Music

In memory of Robert Ashley, 1930–2014

I first learned about Robert Ashley through Peter Greenaway, thanks to his Four American Composers series. I rented all four videos because I was interested in John Cage and Philip Glass. I didn’t know who Meredith Monk was, or Robert Ashley.

As it turns out, the episode on Ashley interested me the most. I didn’t understand the opera being discussed, Perfect Lives, but I knew I had to hear and watch the whole thing. I took to the internet and discovered that I could order it directly from Lovely Music, on VHS. I did so. It cost me $100—but I had to hear it.

Few people I knew at the time had ever heard of Robert Ashley. When I moved to Illinois and met Mark Tardi and Jeremy M. Davies, we bonded in part over our shared love for Perfect Lives, “an opera for television” made in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It’s still not widely known. It’s still never been broadcast in its entirety in the US. But I’m not alone alone in regarding it one of the greatest operas and long poems in the English language. (John Cage wrote of it: “What about the Bible? And the Koran? It doesn’t matter. We have Perfect Lives.”)

Perfect Lives is set in a small anonymous Midwestern town: “These are songs about the Corn Belt, and some of the people in it—or, on it.” (There are synopses of the opera’s exquisitely dizzying plot here and here—they read like something out of Gaddis, or Pynchon.) When I lived in Bloomington-Normal, IL, I took a lot of pleasure in imagining that the whole elaborate thing was set there, and was still taking place there—that I might at any minute happen upon Gwyn and Ed (the eloping lovers), “D” (“the captain of the football team”), bank robbers Raoul de Noget and Buddy (“the world’s greatest piano player”), Eleanor (who later got her own opera), and above all else, Isolde, who stands in the doorway of her mother’s house, staring into the backyard and meditating on time:

She thinks about her father’s age.

She does the calculations one more time.

She remembers sixty-two.

Thirty and some number is sixty-two.

And that number with ten is forty-two.

She remembers forty-two.

“Remembers” is the wrong word.

She dwells on forty-two.

She turns and faces it.

She watches.

She studies it.

It is the key.

The mystery of the balances is there.

The masonic secret lies there.

The church forbids its angels entry there.

The gypsies camp there.

Blood is exchanged there.

Mothers weep there.

It is night there.

Thirty and some number is sixty-two,

And that number with ten is forty-two.

That number translates now to then.

That number is the answer, in the way that numbers answer.

That simple notion, a coincidence among coincidences, is all one needs to know.

My mind turns to my breath.

My mind watches my breath.

My mind turns and watches my breath.

My mind turns and faces my breath.

My mind faces my breath.

My mind studies my breath.

My mind sees every aspect of the beauty of my breath.

My mind watches my breath soothing itself.

My mind sees every part of my breath.

My breath is not indifferent to itself.

Those lyrics come from the seventh and final part of the opera, “The Backyard (T’Be Continued),” which remains one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard. For the past ten years, I’ve been setting aside a day each year just to rewatch and listen to the opera, then transcribe “The Backyard.” I don’t do this with any other opera, not even other favorites, like Einstein on the Beach or The Magic Flute. And I’ve occasionally thought, “When I die, maybe I’ll request that people listen to this in lieu of holding a funeral.” I have to wonder what my loved ones would make of it: John Sanborn’s video art, “Blue Gene” Tyranny’s piano and synthesizer lines. The kooky drum machine! David van Tieghem and Jill Kroesen’s deliciously punk-like, slack performances.

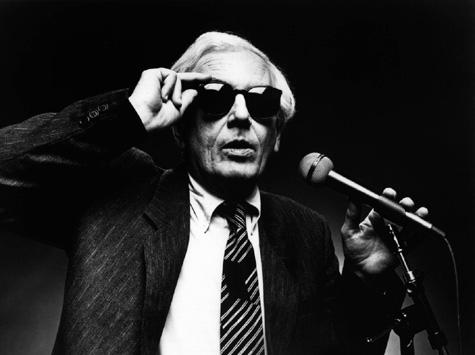

And drifting above and through it all, Robert Ashley’s calm, hypnotic voice. Sometimes when I’m trying to explain the man’s work to people, I call him a talking poet, similar to Laurie Anderson and Spalding Gray and David Antin. Or even a stranger Garrison Keillor—one who’d wear glitter and shades and speak-sing about the Midwest (he was from Michigan) while standing next to neon lights. I’ve practiced imitating his voice, which I adore and could listen to forever.

Jeremy emailed me late yesterday with a single swear word and a link to a post by Kyle Gann, announcing Ashley’s passing. Since then, there’s been a flurry of discussion about the man online. I wanted to add my own small voice to that because, for fifteen years now, Ashley has been one of my favorite artists.

He composed a lot of music and I’m still working my way through it, discovering the depth and breadth of his genius. Much of it has long been out of print, though more of it is becoming available now. The past four years in particular have seen something of a sea change. Dalkey reprinted the libretto of Perfect Lives, accompanied by an excellent essay by Kyle Gann, who published a biography of Ashley. Atalanta was reissued by Lovely Music (and even got reviewed at Pitchfork, of all places), and the libretto came out through Burning Books. There were retrospectives and new performances, including a day dedicated to recreating Perfect Lives in Manhattan. Not to mention more work by Ashley himself: Concrete, Quicksand, Mixed Blessings.

The internet has helped some, as more and more work winds up online. I hope that hasn’t hurt Lovely Music any; instead, I like to think that YouTube and UBUWEB have made Ashley’s work more accessible, more widely-known. Thanks to the internet, I got to see some of the TV series that Ashley once made, Music with Roots in the Aether, a kind of talk-show where he spoke for hours with David Behrman, Philip Glass, Alvin Lucier, Gordon Mumma, Pauline Oliveros, and Terry Riley. I’m especially fond of the Alvin Lucier episode: he and Ashley wear fishing gear and cast contact mics about by means of fishing poles. It’s like the greatest episode of Fishing with John never made (apologies, Mr. Lurie). (The whole series is available on VHS through Lovely Music.)

I got to speak with Ashley only once, when Jeremy and I interviewed him. He was wonderfully humble, funny, and gracious. The last paragraph stands out now:

I am blessed with good health, but of course that’s “relative.” Anecdote: fifteen minutes after I “knew” that I had just finished an opera libretto called “Celestial Excursions” (and had drunk all day about 20 cups of tea) and I was supremely happy, I had a heart attack of a sort (atrial fibrillation). The doctor said, “Age, stress and caffeine.” That was bad news. I really liked caffeine. But otherwise physical has no meaning, except that I am getting older and less strong.

So, too, does the opening of the second episode of Perfect Lives, “The Supermarket (Famous People)”:

This song is dedicated to Maurice de Sutter. The motto is, “Well, it can’t hurt.” The interpretation is: Maurice is pretty old by doctor’s standards. Actually, he’s pretty old by anybody’s standards. And he’s reached a kind of perfection. I mean, the success of his life as a farmer, and the success of his family, and their gentleness and generosity, has created around him a kind of … heaven. It’s obvious when you’re with him that he’s in heaven. So he really has only one problem left: the transition between this heaven on Earth, to whatever the structure of the next one will be—the moment, in other words. And if I could presume to describe the largeness of his spirit in the contemplation of that moment, I always imagine him saying, “Well, can’t hurt.” These are songs about the Corn Belt, and some of the people in it—or, on it.

Speaking from the Corn Belt, Mr. Ashley, this is me saying godspeed, and thanks.

Tags: alvin lucier, burning books, Dalkey Archive Press, David Antin, David Behrman, garrison keillor, Gordon Mumma, jeremy m. davies, John Cage, Kyle Gann, laurie anderson, Lovely Music, Mark Tardi, Meredith Monk, Mike Powell, Pauline Oliveros, Peter Greenaway, Philip Glass, Robert Ashley, Spalding Gray, Terry Riley

Sad news, indeed; makes you want to go somewhere dark and just listen to his voice. Thank you for pulling all this detail together in once place, AD.

Maybe fall asleep on a hot summer afternoon listening to “Automatic Writing” on headphones…

i’d seen a couple greenaway movies a few years ago, so when i saw your mention of Four American Composers, i got it with the same state of awareness (interested in cage/glass, not knowing monk/ashley), so i look forward to those with another reason now.

[…] Robert Ashley […]