THE ACT OF MEMORY, “LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD” & THE THING OF INTENTION

SUBJECTIVITY OF MEMORY

Suzanne Corkin’s book Permanent Present Tense: The Man with No Memory, and What He Taught the World chronicles the fascinating case of Henry Molaison. Upon receiving a catastrophic lobotomy at the age of 27, Molaison continued his life as an individual incapable of forming new memories. For the remaining 55 years of his life, Molaison was closely studied by Corkin: his unique tragic circumstances constituted him as a one of a kind empirical specimen of anterograde amnesia, the medical term for his inability of forming new memories. Corkin found in him the ideal means to gain a deeper scientific understanding in the field of neuroscience[1].

Unlike the Drew Barrymore character in 50 First Dates, Molaison spent his amnesic reality in the company of a meticulous observer and not the romantic goofiness of Adam Sandler. The focus of Corkin’s book is the scientific exploration of how new memories are cerebrally processed. Corkin observed the short-span consciousness of Molaison’s new memories along with the variation of the feelings and thoughts he exhibited, as everyday provided a new opportunity to reassess her specimen all over, evaluate and reevaluate the pertinent data. Despite the repetitive occurrence of the same questions within his short-span of memory, Molaison’s responses were sometimes indicative of the formation of new memories. This analysis served as a catalyst for a new neuroscientific theory: contrary to previous popular belief that memories “were indelible snapshots of sense experience, stored in chronological sequence like the frames of a celluloid film,” memories are actually located in more than one location in our brains.

Mike Jay’s exceptional review of Corkin’s book[2], aptly entitled “Argument with Myself,” starts with a powerful definition of memory. Jay concedes that memory shapes one’s identity, but he argues that in addition it simultaneously functions as the (mis)apprehension of a well-founded, whole self: “memory is not a thing but an act that alters and rearranges even as it retrieves.” In this framework, it is evident that the way we conceive our individual realities, as they are constructed by all the memories we hold, are suspect. The manner in which all of us accentuate the details of what happens, both to us and in the world surrounding us is marked by subjectivity. While the degrees of each person’s paranoia and tendency for narrative exaggeration vary, there is no doubt that in most “realities” much is not real.

In an endeavor to make her students grasp this very fact, Mary Karr once began teaching a creative writing course by performing getting in a huge spat with the educational institution’s program director[3]. Once the program director exited, Karr revealed to her students the argument they had witnessed was a simulation. She then asked them to write down their observations and perception of the incident. The students had an arduous time reaching consensus on a collectively agreed objective account of what had just happened in their classroom. This exercise swiftly presents the validity of the very ambivalent nature of objective memories.

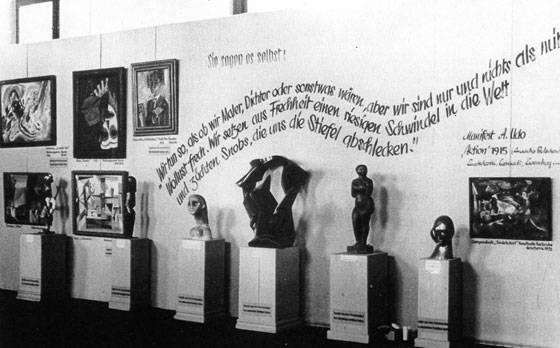

EMBRACING POWERLESSNESS IN DEFINING ART : THE LEGACY OF ENTARTETE KUNST (1937)

The Stayin Alive of the Gallery Show-An IRL Victory

The insightful and highly regarded art-critic Jerry Saltz recently wrote an ambiguously polemical essay in which he crywolfed the death of gallery shows1. The primary theme of his argument is linked to the Internet’s takeover of the sales departments and the URL-manner in which the contemporary art world functions now, eliminating the necessity for the IRL-dimensions of the process.

Discussions that pertain to the broader implications of the Internet in an industry rarely reach an objective conclusion. The art industry undoubtedly constructs a particularly challenging case due to its multilayered and convoluted business model. The argumentation may be shifted in any direction to build a persuasive case for any involved party. Artists gain significantly by creating a powerful web presence: they increase their chances of being discovered and attaining the attention of individuals who may shape their future. Additionally, a much larger audience has accessibility to viewing and becoming familiarized to the work of countless artists through a net simulacrum. Whether they simultaneously “lose” by offering their presence is ultimately subject to their ideology.

In a brusque manner, Saltz asserts that the only criterion in evaluating gallery shows are the sales they garner, or fail to garner. The critic briefly articulates–but neglects to delve into the magnitude of–how this shift relates to his identity as a critic. It would be naive to ignore how the “democratization of the critic2” affects him personally: his role becomes less important offline, as the presence of less people at galleries has an impact on the pragmatic utilization of his hard-earned credentials and expertise.

When accounting for this detail, an evident controversy in Saltz’s essay arises: initially he brings attention to the lack of a meaningful dialectic occurring in physical gallery space, while he later hesitantly adheres to the democratization of criticism by adding that “art is not inherently democratic.” What critic wants to experience others’ seeking of his expertise and input decrease? Saltz does a better job at identifying “the problem” by stating that the “the art world has become more of a virtual reality than an actual one.” Whether it ever was an actual one, or if it solely seemed so to the critic remains debatable.

“The Death of the Gallery Show” introduces a compelling argument. It is interesting to place it in the framework Thomas Frank recently utilized to investigate the authenticity of political statements of David Leonhardt on the topic of economic austerity. Frank’s methodology falls in line with the familiar traditional debate approach: “The point wasn’tfor an individual debater to believe any particular argument and win the room over with the radiance of his faith; it was for him to be able to argue anything.3”

While Saltz argues the end is near, I am not convinced he deems it possible. In a fascinating way, his performativity of argumentation is representative of the very reason galleries constitute alienating spaces for most people: much of the art presented today cannot be a catalyst for discourse. The curatorial content is no longer created for the audience, but is expected to be created by it. Certainly, this has been argued before, but the status quo of modern art has never before been as deeply interconnected with the mass entertainment industry.

The difference between Jeff Koons’ notorious sculpture of Michael Jackson with his beloved pet Bubbles and Tilda Swinton’s celebrated naps at the MoMA is a drastic paradigm of the shift that occurred within this time in the collective consciousness of reality4. Even if we are so alone in our virtual worlds that we need to be made aware of it via art, this never becomes sufficiently clear in such grotesquely self-aggrandizing projects. This intentionality in mirroring whatever the audience wants to see can be powerful, but it cannot escape being contrived. Ultimately, it appears as if the art world viewed drawing more elements from the entertainment industry as a means to attract more people and yield better sales. The performed bravado and intentional ambiguity of such contemporary art projects make people show up in gallery spaces less frequently. Why turn to culture when the culture is the entertainment?