25 Points: Gerald McClellan vs Nigel Benn

Gerald McClellan vs Nigel Benn

Gerald McClellan vs Nigel Benn

by Sam Pink

Wormblanket Press, 2013

$10.00 buy from Wormblanket Press

1. Who are these people. I picture Gerald McClellan in a ring with Nigel Benn but maybe they’re just labels on a whiskey pint, they’re on the shelf next to each other like “Hey, we made it,” and maybe they have. Shelf life for life.

2. Sam’s Chicago doesn’t require much “game” or at least if you’re pretty for a white boy it kind of seems like the junkies are all thinking like a bunch of teenage girls.

3. I felt the distinct possibility of having teenage girls want to/pretend to want to fuck me to be alluring but not in a sexual way. All those big eyes with mascara and vodka and older brothers smaller than me. Everything would ride on those brothers being smaller than me, though. They’ve got retractable batons. My little brother once had a friend named Erin that I wanted to like me because she was going to art school in France according to my mom.

4. I worked in a warehouse once. So did I. The people in Sam’s warehouse seem like chillers. I want to throw a jammer with these chillers, and then they do. Same thing about the feeling in “Nice Job”. I would have never said “Nice Job” to anyone driving a forklift. Thought about it though.

5. Limited death types/options on pursuing boxing as a future.

6. Every story has a choice. Listing choices is easy. Spending the night outside of your girlfriend’s apartment because you have no other choice, even if you think the rats are sweet, is a hard choice to make. The movements of Sam’s characters feel both arbitrary and necessary, but always made by one person alone.

7. No matter what, the homeless will always have more friends than you.

8. G’be k’n me is something I’d like to incorporate into my regular speech.

9. If my grandfather always said, “Hey, now who’s this little shithead?” I would be okay with it because my grandfather has Alzheimers. Mine are all dead.

10. Just went to the movies last night. Didn’t question why no one talked to me. Kind of want to move to Chicago. READ MORE >

March 28th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

25 Points: Dear Jenny, We Are All Find

Dear Jenny, We Are All Find

Dear Jenny, We Are All Find

by Jenny Zhang

Octopus Books, 2012

116 pages / $12.00 buy from Octopus Books or SPD

1. MOTHERLANDS

“keats was married to vladimir nabakov

they gave birth to my aunt who spoke no Spanish

and colonized all of western Europe

and that’s why michael’s dad ate my left toe leaving me

crippppled”

(“Lifestyle: I Think I Had a Nice Life and Then I Was Doing Weird Things Like Talking About Having a Bad Life”)

2. I started following Jenny Zhang on her blog Fashion For Writers, back in 2007 or something when I made my living selling vintage clothing to places like France for too much shipping and attempting be less insular by people taking photos of what they were wearing in other places. She was in Iowa wearing coats that made me feel like I could survive winter in Ohio and Montreal, where I was planning to move next.

3. Broke and preoccupied with trying to survive winter by books and digging my car out with hot water to get to the thrift store the morning of 50cent tag day, my Canadian neighbor didn’t own a shovel. “Why doesn’t your city know how to buy salt for their streets?!” I stayed mute and poured water and felt mute that winter, representing a city I had exclusively lived in and identified with and clutched at matryoshka dolls from antique malls lining my shelves and wanting to chuck one at my car for living somewhere that made it requisite.

4. I think I owned, like, 10 vintage coats at one point. I got pretty disgusted with myself that winter.

5. A couple weeks back, Heather Christle reposted the caddis fly larvae works of Hubert DuPrat in Cabinet Magazine and posited the idea that poems are analogous to sheaths, constructed from details of our shifting environments. I didn’t set out to write a companion essay review, but 25 bullet points are hard to extract from concepts this immaculately presented as external, when poetry is thought of as a “internal” and “emotional” when it communicates a lot like clothing. Here’s the traditional review reaction I had if I felt differently:

6. “Dear Jenny makes me feel so many more creepyvoyeurfangirl things, like ‘yikes oh yikes I’m exceedingly aware of how we’re reading ancestrally and seeing the sheaths in their past and future relevant form reading anything, into love poems to things and people and continents dead for centuries!!!!!’” Genuinely felt, but I sound twelve.

7. “Family members are resurrected for a second and then blown back to poppy fields before you can say ‘twat.’ Zhang’s incurably dynastic and reads prosaically in its turns and forms, and they’re bratty and fleshly corporeal in each syntactical bowel movement.” Blurb suited for an

Amazon review: discarding.

8. “We are all find she says

bonjour well because

well she is Chinese and anyway

we don’t use R’s”

(“My Mother Leaves Me a Message Where She Pronounces All Romance Languages in a Deep Voice”)

The semiotic problem of “Asian-American” is the book’s seppuku, which I mean gesturing with misappropriation like Zhang does in so many poems. The inherent difficulty of language in relation to identity as American is as blatant as asking “what are you?” to your face, language can answer that anything but in part. If the audiences of the speaker’s voice heard I was from Ohio, they’d think definitely lived near cows and should have a twangy Gummo accent. How many times did I cringe at Harmony Korine’s decision to film in Nashville? Each and every time I moved.

9. It would be better to use a dung beetle analogy instead of the silk casings Octopus Books gives to its larvae. Dear Jenny’s concerns and permutations of scatology is made legitimately profound, or find its profundity is pointed at without making the profane pornographic. Example:

10. “. . .I’ve been coursing through the finite rivers

the smudge of black on yr fingertips and I’m yrs

ya cunt, I’m yrs, yr the cuntiest

cunt I’ve ever cunted” (“Key Phrase”) READ MORE >

March 26th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

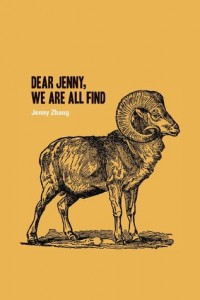

25 Points: Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (on a postcard)

Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (on a postcard)

Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (on a postcard)

by Michael Kimball

Mud Luscious Press, 2013

162 pages / $15.00 buy from SPD or Amazon

March 21st, 2013 / 12:09 pm

25 Points: The Man Who Noticed Everything [UPDATED]

The Man Who Noticed Everything

The Man Who Noticed Everything

by Adrian Van Young

Black Lawrence Press, 2013

200 pages / $16.00 buy from Black Lawrence Press

[Update]”The Sub-Leaser,” discussed here, is now available to read in Electric Literature’s “Recommended Reading” [End Update]

1. I first met Adrian Van Young at 2012 AWP, when he was hanging out at the Gigantic table. I remembered him as an engaging person to talk to. That’s saying a lot, cuz, you know, AWP.

2. Six months later he emailed me about reading in Baltimore. That’s when I remembered what a nice guy he was.

3. His email was cordial but also professional, and he attached a press release about his book, The Man Who Noticed Everything, and a headshot. The color scheme in the photo matched the colors on his book jacket: black and dark green.

4. Ben Marcus said “you’d think this book was an anthology collecting the work of the best young writers of the new generation”—talking about The Man Who Noticed Everything.

5. So we set up a reading for January, even though I hadn’t read his book and even though the main provision for the series that Stephanie Barber and I run is that we’ll only host writers whose work we really admire. I guess the thinking was, this guy has his act together.

6. And he does. I’m not just saying that because he brought a fresh bottle of Jameson to the reading.

7. At the reading, Adrian read a short story. Sometimes I have a hard time listening to fiction. It can be so boring.

8. But while Adrian read, I laughed and laughed. The story was called “The Sub-Leaser,” and listening to it, I felt like it was full of jokes. Or, actually, it struck me as a better kind of funny writing, in which there aren’t actually jokes, but the whole concept (and the way the concept is delivered) is meant to be funny.

9. What’s more, the funniness happens within the prose, which is primarily descriptive, and that is a really hard and precarious thing to do. The story’s narrator is describing his apartment. He says, “My apartment is a standard one for the part of the city where I live. It begins at the door, which opens, like so, to show the splintered wooden hallway that I mentioned before. On the right is a bathroom, ill-sequenced of tile, with a sink built onto the wall and a bathtub, where a thin and mildewed curtain hangs, clad in a pattern of green and white plaid. To the left of the curtain, an insolent toilet, coated with a film of brown.”

10. “ill-sequenced of tile”? “an insolent toilet”? You see what I mean. The whole story is like that. READ MORE >

March 19th, 2013 / 11:09 am

25 Points: The Sounding Machine

The Sounding Machine

The Sounding Machine

by Patty Paine

Accents Publishing, 2012

71 pages / $12.00 buy from Accents Publishing

1. “Still” is a poem about a girl, in her stepfather’s bedroom, holding the “unspooled” film of frames showing “Linda Lovelace’s bottomless / throat” against “curtained light.”

2. The girl’s ears are “cocked / for gravel beneath tires.”

3. She is afraid that her stepfather will return, angry.

4. “Still” is a poem about abuse, and how the memory of that abuse is wrapped and “swallowed” like the “first flash of desire”; that “chasm / of silence, her mouth.”

5. “Still” is not the first poem of The Sounding Machine, but the one I returned to the most. Paine’s collection accumulates, but “Still” is the best pivot.

6. The Sounding Machine hurts.

7. This is a book about grief, focused on the loss of a mother. So Nyo Kim. A woman who married an American soldier during the Korean War. The narrator of many poems in this collection–apparently So Nyo’s daughter–is nearly peeling with this grief.

8. “Sometimes I stop looking/ in mirrors.” “Sometimes I feel / like a child with holes / in my pockets, every day losing / some small stone of myself.”

9. The Sounding Machine made me feel, but Paine was also able to control me, to wire me shut with words. “Ars Poetica” warns that “there are days / when language is heavy furniture you push around / a house made of nothing / but hallways.” The narrator admits “sometimes a poem can lie.”

10. But I want to believe her lies. READ MORE >

March 12th, 2013 / 1:30 pm

25 Points: May We Shed These Human Bodies

May We Shed These Human Bodies

May We Shed These Human Bodies

by Amber Sparks

Curbside Splendor, 2012

156 pages / $12.00 buy from Curbside Splendor or Amazon

1. Most of the stories in Amber Sparks’ collection, May We Shed These Human Bodies, contain elements of fantasy. This surprised me, because the only other story of hers that I’ve read was straight-up realistic fiction. In fact, pretty much everything I read is straight-up realistic fiction. In the case of Amber Sparks, I humbly make an exception.

2. Sparks does a good job of mixing fantasy and realistic details in the same stories, so they seem to take place in some dream-like space where everything is fucked up and beautiful.

3. One story has a hero who goes on a quest with wizards and swordplay, but during his downtime he smokes cigarettes and daydreams about sports cars. In another story, Peter Pan’s Lost Boys play videogames. And there’s a story about a grim reaper character who wears button-down shirts and chinos.

4. In the Death story, I like how he’s made to seem like an old guy who’s tired of his job, just some loser shuffling around in his bathrobe. And I like how all the humans are unimpressed with him, or by being dead. They call him “The Hall Monitor.” They think the afterlife is “lame.” They are irritated because there are no books.

5. A blurb on the back of the book calls these stories “fables,” but they are not actually talking-animal stories with easily identifiable morals. More often, they are portraits of people in great pain.

6. There is a story about a girl whose boyfriend dies. The story includes these sentences: “… pain is not you, but it is yours, and you cannot return it ever. … it will be with you like an old war wound or scarred-over burn, even when you’ve forgotten what it means or where it came from or who drilled it into your skin, when the first nerve ache began.”

7. There’s a story about Paul Bunyan, and how he’s so big that he accidentally kills people. And he’s gotten old and has arthritis in his wrists and a cramping back. And Babe the Blue Ox has died, so Paul Bunyan is lonely, and he’s been a lumberjack all his life but at last knows the time has come to retire.

8. An aging Third World dictator stays up late at night drinking whiskey and watching Westerns on DVD. Americans sometimes come to visit, but they won’t drink whiskey with him. “The dictator understands that American men no longer have any balls, like when they used to herd cattle and hang men from trees. Now they drink like little girls, with tiny sips, nervousness written all over their milky faces.”

9. Robert Gorham Davis wrote that a story must ask–and answer–a single question: “What is it like to be that kind of person going through that kind of experience?” I think every story in Spark’s collection fits this bill. Every one except “All the Imaginary People are Better at Life.” That one’s just crazy.

10. Just kidding. It’s actually a really cool story. It’s about a girl who cracks up and destroys her relationship with her boyfriend. She speaks to imaginary friends via “space wires.” She tells her imaginary friends her fantasies about running away to Maine and living off of lobsters, but her imaginary friends think she’s crazy. Her imaginary friends are sensible. They offer practical advice. READ MORE >

March 5th, 2013 / 4:45 pm

25 Points: Percussion Grenade

Percussion Grenade

Percussion Grenade

by Joyelle McSweeney

Fence Books, 2012

96 pages / $15.95 buy from Fence

1. “Hold a cheerleader’s cadaver up to Nature.”

Percussion Grenade is full of these lines that leave me a little breathless, a little confused, satisfied, sad, all sorts of things. I think the dead cheerleader is an accusation: evidence against the concept of nature.

2. “I maketh you lie down in fracked pastures

in central Pennsylvania

o my blood boils, my tapwater burns”

My favorite part of this book is The Contagious Knives: A Necropastoral Farce which made me put down the book and step away, walk around the block a few times, and then finish the book.

3. Since Kyle Minor wrote on this book here I’m going to try to focus on the The Contagious Knives and a few other sections of the book that he didn’t focus on.

4. I think some concepts that Tim Morton uses in his books Ecology Without Nature and The Ecological Thought are useful for thinking about the necropastoral. The essays Dark Ecology of the Elegy and Queer Ecology are also interesting to read along side Percussion Grenade. The authors are not strangers, and other people have talked about them together.

5. Object Oriented Ontology and Speculative Realism might also make an interesting groundwork for looking at Percussion Grenade, the rest of McSweeney’s work, and the Necropastoral, but I’m not sure what to say about it at this point.

6. “The ecological thought includes negativity and irony, ugliness and horror.“ This quote from Tim Morton seems like it applies to the Necropastoral of Percussion Grenade.

7. “To appear to be acting masculine, you aren’t masculine. Masculine is Natural. Natural is masculine. Rugged, bleak, masculine Nature defines itself through contrasts: outdoorsy and extraverted, heterosexual, able-bodied—disability is nowhere to be seen; physical wholeness and coordination are valued over spontaneity.” From Queer Ecology

8. McSweeney has a particular interest in the marginalized, the other, all of the opposites of able-bodied, heterosexual, extraverted. She’s interested in how a particular kind of power or ability is derived from instability. The Contagious Knives is full of allusions to Tiresias, the archetypal seer, who happens to be transgender and blind.

9. “My Prius drives to the reservoir for some system downtime

without me: to blow off steam. There runoff collects

from picturesque slopes and shops. O Jeunesse, Dream

Prius, Brainless, Brained.”

Mont Blanc (lines 1-4) – Joyelle McSweeney

“The everlasting universe of things

Flows through the mind, and rolls its rapid waves,

Now dark—now glittering—now reflecting gloom—

Now lending splendour, where from secret springs

The source of human thought its tribute brings

Of waters…”

Mont Blanc (lines 1-6) – Percy Bysshe Shelley

10. The Prius replaces the mountain and Ravine of Arve as object of aesthetic and philosophical contemplation. The Prius becomes a sort of liaison to the non-human, communing with the runoff. READ MORE >

February 28th, 2013 / 12:03 pm

25 Points: Fjords Vol. 1

Fjords Vol. 1

Fjords Vol. 1

by Zachary Schomburg

Black Ocean, 2012

72 pages / $14.95 buy from Black Ocean

1. Fjords Vol. 1 is something I could have read in a few hours—easy.

2. It took me 17 days to read Fjords Vol. 1 all the way thru.

3. Fjords Vol. 1 is 57 pages.

4. I have been fascinated/infatuated by Zachary Schomburg-stuff for quite some time. I sent him an email once but he never replied. I assume this is because he was too busy writing awesome fucking poetry.

5. If I wrote awesome fucking poetry like Zachary Schomburg, I probably wouldn’t have the time to reply to emails from people I have never met IRL.

6. It’s not very hard to read Fjords Vol. 1, which is nice. But it’s also not meant to be very hard, I don’t think. It’s like something that is easy to learn but hard to master. Like chess, for example. Or swimming. The Tecktonik dance. I don’t know. (But) that’s how I feel about Zachary Schomburg poetry.

7. If Fjords Vol. 1 had been a homework assignment in high school, I would have found it to be very easy. You could definitely read it all in one night/sitting (if you really wanted to, and I sort of allude to this already).

8. But there is so much to understand and feel and grasp and learn and write down and think about—which is why I love Fjords Vol. 1 so much.

9. Like the poem Staring Problem, in its entirety. “A woman walks into a room. I am in a different room. What has happened to your eyes? she asks.”

10. I feel like, maybe, sometimes, Zachary Schomburg is too smart for me to understand—but I generally feel like this about all poetry—so I keep reading the same line over and over, because I keep thinking “No, this is not hard. I am making it hard. I am pretty sure I can understand anything,” and even after several re-readings (now)—I still cannot grasp everything there is to grasp in the book. That’s fine though. And this is not a bad cannot-grasp-everything. This is a good cannot-grasp-everything. A book that is challenging (to/for) me. Something I can come back to, later in life, after I have read more books and feel like I can finally maybe understand things better. READ MORE >

February 26th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

25 Points: The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral

The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral

The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral

edited by Joshua Corey and G.C. Waldrep

Ahsahta Press, 2012

576 pages / $28.00 buy from Ahsahta Press or SPD

1. The Arcadia Project is not in the least a conclusive project, but rather quite inconclusive. As stated in the Introduction: “an anthology such as this one must be a living and motile assemblage.”

2. Editors Joshua Corey and G.C. Waldrep do not contribute any of their own poetic work. This cuts both ways, as while it shows a measure of humility on the parts of any editor not to grandstand it is also nearly always worth having an editor’s own work (if existent) on hand for clarity of comparison’s sake within the presentation of any selection. How a poet writes interestingly reflects on how a poet reads.

3. Corey pens the Introduction, attesting: “certain tendencies are discernible in the work presented here, all of it first published after 1995” and that “Postmodern pastoral offers a means of mapping the shifting terrain of that world while maintaining its ethical consciousness that the map must never be mistaken for the territory.”

4. Waldrep doesn’t add one word of his own to the book itself. But elsewhere: http://arcadiaproject.net/the-woods-the-technology/ He offers up that it was questions such as:

Which factored into how the anthology came to be, and he adds:

Between 2008 and 2011 Josh and I sifted through hundreds of books—published since 1995 by North American writers, generously defined—as well as hundreds of submissions that came in over our electronic transom, looking for work that would guide us into the forest and try to show us something: work that would leave us alone together (in or in spite of our discrete alonenesses); work that challenged us and terrified us and moved us, that spoke to or around or from within our ecological predicament as 21st-century human creatures.

The resulting anthology is not meant to be definitive, rather provocative and generative, an early draft version of an ongoing conversation between a wide array of poets and the world we live in.

5. The lack of having any such editorial presentation of the framework behind the book’s conception within the book itself feels a disservice to readers.

6. As presented, there’s little tying together of these texts. They are left as isolated cries in a wilderness of language.

7. Poems are divided into four sections: “New Transcendentalisms,” “Textual Ecologies,” “Local Powers,” and “Necro/Pastoral” without any explicit rendering of what may or may not be meant by any of these broadly inclusive and quite permeable categorizations.

8. Questions linger, such as why not include some prose? Both statements of any kind from contributors and/or fiction, non-fiction, or works of theoretical positioning.

9. There’s a band but no bandwagon. Dozens of wheels but no cart.

10. As a reader I yearn to relate these texts in some way. To locate some vein or—what one feels is heard as a bad word by many poets these days—tradition within which the work does participate and indeed does seek continue. Of course doing so may prove some “Romantic inheritances” unavoidable. READ MORE >

February 20th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

25 Points: The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Burton Pike

Dalkey Archive Press, 2008

235 pages / $13.95 buy from Dalkey

1. “So this is where people come in order to live, I would rather thought: to die.” Young Malte Laurids Brigge is talking about Paris. “I have been out. I have seen: hospitals. I saw a man who tottered and collapsed. People gathered around him, that spared me the rest.”

2. Published in 1910, this is Rainer Maria Rilke’s only novel. He is considered one of the most significant poets of the twentieth century and is perhaps best known for Sonnets to Orpheus and the Duino Elegies. I was introduced to him in an undergraduate poetry workshop, taught by Peter Gizzi. He wore a beret and smoked cigarettes in class. He told me: “Read Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet,” and so I did.

3. This is Burton Pike’s translation, issued by Dalkey Archive in 2008. It has been referred to as an “edgy” translation, a “refreshing” one that attempts to preserve the “strangeness” of the original German. Pike says: “Rilke’s prose in this novel is arresting, haunting, and beautiful, but it is not smooth…. It would be a mistake to translate his German into a smoothed-over literary English. That would be to overemphasize the existential element of Malte’s tribulations, and to obscure the radically experimental and daring nature of Rilke’s prose.”

4. The existential elements of this novel are hard to avoid, whether or not you consider this translation smooth. The preoccupations of Malte, destitute poet arriving in Paris to write, concern death and being and becoming. “The main thing was that one was alive. That was the main thing.”

5. In the city, Malte is becoming. He is “learning to see.” He says: “I don’t know why, everything penetrates me more deeply, and doesn’t stop at the place where it always used to end. There is a place in me I knew nothing about. Everything goes there now. I don’t know what goes on there.”

6. The novel is in two parts: Book One and Book Two. There are fragments and sketches and the idea of “notebooks” is apt. There are ghost stories and inanimate objects that are imbued with energy and life. Scenes from Malte’s childhood bump up against fabrications and medieval legends. It is a book that wanders and circles back on itself. It speaks of death and history and imagination. It concerns itself with fear and fever and art.

7. For the sake of poetry, Malte tells us: “One must be able to think back to paths in unknown regions, to unexpected meetings and to partings one long saw coming; to childhood days that are still not understood…. to childhood illnesses that set in so strangely with so many profound and heavy transformations, to days in quiet, muted rooms and to mornings by the sea, the sea altogether, to nights travelling that rushed up and away and flew with all the stars; and if one can think of all that, it is still not enough. One must have memories of many nights of love, none of which resembled another, of screams in the delivery room and of easy, pale, sleeping women delivered, who are closing themselves. But one must also have been with the dying, have sat by the dead in the room with the open window and the spasmodic noises.”

8. All this is necessary for poetry and Malte is in Paris to write. He is twenty-eight and “just about nothing has happened.” And so “it is still not enough to have memories,” he tells us. “One must be able to forget them, if they are many, and to have the great patience to wait for them to come again. For it is not the memories themselves. Only when they become blood in us, glance and gesture, nameless and no longer to be distinguished from ourselves, only then can it happen that in a rare hour the first word of a line arises in their midst and strides out of them.”

9. And so we are led through these scenes of memory and of historical texts and visions and legends that perhaps have become blood in him. Or are in the process of becoming.

10. In one of a series of questions Malte poses to himself and to his reader, he asks “It is possible that the whole history of the world has been misunderstood? Is it possible that the past is false because one has always spoken of its masses, as if one was telling about a coming together of many people, instead of telling about the one person they were standing around, because he was alien and died?” “Yes, it is possible.” He asks these existential, unanswerable questions, responding to each: “Yes, it is possible.” If it is possible that there are no certainties at all, no universally accepted philosophies of living and dying, then it is incumbent upon him, though “young, irrelevant” to write “day and night, he will just have to write, and that will be that.” This is the young poet’s charge. READ MORE >

February 14th, 2013 / 1:02 pm