25 Points: His Master’s Voice

|

His Master’s Voice

by Stanislaw Lem

Northwestern University Press, 1999

199 pages / $16.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. I first read Stanislaw Lem after seeing an anonymous review of The Cyberiad on HTMLGIANT.

2. I’ve read two of his books. A year or two ago I read Solaris, then last week I read His Master’s Voice.

3. His Master’s Voice, published 7 years after Solaris, echoes the earlier book in pleasing ways. The most obvious to me was that neither ever directly answers the mystery near the heart of each book. A reader will not definitively learn the nature of the ocean on Solaris, or what the letter from the stars says.

4. HMV places human failure more centrally than Solaris. The narrator of HMV, Peter Hogarth, is (after the fact) a complete pessimist about humanity’s time facing their impossible task.

5. The book is philosophical, often profound. For example: “Our ability to adapt and therefore to accept everything is one of our greatest dangers. Creatures that are completely flexible, changeable, can have no fixed morality.”

6. Or, “Psychoanalytic doctrine reveals the pig in man, a pig saddled with a conscience; the disastrous result is that the pig is uncomfortable beneath that pious rider, and the rider fares no better in the situation, since his endeavor is not only to tame the pig but also to render it invisible.” Hogarth does not have much love for psychoanalysis throughout the book.

7. Lem would eventually focus most of his effort on writing philosophical essays and abandon the novel. Knowing this made it hard to separate Lem and Hogarth during these tangents.

8. Something I find particularly engaging about Lem’s writing is his way of introducing the reader to complex scientific and technological ideas on which he was likely not an actual expert, and doing so with authority. I’ll come back to this.

9. At one point in the book Lem uses Hogarth and another of his characters as mouthpieces for his own personal views of pulp science fiction. Lem was famously not a fan of most of his contemporary genre writers, and when the character Rappaport hits a wall in his research he resorts to reading a stack of apparently mediocre SF—“expecting variety, finding monotony.”

10. One of several reasons Lem gave for no longer writing fiction was his inability to keep up with the increasing number of papers being written on the cutting edge of science. This meant that he could no longer keep writing books involving cutting edge ideas with the sense of authority I earlier admired. Maybe he feared that without that he would be just another indistinguishable pulp science fiction author.

July 3rd, 2014 / 12:00 pm

25 Points: The Fun We’ve Had

|

The Fun We’ve Had

by Michael J. Seidlinger

Lazy Fascist Press, 2014

168 pages / $11.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. I want the cover of this book framed and hung up in my room.

2. Recognized and accepted that this novel was going to end in tragedy from the beginning.

3. They either brought a really shitty oar on this terrifying adventure, or that guy doesn’t know how to paddle. (It breaks within the first few pages.)

4. Life lesson from this novel: coffins don’t make good boats. (No shit.)

5. Imagined this book as one of the little “skits” in the film Heavy Metal with “Fade to Black” by Metallic playing in the background.

6. After realizing that Seidlinger was using the five stages of grief as a plot device, I immediately thought of a Robot Chicken skit where a giraffe gets stuck in a sand pit.

7. The Fun We’ve Had is an extreme form of marital counseling.

8. How the hell did these people get into this situation? (This can be taken as both a literal and metaphorical question.)

9. I want to know what ocean these people are sailing through—and don’t tell me it’s the “sea of life” because that’s bullshit and you know it.

10. Seidlinger doesn’t believe in long paragraphs. He wants to jab you with short one-liners that make you question everything.

July 1st, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Hustle by David Tomas Martinez

Hustle

Hustle

by David Tomas Martinez

Sarabande Books, May 2014

84 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon or Sarabande Books

Hustle, David Tomas Martinez’s debut book of poetry, is a cry from the street written with developed-over-time, intelligent style with pace the and moxie of a tom cat. The opening poem, placed even before the table of contents and dedication, “On Palomar Mountain” establishes a theme that will carry its way throughout this four part collection of poems as it begins, “The dark peoples things//for keys, coins, pencils / and pens our pockets grieve.” Those three things their pockets lack are the book’s foundation. Keys, coins, pencils and pens tell a story with nothing but “a lighter for a flashlight” that is begging to be told. It is the story of the bold but shed in a sensitive light as the poem ends with a “walk into the side of a Sunday night.”

While fairytale readers and romantic poets might object to Hustle’s style, those with their boots sunk deep in urban black-top pavement will resonated with the jazzy, up-beat rhythm of Martinez’s lines. Lines chopped short and neat with stanzas generally organized into few line bunches compliment the underlying sentiments of the words as the narrator (presumably Martinez himself) declares ownership of what is to be presented in the opening poem of section one:

A car want to be stolen,

the night desires to be revved,

will leave the door unlocked,

a key in the wheel well

or designedly dropped from a visor.

A window will always wink

to be broken by bits of spark plug

or jimmied down the glass.

This is mine.

Where is the window to break

Iin your life?…

Literally inviting the reader to break into the life of the story, Martinez teaches the reader to hot-wire, jimmy-rig, and break an entry into the rest of the book. Clearly, the man in in possession of a story that needs to be told. Have no doubts about it, this is Martinez’s own story. Collectively, the poems become a memoir, highlighting details of the poet’s life which some might find shocking coming from a well-spoken, educated individual.

To tell his story, Martinez organizes the book into four sections. In sections one and two, he continues with the themes that have been established in the beginning of the book while incorporating the facets of growing up ruff which are often overlooked. The importance of a (dis)functional family life, for example, is first mentioned in part II of “Calaveras”

Yes, families are supposed to be circuses.

Accept is, and accept that the acrobat’s taffy

of satin will twirl, and the bears in tutus will spin

over the exposes in the warped wood

and cracks in the waxy linoleum,

all the while your grandfather will yell

“You no like it, go in the canyon and eat tomatoes.”

June 30th, 2014 / 10:00 am

I HAVE TO TELL YOU by Victoria Hetherington

I HAVE TO TELL YOU

I HAVE TO TELL YOU

by Victoria Hetherington

0s&1s, June 2014

151 pages / $6 Electronic. Buy from 0s&1s

There’s a questionably selected excerpt from Victoria Hetherington’s I Have to Tell You available as a preview. It’s from the point of view of a college woman sitting around smoking weed with friends. Written with great veracity, this is as interesting as being the sober listener of a high college student retelling in detail her conversations (not very). Only when the excerpt culminates in the woman’s reflections—

—is the writing characteristic of Hetherington’s excellent first novel as whole: graceful and poignant, often redolent of Annie Dillard’s sparing prose rising to beautiful abstractions, open to the everyday’s influence on personal narratives.

I Have to Tell You is a catalog of pain splintered into multiple characters’ points of view in chronological episodes. Their story is told predominantly through first-person narration, but also through shorthand journal entries, emails, and google searches. It is a litany of voices trying to understand and rationalize their pain to themselves. Some may be put off by this agonizing, but it is not facile, solipsistic, or ironic agonizing—it is instead Socratic, a desperate dialogue with hurt, loss, impending death, and the social devaluation of aging. But all this pain talk is not to say Hetherington isn’t funny or clever, which she often is; writing about pain in fiction often benefits from humor, especially when it’s the pain of white middle-class Torontonians.

Hetherington’s characters indulge in their suffering, which becomes an act of resistance to what creates suffering. Cocaine abuse, erotic desire incommensurable with politics or friendship, an aging woman who gets plastic surgery because she sees in her own reflection the face an acquaintance makes at the moment of death; these self-destructions are resistances, announcements of the pain that goes hand-in-hand with living fully in the world. Their experience of misery is reminiscent of an old saying of Chinese criminals about to be put to death: “In twenty years I will be another stout young fellow”. It’s a proud act that challenges suffering by embracing it scornfully, acknowledging its cyclical pervasiveness.

Suffering in I Have to Tell You also recalls the Western biblical mythos surrounding gender and reproductive organs. Menstruation as God’s punishment is the biblical explanation of a biological phenomenon present before the Bible. Circumcision is a covenant God makes with men in order to arrange for divine dominance of their reproduction. One is an explanation. The other is a prescription. Here, women are punished simply by existing and must find meaning in light of this. Men are made to suffer (or subscribe to suffering) in the name of meaning, for some supposed higher and vaunted power. Similarly, men in I Have to Tell You see their suffering as a cosmic agreement in order to secure some noble identity. This is the case for a character who ascetically and sentimentally makes the woods his home as he prepares for death. Conversely, women are made to suffer merely by existing; they seek a way of explaining and living within the pain from which, being that of culture and stemming as far back as childhood trauma (as in one character’s teenage “relationship” with a strange abusive older man), they cannot escape but can perhaps revolt against. This is not to say the book has an uncomplicated rift between how different people experience pain; everyone, of course, experiences pain and everyone experiences it differently. But the distinctions Hetherington draws between the attitude and culture that surrounds male and female pain in I Have to Tell You, even the self-proclaimed feminist men (who, we see through one character’s specious arguments, still just don’t “get it”), rings true.

Despite their shortcomings, Hetherington respects her characters with an unassuming commitment to unironic truthfulness, showing great proficiency for writing in different voices that speak through a variety of media, woven together with beauty and coherence. The inclusions of technology lack clumsiness or forced cleverness; it’s an organic outgrowth of her characters’ natural assertions or understandings of identity. If there ever is a “Great American Novel” (a probably stupid concept) this is how it should look—but of course it’s Canadian.

***

Joe Hogle lives in Pittsburgh, PA. He is also known as poopsmithey, Ronny Cammareri, and ~LEATHA WHIP~. You can read a hypertext story and some of his poetry here.

June 27th, 2014 / 10:00 am

25 Points: Black Cloud

|

Black Cloud

by Juliet Escoria

Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2014

144 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. Juliet Escoria, as a writer, is like a birthday present you didn’t expect to get but secretly hoped you would.

2. It’s hard to pick a “favorite” from Black Cloud—but my top three would probably be “Heroin Story”, “Reduction”, and “I Do Not Question It”.

3. I feel like I know all of Escoria’s characters. I empathize with them. I care about them. I want to fuck up all the shit that made them miserable because, to me, they deserve better.

4. There are stories within these stories—little hints into the lives of these characters that stick with you.

5. Playlist for this book: Gary Jules’ version of “Mad World” on repeat.

6. Feel like Escoria is a new-age Bukowski but is extremely new and original at the same time.

7. These stories seem so real that I can’t decide if Escoria actually lived through all this or not. (Probably took experiences from her own life to build around these stories—that’s obvious—but I’m more so troubled with the idea that her life has been that awful thus far.)

8. Declaration: Black Cloud is the best work produced by a new, young writer this year and I challenge anyone to top it. (Spoilers: you won’t.)

9. Black Cloud makes you realize how good your life is.

10. Sadly, a lot of Generation Y can relate to the absence of fathers in this story collection.

June 26th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Lucas de Lima’s Wet Land

Wet Land

Wet Land

by Lucas de Lima

Action Books, March 2014

108 pages / $12-16 Buy from Action Books or SPD

The premise of Wet Land is almost impossibly weird: it’s a book-length response to the death of Lucas de Lima’s close friend Ana Maria, who was killed by an alligator. Written mostly in all-caps, the poems are delivered by a narrator who frequently takes the form of a bird, ruminating on Ana Maria, the gator, and the act of writing itself. Early on in the collection, de Lima describes the act of watching a televised reenactment of Ana Maria’s death: “IN THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC DOCUMENTARY THE ACTRESS LOOKS/NOTHING LIKE ANA MARIA;/THE OTHER ACTRESS LOOKS NOTHING LIKE HER FRIEND.” Here, de Lima sets the tone for many of the tensions that characterize this collection. It’s easy to criticize this kind of tasteless reenactment—to see it as a byproduct of a violent, media-obsessed culture. But in Wet Land, de Lima turns the lens on himself, exploring his own anxiety about being complicit in the reappropriation of tragedy.

June 23rd, 2014 / 10:00 am

Inclusion in Ed Steck’s The Garden

The Garden

The Garden

by Ed Steck

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2013

104 pages / $14 Buy from UDP

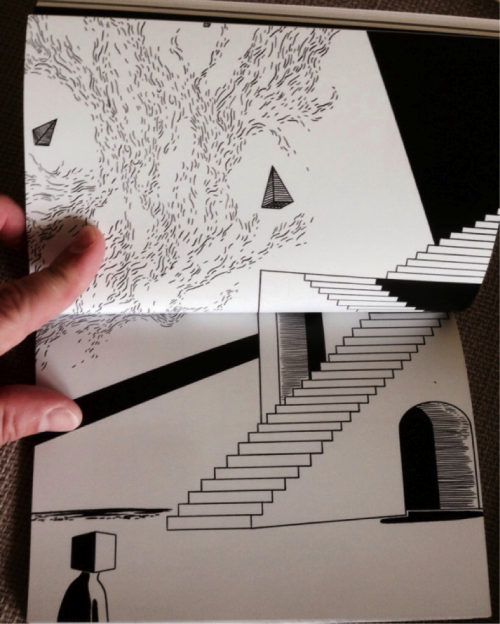

If the Romantic model of the garden is cultivation, then the Post-War model is invasion. Robert Duncan inquires of that famous, primordial garden, “is it dream or memory? homeland of the pleasure principle in the libidinal sea, an island girt round with forbidding walls?”[1] And of ornamentation, William Carlos Williams reminds us “that the bomb also is a flower.”[2] The multiflorous gardens of Ronald Johnson abstract whole histories for admission into their horticultural field. Rampancy, tended by besieged consciousnesses, overruns “the old garden-ground of boyish days.”[3]

The degradation of idealized forms is, of course, a hallmark of post-modernism, but the temptation of placing the world within the garden, or enlarging one’s garden infinitely, enacts a dialogue of control and ownership that becomes problematic for any anti-imperialistic project. Similarly, there is the risk of oversimplification that an artist runs when attempting to account for the volume of media produced around the event of war. Ed Steck’s The Garden: Synthetic Environment for Analysis and Simulation, published by Ugly Duckling Presse, continues the erosion of privileged space begun midcentury with an all-important newness equipped to navigate the bizarre landscape of the 21st.

June 23rd, 2014 / 10:00 am

The Inevitable June by Bob Schofield

The Inevitable June

The Inevitable June

by Bob Schofield

theNewerYork Press, June 2014

144 pages / $20 Buy from theNewerYork

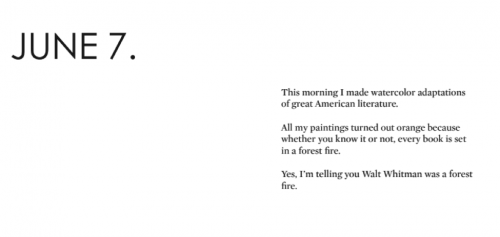

I think a lot about the color orange, and also about new ways of naming.

From The Inevitable June. Image courtesy of biblioklept.

Frank O’Hara thinks about orange one day. He writes pages and pages of poetry. He says in Why I am Not a Painter that “There should be / so much more, not of orange, of / words, of how terrible orange is / and life.”

From The Inevitable June. Image courtesy of theNewerYork.

Both Schofield and O’Hara seem correct about orange. But, as his relationship to orange is meant to show, O’Hara is not a painter. Whatever you want to call The Inevitable June in terms of genre (who cares?), it’s heavy on the visual, so orange for Schofield and his narrator doesn’t serve as a line in the sand, stifling or sidestepping the visual. Instead, orange is simply something discovered to be inevitable, much like the inevitability of the old woman who kisses the narrator on the cheek on June 6. Even as ‘every book’ might not seem orange, adapting any given book to watercolor will ‘reveal’ its inevitable orangeness.

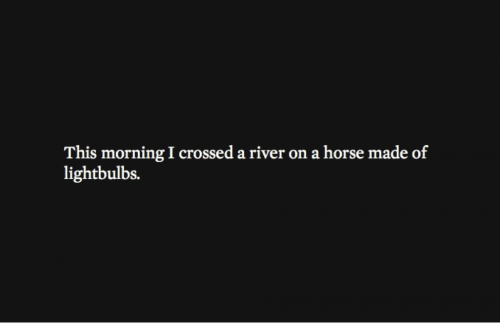

This is important, I feel: the indeterminacy or withdrawnness of Schofield’s language is anchored to the irrevocability of the narrative arc. What happens in it is what happens, both contingent and unavoidable, and the language coils around this anchor in something resembling play, or discovery, but not of anything. More a disembodied feeling whose color the reader inevitably wants to name. The visual element also explores this tension, serving both as a clean, minimal ground for the flight of imagery as well as sometimes ‘phasing’ into inscrutability with respect to its relation to the words.

from The Inevitable June. Image courtesy of biblioklept.

June 20th, 2014 / 10:00 am

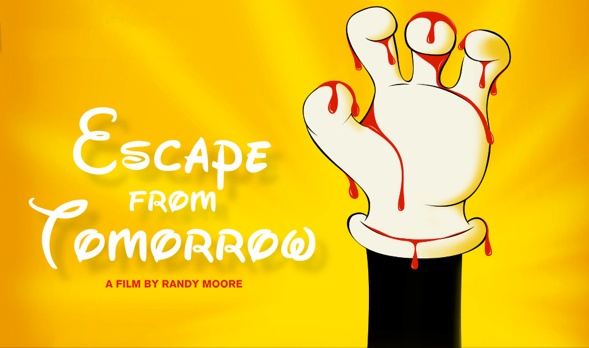

25 Points: Escape from Tomorrow

1. This movie stuck it to the man by filming the entire production in both Disneyland and Disney World without their permission.

2. Disney is apparently “aware” of this movie but has taken no legal action.

3. I’d never heard of this film until a friend forced me to watch it. I neither regret this nor thank him for it.

4. This film somehow succeeded in making Disney a terrifying menace that is a threat to fathers everywhere.

5. “What the fuck am I watching?” is what I thought multiple times while viewing this film.

6. Pedophilia is everywhere in Disney. Fathers chase after underage French girls, retired Disney princesses kidnap little kids to reenact scenes from Snow White, little boys are shown pictures of naked foreign women during cinematic rides—the list goes on and on.

7. Can’t help but be paranoid that Disney will sue me over this review. I have nothing, you bastards.

8. The film opened with someone being decapitated on a Disney ride—then cut to a scene of a corporate asshole firing the protagonist over the phone while he was on vacation with his family. The scary part is that both of these incidents have occurred multiple times throughout the course of modern human history. This makes me dread graduating college and entering the real world.

9. My friend and I both agreed that the protagonist’s wife was a bitch the entire film. (Spoilers: she sadly doesn’t die.)

10. There’s a scene where a nurse suddenly breaks into tears and I still don’t understand why.

June 19th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

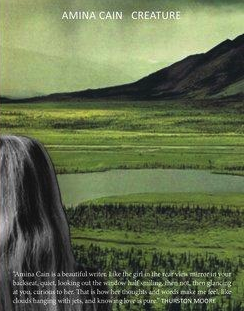

I write to see what is inside my mind: An Interview with Amina Cain

“I’m not sure why I’ve written so many flat male characters. I think it’s more that I have wanted to pay attention to the female characters and so I have.”

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

***

LW: When did you start writing?

AC: I began writing during my last year of college. I started out as an acting major, which I quickly gave up, switching to Women’s Studies. I knew I wouldn’t necessarily do anything specific with this major, but I was interested in the classes. Then, when I took my first creative writing workshop, I knew I had found what I wanted to do with my life.

from the film adaptation of Hour of the Star

There are many references to Clarice Lispector in your work and in your story Queen you quote from The Hour of The Star: “forgive me if I add something more about myself since my identity is not very clear, and when I write I find that I possess a destiny. Who has not asked himself at one time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?” When did you first discover Clarice Lispector? Would you say you connect similarly to her themes of the metaphysical experience of “finding yourself” through the process of writing?

I relate very much to the idea of finding oneself through writing, though what “oneself” is I think is malleable. And that Buddhist idea that to study the self is to find the self and to find the self is to lose the self resonates a lot for me. I’ve been curious lately about why I am so driven to write first person narratives (that are both not me and me) as opposed to third person, for instance. It’s not that I want to tell a story of myself, or even of another, it’s that I want to inhabit something—some feeling, some space (physical or psychic, and yes, even just the space of writing), or voice, and the first person, for whatever reasons, allows me to do this in the strongest way. I certainly think that Lispector’s fiction does this too, much more so than simply telling a story. She creates these charged psychic spaces we can walk into as readers. I first read Lispector the second time I lived in Chicago. I checked out from the library Family Ties, a collection of short stories. Then The Hour of the Star.

So many of your stories seem to be about a central narrator. They can be separate and yet they feel a part of a continuous story. Can you talk about the narrator of your stories? Do you consider her a persona? Do you see her as existing in each of your stories? Or is she different, a new character, each time?

I see the narrators in Creature as different beings but as sharing a single heartbeat. I wanted them to be both separate and connected. In Tisa Bryant’s amazing Unexplained Presence a beautiful continuum comes into being, or else a soft light is shone on connections already present between people who existed throughout time but never knew each other, or even knew to know each other. I was so struck by that when I first read Bryant’s book, and I think the idea of the continuum has stayed with me since, though of course in a different way.

There is a quality of bleakness to your characters, or to quote from one of your titles, “a threadless way” about them. They are very honest about the fact that they don’t know what they are doing or how to connect to others. (And yet, because of this, they do know—like what you were saying about finding the self to lose the self, etc.)

This is a sharp contrast to what we are used to seeing in a lot of contemporary literature. (Of course, “flawed characters” are everywhere—but usually they don’t know they are flawed and when they do, their revelation is fleeting or they step into denial.) Your characters have the ability to speak, feel, and live out their insecurities, distastes, annoyances, melancholy, and this gives them a strange hopefulness and positivity.

I think that most of my characters are searching for something, are always in process with the world around them, and that much of what gets expressed in the stories are the things that are usually not said, supposed to be said, voiced. In fiction, I’m as interested in an inner life as an outer one, and I want to write that life. I think it can propel a narrative forward as much as plot can. There is drama there, and conflict, and relationship, and even setting. I’m glad that the characters feel hopeful to you. Sometimes there is a focus on the sadness and vulnerability in my stories, elements that are certainly present, but to me there is also absurdity and humor. READ MORE >