Celebrity Big Brother in London. The result was a netprov (networked improv narrative) project in which a fictional British poet supposedly hijacked Spencer’s phone and identity, was then unmasked, and began to promote his own poetry. The fictional British poet wound up encouraging Spencer’s followers to write their own poems. Originally titled “Reality,” the project was dubbed Temporary Spencer or “Tempspence” by fans.

As someone who follows and re-tweets celebrities on Twitter for my own conceptual Twitter project, I came across Tempspence naturally, as I followed and re-tweeted Spencer Pratt already. When Spencer / Temspence tweeted that he was buying his girlfriend Heidi Montag my collaborator Amaranth Borsuk’s digital poetry book Between Page and Screen, the top of my head exploded, in a post-Dickinson-cyberspace kind of way. My own transcription project of an episode of The Hills made Tempspence particularly fascinating to me, since I’d been studying the multi-faceted character of Spencer Pratt for a long time. And of course I cannot resist any project that implodes the false distance between mediums / worlds normally considered totally disparate, such as reality TV and avant garde literature. So, after eagerly following the Tempspence project to its completion, I knew I had to find out more about the masterminds behind it.

Kate: Tell me how Tempspence came about. It seems a miracle of literary and reality TV worlds colliding!

Mark: Spencer was a student in my Advanced Writing course at USC. During that class, Rob and I ran a netprov called F.A.I.L. (Fantasy Automated Investors’ League) with the students. That game introduced Spencer to #netprov, but I believe he has a natural affinity for improvised performance after years on Reality TV. He’d also seen my Workstudy Seth tweets and commiserated about having someone go rogue on your Twitter account. So as January approached and he knew he’d be sequestered from Twitter for three weeks (or less), he asked if I’d be interested in running a netprov through his account. He initially proposed me Tweeting as him on a phone hidden in the Big Brother house, but since the logistics of that were too difficult, given the distance, the constant surveillance, and the time difference, I proposed the “lost phone” idea. Playing a fictional character in England who had found his phone would be much easier, and so on Jan 1, Heidi Tweeted that Spencer had lost the new phone she’d bought Spencer for Christmas during their wild New Year’s Eve celebrations.

Kate: I love this on so many levels. I love that Spencer, the reality TV celebrity, was your student, Mark, and I also love that he was the one who approached you to run a netprov through his account. I love that he “got” the game, and was willing to play, although I think you are right that his work in reality TV would naturally attune him toward improv performance, as well as performance mediated through the latest technological mediums, trying out new ways of reaching an audience. Spencer on The Hills was such a fascinating character–you could almost see his mind working as he improvised scenes, manipulating situations to evoke audience response. It sounds like he saw a similar opportunity in working with you two.

Did Spencer talk to you at all about what he specifically hoped to gain through the experience, or why he wanted to do this? And why did you guys want to do it? Was there a particular experience you wanted to have, or to create?

Mark: Well, Spencer’s account is almost at 1 million followers. Almost. And getting to know him and his oeuvre, I have come to recognize him as king of the publicity stunt. That’s why it was almost impossible to shake people’s belief that Spencer was the one behind the account the whole time. Also, the literary element, the poet and his games, allowed Spencer to do something more sophisticated with his image than say, blowing his fortune on the 2012 apocalypse. For Rob and I, it was a chance to bring netprov to a huge audience that had not previously been exposed to it — except in the very general sense that Spencerpratt account is basically always netprov. But playing with Spencer’s image was the ultimate lure. Like I was saying, as a reality tv star, Spencer lives a kind netprov, and yet people always think they’re getting the “real” him. They were aghast (or pretended to be) at the thought that someone other than Spencer would Tweet from his account either as a stunt or having stolen or found his phone. I would get tides of hate from all sides. READ MORE >

25 Points: Eyelid Lick

Eyelid Lick

Eyelid Lick

by Donald Dunbar

Fence Books, 2012

88 pages / $15.95 buy from Fence Books

1. The Table(s) of Contents might be my favorite part. Or maybe it’s the few pages after the Table(s) of Contents, the part where you realize that formally, Eyelid Lick is fucking everything else up.

2. Formally, I can only compare Eyelid Lick to A New Quarantine Will Take My Place. There aren’t “poems” and it doesn’t really have sections. There are regions of the book that are three to four pages long and that are like themselves, and not really like the rest of the book, but still more like the rest of the book, than writing that is in any other book.

3. Tonally, Eyelid Lick is all over the place. It can be funny or sad or violent or sincere or religious or irreligious, but it’s always dancing on emotions, linguistically and sonically engaging, and beautiful.

4. If the book has an analogue to doing drugs, it would alternate a different drug every 4-6 hours for 2-3 days in a row. In some respects this is exhausting, but at the same time, a really exciting and unique vacation from Contemporary American Poetry.

5.

And in case I die, I paid one point two million

for this mausoleum, and you’re telling me

it’s only partially real? I paid a cool four

million for this airplane and you’re telling me

it’s an angel? I spent a week’s worth of food stamps

on a week’s worth of food and here we are:

shot to death in an electronics store? Smeared across

some new Iraqi highway? On the porch, electric green

from the reflected plants, imagining the blood clot

that stops the brain?

6. In real life, Donald Dunbar is one of the most generous and beautiful people that I know. He regularly cooks meals for friends. I have slept on his couch. I know lots of people who’ve slept on his couch. He would probably let me move in and build a blanketfort in his living room if I needed a place to live bad enough.

7. I want to say that maybe the exhaustion I felt when reading the book might translate into tedium for some people. Some people might also think that sleeping on someone’s couch is undignified and that no one over the age of 8 should have a blanketfort in the living room. But fuck those people. This book is for drinking three more PBRs, smoking a bowl, and waking up on a couch or in a blanketfort. This is not the kind of poetry that encourages taking a cab home early.

8. There’s something vital about Eyelid Lick and the way the book seems to want to be read wildly and to the point of exhaustion.

9.

America, mute informant,

pulse of the goat, America,

the slowest surgery,

the flowering land of God,

I eat all your words

and turn your children into knives.

10. One of my favorite conversations that I’ve had with Donald Dunbar includes this bit of dialogue:

“Outside of Brooklyn, nobody fucks with poetry from Portland.”

“What about San Francisco?”

“Ok, yeah. San Francisco can fuck us, but only in our pee-holes.” READ MORE >

June 27th, 2013 / 11:18 am

Joe Wenderoth & Colin Winnette Talk WCW’s Spring And All

For this series I’m asking the writers I love to recommend a book. If I haven’t read it, I read it. Then we talk about it.

For this installment, Joe Wenderoth recommended Spring and All by William Carlos Williams.

Joe Wenderoth grew up near Baltimore. He is the author of No Real Light (Wave Books, 2007), The Holy Spirit of Life: Essays Written for John Ashcroft’s Secret Self (Verse Press, 2005) and Letters to Wendy’s (Verse Press, 2000). Wesleyan University Press published his first two books of poems: Disfortune (1995) and It Is If I Speak (2000). He is AssociateProfessor of English at the University of California, Davis.

Colin: First off, I’m interested in why we read what we read. Can you talk a little about what brought you to the book? What were the conditions that led to your picking it up for the first time, and why did you want to talk about it here with me?

Joe: I’ve been a full Professor for about 3 years now—I guess they don’t change the bio on the UCD website. why bother with correcting this? well, to become full prof you have to fill out a bunch of forms, and I would hate to think that it was all for nothing. I was doing a reading at the new school in ny and Robert Polito introduced me, saying that Letters to Wendy’s was a uniquely indescribable book, akin to Spring and All (at least in that respect). anyhow, as I had not read it, I figured I should. it took me quite a while to figure it out, but the process was always rewarding so I kept on with it and ultimately found it to be one of the best books in american english. it is a remarkably prescient book—seems like it could have been written yesterday. it seems especially remarkable in that it was written in response to “The Waste Land” (and Eliot’s much celebrated poetics), and in that its implicit criticisms of Eliot’s poetics was so far ahead of its time. it is hard for me to believe that Eliot was taken as seriously as he was. now, only undergrads are fooled, but back then, Williams was quite in the minority, and totally obscure as a poet and thinker.

Colin: Walk me through your experience of this book. It takes so many forms simultaneously: criticism, manifesto, a book of poems, a single poem, self-analysis, polemic, just to name a few. Do you have more than one approach to reading it? Do you/have you studied it in any kind of rigorous or structured way, or do you read it simply for what sticks?

Joe: I have read every word closely. I’ve taught a class on it—a class reading just this book. and I’ve taught it in other courses, too, in l briefer focus. it took me awhile to see how it all fits. I don’t see it as a single poem. I see it as a manifesto, with poems interrupting every now and then to demonstrate his thinking.

Colin: Could you bullet point a few of these “implicit criticism”s you mentioned before? Not as a defense of the statement, but rather as a potential guide/reference readers picking upSpring and All for the very first time? It’s largely an experiential text, though Williams is fairly direct when positioning himself relative to his potential critics and other approaches to poetics, but I’d love to hear your particular articulation of these criticisms, stated as simply as possible.

Joe: In a letter to James Laughlin, Williams wrote: “I’m glad you like his verse; but I’m warning you, the only reason it doesn’t smell is that it’s synthetic. Maybe I’m wrong, but I distrust that bastard more than any other writer I know in the world today. He can write, granted, but it’s like walking into a church to me.” In a letter to Pound, he referred to Eliot’s work as “vaginal stoppage” and “gleet.” In many ways, the church Williams refers to might be taken as a symbolic manifestation of the shelter of so-called Western tradition. Eliot left the church… or rather, the church fell down. And what did he find outside of its ruins? A Waste Land. A place where our alleged intelligence—especially concerning our conception of ourselves—has failed utterly. A place of cruel stupidity (which he mocks), impotence (which he grieves), and despair (which he attempts, albeit somewhat half-heartedly). Well, Eliot then went back into the church, however gloomily. Its ruins was enough, apparently.

In any case, Williams and Eliot are in agreement about the failure of the church, which is to say, the failure of our conception of ourselves. Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche, Einstein, Freud, etc…. The progress of Science, both poets agree, has obviously caused a great disruption, emptying out our previous conceptions. What they disagree about is the significance of this disruption—its impact on human consciousness. When Williams experienced the church falling down around him, he was heartened. He saw his departure from the hushed space of tradition as a great liberation, and the collapse of the church as a stroke of luck. An escape from a gloomy place. The failure of past intelligence (traditional understanding) is something he acknowledges—but it does not cause him distress… because he feels The Imagination is still in working order, and still functions—perhaps functions even more powerfully as it becomes more capable of shedding false intelligence. READ MORE >

25 Points: Family System

Family System

Family System

by Jack Christian

Center for Literary Publishing, 2012

57 pages / $16.95 buy from Amazon

1. On the inside of most of my books, I often write down the date and place I acquired the book or where I was when I started reading it or who gave it to me or what state of mind I was in at the time. Some kind of carving goes into the tree. Maybe it’s indulgent, this insisting on making my DNA / my curry stains present and part of. It makes me think of K holding the door open for me and saying, “I’m not sure nostalgia is as bad as we think it is.” This book, Jack Christian’s Family System, has two pieces of handwriting in it. It says, on the very first possible page, “Boston, MA, 2013. Given to you. You were drunk.” On the next page is Jack’s signature.

2. A text message received while I was at a goodbye party: “Everything becomes important so quickly. Being around my parents has made me feel so young again.”

3. While I was in the basement of the Cantab Lounge in Boston, I fluctuated myself to younger and in the middle of a few years ago. I was in Asia reading this line from Christian’s poem, “Northampton Ectastic,” for the first time somehow (?) on Gregory Lawless’ blog in an apartment that leaked karaoke at me from all directions late at night. “The chickens I’m to meet in weather unapproachable.” I read this line and crawled out the window with some some raisins shoved in my mouth. I handed my body dumb to the nearest Kimchi pot about to go underground.

4. “My agitated arms grow knotted.

The term to describe this is inextricable.”

-New Revised Standard

The third years in my MFA program recently finished their thesis defenses / presentations. A lot of them wrote about their families. Inevitably, not all of it was / is happy. At every defense, there was some innocuous chatter about whether or not family had attended, whether or not we would have asked our family to come if the thesis being presented was our thesis, if we (the first and second years) were going to invite our family to our defenses. What we would say and what we wouldn’t.

5. “We’re in a giant mom and and dad linked by a heart.

We’re going round in circles in the figure eight”

-Family System

We are galaxy on galaxy on galaxy. (“You think they resemble a galaxy spinning, / but to them you think it’s like being inside two plants / joined at the stalk.”-FS) The last minute of Men in Black is RIGHT. The disorientation of this intimacy of blood. Do we ever know if we are further away or getting closer?

Is it clear to us how we are RELATED to our families exactly? Or is it always changing? My friend, A, sees a picture of my mother and says I look just like her. I reply, “Really?” in a voice that people often mistake for my mother’s on the phone.

“This is the myth of retrospective cohesion.”

-Eight Monks in Unison.

6. “None were flyover people,

nor were they reincarnations, nor stories with beginnings, muddles

and James, who was strangely present, Emma or not,

accepted in that time and place. Vanessa.”

(Marie)

When I turned the book over to see who blurbed, I saw Tomaz Salamun and nodded. I’ve been reading On the Tracks of Wild Game (a wine, a whirlwind) on and off and again and again for maybe six months. I can’t really bear to bring it back to library. Brandon Shimoda wrote a stunning piece at the Volta about Salamun’s blazing use of names in his books. According to Shimoda, Salamun and Christian (according to me) are doing an interesting thing in that they are showing us the systems (the picture of the subdivision from way high up on the front of Family System) surrounding and filling out not just the person, but the “citizen” living a “free country life.”

7. I initially balked at these terms Shimoda chooses to use to talk about Salamun / a poet documenting LIFE. They make me see uniforms a little too tight. They make me feel a little lifeless (life less). However, they’re the right ones (terms from a different way high up / aerial perspective), not only because their part of our first-world reality here in America (and the forgetting we like to do re: what our country is and does to other countries), but because of the way that allows the naming of names to come alive, to rupture us towards richness in spite of the system, which both depletes those names and makes those names possibly networked. There are people here being things / being beings to each other. These are people going beyond the requirements, which breaks the system. It is breaking the system is continually having / failing to adapt to.

8. A Public is a vehicle by which we are transported.”

-A Cataract

9. Here’s Shimoda:

“One characteristic of Tomaž’s work I find fascinating is the constant naming of people—family members, friends, lovers, acquaintances, heroes, poets, artists, politicians, villains—that seems partly not able to be helped: a both conscious and unconscious uttering of names emerging from a true exuberance for being in relation to PEOPLE. Tomaž intones the names of those who populate his poems’ and books’ unfolding free country-life; his intoning, to my ears, anoints the people as both beloved and legend, and within it I begin to hear a nation, or maybe, the dissolution of all nations in the citizens of a free country-life. But they are more than either situational or ecstatic intonations (as if that alone was deficient); they are recollections of the EARTH and the startled, shimmering CLOCK FACES passing upon it…Tomaž makes people PHENOMENAL.”

10. Christian allows the the I of the book to give us a stream of people, mothers and friends and farmers and writers and cousins and peopleIhavenoideawhotheyare hovering in the planet Virginia, that glow PHENOMENAL on the elastic floors of the poems. Where Christian deviates from Salamun lies within the urgency of the tone deployed by the narrating voice. Salamun’s I, in On the Tracks of Wild Game, gives us a dizzy hula hooping afflicted with hives. The voice of Christian’s I exudes a tone that is steadier and absorbent, though perhaps no more or less reliable. “The city came by for the trash. / I found a science of imaginary solutions, which was a good thing” (Responsibility). It is not a voice indifferent to being caught in an orbit of people and place with a poetic tongue, but it accepts or replicates the rhythms and paces of the persistent oscillation orbits have as a way of engaging with observation that pulls the I closer, than backs it away. The steadiness allows the illogical to leak in, to rub, but not roughly. It becomes part of the system, how it perpetuates, but re-forms it into a system that can be unpredictable. READ MORE >

June 20th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

25 Points: The Selected Poems of James Henry

The Selected Poems of James Henry

The Selected Poems of James Henry

by James Henry

Handsel Books, 2002

180 pages / $22.00 buy from Amazon

1. There really is no direct route to Irish poet James Henry (1798- 1876).

2. Most often his fans come by way of Henry James (an absent comma in a library computer) and a well-developed sense of humor.

3. Despite a consistent output (six strong books of poems, beginning in the 1850’s), James Henry was a virtual unknown until the poet Christopher Ricks included him in the 1987 New Oxford Book of Victorian Verse.

4. According to Ricks, the books he found in the Cambridge Library had never been cut. Ricks discovered an enormous treasure in Henry’s work.

5. James Henry shows a hilarious and distinctly modern vision of the world.

6. He champions the prosaic.

7. In one poem he declares, “Blessed be the man who first invented chairs!/ And doubly blessed, the man who beds invented!”

8. In another he celebrates the pleasure of the mattress, “Let those, who will, enjoy the English bed/Of feather-stalks from which successive housemaids/Have pillaged to the last flock of the fine down/…Give me the Italian mattress broad and long/ Of fine, combed wool elastic; and the coarse/Hempen or linen sheets, washed in the fountain.”

9. On his favorite blossoms, “Sweet breathes the hawthorn in the early spring/ And wallflowers petals precious fragrance fling,/Sweet in July blows full the cabbage rose/ And in rich beds the gay carnation glows…But of all odorous sweets I crown thee queen/ Plain, rustic, unpretending, black eyed bean.”

10. Henry was a practicing physician and a student of Virgil. Following his retirement, he traveled Europe, settling in Dresden. This modern cosmopolitanism and his career in medicine both shine through in his strongest works. READ MORE >

June 18th, 2013 / 2:32 pm

25 Points: The Drowned World

The Drowned World

The Drowned World

by J.G. Ballard

Berkley Books, 1962

208 pages / $23.95 buy from Amazon

1. “All the way down the creek, perched in the windows of the office blocks and department stores, the iguanas watched them go past, their hard frozen heads jerking stiffly. They launched themselves in the wake of the cutter, snapping at the insects dislodged from the air-weed and rotting logs, then swam through the windows and clambered up the staircases to their former vantage-points, piled three deep across each other.”

2. Freak extreme sunspot activity melts the polar ice-caps and reshapes the geography of earth. Humanity has migrated to the far north, and the cities of Europe are transformed into lagoons festering with lizards, mould, and ancient plant life. It’s the Triassic, part two.

3. The action focuses on two male biologists cataloguing new species in the lagoon that was once London, and a marooned heiress living in a half-flooded luxury apartment building. The biologists arrive with a military expedition charting the tributaries of the lagoon and surrounding islands. Despite the setting, it’s a boring premise, and it’s a relief when the main body of the expedition returns north.

4. Before the expedition leaves nearly everyone in the lagoon has started to dream about

a pulsing drum beat and “prehistoric sun”, which the biologists determine is a part of

“repressed” primordial memory, dating back to humankind’s earliest verterbrate

ancestors. #is is the main idea of the book. When I %rst got to this part I rolled my

eyes because it’s exactly that idea of “repressed primal drives” that I would expect was

trendy in the 60s and 70s (!e Drowned World was released in 1962). It reminded me

of the movie Wake In Fright, released in 1971, in which a prissy Australian schoolteacher

loses all of his money and basically gets his ass kicked by the Outback.

5. More things the idea of “repressed primal drives” reminded me of: “bogus ‘tribal’ art,”

“shag carpet,” “puma musk,” “gold medallions,” “whiskey,” “leopard print,” “snake

leather,” “open button-up shirts,” “Don Johnson’s alligator in Miami Vice,” “doing a lot

of cocaine,” “desperate misogyny.”

6. In Wake in Fright, the protagonist survives solely on the hospitality of strangers who

get him shitfaced and expect him to fire rifles while shitfaced. The movie is about a lot

of things, and it would be reductive to say otherwise, but contained within its premise

is the idea that there is a monstrous primal animal heart beating in the centre of

everyone. Wake in Fright handles this idea much better than The Drowned World: it’s

far more subtle, for one thing, which I think is partly due to the fact that it’s not

science fiction, although aside from its setting The Drowned World is not particularly

wild or exaggerated. And the Outback in Wake in Fright could almost pass for the

setting of a science fiction movie.

7. Wake in Fright’s excess is the result of despair or boredom whereas in The Drowned

World it is seen as a release or panacea.

8. As a title, !e Drowned World is almost too accurate, ultra-descriptive and relatively

bland, and the text doesn’t really exceed or challenge or stretch its boundaries. I don’t

think a work of fiction has ever delivered as well as The Drowned World does on the

implicit promises its title makes, and yet I’ve never been quite so disappointed. For a

post-apocalyptic wasteland, this was fairly standard fare, except perhaps for sections

like the passage I quoted in the first point.

9. “Drowned world,” “subconscious memories,” I get it, still boring.

10.Science fiction is, of course, always a better indicator of the time in which it is written

than that time’s future, but this book was too often derailed by its insistence on

remaining inside 1960s moral and social codes, as well as that time’s prejudices. This is

the main problem with The Drowned World. READ MORE >

June 13th, 2013 / 12:25 pm

THE ACT OF MEMORY, “LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD” & THE THING OF INTENTION

SUBJECTIVITY OF MEMORY

Suzanne Corkin’s book Permanent Present Tense: The Man with No Memory, and What He Taught the World chronicles the fascinating case of Henry Molaison. Upon receiving a catastrophic lobotomy at the age of 27, Molaison continued his life as an individual incapable of forming new memories. For the remaining 55 years of his life, Molaison was closely studied by Corkin: his unique tragic circumstances constituted him as a one of a kind empirical specimen of anterograde amnesia, the medical term for his inability of forming new memories. Corkin found in him the ideal means to gain a deeper scientific understanding in the field of neuroscience[1].

Unlike the Drew Barrymore character in 50 First Dates, Molaison spent his amnesic reality in the company of a meticulous observer and not the romantic goofiness of Adam Sandler. The focus of Corkin’s book is the scientific exploration of how new memories are cerebrally processed. Corkin observed the short-span consciousness of Molaison’s new memories along with the variation of the feelings and thoughts he exhibited, as everyday provided a new opportunity to reassess her specimen all over, evaluate and reevaluate the pertinent data. Despite the repetitive occurrence of the same questions within his short-span of memory, Molaison’s responses were sometimes indicative of the formation of new memories. This analysis served as a catalyst for a new neuroscientific theory: contrary to previous popular belief that memories “were indelible snapshots of sense experience, stored in chronological sequence like the frames of a celluloid film,” memories are actually located in more than one location in our brains.

Mike Jay’s exceptional review of Corkin’s book[2], aptly entitled “Argument with Myself,” starts with a powerful definition of memory. Jay concedes that memory shapes one’s identity, but he argues that in addition it simultaneously functions as the (mis)apprehension of a well-founded, whole self: “memory is not a thing but an act that alters and rearranges even as it retrieves.” In this framework, it is evident that the way we conceive our individual realities, as they are constructed by all the memories we hold, are suspect. The manner in which all of us accentuate the details of what happens, both to us and in the world surrounding us is marked by subjectivity. While the degrees of each person’s paranoia and tendency for narrative exaggeration vary, there is no doubt that in most “realities” much is not real.

In an endeavor to make her students grasp this very fact, Mary Karr once began teaching a creative writing course by performing getting in a huge spat with the educational institution’s program director[3]. Once the program director exited, Karr revealed to her students the argument they had witnessed was a simulation. She then asked them to write down their observations and perception of the incident. The students had an arduous time reaching consensus on a collectively agreed objective account of what had just happened in their classroom. This exercise swiftly presents the validity of the very ambivalent nature of objective memories.

25 Points: alphabet

alphabet

alphabet

by Inger Christensen

New Directions, 2001

64 pages / $12.95 buy from Amazon

0. Inger Christensen—that petite, Danish demigod with her propensity for potted plants and the wild unknown—must have been hounded by the idea of growth. By what is massive. I guess if you look at/dwell on the vastness of things for long enough, you’ll predictably find yourself engaged with death options, the tempered dark where there are no underthings to stabilize you—and you are a little dust, alone with the chilling and the growing of yourself. It’s just you you you and the big outside.

1. Christensen’s alphabet is a sprawling network, shaped by the Fibonacci sequence that signifies nature’s inclination toward animal, exponential levels of growth and similar vanishings of decline. There’s an incantation stitching the poem, especially its beginning, that simply verifies the existence of things:

killers exist, and doves, and doves;

haze, dioxin, and days; days

exist, days and death; and poems

exist; poems, days, death

Death exists, details exist, the small monotony of days exist, all alongside one another.

1. I once read the entirety of alphabet in one of those concrete courtyards, the sad kind that’s trying to cute-up a hospital. I read it another time out loud for someone (although finishing was weird and uncomfortable because I was just beginning to tell, although I liked this person at the time, that they were not really interested in me and definitely not interested in 80-page metaphysical poems structured like the Fibonacci sequence), and another time on my bedroom floor with a whole .75 of OT that was looking nothing like a group sport because I was sad about something or something. And many times before and after that I can’t remember anymore. One magical person said, when I asked her about alphabet, that it made her think about cornfields a lot.

2. I sometimes try to relate my deep affection and appreciation for the state of Iowa, and I always think about cornfields that continue past the curvature of the earth, this massive output of production that literally exceeds our capacity to see it, much less understand it. “wheat in wheatfields exists, the head-spinning / horizontal knowledge of wheatfields, half-lives, / famine, and honey . . .”

3. Sometimes all it takes to be humbled is just the existence of certain things.

5. I’m shocked and quieted every time I read a newspaper, but not like I am by cornfields or incomprehensibly vast networks of connection. Although, the more I think about alphabet and re-live those declarations of both physical and metaphysical existences, the less I see the distinction.

8. There are some lines in there that simply state the death count for some great tragedies— “140,000 dead and / wounded in Hiroshima / some 60,000 dead and / wounded in Nagasaki”— and these numbers stand still on the page. The lines are always wavering between the porous and the immovable, the intimate and the intergalactic.

13. I wonder what it would look like, speaking of networks of connection, if Christensen had written a long poem/book of poems about the internet. Like, would that be beautiful? Would that be sheer terror?

21. It’s impossible not to talk about Susanna Nied’s translation. In an interview at Circumference last year, Neid said that she started working on alphabet’s translation in secret: “I didn’t tell Inger I was doing it. For the time being, I didn’t want anyone else’s input, not even hers. I had a very strong sense of what the poems could become in English. I kept shaping and reworking. Interlinked sprials. Double helix. Beauty and destruction. I was possessed.”

34. You can easily be possessed by Christensen. If you hear alphabet being read aloud, the words bend towards rapture, like hypnotism. Partly due to the steadily revolving repetitions—existence, vanishing, existence, vanishing. READ MORE >

June 11th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

25 Points: Regard (25 parentheticals)

Regard

Regard

by Pablo D’Stair

KUBOA, 2013

280 pages / $7.50 buy from Amazon

1. (all of blue)

2. (having to dig it out of the soil at the base of one of the tree trunks)

3. (of what variety she couldn’t quite make out in the dim lighting)

4. (tipped out of its holder)

5. (transparent yellow with the appearance of bubbles throughout it)

6. (interested that the hole proceeded more straight down than she’d thought it was going to)

7. (she couldn’t seem to settle the question in her mind if this was the usual way of things)

8. (she leaned against not very often)

9. (like the man had in imitation of the dog)

10. (not loudly, but not self-consciously enough to be whispering) READ MORE >

June 4th, 2013 / 3:11 pm

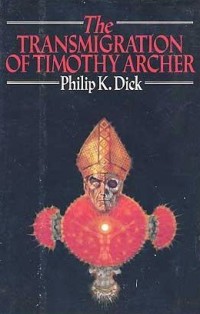

25 Points: The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

by Philip K. Dick

Mariner Books, 1982

256 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

1. If Phil Dick were a preacher, I think there would be a lot more interest in religion with his unique blend of fantasy, science fiction, philosophical speculation, ontological conundrums, and church history.

2. I bought the Transmigration of Timothy Archer at a bookstore called the Last Bookstore which gave me an ominous reminder of the apocalypse, or perhaps just the end of paperback books. When I studied the history of Christianity at Berkeley, I was surprised to find out that in the year 999, people were convinced the end of the world would come on 1000 and mass hysteria spread across the world. 1000 came and went and the world is still here.

3. The character of Bishop Timothy Archer is based on a real life American Episcopal bishop named James Pike who was friends with Philip K. Dick. Bishop Pike lived from 1913-1969 and led a huge congregation at the Grace Cathedral. He was a controversial figure who supported the ordination of women, racial desegregation, and the acceptance of LGBT people. He worked in support of civil rights and marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. during his march to Selma, Alabama. He was an alcoholic, had a romantic relationship with his secretary, and was brought up on heresy charges multiple times for questioning the virgin birth and the existence of Hell. He was never convicted.

4. The Transmigration of Timothy Archer is the third book in a trilogy that includes VALIS and the Divine Invasion. You don’t need to read the first two to understand this one, though it helps. This one also has no science fiction elements in contrast to the previous two.

5. The book starts with the death of John Lennon and is told through the perspective of Angel Archer who is the daughter-in-law of Timothy Archer. Timothy Archer is already dead and she is reflecting back on his life and the fact that he sought “what lies behind Jesus: the real truth. Had he been content with the phony, he would still be alive.” He begins to question the identity of Jesus after learning about the discovery of the Zadokite Scriptures, now known as the Damascus Scriptures. In those scriptures predating Christ by two centuries, there are references to sayings Jesus made, suggesting the message was not entirely original. It’s those implications that drive Archer on his quest.

6. To be more specific: “My point is that if the Logia predate Jesus by two hundred years, then the Gospels are suspect, and if the Gospels are suspect, we have no evidence that Jesus was God, very God, God Incarnate, and therefore the basis of our religion is gone. Jesus simply becomes a teacher representing a particular Jewish sect that ate and drank some kind of— well, whatever it was, the anokhi, and it made them immortal.”

7. Anokhi means Pure Self-Awareness and was eaten at the Messianic banquet. The Last Supper Jesus had with His disciples wasn’t just a sharing of bread and wine, but in a parallel with Zoroastrianism and Brahman, an assimilation and unification with God.

8. Timothy Archer refers to John Allegro, the official translator of the Qumran Scrolls, who posited a theory in his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. That theory was that Jesus and His early disciples smoked mushrooms that gave them hallucinations and became the basis of their religion.

9. Jeff Archer, Bishop Archer’s son and Angel’s husband, has his own theories. He is particularly obsessed with the idea that “the ills of modern Europe” can be traced “back to the Thirty Years War which had devastated Germany, caused the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire, and culminated in the rise of Nazism and Hitler’s Third Reich.” A prominent figure in those times was the German general, Wallenstein, who “colluded with fate to bring on his own demise. This would be for the German Romantics the greatest sin of all, to collude with fate, fate regarded as doom.” Jeff Archer ends up committing suicide after he falls in love with the woman Timothy Archer is sleeping with.

10. Timothy Archer is sleeping with his secretary, Kirsten. READ MORE >

May 30th, 2013 / 12:18 pm