Mission Creek 2014 and all its Art, Film, Music and Lit is almost upon us with Phillip Glass, Rachel Kushner, The Head and the Heart, Warpaint, Brian Evenson, etc.

***

And this year HTMLGIANT will be part of the Litcrawl (Friday, April 4th) where Colin Winnette and Grant Maierhofer will read from their work featured on HTMLGIANT as part of an “Electronic Literature” event at The White Rabbit.

***

(The Iowa Review, Red Hen Press, Hobart, Spork, Black Ocean and others will also be a part of the Lit Crawl.)

***

Go here for full calendar

The Persistence of Crows

The Persistence of Crows

The Persistence of Crows

by Grant Maierhofer

Tiny TOE Press, 2013

173 pages / $12 Buy from The Open End

Coming of age narratives are usually as riddled with tropes as low-budget horror films. Sure, there are a few outstanding novels in the genre like Bret Easton Ellis’ Less Than Zero and Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, but the list of must-reads grows at the speed of stalactites. Grant Maierhofer’s The Persistence of Crows, from Tiny TOE Press, has joined that short list with a story full of depression, too-beautiful moments, and kind of soul crushing realness.

Henry Alfi is a young man who’s recently stopped using drugs and alcohol. Sadly, his new unaltered state of consciousness has him feeling bored, lonely, and profoundly disenchanted by the people and institutions that surround his life in the Midwest: AA, friends, college, family, the women he dates, etc. One of the few things Henry enjoys is writing, so a trip to New York with his college newspaper seems like the perfect opportunity to get away from everything for a while and ponder the future. Surprisingly, the trip turns out to be more than an escape and Henry finds himself ready to move, eager to discover the world, sure that he wants to pursue a career in writing, and falling quickly in love with a woman who shares his view of the world.

The Persistence of Crows starts out as an unimpressive narrative about a young man about to embark on a trip to NYC. Despite the lack of an exciting start, Maierhofer manages to set the hooks in via his use of language and character development. The strategy is risky, but he pulls it off. The prose has a unique, somewhat offbeat rhythm and the dialogue is sharp. Also, he establishes early on that his main character is deeply flawed but also thought-provoking and the kind of individual you want to learn more about:

“It felt better to be walking by myself. I didn’t feel unsafe when I was alone. I didn’t care if some bum crept up to me. I would fight and what would happen would happen. It was when I was with others that I got nervous. It’s far easier for me to imagine defending myself than it is protecting the life of somebody else. Their life can be completely abstract even if they’re standing right next to you.”

Henry is the poster child for the broken/dissatisfied/irritated/Google generation. He feels alienated, gloomy, and deracinated despite being home. His life on drugs and alcohol was bad, but his life without them isn’t better. The story seems to be a character study for a few chapters because the dark past, recent troubles, and disturbed state of mind are all in place, but it changes drastically once Henry lands in New York. A bit of dark humor and pervasive dreariness quickly switch to a beautiful homage to the Big Apple in which Maierhofer’s knack for language and imagery take center stage:

“The rain beat down on all of us. These youthful faces soaked in the same Hudson River breeze as the old folks arm in arm enjoying the bright lights of the city. I was surprised to see that even in the afternoon the lights shone as brightly as all of the photographs I’d seen of the city at night. When I turned the corner, all breath was taken out of me. Any worry I had ever felt in my entire life up until that point turned into a sense of power as I stood there staring at the gray and red and silver world encircling me.”

The homage to NYC saturates the narrative for most of the middle third of the novel, which contains a few odd encounters between Henry and locals that deserve to be in film, and eventually bleeds into the brief but magical time Henry spends with Sara Lee Poe, a fellow journalist he meets at a panel. The duo allows the city to filter everything they experience together and they weave a cocoon of shared ideas and passion that blinds them from their imperfections. As soon as their time together is over, reality comes crashing in and Maierhofer uses it to destroy both everything Henry built and readers’ emotions.

The Persistence of Crows switches between a romance, a bizarre comedy, and something that pulls from most of Woody Allen’s early work. It is an exploration of loneliness, addiction, the construction/obliteration of love (or at least a reasonable facsimile), and disconnection. Maierhofer’s Henry thinks trying to pay attention to what others have to say can only lead to suicide, but he ends up contemplating suicide because of things that were left unsaid. Stories about falling in love in oh-so-magical New York are as old as the city itself, but Maierhofer has updated the premise to offer the honesty and ugliness that fans of authors like Tao Lin, Ana Carrete, and Sam Pink demand, and the result is worth a read.

***

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, journalist, and book reviewer living in Austin, TX. He’s the author of Gutmouth (Eraserhead Press) and a few other things no one will ever read. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Verbicide, The Rumpus, HTMLGiant, The Magazine of Bizarro Fiction, Z Magazine, Out of the Gutter, Word Riot, and a other print and online venues. You can reach him at gabinoiglesias@gmail.com.

January 10th, 2014 / 11:00 am

Some Recently Acquired Reading Materials

Note: This is a small handful of books that I’ve either recently enjoyed or merely received in the mail, a more extensive review is probably in the works for a few of them, but for the moment I wanted simply to list the things themselves with notation where it seemed apt.

***

1. APOLOGY Magazine #2 I actually wrote the magazine’s editor Jesse Pearson about this one because I’d read that in the first issue they featured a Frederick Exley piece and that made me very happy. He was kind enough to send me the second issue and I’m planning to review it in a similar fashion to that tome I wrote about Out of Nothing, as these two things (Apology/OON) are some of the most exciting printed literary journals/magazines/etc. I’ve come across in quite some time. #2 features work from noir master David Goodis, as well as an interesting photo/essay from Richard Kern; and hijinks from Tim Heidecker; work from Steven Moore, Jerry Hsu, Anthony Berryman, and many others. I love the way this magazine feels very much.

2. Gigantic Failures by Mark Anthony Cronin. I bought this collection of short fiction (Disconnected Stories, the cover reads) awhile ago because I’d read a bit of Cronin’s work here and there online and was curious about the effect of one continuous block of his headspace. I was not disappointed. This is probably my favorite collection of short fiction put out by a small press this year, and reading it I was reminded of a younger version of myself voraciously reading through Jesus’ Son or The Big Hunger. I spoke with Cronin once about his appreciation for P.T. Anderson and since then can’t shake the notion that the absurdist-yet-highly-emotive world depicted in these stories connects easily to the fragments of a Magnolia or Boogie Nights. I fucking love this book. Amber Sparks, another author of a fascinating recent collection May We Shed These Human Bodies, had this to say “’The Man’s name was erased, totally forgotten. He became something beyond himself: a sermon given unto the world…’ Make no mistake: Mark Cronin has given us a collection born of myth and archetypes. Despite the modern settings, despite pop culture references sprinkling the stories, despite the piles of Walmarts and McDonald’s and AK-47s—these are stories that get at the heart of very simple, age-old truths, and the dream of what it is to be human in any time.” An excerpt was published at Volume One Brooklyn, and you can order the thing here.

3. Technological Slavery: The collected writings of Theodore J. Kaczynski, a.k.a. “The Unabomber” introduction by Dr. David Skrbina Over the summer I had the immense pleasure of reading Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, and as a result have since kept my eye out for the occasional potentially-fucked narrative pressing the reach of reality that much farther. For awhile I was convinced there was something deeply profound in the connection between the Beach Boys’ Dennis Wilson and Charles Manson, and as a result purchased Wilson’s solo record and spent several weeks researching that element of the Manson ordeal. I came up with very little, but that isn’t really the point. Lately, a research obsession has been Kaczynski, and it’s largely due to my ignorance of the trajectory of his life thus far. When I was younger “Unabomber” was simply something people said when you wore a hoodie up and a pair of sunglasses, but since then I’ve realized that Ted Kaczynski is easily one of the most striking and disconcerting figures America’s ever seen—akin to Howard Hughes, I’d say, or the entire Kennedy family and all intertwined in their narrative rolled up into one man. Entering Harvard at sixteen, he then went on to become UC-Berkeley’s youngest professor before entering the woods to eventually embark on a mail-bombing spree that baffled the country until his “manifesto”—featured in this volume—“Industrial Society and Its Future” was published by the New York Times and a family member noted his writing style and he was locked away. He’s still alive, and recently sent his address in prison to the Harvard Alumni Association along with a list of accomplishments including his prison sentence. All that aside, because the list of Kaczynski’s criminal charges isn’t nearly as fascinating as the rest of his life, I bought this book because it felt like a source of information regarding our world that won’t even be considered for years to come. I think of entire college classes devoted to studying the Nazis in Germany in small Midwestern Universities and the prospect of this happening in 1950 being completely preposterous. I think of years to come when entire disciplines will exist devoted solely to the analysis of the Zapruder footage, say. I applaud Feral House for publishing this and other highly important titles. I am very excited that I as a living human animal am able to read this sort of thing without being arrested or something and that information is out there for us if we desire it, I dunno. I’m an idiot.

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

Hill William

Hill William

by Scott McClanahan

Tyrant Books, Nov 2013

200 pages / $14 Buy from Amazon

There’s a moment in John Fante’s The Road to Los Angeles wherein his protagonist, Arturo Bandini, has taken all the photographs of beautiful Hollywood starlets he ritualistically masturbates to in the closet into the bathtub with him to drown them, so to speak, and attempt to move on with his life. In a matter of three or four pages it distills the awkwardness and hilarity of growing up into a beautiful, imaginative vision of this young man thrashing around in the tub with photographs surrounding him, their faces beginning to run. Around halfway through Scott McClanahan’s newest work, Hill William, I realized that I’d felt the same sense of awkwardness and hilarity for the past 80 pages, only subsiding briefly when one tale reaches its close, and the next begins.

Fans of McClanahan are well aware of his ability to convey these qualities through a multitude of works. Be it his early collections of Stories, The Collected Works from Lazy Fascist, or the recent Crapalachia, I’m hard pressed to think of any writer working today who so seamlessly blends the horrific with the heartfelt, or small town American mania with the universal notion of comedy, and a desperate search for meaning.

Hill William, for me, feels a bit like the perfect blend of his early short fiction with the all-too-real tales of Crapalachia, while transcending anything thus far and reading like Geronimo Rex-Barry Hannah got into a bareknuckle boxing match with Person-Sam Pink. (This was another comparison that immediately came to mind, if you’ll pardon my digressive tendency.)

Hill William is McClanahan’s first novel, and yet it functions more like a novel-in-stories, the protagonist presenting the reader with any number of characters from his youth like Gay Walter, a “sissified” young man with a pet hamster named Hardees, or Derrick Anger, a boy who introduces young Scott to masturbating via a “1970s’s style dirty book that didn’t even have any pictures in it really but just these drawings of people having sex and these little dirty stories to go along with them.” With each chapter heading comes a new interior landscape wherein the narrator confronts some element of growing up, and yet for all the coming-of-age apparent in Hill William there’s just as much obsession with the surrounding community and the idea of taking on new lives and personalities to pass the time.

Early on, in “Rainelle,” the narrator says “I looked out over the continentals on the street below me and in these houses were people walking around in the lights they just turned on. I sat and felt so lonely because I was only one person and couldn’t be each of them.” This, by itself, got me thinking about McClanahan’s status as a sort of modern day Carver or even Faulkner, in his ability to sit down and narrate quick glimpses into such a wide range of lives. Some of that curiosity about this range of lives explored in his former stories seems to come out again in this urge to embody the whole community while telling one character’s life.

Later, Gay Walter begins singing Alabama’s “Roll On,” when the narrator observes “he was no longer Gay Walter but someone else. He sang and we watched and listened and he was no longer on a porch in the mountains, but he was on a stage somewhere. He was no longer lip synching to the radio, but he was our own private superstar. He was singing our song and we were singing along.” Suddenly the middle of nowhere becomes the center of the universe and it’s due to a mixture of McClanahan’s intimate prose and the unobstructed sight of a child. No longer are we as a reader in the mountains of Appalachia but traveling above it all with a gang of strange perverted nobodies desperate to feel comfortable. The microcosm quickly becomes the microcosm, the particular the general.

December 9th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Some Unscientific Thoughts on Depression

Depression is a different animal entirely. For the depressed person, the bulk of precedents—be they figures one admires that also dealt with depression, or works that seem to encapsulate the modern understanding of this phenomenon—have occurred in the last hundred years or so; and although it’s not difficult to develop a strong empathy for depressed figures like Lincoln, Nietzsche, or Albrecht Dürer, the lines of history tend to blur and complicate personal afflictions to such an extent that for every book that might exist exploring the various miserable icons we’ve had, there are hundreds documenting their triumphs and love affairs to bury these desired texts neath the fantastical self help mega library.

Depression is a different animal entirely. For the depressed person, the bulk of precedents—be they figures one admires that also dealt with depression, or works that seem to encapsulate the modern understanding of this phenomenon—have occurred in the last hundred years or so; and although it’s not difficult to develop a strong empathy for depressed figures like Lincoln, Nietzsche, or Albrecht Dürer, the lines of history tend to blur and complicate personal afflictions to such an extent that for every book that might exist exploring the various miserable icons we’ve had, there are hundreds documenting their triumphs and love affairs to bury these desired texts neath the fantastical self help mega library.

TWO FEASIBLE PRECEDENTS

The first, and perhaps most obvious best friend to the depressed person post-1995 who happens to enjoy literature, is probably David Foster Wallace. Before him, the aforesaid lines of history tend to make the case of Sylvia Plath or Van Gogh fairly cut and dry, to the extent that Plath’s life might be seen as her sitting down at a desk and writing some beautiful works, then immediately falling into such a vat of misery that she stuck her head in an oven, the same model largely applies for Van Gogh except it’s paint, with a bit of ear-severing—though not as drastic as history has made it out to be—and the man shooting himself in the heart twice before walking back into the city undead, only to die two days later. With Wallace, however, we have an accomplished intellect who came to suffer severely from depression after the road had begun to be mapped out for him. Already well into his college career—and of course you can argue that his depressive tendency existed before this, but as I understand it this was when Wallace really came to blows with the malady—he seemed destined for literary accomplishment before being thrust into the void of chemical dissonance and thus forced to consider contemporary (this is important) means of salving the indiscernible wound. And, luckily for us, he managed to write some of the most fascinating fiction and non- about the subject to happen in years. This is a curious thing to me. For all the talk I’ve heard of Wallace’s mastery over the contemporary form, or something, I seldom hear discussed his great command over the subject of fucking misery, modern boredom, or complete and total suicidal ideation. I guess it’s hinted at much of the time, but as far as I’m concerned the guy is close to our American Foucault as it relates to the depressive animal, with “Good Old Neon” or the Kate Gompert portions of Infinite Jest—perhaps my favorite in the whole book, weirdly enough—or Wallace’s nonfiction and more—the subject tends to permeate everything as far as I’ve gathered—what we have in Wallace is a guide for the solving of the plight described by Scott Fitzgerald years prior to this, that “the natural state of the sentient adult is a qualified unhappiness.” For more on this I highly recommend Postitbreakup’s fairly recent post for Dennis Cooper’s blog, “David Foster Wallace’s triptych on depression.” READ MORE >

5 Points: POOR ME I HATE ME PUNISH ME COME TO MY FUNERAL—- (by Grant Maierhofer and Kil)

“He saw her standing near the creek, near the road, near the stoplight. A stoplight looks bright red when your eyes haven’t seen sun for months. A stoplight looks like your best friend when the wind hovers low and the night springs up like some old widow slashing wounds throughout your flesh. You wait for some quickness, some instance of recognition, and nothing comes. Nothing.”

***

1) POOR ME I HATE ME PUNISH ME COME TO MY FUNERAL (PMIHMPMCTMF) is a collaboration of poems and images brilliantly paired by Grant Maierhofer and the artist Kil. Hard copies are available through EDEN CHAPBOOKS. Or you can check it all out on-line here.

2) These poems were (and are) a revelation for me. The only comparison that comes to mind is that I experienced something similar when, many years ago, I first encountered the prose poems of Max Jacob and Jean Follain in a 3-poet book titled “Dreaming The Miracle.” Maierhofer’s poems here in PMIHMPMCTMF glow wisely in the way Follian’s do. They also have, like Follain’s best efforts, a kind of sacred Sepia feel. They are, in short, quite wonderful.

3)) I’m all for religious bashing and I’m often guilty of being crude (badly crude) about it. Maierhofer though is extremely effective, wise, restrained and kind of off-handed about it. But, it’s sledgehammer wise and sledgehammer off-handed: “A perfect world if not for churches. If not for those hulking black tombs READ MORE >

October 21st, 2013 / 6:11 pm

Grant Maierhofer’s SUMMER READS

Such Times by Christopher Coe

Such Times by Christopher Coe

I read Coe’s I Look Divine earlier this year after reading about his connection to the Lish workshops and deciding he seemed like my kind of writer. With his first book, I was absolutely correct; it’s a spare portrait of two brothers via one’s memory, and the prose is some of the tightest and most touching I’d read in months. Such Times is Coe’s last book, and its primary concern is the AIDS epidemic and its effect on the lives of three young gay men. It’s a tragedy because Coe himself died of AIDS in the 90s, and I have no idea why this book is so attractive to me at the onset of summer. (…)

#2 of The Quarterly

#2 of The Quarterly

Again, because of Lish, I started buying up old issues of The Quarterly on the internet from time to time and have been making my way through them. There’s no preamble in these, no discussion of authorial intent, just a nice slim edition from Vintage that immediately thrusts you into the most powerful short storytelling voices in the late 80s. I recognize hardly any names in this one, which will probably mean they’ll all meld together even more so than the last, but I don’t care. The stylistic efforts being made between these pages are fucking huge.

The Sluts by Dennis Cooper

The Sluts by Dennis Cooper

This year was sort of fucked in the face by an extremely fast reading of Cooper’s George Miles Cycle—I intended to write something about it and continue to fail immensely—followed by an equally quick reading of the first Grove Press paperback edition of Sade—the major face-fucking then being done by Philosophy in the Bedroom. I’ve been a fan of Cooper’s for quite some time now, and have read most of his books except for this one. I saw a list somewhere of books that sort of warped Ariana Reines’ perspective, and this was on it, so I’m real excited.

June 18th, 2013 / 11:00 am

OUT OF NOTHING #[0]; Or, blurbing the whole cacophony

[out of nothing] #0: theoretical perspectives on the substance preceding [nothing]

[out of nothing] #0: theoretical perspectives on the substance preceding [nothing]

Ed. [out of nothing], October 2012

144 pages / $12 Buy from Amazon or Createspace

When the opportunity presented itself to review the printed edition of [out of nothing] recently, I jumped on it quicker than anything I’ve jumped on since I was ten. The idea in my mind wasn’t even necessarily to “review” OON but just to be able to hold the thing in my hands, first and foremost. [out of nothing] and Lies/Isle are obsessions of mine of late—the online versions, that is; these strange permutations of art and thought and science and everything intellectually captivating you could imagine organized into endless mazes of online content. If we’re to believe in such a thing as collaborative arts on the internet, this, in my opinion, is the sort of thing heading up the effort.

So anyway, I immediately requested a review copy of [out of nothing] and when it reached my house I felt connected to something likely akin to movements in the art scenes of New York in the 70s and 80s or Berkeley and various Western lands in the 60s. Here was the personification of serious writing and art in the twenty-first century and here was my opportunity to consider it. To be sure, considering it is likely the greatest feat I’ll here be able to accomplish. I’ve tried over the past few months to conceive of items to potentially submit to a publication like OON and I can’t for the life of me make it happen. Perhaps it has something to do with the collaborative nature of the thing, perhaps the three editors and founders of OON are just that-fucking-savvy that they’ve managed to push the intellectual envelope even more, I’m not sure. All I know is, if The New Yorker was once taken (dreadfully) seriously as a hub to receive one’s culture, [out of nothing] (both the print and online version) is its strange twenty-first century cousin doing bizarre rituals/experiments in the city’s basement trying to reanimate the corpse of Soren Kierkegaard.

But I digress:

Considering the structure of this anthology, I’m going to move through and evaluate each piece in order with as calculated a response as I can muster. This being an anthology of the highest order, my efforts as critic of OON will be best if the responding structure of my own writing not attempt the strange collective genius inherent to that which I’m writing about. I featured the subtitle “blurbing the whole cacophony” to draw comparisons with Melissa Broder’s piece “blurbing every story in the new New York Tyrant,” because it’s helpful to have something to riff off of this time of year, when the mind slows down and wants only to recoil into hours of sleep. O sleep.

(Furthermore, given the array of materials that exists within the 144 pages of OON, the length and style of my interpretations will vary, and where my words will surely fail to illustrate the images/texts and their substance, I’ll include scanned images of pages because I’m not beyond that and I love this fucking thing too much to assume to understand it.)

Now, regarding the introduction:

IS THAT ALL THERE IS?

by Jon Wagner

Reading this, I’m reminded of something Rick Roderick says in his lecture regarding the works of thinkers like Foucault, or Habermas—and one could easily expand this to Deleuze, or even Derrida if one was so inclined—whose works can hardly be called “philosophy,” in the traditional sense. He goes on to emphasize that contemporary “thinkers,” must encapsulate more of society than was previously expected of philosophy, and that the greats like Foucault or Nietzsche must be acknowledged as something else to be understood. Not only can Wagner’s introduction not be called an “introduction,” in the strict understanding of the word, but it belongs alongside the works of those aforementioned thinkers as something transcending mere criticism, philosophy, history, geneology, ontology; the list goes on. What’s given here is first a consideration of the idea of [nothing],’ and what the bracketing of the word/idea itself might mean, then an introduction to the proceeding texts is given and it’s briefly explained that commentary will be provided by a handful of “Jabberwocks,” along the way—“Benjamin, Baudrillard, Derrida, and Kierkegaard. This is something I’ve not seen done, like, ever, and in addition to creating this extremely fun intertextual environment while reading, it brings to mind all kinds of questions about the apocryphal, marginalia in general, and ghosts. My own thoughts here channel and mimic Deleuze, Pasolini, and Miss Peggy Lee within a restricted economy of expression that bleeds a general excess in the very effort of constriction.” I.E. OON does not seek to be a mere anthology, nor even a mere physical book, and will go so far as to resurrect the dead in texts to bury its collective mind in the concepts of nothingness as deeply as possible. This is unlike anything dubbing itself an anthology that I’ve yet experienced, and onward we must go.

PRE-WAR

Nicholas Grider

I’ve wondered a great deal lately about the idea of a text somehow avoiding the idea of a start and finish entirely, and bridging the gap towards something more diffuse. One thinks of Joyce in this regard and Finnegan’s Wake, or perhaps something more contemporary like Lost Highway, but even still these things do have a beginning as far as location is concerned (the “first” page, the “opening” of the film). I’d feel safe in positing that Grider’s piece comes close to achieving this rather timeless sensation. Although the writing only runs across three pages, the blend here of Walter Benjamin’s and Jean Baudrillard’s insights with the author’s own do lend an eerie, spectral air to the thing and that tied with the fractured indentation of Grider’s lines tempted me to read the thing out of order, forwards and backwards; as many ways as I could considering its brevity. I won’t begin to argue that we’re a great deal closer to printed texts that could actually be called diffuse in this regard, but this first in the anthology does seem to chip away at this idea. I’ll include here the interplay between Grider and Baudrillard, without question my favorite moment in the piece.

“or you have better things to do, you are a background character who laughs a little too long at the funeral parlor with 2.5 walls, you can do a lot of things with flashcuts these days, jackknifing, binge drinking, shoplifting, heavy breathing. {}

{Indeed, you can, when the reified even it so much so that a single marker can indicate an

entire conceptual package: an action, a life, an historical trajectory. JB}”

READ MORE >

May 8th, 2013 / 11:00 am

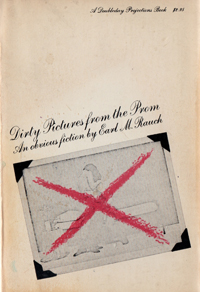

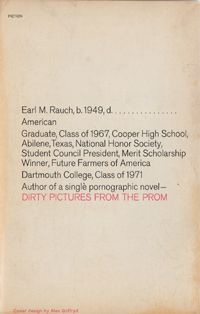

Needing Earl M. Rauch

I discovered Earl M. Rauch’s Dirty Pictures from the Prom on a miserable snowy day this January (2013). As is occasionally the case, I decided to spend said miserable snowy day inside as much as possible—it was a Friday, and after finishing up the day’s classes I wandered over to an antique store in Eau Claire, Wisconsin; a place not known exclusively for its cultural presence (Bon Iver lives here, I guess, some fantastic sauce is made here at Silver Springs, and before dying in a plane crash several days later Ritchie Valens, Buddy Holly, and J.P ‘The Big Bopper’ Richardson played here at a building that’s now defunct). This antique store is massive, and awhile ago I used to come here and collect old issues of Esquire with pieces by Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and the like, as well as old paperbacks I’d never heard of. This particular day I already held two Iris Murdoch hardcovers before looking at a shelf on my way out and seeing a spine that read in a florid cursive ‘Dirty Pictures from the Prom Earl M. Rauch Doubleday’ and already having a copy of Under the Net at home I still had yet to read, I dropped the Murdoch books immediately and picked up this strange text.

While in the store I looked up Earl M. Rauch and discovered the book for sale online for prices seldom lower than 100 USD; this made me want to buy it. He was also a largely unknown person who apparently wrote this—his magnum opus, though not his only contribution to mankind’s literary heritage (more on that momentarily)–when he was only nineteen years old; that, plus the heft of this obviously well-conceived novel, made me want to buy it even more. Then further reading in various biographical pieces about Rauch and his prodigious fascination with writers like Pynchon, made me decide that this was the only book I’d ever truly need and that I’d spend the weekend doing nothing but reading it from cover to cover. And so I did.

Some notes on the technique:

1. This book is largely comprised of a straightforward, picaresque narrative about a character named (Osgood) Barnaby Saltzer. Chapters begin and end and as a result you’ve moved on several moments/months/years in his life and been entertained along the way. However, Barnaby had a younger brother named Creynaldo–a prodigious genius, having died when he was only seven and already written many cherished works–and the book features a great deal of his poetry/drawings as well. Furthermore, at the end of many chapters–and before a few, later on–there are notes from conversations between this story’s author Barnaby Saltzer, and his editor; hence the occasional portions where large X’s are printed through entire pages that the editor deemed unworthy–a practice of ‘bracketing’ in the deconstructionist tradition that only serves to make you read harder.

2. Though obviously influenced by the Pynchon novels available at the time (1969) in his extremely funny descriptions of a dangerous and fast-paced America, I daresay Rauch achieved something entirely novel with this work. This is apparent on the cover, ‘An Obvious Fiction,’ calls to mind the typing of Exley’s A Fan’s Notes as ‘A Fictional Memoir’. Rauch seemed to know at an extremely young age that he’d achieved something unprecedented in this regard. Of course variations on this theme of the broken and commented-upon narrative existed, but not quite like this and very seldom in a package as successful as Dirty Pictures.

An Interview With Donald Ray Pollock

Several years ago I was about to board a plane to Virginia where I was to explore the campus of a school that would teach me to become a mortician. It’s since become a joke in various places that ‘I’m here, because my job as a mortician fell through…’ etc. Before boarding the plane, I grabbed a magazine—my memory eludes me as to which magazine it was, some cultural blah blah blah; something where books are mentioned—and during the two or so hour ride I read most of the magazine, finally rereading one portion over and over again.

Several years ago I was about to board a plane to Virginia where I was to explore the campus of a school that would teach me to become a mortician. It’s since become a joke in various places that ‘I’m here, because my job as a mortician fell through…’ etc. Before boarding the plane, I grabbed a magazine—my memory eludes me as to which magazine it was, some cultural blah blah blah; something where books are mentioned—and during the two or so hour ride I read most of the magazine, finally rereading one portion over and over again.

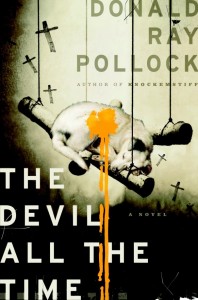

It was a blurb written about a novel called The Devil All the Time, with corresponding cover art featuring mangled marker-drawn crosses and skulls; and a glowing review from somebody somewhere. The writer’s name was Donald Ray Pollock, a name most people recognize along with the titles of his books nowadays.

Again, didn’t wind up becoming a mortician, but on that trip I stopped at a bookstore and picked up a copy of Pollock’s second book, reading it from cover-to-cover on the plane and car ride back to the middle of nowhere in Wisconsin; and for the first time in a long while I started to find romantic little moments along the barren roads beside our car, having Pollock’s eyes to see that you didn’t need New York to have literature, I guess, that sort of thing.

A month or so later I was cursing myself, finding out that Pollock’s first book, Knockemstiff, was sort of a prerequisite for the second—set as they both are in similar vistas of rural Ohio, where everything reeks of old death and strange blood. I picked up a paperback copy of his first as soon as I could and immediately set to reading it.

Both times, in similar and yet subtly different ways, I was floored. Knockemstiff reads as if Raymond Carver and Dennis Cooper had a kid and he lived down the street from Scott McClanahan; gloriously fucked-up images balanced against the monotony and odd sense of peace you get when you’re so far off the radar that you forget it even exists. This is Pollock’s coming out into the world of literature, and he does so with no shit-covered stone unturned. With his second, The Devil All the Time, it could be said that Pollock prolonged the sting of his previous short stories and the result is a portrait of American life nearly impossible to forget. The book opens with a father and son walking out to a small grove where they’ve been sacrificing animals, hoping for some kind of good fortune, and from then on it barrels headlong into a story spanning many years and veering off into these dirty cinematic takes on growing up, dealing with death, and out-and-out crime.