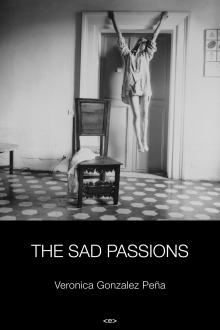

The Sad Passions

The Sad Passions

The Sad Passions

by Veronica Gonzalez Peña

Semiotext(e) / Native Agents, May 2013

344 pages / $17.95 Buy from Amazon or MIT Press

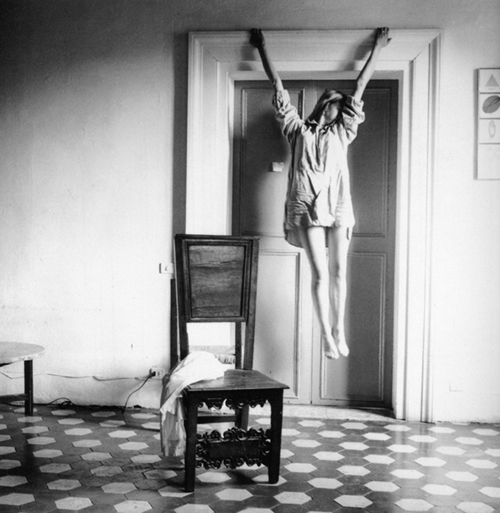

The cover of Veronica Gonzalez Peña’s novel, The Sad Passions keeps changing on me. It’s a Francesca Woodman photo—a woman or an apparition. She is suspended in air or hanging on for dear life. She is a martyr or a demon. She is in pain or in the realm of the sublime. She is being crucified or being exorcised or being made a martyr. I keep approaching the possibilities of this puzzling image and watch the figure grow porous the longer I look. She is an unstable subject and as I make my way through the novel, it’s the chair that grows more present, more formed than the person. Something in it’s gaping emptiness, the carelessly draped cloth suggesting a body, now gone. I like the way the image moves with this novel, the way the absence becomes the presence. Veronica Gonzalez Peña does not write absence as a form of lack, her absence froths and grows agitated, it fills up the page with pulsing need.

The Sad Passions follows four sisters, their lives punctuated by their mother’s mental illness, by an inheritance of cumulative ancestral pain. The sisters, while distinctly different from one another, all grapple with the fear that their mother’s madness might become their own, that their identities might slip quietly, at any trigger. One gets a sense that at the turning of the page one sister might become the other or that they might all become their mother or they might all melt into a composite figure.

It’s precisely this plurality, this repetition/duplication of identity that is at the center. In a chapter told from the perspective of the 2nd eldest sister Julia, Gonzalez Peña writes,

Each chapter is told from the perspective of a different character, often retelling the same traumatic events but with startling different sentiment. There is something in the retelling process, the approaching of truth by making different angled entries but never quite locating truth, dancing towards it—if only to say that understanding trauma, by nature is a process of de-centering, that understanding must be choral.

August 12th, 2013 / 11:00 am

An Arab Melancholia

An Arab Melancholia

An Arab Melancholia

by Abdellah Taïa

Semiotext(e), March 2012

141 Pages / $14.95 Buy from MIT Press or Amazon

In consideration of the memoir, or autobiographical non-fiction, It could be said that I take issue with the genre. Generally. As a mode of writing, the market tends to be overrun by a multitude of examples of the dominant narrative—that of the straight white man—and when the Other breaks into the limelight of that best-sellers table at your local Barnes & Noble, it’s generally within the context of a very approachable, almost white-washed context. Books for the middle-class to buy and read and convince themselves that they know about the world. I realize this might sound unduly harsh, but my experience has lead to the building of this experience, whether it’s fair to the publishing world as a whole or not.

I think that Semiotext(e) demonstrates an awareness of the shortcomings associated with the overarching title of “memoir”—instead of using the term in any of their press materials for Taïa’s book, the term “autobiographical novel” is used. This is an important semantic justification, in that it removes the book from the context of the zeitgeist that it would immediately find itself outside of.

But perhaps form follows function, as Taïa himself is a gay Morrocan writing explicitly about his experiences. Not only is he doing this, he also seems to be the first “openly gay autobiographical writer published in Morroco.” This is honest writing from a marginalized position.

In her article, “Experimentalism, Why?,” Camille Roy offers the suggestion that ‘experimental’ writing, being inherently marginalized, is a perfect mode of writing for the marginalized writer to explore. Taïa’s prose is ostensibly straight-forward—he eschews linearity, sure, piecing his narrative together by presenting fragments of the past out of order—but the language itself displays characters (people) in conflict, events, dialog, psychological insight. And there is, in this case, nothing problematic about that.

The novel begins by invoking Taïa’s childhood, and importantly, offers an incident which immediately removes Taïa, as the first-person narrator, from the conext of the ‘victim,’ particularly vis-a-vis his homosexuality. Considering that the rest of the book addresses, ostensibly, a break-up that marks Taïa far more than he’d like, this is a wise textual move. It refuses the reader the opportunity to develop a sentimental empathy; we cannot pity Taïa because we know he is strong—his sadness is a considered sadness, a larger issue than simply the immediate frustration encountered when facing the reality that YOU love someone who does not love YOU back. This is a symptomatic melancholia, the vague opportunism of the world when it encounters someone (our narrator, Taïa), who stays stubbornly romantic.

The tableau offered to launch the book offers an almost ecstastic holiness, a self-considered realization, a contra-monde mode of being decided early-on in youth—an ecstasy interrupted only by death. A death of the self, both literally and metaphorically.

Death haunts the book, or perhaps just that unknown that we call death when no other language seems adequate. An accidental electrocution, a wavering plane, the crushed spirit. Taïa pulls through all of these paroxysms with a renewed will, a hope, a decisive intent. Perhaps this is not the best narrative to inject into middle-America’s current “It Gets Better” campaign/obsession (problematic in its own right). But this reality is what the book leaves with its readers; an insistence that through everything there is always something else that follows. It’s neither a hesitant optimism nor a beaten-down acceptance, a nihilism; it’s something else, something more human. The weight of the world cannot be taken on as the Sisyphean boulder, but rather we have to just forget about the world and make sure we’re moving forward.

March 29th, 2012 / 6:59 pm

REVOLT, SHE SAID

Where Art Belongs

Where Art Belongs

by Chris Kraus

Semiotexte, 2011

160 Pages / $13 Buy from MIT Press

&

Girls to the Front

by Sara Marcus

Harper Perennial, 2010

384 Pages / $15 Buy from Amazon

If you’re invested in the lives and work of girls as cultural agents, then you’ll like Sara Marcus’ Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution and Chris Kraus’ Where Art Belongs. Like certain of my punk obsessed friends, my interest in bands like Bikini Kill and Bratmobile developed in high school during the late 90s. And by then the whole riot grrrl phenomenon in its original incarnation, with Kathleen Hanna front and center at the mic, was more or less dead. By the time I was introduced to Bikini Kill’s first album, the band had already released its final album Reject All American and played its final show in April 1997. Subsequent fans were left to speculate on both the political origins of the band and the interpersonal relationships that constituted riot grrrl as a living, breathing feminism.

September 19th, 2011 / 12:00 pm

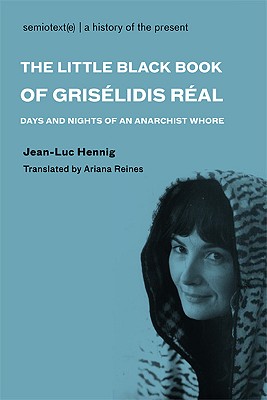

Ariana Reines Week, Part 4: The Little Black Book of Griselidis Real

We began Ariana Reines week with AR’s original translation of Baudelaire’s My Heart Laid Bare, published through her own press, Mal-o-Mar Editions. Now, after two days cavorting with Dan Hoy and Jon Leon, whose split book (The Hot Tub / Glory Hole) is also new from MoM, we return to Reines-as-translator, and consider a new book from Semiotext(e), The Little Black Book of Griselidis Real: Days and Nights of an Anarchist Whore. Here (from the site) is the briefest of introductions to Real:

Hailed as a virtuoso writer and a “revolutionary whore,” Grisélidis Réal (1929–2005) chanced into prostitution at thirty-one after an upper-class upbringing in Switzerland. Serving clients from all walks of life, Réal applied the anarcho-Marxist dictum “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs” to her profession, charging sliding-scale fees determined by her client’s incomes and complexity of their sexual tastes. Réal went on to become a militant champion of sexual freedom and prostitutes’ rights. She has described prostitution as “an art, and a humanist science,” noting that “the only authentic prostitution is that mastered by great technical artists … who practice this form of native craft with intelligence, respect, imagination, heart…”

The main action of the Semiotext(e) volume is a series of lengthy interviews between Real and Jean-Luc Hennig (a professor at the University of Cairo) but the final section, a hearty selection of entries from the titular Little Black Book are not to be missed. They are the concise, practical, hilarious, and delightfully NSFW. Click through to read some of my favorites.