ON CARDBOARD: Michael Kimball

Michael Kimball still feels like a bit of a sleeper hit. It’s not as if people aren’t reading him, or discussing him, or heeding his presence in general on earth; but when you yourself pick him up and feel the various array of facial slaps he harbors in his repertoire, you can’t help but think his work’s been waiting around for you to discover and devour it.

@MichaelKimball

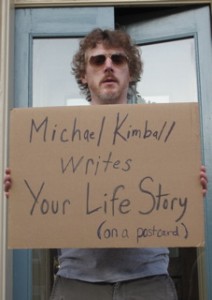

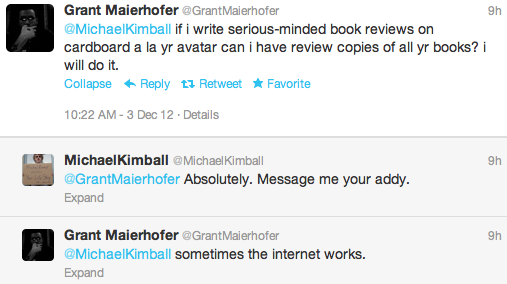

Kimball’s already been discussed, reviewed, and interviewed in and around the online literature sphere, so that’s not what this will be. No. This is the result of one day having opened in congruence Kimball’s Twitter page, and a page of blurbs re: Big Ray. His Twitter avatar is a picture of him holding a cardboard sign that reads MICHAEL KIMBALL WRITES YOUR LIFE STORY (ON A POSTCARD) in promotion of a series of posts on Kimball’s blog where he writes the stories of various writer’s/friend’s in the space allotted by a postcard. The juxtaposition of this and the reviews of Big Ray made me realize: I want to review books on slabs of cardboard exactly like that, but weirder, maybe.

I tweeted to Kimball about the possibility (see below) and, solid dude that he is, he obliged. What follows are those reviews.

There will be two reviews, essentially; the first being a photograph of a large readable-from-a-distance review of the book without any corresponding text below. The second will be a smaller-but-still-fairly-large review of the book on the back of said cardboard with the text transcribed below.

Why the hell am I doing this? I guess from the get go I was never going to write normal reviews of anything. I’m terrible with journalism and essays have always eluded me. At best I can write a decent rant about shit I love, and this seemed an original way to describe art that I’m fond of while not getting too far outside the realm of reason.

March 4th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

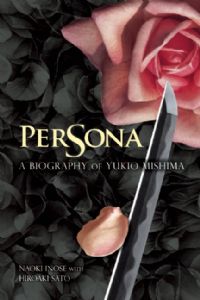

Persona, a newly-released English translation of Yukio Mishima’s biography.

Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

by Naoki Inose and Hiroaki Sato

Stone Bridge Press, January 2013

864 pages / $39.95 Buy from Stone Bridge Press or Amazon

“Perfect purity is possible if you turn your life into a line of poetry written with a splash of blood.” – Yukio Mishima, Runaway Horses

This review—or my interest in the new Yukio Mishima biography Persona coming out from Stone Bridge Press and in Mishima himself—began as these things often do, in a coffee shop with a like-minded friend discussing the rather awesome notion that Japan has a forest devoted almost entirely to suicide. The Aokigahara has associations both with Japanese demonology, and suicide primarily as it’s the second-most popular place on earth to end it all; falling behind in rank to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. I believe the conversation started out discussing the Foxconn suicides and sort of snowballed from there, until mention of Akira Kurosawa’s attempt after the commercial failure of his Dodes’ka-den by me led to my friend’s mention of Yukio Mishima. Unlike Kurosawa, Mishima actually finished the job, committing the ritual act of Seppuku after a failed coup when he was only 45.

I’ve always been attracted to stories like this, as many people—I think–are. Suicide, homicide, sudden outbursts of lunacy by the likes of Jackson Pollock or Norman Mailer have always had a nostalgic twinge for me and I decided then to pursue Mishima’s fiction. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, probably my favorite of Mishima’s books, holds a similar allure to Kurosawa’s cinema, being as it is a contemporary art form describing events long ago made history. His sense of minimalism and terse descriptions of landscapes, conversations, friendships, and the mythological air of Japan in 1400 is like nothing I’ve ever read, and when word of Persona came round, I was certain I had to review it.

I’ve come to expect biographies to fall into two categories if they are in the first place good, or well-written. The first would be relegated to public figures who did not in their lifetime write a great deal or put out some form of art or conversation and hence the biographies tend to concern themselves with familial goings-on, schooling and at-length descriptions of important/pivotal events, and attempted portraits of physical moments in the biographee’s life to create something that’s readable, and fits into the mandates of a narrative the public can enjoy/become informed from. The second is for everyone else; the artists, writers, conversationalists and politicians who made no quarrel with sharing their views with the world and were gleefully recorded by an adoring, or deploring, public.

Persona, as it is a portrait of an actor, an artist, a poet, a playwright, a film director, and any number of other things in the political arena who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature not once, but three times, falls somewhere between these two templates for an enjoyable, and effective portrait of the man.

February 25th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Exodus; an interview with Lars Iyer

What Lars Iyer has managed to do in his trilogy, spanning from Spurious, through Dogma, and now to Exodus—the final book soon to be released from Melville House—feels rather unprecedented. At once these are individually these brilliant picaresque novels ambling through Europe and America; as well as idealistic conversational pieces between his protagonist, Lars, and his counterpart W. Perhaps my favorite aspect of Iyer’s work is the brilliant ways in which he’s able to meld the artists and thinkers of yore, with those today—weaving long conversations about Kafka seamlessly with those about filmmaker Bela Tarr. I’ve loved these novels, and watching them form an official trilogy has me ready to start right over reading them, or anxiously await Iyer’s next effort. I had the opportunity to ask Lars Iyer several questions upon the release of Exodus. We discussed many things, from Nietzsche to Pasolini, and Iyer was prolific in his responses.

What Lars Iyer has managed to do in his trilogy, spanning from Spurious, through Dogma, and now to Exodus—the final book soon to be released from Melville House—feels rather unprecedented. At once these are individually these brilliant picaresque novels ambling through Europe and America; as well as idealistic conversational pieces between his protagonist, Lars, and his counterpart W. Perhaps my favorite aspect of Iyer’s work is the brilliant ways in which he’s able to meld the artists and thinkers of yore, with those today—weaving long conversations about Kafka seamlessly with those about filmmaker Bela Tarr. I’ve loved these novels, and watching them form an official trilogy has me ready to start right over reading them, or anxiously await Iyer’s next effort. I had the opportunity to ask Lars Iyer several questions upon the release of Exodus. We discussed many things, from Nietzsche to Pasolini, and Iyer was prolific in his responses.

***

GM: When it was decided that this interview would happen, I went to check your blog for any updates and found the first entry to be an interview excerpt of Pasolini. Your work draws comparisons from fields far outside the immediate realm of literature—speaking here both of philosophers and filmmakers, comedians and old scribes—so I was wondering about the other side of things; as a writer, how do you address the taboo notion of influence? Do you see the influence of a filmmaker or philosopher as distinctly different than that of a write you greatly admire?

LI: You refer to quotations by Pasolini I excerpted on my blog. I put up quotations of this kind from all manner of sources – from film directors, artists, philosophers, writers and so on – anything I find intriguing, anything encouraging or ‘true’ in some sense. I quote from those I take to be allies – friends of a kind, who I imagine stand with me against common enemies. In this way, I try to spur myself on, especially during those dry periods when I can’t think of anything to write in my own name. The field of endeavour of those whom I quote are of little consequence in this regard – film, art, philosophy, literature – I’m looking only to be enlivened, for an axe to shatter my frozen sea.

How would I address the question of influence? One temptation, in speaking of the works of those who have meant most to you, is to give a narrative – of having read this and then that, of having incorporated this lesson and then that one – without considering how the texts in question transformed your methods of narration, and your ability to construct a coherent narrative regarding what was important to you. There is the risk of rendering linear and personal what is a much more complex reality, in which linearity and the very notion of the ‘personal’ are open to question.

Let me make this concrete. There was a time when lyrical works appealed to me, and lyrical ways of recasting your experience. So I wrote in a lyrical mode, of things that would allow of lyrical treatment. I took various lyrical writers as exemplars. As I grew older, overwhelmed by a world that seemed ill-fitted for such treatment, these modes seemed lifeless to me.

A Portrait of My Failures as a Critic

“Every book in the world is out there waiting to be read by me” – Roberto Bolano, The Savage Detectives

2012 took forever. Moments came and went when things seemed exciting or new or whatever, but all in all it was a long year filled with strange decisions and I came out of it with a pile of books that I’d either ordered late at night because I’d been struck with some desire to “know completely the works of Slavoj Zizek” or that I’d agreed impulsively to review a tome describing the life of such-and-such Avant Gardist because I liked the idea of discussing literature at length in a “public” arena like HTMLGIANT.

Because of this strong desire to be as well-read as possible, balanced against the harsh reality of not having enough fucking time on my hands, there’s now a plethora of things I haven’t finished, haven’t fully reviewed, or haven’t begun to understand that sit on my shelf that—although I can easily discern their respective merits—I can’t see having the time for in the foreseeable future. As a result I’m going to review them, or review their covers, or review their quotes, or whatever; as a collective mea culpa while perhaps discussing the rigors of ambition/the insurmountable plague that is my laziness.

On the surface, this is a lazy approach to make up for my being a disorganized moron; however when I look at these books and think of where I was when I threw my hat into the ring to review them I understand that there’s a bit more to it than that. As a reader—especially a young reader—I think it’s tempting to hope for some sort of Johnny Neumonic device that allows all of Tolstoy or Perec or whomever to immediately flood my consciousness. If this weren’t such a temptation, no living human would ever walk out of a bookstore with more than five books; and yet I typically see those favorite bloggers or writers of mine on the internet citing their interest in more like ten, or fifteen books that they’ve just picked up or received in the mail. As a result I have to believe that on occasion the proverbial/collective eyes are trounced by the collective stomach, and as readers we constantly have to face the guilt of not yet delving into certain editions that loom over us like aggressive schoolteachers.

I admit my problem at the outset. I have no trouble saying “mea culpa” and moving on to think about another review of “Big L’s lyrics” to cheer myself the fuck up. Living is bullshit. I think we’ve all discovered this for the most part and it shouldn’t come as a surprise when I say that in said “living is bullshit” frames of mind the last thing I want to do is read a book for review. I want to watch TV, or read Jim Thompson, or fuck off into the confines of my stupid head for a couple of weeks and completely shirk my duties; and yet for all that self-assuredness in my decision(s) to put off a review another week or so, we have the guilt.

January 16th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Seven Parrots

The Parrot series, published by Insert Blanc Press, was much like its imprint started in a mess of pleasant confusion—my understanding is Insert was at first largely a fake press, that slowly became real—in that prior to the actual writing of each Parrot chapbook, they were simply descriptions of (fake) books by (real) authors to include in the entire fiction that is Insert Blanc; however, after a time, the authors of the (fake) descriptions of the Parrot books were asked to actually write them. What the real story is exactly I’m not particularly concerned. I received seven of the Parrot chapbooks—8-14—and for the past few weeks I’ve carried them around in my backpack, taking one out at random when a moment presented itself for a brief dose of whimsy and entertainment, and what follows will be my perceptions of each of them commingled with anything else I have inside my head upon reading.

Also, I’d like to note as an aside the mere pleasure of a well-made chapbook brought along with your other essentials day-to-day. These Parrots are very well-made, pleasing to look at, to hold, to flip through or to sit down mulling over as seriously as your favorite paperbacks. They call to mind not the muddled shelf of desperate/overwhelmingly-similar zines at any record store on the planet, but a sturdy, comfortable nook in a café where people actually give a shit about reading and are curious about the potentialities of language. Anyway, I digress, but really, I like these books a whole lot.

PARROT 8 ‘I Fell in Love With a Monster Truck by Amanda Ackerman’

As I was reading this, I began seeing a hunched decrepit figure in the periphery of my right eye, and it was terrifying so I stuck to the narrative at hand and by the time I was done the figure was gone, so that was good. I don’t want to use the phrase “prose poem” for as long as I live—quotations aside, I guess—so I’m not going to do that here but that’s kind of what this one is. These are chapbooks of poetry, in so many words, but this one reads like a brief Beckettian memoir of a young person who’s constantly being given workout advice at very inopportune moments and cannot fit through doors and constantly refers—as a Bartleby, of sorts—back to the phrase ‘I WILL NOT PROFIT FROM THE SUFFERING OF OTHERS’—and as a person on a couch reading this I realized that the title mattered in an indirect way but the guts and the language of the thing were compelling and confusing and intriguing and I kept reading—I like to think at the pace of the author while writing it, altogether manic and piling atop itself in fits of hilarity—and by the time it was done I knew I’d read a portrait of some life somewhere and that was good, too. Also, the Keith Haring-esque drawings throughout complimented the work better than most drawings throughout poems/stories tend to do; which is to say, they often don’t (do not) and perhaps only work 23% of the time…

December 17th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Critical Analyses of Big L’s Most Sexually-Charged Lines

“Talkin’ bout ‘rhyme for me, L.’ Man, fuck rhymin’, cos my dick is hard enough to cut diamonds.” Clinic (Shoulda Worn a Rubber)

The diamond is commonly known one of the hardest materials on earth found in any natural deposits. I think lately people have engineered or found stuff that’s harder, but for argument’s sake let’s say the ‘diamond’ is the hardest material known to man. Big L is experiencing such a heightened state of arousal that his cock is now hard enough to cut through the hardest material known to man. Unbeknownst to the listener is whether L himself ever used said member to copulate with the pursued female partner, Joelle, earlier in the storyline. If he did, she almost certainly suffered terrible wounds and lacerations and has since been rendered unable to conceive, let alone experience a true orgasm. It truly makes one wonder about how far rappers are pushed to perform sexually by fans and “groupies” and whether L’s insatiable demon peen didn’t in some way lead to his demise. (He was shot, right? Maybe his diamond-esque sword in some way became magnetic to bullets? One can never be certain about these things.)

P.S. Big L does not want to “rhyme” for Joelle because unfortunately he’s become terribly preoccupied by anything but sex and hence will not be able to do or think about anything but until satisfaction has been reached.

“I knocked the boots from New York to Santa Fe, and that bitch burnt me like a gamma ray.” Same song, later on.

Now here L has set aside his scruples and become cantankerous in the face of a sexually transmitted disease, and though his previous chivalry has put him into this situation with Joelle, it’s now been cast aside in disgust due to that pesky predator, “Gonorrhea.” However, it seems prudent to note L’s ability to boast about knocking “the boots from New York to Santa Fe,” and admit with full candor in the following stanza that he was “burnt like a gamma ray.” Such emotional honesty balanced against stoic egotism has assuredly not been felt since Norman Mailer’s Advertisements For Myself and here we not only have the author’s pants down showcasing his manhood in all its infected glory, we have a protagonist so afflicted by circumstance that the only response he can summon up is a quick, Shakespearean revenge plot. L asserts, “Yo I’mma kill that bitch, next time that I see her,” and it’s not since the Bard that two star-crossed lovers were faced with such unfortunate miseries.

“Fuck around you’ll find my silk boxers in your mother’s hamper.”

Big L & Jay Z Freestyle

Here we return to the themes of old in which the young, spry Big L feels certain that if anyone should have the gall to challenge him or affront his person in anyway, he’ll bed their mother almost instantly. So instantly, in fact, that the proverbial you—a young man equally spry though perhaps not quite as sharp, and what’s more you often dig through your mother’s hamper (?)—will soon find L’s “silk boxers in your mother’s hamper.” This is the ultimate revenge story because the tragedy for the victim occurs long after the fact. Will you walk in on L with his hands cascading anxiously over your mother’s supple flesh? Will you see them at Denny’s late one night after seeing Liam Neeson’s newest picture? No. You will be left to stew in ignorance and curiosity as to whether these boxers, silken and inscribed with the man’s name, could possibly have reached your mother’s hamper through the depraved acts of which you dare not speak. READ MORE >

The Nervous Breakdown’s board

board: voices from the nervous breakdown

board: voices from the nervous breakdown

by brad listi & justin benton

TNB Books / November 2012

246 pages / $15.95 Buy from Amazon or Powells

I recently purchased that massive Paris Review Book of Absolutely Everything Under the Sun (that’s not really what it’s called, guys) because of a handful of entries I’d rather read on a printed page than on The Paris Review’s website, and it was delivered to me at just about the same time I received a review copy of Brad Listi and Justin Benton’s board, a work of literary collage “derived entirely from comment boards at The Nervous Breakdown website,” and for a split second there I really relished the thought of reviewing the two in congruence: reading an entry from The Paris Review and then, say, five or ten pages from the TNB book. While the thought still strikes me as appealing, I can tell in the first thirty or so words of board that I’m not going to want to pick it up and put it down so repeatedly because the words carry every freshness of good personalized poetry, and the Paris Review Book of High Hopes n’ Dick Jokes Ad Infinitum strikes me as desperately boring in comparison.

Anyway, moving on. To my mind this is an unprecedented literary endeavor. A published collection devoted entirely to the commenters and loyal fans of a literary website in the form of their comments. The book begins with what one can assume is the result of a prompt like, “What was your earliest memory?” and as the results pile up and “nest” (the indentation as comments amass on sites like this, I learned in the Author’s Note) I realized I was witnessing a sort of new literature and art created in a way I’d never think possible. It’s as if Studs Terkel’s Working were condensed and piled up with—loosely—guided prompts and topics of discussion and yet for all this book’s digital initiation and contemporariness these entries are beautifully, often poetically written with an honesty you aren’t going to find on socialized pyramids schemes like Youtube or your overtly—and miserably—political best friend’s Facebook feed. Each moment, be it a combined dissertation on the collective childhood memories related to the Incredible Hulk or a seemingly random aside like “I murder every single bug that crosses my path,” is absolutely the stuff of literature.

I find it interesting/compelling that one of the quotes on the back of the book is given by Jeff Ragsdale, author of Jeff, One Lonely Guy who posted flyers with his number all over New York City and compiled a similarly-minded book that was the result. He lets people vent profusely in the phone calls and emails and messages that lead up to the finished book, and that same honesty—that same abandonment of concern and worry—is like a nervous system running between Jeff and board that causes both to permeate with energy and humanity in a mode I haven’t felt in good novels or poetry for quite some time.

December 3rd, 2012 / 12:00 pm

All Love is Lunacy: A Review/Interview with John Toomey

Huddleston Road

Huddleston Road

by John Toomey

Dalkey Archive Press, October 2012

160 pages / $15 Buy from Dalkey Archive or Amazon

John Toomey’s first novel Sleepwalker was an expertly cynical debut; something of a sprawling segue into Dublin as it’s then to be known to the reader and its excesses are as hilarious and compelling as they are cutting and insightful. That book is essentially what I think of as a hedonistic pipe dream put down on paper with nothing held back, with all the literary savvy of any of the contemporary masters describing chaos in the city, while retaining an originality that’s marked Toomey as an important presence in contemporary Irish literature.

His second book, Huddleston Road, is first and foremost a departure from that cynicism and mania inherent to the first. I’d argue that fans of the first book will immediately know the author’s work when they begin reading his second but the shift away stylistically is undeniable; and quite impressive. Consider, for a moment, the first books of Jay McInerney, or Bret Easton Ellis, each American authors who began with dark comedic forays into metropolitan chaos. One could argue that McInerney has grown away from this over the years but he’s always retained some of that sensibility, and the same certainly goes for Ellis, ten-fold. Although I’m a tad hesitant to draw comparisons to the first books of either of those writers (of considerably different movements than Toomey) the general point I’m hoping to make is that the writer challenged himself in starting out with such a distinctly-crafted epic as Sleepwalker, and—all the 2nd novel mythos aside—Toomey has managed to show here a different set of literary chops, while retaining the maniacal attention to detail so prevalent in the first book.

It follows a young Irishman named Vic. Vic leaves Dublin for London early on in the novel and through no real preference of his own winds up teaching history and such to teenagers. Again, through each moment, each paragraph, each sentence, the importance of this book seems to be that wild attention to detail Toomey seems to have great control over. A young man standing at a party is never simply that, but an opportunity to explore the ramifications of standing at said party and the physical details of those present and the questions running through young Vic’s mind. At times it reads as a sort of summary of this character’s thoughts and yet the vivid moments of dialogue and scene give striking reality to each moment when you find yourself so ingrained in this character’s reactions to moments that you forget the moments themselves.

Because this will also be an interview, and because I’m hardly interested in giving a moment-by-moment account of the novel’s content, I won’t delve that much deeper into the goings on in Huddleston Road except to address perhaps the most important part: Lali. Lali is a girl Vic finds himself desperately attracted to with every moment that passes. She doesn’t seem interested and even acts like a bit of an asshole at first and yet this draws Vic slightly more to her so that when he’s finally given a chance to sit and speak with her his mind is torn asunder with thoughts and worries and chaos and yet he cannot help himself. This is, I’d argue, a love story. There are moments that make it considerably different than most love stories you’ve read and will read, but all the same there are tropes at play here that make this book a fresh spin on the old magic of two people falling in love in spite of terribly difficult circumstances, and the ramifications in both of their lives as a result of this.

November 19th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

BOOK OF KNUT: A NOVEL BY KNUT KNUDSON

BOOK OF KNUT: A NOVEL BY KNUT KNUDSON

BOOK OF KNUT: A NOVEL BY KNUT KNUDSON

by Halvor Aakhus

Jaded Ibis Press, Forthcoming Fall 2012

270 pages / Buy BW Version ($10-12) or Color Version ($28-33) from Jaded Ibis Press

I recently inhaled Halvor Aakhus’s BOOK OF KNUT: A NOVEL BY KNUT KNUDSON, and admittedly—considering the galleys I received are technically in PDF form and I simply couldn’t help myself—I also began by listening to that DJ Exotic Sage Presents: Blood Orange Home Recordings Mixtape and watching Jiri Barta’s ‘The Club of the Laid Off,’ and interestingly enough had no real problem paying proper attention to the book; it’s that fucking hilarious.

I sat on my couch letting my focus shift more and more into the novel, letting each corresponding media fall ever quieter as I tore deeper into the strange tale of a mathematician reading through the aptly-named Book of her now-deceased former-lover (he left her for her mother, as I understood it) Knut Knudson; and with every passing page I’d belt out another howl of laughter at the sheer brilliance and magnitude of this absolutely fucking insane narrative.

The actual book—Book—for all its strangeness and insane devotion to detail, is equally as enticing and, I daresay sentimental involving characters like Johnny Potseed, a guy who’s walked around the town of Napoleon, Indiana for 10-plus years throwing potseeds “to no avail…thus far,” and a fired mathematician (representing the cuckolded daughter’s cuckolding mother) named Slob—Slobodon—who organizes a late-night Christmas Tree planting to spite the university from which he’s been fired. The entire scene essentially thriving on minute details in weather and each participant’s academic pursuits, and ever-present cans of Keystone. Other irreplaceable namesakes include Mop, and Wolfer. This dude (who, by the way, looks like a Norwegian metal head that just walked off the set of Deliverance) is definitely onto something.

READ MORE >

November 5th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Needing Don DeLillo

“A writer takes earnest measures to secure his solitude and then finds endless ways to squander it.”

– Don DeLillo, The Art of Fiction, The Paris Review No. 135

The following is a discussion of the world and effects of the works of Don DeLillo. The books focused on are chosen more by my emotional state than by pragmatism, however all of his works will make an appearance at some point. The assertion here is both personal and universal, stating that Don DeLillo changed my life, and gave new breath and scope to the world of literature.

Don DeLillo began writing later than many the American prodigy to change the movement of our country’s letters. His first novel, Americana (published when he was roughly 35 years old)—a winding tale of one man’s devolving lunacy reflecting a life of advertising, television, and travel—to hear him tell it, came from a quick sight of a man standing on a road staring off at nothing, that brief vision was enough to carry him through the beginnings of his first novel and, in light of that, the early stages of what has been one of the more tumultuous careers in history.

When the idea came to me to write about Don DeLillo for HTMLGiant, it was first slated to be an exploration of his novels Great Jones Street and, ideally, White Noise—comparing something less-discussed to something hailed as one of the masterpieces of the latter half of the 20th century; what fueled this? What brought about this response? Etc. etc. etc. ad infinitum. However, I found myself unable to hold back certain instincts as I began to reflect over his impact on me and this world as a whole, and in spite of myself began falling deeper and deeper into a DeLilloan stupor with every interview, novel, and anecdote explored. I found the intricacies of his books that I’d call my favorite proved far less ambiguous than I’d thought and that–say, with the discussion of contemporary (in 1985-ish) universities in White Noise–his work was sewn deeper into me than I’d realized.

There was, I think, initially an aversion to his writing due to the fact that the only copy of DeLillo’s work we had in my house growing up was a very daunting paperback of Underworld (interestingly, I was only completely drawn back to it when attempting an essay on the Spaldeen, a little Hi-Bounce Ball made by Spalding that I’ve become quite obsessed with that DeLillo notes in the novel, as they were the primary ball used in stick ball games in New York City in the heyday). I remember picking it up one day after reading Bret Easton Ellis considered him a great influence and finding myself lost beyond salvation. The words didn’t exactly register and when they did they seemed strange, infused with a level of what I’d now call reified Americanism that wasn’t apparent in anything I’d been reading at the time (Ellis, Fante, Kesey, et al, authors of fiction that seemed to be right there, which I found in DeLillo only after reaching the necessary level of paranoia to understand the first book of his I read and loved, Mao II) and in spite of a burning curiosity, I tucked the paperback where I’d picked it up on the shelf to remain for several years until I found those radiant little pink Spaldeens in a hardware store in Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

October 26th, 2012 / 12:00 pm