No Thanks: A Simple Wish for the Ends of Alt Lit

Last week I watched Nathan Staplegun eat salted peanuts on spreecast. What started off as Nathan eating salted peanuts soon turned into Nathan asking his roommates or friends (and thus turning the computer camera in their direction) what they were preparing in the kitchen, and quickly became a spreecast showing one of Nathan’s online friends playing guitar. On the surface, Nathan Staplegun eating salted peanuts on television (that’s what platforms such as spreecast are: do-it-yourself TV) would seem like a snooze, a no-brainer, an excuse to read more books. But, what Nathan did was really great. He put on TV a thing that he would have done anyway and by doing it on TV turned the act of eating salted peanuts into something else: an event, perhaps.

I love to tell the story of Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party. In 1978, Glenn O’Brien and friends (and his friends were people like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Amos Poe, Deborah Harry, Walter Steding, Chris Stein) got together and decided to take advantage of public access cable television in New York City. The format was simple: hang out with friends, get high (one episode had Fab Five Freddy in costume teaching viewers how to roll perfect joints), have your friends play music, and talk to people (viewers called in live while the show was on air and used their short time to make death threats and complain about how shitty the show was). By television’s standards, the TV Party shows were shitty, but they were fun to watch. And, in their own way, became increasingly popular (special guests included David Byrne, Klaus Nomi, and Mick Jones of The Clash) and influential (in one of his early top ten lists David Letterman cited TV Party as an influence). Art and everyday life will never be separate things; although, the art marketers sure seem to want us to believe that they are. Friends get together, record each other doing silly things, or someone we hardly know broadcasts himself washing dishes or whatever, and art’s possibility is renewed, if not, realized.

The word ‘creepy’ has not always had negative connotations. Vito Acconci follows people around New York City as part of his month-long performance ‘Following Piece’.

I have been kicking around the idea of starting a series of posts in which I cruise my facebook friends’ facebook photos and post the ones I like as part of ‘Creeper: Favorite Facebook Photos of My Facebook Friends’. The word ‘creep’ (and its variations) has not always had negative connotations. When Radiohead hit the pop charts in 1992 with their debut single “Creep” the song seemed like a strange, wonderful call to embrace the pathos of a loser, a lost subcultural weirdo whose dreams and desires are too much for himself and the world. Much like Beck’s “Loser” the song seemed to reinvigorate a long-standing yet dangerous tradition in the arts: the elevation of the low, the loser, the outsider, the emotional clown, to the status of cultural barometer, of artist. Long-standing because American cultural producers had carefully exploited this type for profit since the early days of white rock ‘n’ roll (Elvis Presley) and the first teen films (Rebel Without A Cause). Dangerous because sometimes people actually believed in these characterizations enough to begin to act like rebels, not satisfied with merely listening to them on the radio or watching them at the movies.

It’s not Dennis Cooper’s male escorts of the month. It’s The Bad News Bears (1976), who demonstrated that life sometimes artfully happens when a bunch of losers get together and push the game to its limits.

In 1969, Vito Acconci made art by simply following people around New York City. Acconci spotted someone on the street and followed them until they disappeared into a place he couldn’t, or didn’t, want to go. Acconci’s performance lasted almost a month. He’d get up, go outside, spot someone, and follow. Most spreecasts, for better or for worse, go on way too long. But, so does hanging out with one’s friends. At some point, you want to be by yourself or hang out with someone else. With the advent of the spreecast you can hang out with people you know or don’t know or want to know simply by joining in. It’s the logic of the club but not as restrictive. Of course, hanging out on spreecasts may never beat the intimacy of being in the same room with a friend or a loved one or turning it all off and reading a book. But I’ve known a lot of people who got all the companionship they needed by simply watching episodes of Breaking Bad or whatever–and apparently, according to some, you can be plugged in and still experience solitude.

This isn’t a plug for spreecast, who I could give two fucks about. It is a plug for a kind of art that denies the art market and realizes itself in everyday life. One doesn’t need an important architectural group, a big publisher, and a major museum to support an effort to follow and document people in your neighbor (although Acconci had all of those). One does need ideas. I was talking to Elizabeth Emily D’Agostino in her car about art. We were parked outside my apartment–a perfect venue to discuss anything. Our conversation shifted to cultural amnesia, an easy target. In our desperate efforts to predict the future I described for her a story written by Tao Lin and boldly proclaimed that this was Lin’s crowning moment and that history would look at this moment as an opportunity lost. The story is simple enough:

when i was five

i went fishing with my family

my dad caught a turtle

my mom caught a snapper

my brother caught a crab

i caught a whale

that night we ate crab

the next night we ate turtle

the next night we ate snapper

the next night we ate whale [. . .]

The last line of the story is repeated almost endlessly or as long as the writer/reader can endure it. Although, I have read a version of it where it ends rather abruptly. For a video account of its hilarity, you can listen to Tao read it here.

Why an opportunity lost? Because when an artist with the talent of Tao Lin comes along he seems to come with a two-pronged fork capable of reflecting the zeigeist back to us and/or breaking the hold the zeigeist has on our attitudes, desires, fashions, discourses, etc. In the post-Warholian world in which we live contemporary artists have made it clear that they are more interested in and perhaps more capable of showing us who they are (i.e. reflecting the ‘zeigeist’ back to us) than breaking the mirrors that bind us to a social-medial and political-economic worldview that reinforces the notion that ‘we’re fucked.’

May 1968, France. Today, the attitudes and aspirations of the ‘me generation’ of the 1970s have resurfaced in the attitudes and aspirations of millennial artists.

We are fucked. In Sheila Heti’s novel, How Should a Person Be?, someone comes up with an idea for an ugly painting competition. I say ‘someone’ because not even Sheila, our narrator, knows who came up with the idea. The idea of making the ugliest painting is more difficult than you’d think. Relationships are ended, lives are changed. During the height of the national crisis that was punk rock in England in the 1970s, a roadie for The Who dismissed the movement as a mere ‘revolt of the uglies.’ I mean, imagine calling a bunch of teenagers parading their misfortunes, economic hardships, childhood traumas, bad skin, social awkwardnesses, and fashion made of actual garbage found in the street as revolting or, worse, ugly? It is with these two sentiments in mind–a conceptual call to ugliness in the name of something else (Heti) and its celebration as an insult (punks)–that I invoke the writers and artists of the alt lit movement, a movement that has come to signify everything that’s right and wrong about everything that’s fast, cheap, and out-of-control in the arts today. Perhaps the time has come to break the mirrors that bind us to our own little personal victories (i.e. ‘I’m internet famous’) and begin the more fun and difficult work of smashing those fucking mirrors so that we–and the big, bad world–may see ourselves again, as something else, something more, something seemingly uglier and thus, perhaps, more beautiful. Of course, you could choose to ignore me (I’m used to it, really)–your career path probably profiting more from it–than listen to me whisper to you, from the salted peanut gallery.

@janeysmithkills

kottonkandyklouds.tumblr.com

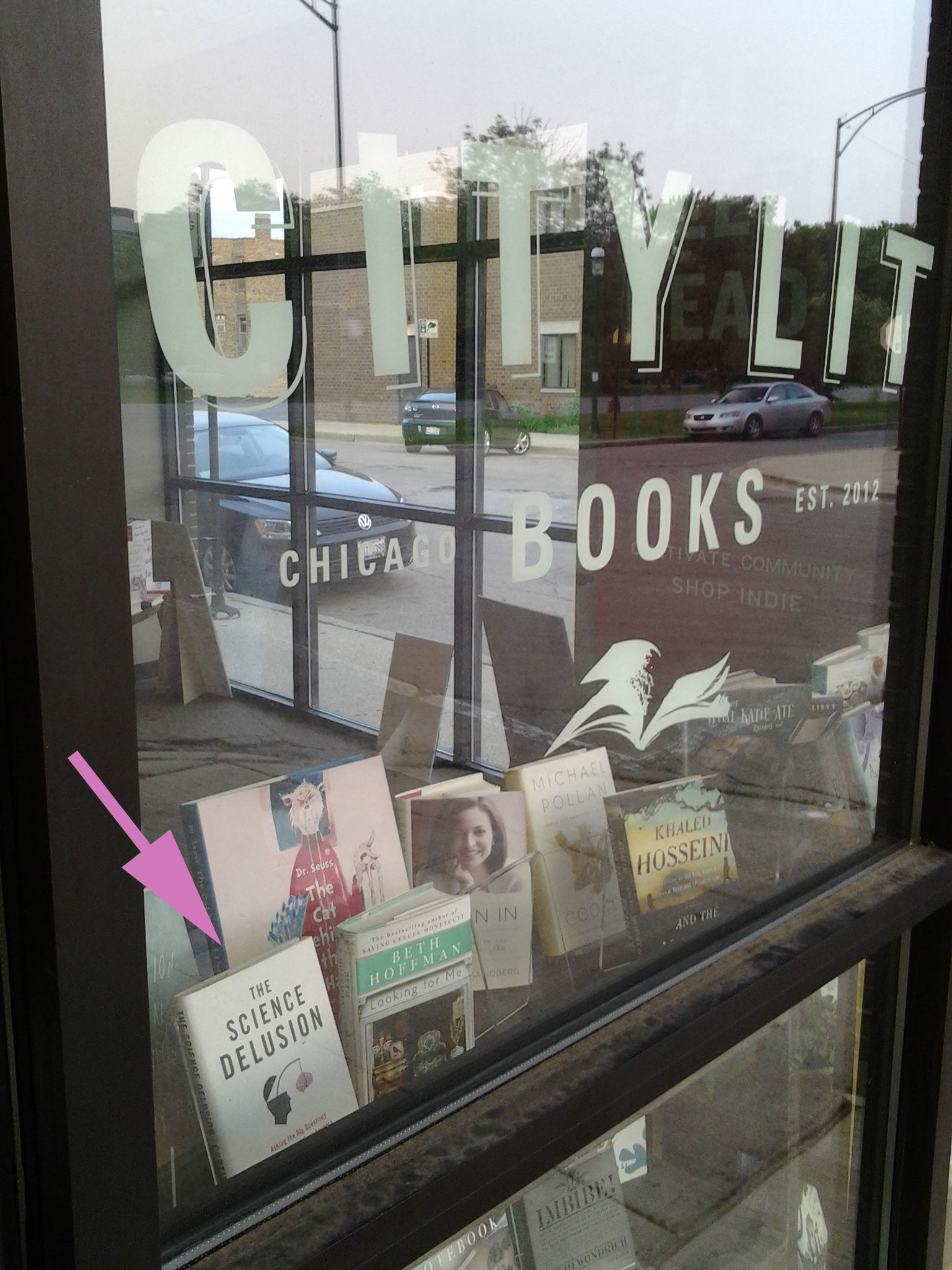

Curtis White will be reading in Chicago this Thursday

At City Lit in Logan Square, at 6:30pm. Curt will be reading from his new book, The Science Delusion: Asking the Big Questions in a Culture of Easy Answers, which just came out through Melville House.

I did my Master’s degree with Curt at Illinois State University, and he’s one of the smartest and best writers I know. (He’s one of the two profs who first got me reading Viktor Shklovsky.) In the 1980s, he and Ron Sukenick transformed Fiction Collective into FC2, and I learned about FC2 (and ISU) partly through the two “sampler collections” they put out (something I wish more presses did). Curt’s also written seven works of fiction, including The Idea of Home and Memories of My Father Watching TV, and now five works of nonfiction, including his infamous attack on Terry Gross (among other things), The Middle Mind. (He may not have made Gross cry, but he sure pissed off a lot of her fans.)

I’m only halfway through this new book (and will be writing more about it later), but so far I’d describe it as an attack on the idea, currently very en vogue, that scientific knowledge is the only or most superior form of knowledge, and thus the only means of accounting for what it means to be human. Right from the start Curt shows how much of science’s own knowledge is shoddy and unexamined. For example, it’s not uncommon to hear scientists like Stephen Hawking claim that the universe is beautiful, but how do they understand beauty? Not very well, Curt argues. Like in The Spirit of Disobedience, Curt demonstrates how other intellectual traditions—specifically Romanticism, which he traces through the Beats and punk—offer a way around and past some of the more inane debates consuming so many today, such as “science vs. religion.” Plus he’s funny, too.

If you’re in Chicago this Thursday, come by and hear Curt! Discussion will follow during which you can ask him embarrassing questions.