Web Hype

A Tale of Two Jennifers

Jennifer Egan had a pretty great week last week. She won the Pulitzer for her novel The Goon Squad and the news broke that HBO optioned her work for a television series. Then she did an interview with the Wall Street Journal, an interview I read and thoroughly enjoyed. She talks about winning the Pulitzer, fielding the usual questions one might get about how it feels to receive such recognition, how she found out (at a restaurant as she was sitting down), and a little about the work itself. Because she is a woman who writes, and does so prominently, Egan was asked about gender and how male and female writers come off in the press. The exchange looked like this:

Q. Over the past year, there’s been a debate about female and male writers and how they come off in the press. Franzen made clear that “Freedom” was going to be important, while others say that Allegra Goodman was too quiet about “The Cookbook Collector.” Do you think female writers have to start proclaiming, “OK, my book is going to be the book of the century”?

A. Anyone can say anything, that’s easy. My focus is less on the need for women to trumpet their own achievements than to shoot high and achieve a lot. What I want to see is young, ambitious writers. And there are tons of them. Look at “The Tiger’s Wife.” There was that scandal with the Harvard student who was found to have plagiarized. But she had plagiarized very derivative, banal stuff. This is your big first move? These are your models? I’m not saying you should say you’ve never done anything good, but I don’t go around saying I’ve written the book of the century. My advice for young female writers would be to shoot high and not cower.

I thought it was a pretty great answer, which may surprise you, but it is important for all writers to aim high, to be bold, to not cower. I am all for anyone who encourages ambition. I did not really give Egan’s answer more thought but then Jennifer Weiner started to talk about the interview on Twitter. I follow Jennifer Weiner. I read Good in Bed when it first came out and loved it. I also read and loved In Her Shoes. I follow her blog. My point is, I’m a fan and have been for years though I haven’t read her more recent work. Somewhere along the way, she became pretty famous and now her name is bigger on the book cover than the title. I am glad to see how her career has taken off. She has also, as of late, developed a bit of a reputation for being outspoken. Whenever someone prominent expresses an opinion they are labeled as outspoken. That label is rarely a compliment. Weiner (along with other writers like Jodi Picoult) had a lot to say when the literary world was agog with excitement over Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom, for example. I get it. The hype was exhausting and disproportionate to the critical attention other writers receive. In this most recent incident, it seems Weiner felt Egan was disparaging “chick lit,” with her response because the books the aforementioned Harvard student plagiarized, those books alluded to in Egan’s response, were from the “chick lit” genre.

Deena Drewis wrote a great essay on the subject for The Millions detailing a lot of the “backlash,” as well as thinking through the implications of this current discussion/debate, the term “chick lit,” and the idea that all women writers should be ideologically unified. I agreed with most of what Drewis had to say on the subject though I’m pretty sure “chick lit” writers didn’t coin the genre themselves. Any debate about that genre, the name of that genre, and how women writers function within that genre needs to acknowledge the origins of the term “chick lit,” as a faulty construct of the publishing industry. Still, I particularly appreciated Drewis’s focus on the impossible expectation of ideological unity. It is rather unrealistic to expect people who share a certain set of characteristics to agree about much of anything. Just because women share a gender and also happen to be writers does not mean we’re all going to sit around sipping tea agreeing about everything. I hate tea, for one.

Interviews are complicated. A friend recently said to me, “Press isn’t what you want. It’s what you get.” I’m pretty sure Egan participated in countless interviews that day, flush with the news of the Pulitzer, probably being asked the same set of questions over and over. I believe she meant what she said but I don’t believe she was being malicious. The backlash surprises me, seems unfair. Egan was being honest, speaking off the cuff. Sometimes our honest opinions are not the most politic. When you’re in a position such as Egan’s I don’t know that there is a “right answer,” when it comes to potentially explosive questions. You cannot please everyone and as evidenced here and there and everywhere, it is quite difficult to discuss gender and [insert field]. I don’t know why Egan is expected to love certain books just because they were written by women. It could certainly be said that she doesn’t have to go out of her way to tear those books down, either, but she doesn’t really do that. She makes one statement and doesn’t name any books by name, and then those of us who read that statement assign all sorts of values and responsibilities and motives to her words.

I’ve read two of the books vaguely referenced in Egan’s interview, Confessions of a Shopaholic and The Princess Diaries. They are wonderful books—warm, witty, and very charming. Are they books I would use in my creative writing class as examples of writing my students should aspire to? No. Maybe that’s a failure of imagination on my part but I like grit in my reading and those books do not have the grit I am looking for. When I think of all the books I love that I want to show students as examples of writing to which they should aspire, I don’t think about a novel about a girl who spends too much money and then has to work her way out of debt, falling in love along the way. However much I enjoyed it, that book doesn’t even come close. The reality is that there are a lot of books and there are a lot of great books. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. A book can be great without being great. Those particular books and the writers of those books are doing quite well for themselves without receiving the imprimatur of the critical world. Isn’t that enough?

Perhaps not.

For the past few days, Zadie Smith’s rules for writers have been circulating the various social networks. Smith’s rules are as sound and intelligent as you would expect. Her final rule states, “Tell the truth through whichever veil comes to hand – but tell it. Resign yourself to the lifelong sadness that comes from never being satisfied.”

Are writers truly never satisfied? The thought that, as writers, we will spend the entirety of our careers trying to be happy while accepting the constancy of dissatisfaction depresses me. But then I think of Jennifer Weiner. She has sold, I am guessing, hundreds of thousands of books, if not more. She is the executive producer of a television show debuting on ABC family this year. One of her movies, In Her Shoes became a major studio film (and a great one) starring Toni Collette and Cameron Diaz. Other books have been optioned and may someday make it to the big screen. I cannot imagine why Jennifer Weiner cares about the critical attention a Franzen or Egan receives or what Egan says about “chick lit.” Until last year I had never heard of Jennifer Egan (whose writing I’m really digging too) but I’ve known about Jennifer Weiner for nearly ten years. By most measures, Weiner has achieved the kind of success few writers will ever know and still, when you see her discussing literary writers and voicing her opinions on “literary fiction,” versus, “chick lit,” you get the sense she is not satisfied despite everything she has achieved. She has built a brilliant career for herelf and still, she wants more (respect? critical attention? recognition for the power of the genre she writes in?). I love that she wants more.

I understand what drives Weiner to discuss these issues and to continue to be outspoken. Jennifer Weiner is actually doing exactly what Jennifer Egan wants young women writers to do, to “shoot high and not cower.” If the two Jennifers sat down and had a drink I’m pretty sure they would find they are not at all far apart in their thinking about women and writing. Maybe they already do this. I imagine all famous people know each other.

It is unfortunate that Jennifer Egan is being held responsible for a complicated issue that reaches so far beyond her statements in one interview, the day she won the Pulitzer. Egan finds the titles a Harvard student plagiarized ten years ago derivative and banal. So what? That’s her right. She is not the spokesperson for women or literature or women writers or anyone or anything but herself and her own writing. Like all of us who are outspoken, she’s entitled to voice unpopular opinions (though I don’t think her opinion is that unpopular). By the same token, people are entitled to react to those opinions.

Getting into a frenzy over Egan’s comments ultimately feels like a complete waste of time. This current backlash is the tempest in the proverbial teapot. Instead, we could (and should) discuss why certain kinds of stories are labeled as “chick lit,” and why those stories and the people (often women) who write those stories don’t receive the same critical attention as writers of “literary fiction” (often men), and how we might change our attitudes toward “chick lit,” and how we might teach young writers to shoot high and not cower. In The Merchant of Venice, Portia says, “It is a good divine that follows his own instructions.” I’m going to try and do that by finding a productive way to use a “chick lit” book in my fiction class next fall. It’s a small step but even small steps eventually get you where you’re going.

Tags: chick lit, Jennifer Egan, Jennifer Weiner

I would be inclined to use both those books (Princess Diaries & Shopaholic) in a writing class as examples of narrators which are funny and charming and which implicitly suggest the reader adopt a position of slight superiority over the narrator (yet still manage to be readable and enjoyable). Readers may relate to certain zany things that Becky Bloomwood and Mia Thermpolis do and say but they’re very much and very consciously larger-than-life characters.

If someone used a “chick lit” novel in a college workshop that I was paying for I would drop the class. I don’t know if that’s because I’m a male or a snob or both or neither.

Also, I find that I don’t have time for books that aren’t great. I just don’t. And I’ll go ahead and judge that within 50 pages.

I’m not so sure. What if it was 10 books (usually what I assign grad students) and ONE of them was lighter. You’d be surprised how it makes students compare and contrast. This is a pedagogy technique, not to elevate the inferior (subjective, etc.) book, but to elevate the critical discussion.

I understand the inclination but I also think it’s short sighted to assume all “chick lit” novels are bad. Such is not the case. The whole point of education is to be exposed (and open) to new ideas and books we might not otherwise read. Now, I have no idea if it will be viable to use “chick lit,” in a writing class, and as I noted early in the essay, there are just too many books I love more to want to use books like Confessions of a Shopaholic, but I’m going to do an experiment and see what happens. There will be lots of other reading too. I am certain my students will survive.

When I first read about all this, I got upset, and reading this has helped me pinpoint it. It’s not that I care that Egan doesn’t like “chick lit,” because I don’t either for the most part. And it’s not that she came out and said so, because I think that’s her right. It’s the idea that someone whose writing I love maybe isn’t very nice. I think we like to think that we’d get along with our favorite writers and the truth is that some of them are jerks. Egan may very well not be–she may have just been having an overwhelming day. But it’s still jarring.

Thanks, Roxane. I agree that the term was probably coined by a marketing department, or someone in the industry other than the authors themselves. But what I found to be strange was that none of the authors that fall into the category (or any of its readers) have really questioned it. The Michelle Gorman essay in The Guardian only goes so far as to say that she’s proud of what she does and not offended by the label. But that’s kind of it. Granted, it’d be hard (maybe impossible) to overcome a label that’s pretty deeply ingrained in the marketing aspect of publishing. Why would the publishing houses care if it’s making them a lot of money? But if someone as big as Jennifer Weiner started up the conversation, it’d be interesting to see what kind of effect it would have. It just seems really strange to me that it hasn’t happened thus far.

What I would’ve liked to touch on if I’d had more room was that a lot of what the chick lit demographic defends is subject matter–that the lives of women and what’s often covered in chick lit (careers, love, sisters, mothers and daughters, etc.) is constantly being demeaned. And this is where I think the defensive energy is a little misplaced. Several people have pointed out that Egan’s subject matter often coincides with chick lit subject matter–she writes about supermodels, celebrity, fashion stylists, high-powered PR women. The difference IS that Egan’s doing something with it that’s pretty extraordinary (at least in my opinion.) Great literature isn’t defined by subject matter; it’s the execution, rather. I don’t know if I’ve ever read someone who writes about motherhood and being a housewife better than Grace Paley. Danielle Evans wrote a great collection with many of the stories revolving around teenage girls. There are a lot of women writing well about the lives of women. And it would indeed be outrageous to say that these subject matters are frivolous, which I think is where the argument gets thrown off. If we’re essentially writing about the same things, we’re faced with the bigger question of what’s good and what’s not as good.

Thanks, Roxane. I agree that the term was probably coined by a marketing department, or someone in the industry other than the authors themselves. But what I found to be strange was that none of the authors that fall into the category (or any of its readers) have really questioned it. The Michelle Gorman essay in The Guardian only goes so far as to say that she’s proud of what she does and not offended by the label. But that’s kind of it. Granted, it’d be hard (maybe impossible) to overcome a label that’s pretty deeply ingrained in the marketing aspect of publishing. Why would the publishing houses care if it’s making them a lot of money? But if someone as big as Jennifer Weiner started up the conversation, it’d be interesting to see what kind of effect it would have. It just seems really strange to me that it hasn’t happened thus far.

What I would’ve liked to touch on if I’d had more room was that a lot of what the chick lit demographic defends is subject matter–that the lives of women and what’s often covered in chick lit (careers, love, sisters, mothers and daughters, etc.) is constantly being demeaned. And this is where I think the defensive energy is a little misplaced. Several people have pointed out that Egan’s subject matter often coincides with chick lit subject matter–she writes about supermodels, celebrity, fashion stylists, high-powered PR women. The difference IS that Egan’s doing something with it that’s pretty extraordinary (at least in my opinion.) Great literature isn’t defined by subject matter; it’s the execution, rather. I don’t know if I’ve ever read someone who writes about motherhood and being a housewife better than Grace Paley. Danielle Evans wrote a great collection with many of the stories revolving around teenage girls. There are a lot of women writing well about the lives of women. And it would indeed be outrageous to say that these subject matters are frivolous, which I think is where the argument gets thrown off. If we’re essentially writing about the same things, we’re faced with the bigger question of what’s good and what’s not as good.

Thanks, Roxane. I agree that the term was probably coined by a marketing department, or someone in the industry other than the authors themselves. But what I found to be strange was that none of the authors that fall into the category (or any of its readers) have really questioned it. The Michelle Gorman essay in The Guardian only goes so far as to say that she’s proud of what she does and not offended by the label. But that’s kind of it. Granted, it’d be hard (maybe impossible) to overcome a label that’s pretty deeply ingrained in the marketing aspect of publishing. Why would the publishing houses care if it’s making them a lot of money? But if someone as big as Jennifer Weiner started up the conversation, it’d be interesting to see what kind of effect it would have. It just seems really strange to me that it hasn’t happened thus far.

What I would’ve liked to touch on if I’d had more room was that a lot of what the chick lit demographic defends is subject matter–that the lives of women and what’s often covered in chick lit (careers, love, sisters, mothers and daughters, etc.) is constantly being demeaned. And this is where I think the defensive energy is a little misplaced. Several people have pointed out that Egan’s subject matter often coincides with chick lit subject matter–she writes about supermodels, celebrity, fashion stylists, high-powered PR women. The difference IS that Egan’s doing something with it that’s pretty extraordinary (at least in my opinion.) Great literature isn’t defined by subject matter; it’s the execution, rather. I don’t know if I’ve ever read someone who writes about motherhood and being a housewife better than Grace Paley. Danielle Evans wrote a great collection with many of the stories revolving around teenage girls. There are a lot of women writing well about the lives of women. And it would indeed be outrageous to say that these subject matters are frivolous, which I think is where the argument gets thrown off. If we’re essentially writing about the same things, we’re faced with the bigger question of what’s good and what’s not as good.

Thanks, Roxane. I agree that the term was probably coined by a marketing department, or someone in the industry other than the authors themselves. But what I found to be strange was that none of the authors that fall into the category (or any of its readers) have really questioned it. The Michelle Gorman essay in The Guardian only goes so far as to say that she’s proud of what she does and not offended by the label. But that’s kind of it. Granted, it’d be hard (maybe impossible) to overcome a label that’s pretty deeply ingrained in the marketing aspect of publishing. Why would the publishing houses care if it’s making them a lot of money? But if someone as big as Jennifer Weiner started up the conversation, it’d be interesting to see what kind of effect it would have. It just seems really strange to me that it hasn’t happened thus far.

What I would’ve liked to touch on if I’d had more room was that a lot of what the chick lit demographic defends is subject matter–that the lives of women and what’s often covered in chick lit (careers, love, sisters, mothers and daughters, etc.) is constantly being demeaned. And this is where I think the defensive energy is a little misplaced. Several people have pointed out that Egan’s subject matter often coincides with chick lit subject matter–she writes about supermodels, celebrity, fashion stylists, high-powered PR women. The difference IS that Egan’s doing something with it that’s pretty extraordinary (at least in my opinion.) Great literature isn’t defined by subject matter; it’s the execution, rather. I don’t know if I’ve ever read someone who writes about motherhood and being a housewife better than Grace Paley. Danielle Evans wrote a great collection with many of the stories revolving around teenage girls. There are a lot of women writing well about the lives of women. And it would indeed be outrageous to say that these subject matters are frivolous, which I think is where the argument gets thrown off. If we’re essentially writing about the same things, we’re faced with the bigger question of what’s good and what’s not as good.

Thanks, Roxane. I agree that the term was probably coined by a marketing department, or someone in the industry other than the authors themselves. But what I found to be strange was that none of the authors that fall into the category (or any of its readers) have really questioned it. The Michelle Gorman essay in The Guardian only goes so far as to say that she’s proud of what she does and not offended by the label. But that’s kind of it. Granted, it’d be hard (maybe impossible) to overcome a label that’s pretty deeply ingrained in the marketing aspect of publishing. Why would the publishing houses care if it’s making them a lot of money? But if someone as big as Jennifer Weiner started up the conversation, it’d be interesting to see what kind of effect it would have. It just seems really strange to me that it hasn’t happened thus far.

What I would’ve liked to touch on if I’d had more room was that a lot of what the chick lit demographic defends is subject matter–that the lives of women and what’s often covered in chick lit (careers, love, sisters, mothers and daughters, etc.) is constantly being demeaned. And this is where I think the defensive energy is a little misplaced. Several people have pointed out that Egan’s subject matter often coincides with chick lit subject matter–she writes about supermodels, celebrity, fashion stylists, high-powered PR women. The difference IS that Egan’s doing something with it that’s pretty extraordinary (at least in my opinion.) Great literature isn’t defined by subject matter; it’s the execution, rather. I don’t know if I’ve ever read someone who writes about motherhood and being a housewife better than Grace Paley. Danielle Evans wrote a great collection with many of the stories revolving around teenage girls. There are a lot of women writing well about the lives of women. And it would indeed be outrageous to say that these subject matters are frivolous, which I think is where the argument gets thrown off. If we’re essentially writing about the same things, we’re faced with the bigger question of what’s good and what’s not as good.

Yeah, I can totally see how her comments would be jarring in that context. It didn’t throw me off because I’m not nearly as familiar with Egan as I am with Weiner, et al.

I think back when the term was coined, there may have been more discussion about it. I remember way back when the genre first got that name and there was quite a lot of discussion but then the term stuck and (I’m just guessing here), those writers decided to pick their battles.

I do agree that Egan’s book, and the writing of many other women writers of literary fiction, deal with the exact same themes as chick lit. I’m glad you brought up Evans’s collection because that’s a great example of a book of stories all about the lives of women that is so so great. I would love to see someone talk about that bigger question of what’s good and what isn’t and why.

Books that aren’t great, as opposed to books you don’t like. Because you only like great things.

I don’t understand why the genre can’t be referred to using some variation of “romantic comedy”, which has clearly replaced the more derogatory “chick flick” when it comes to the film counterparts of said books. In addition to being less problematic, it would actually probably be pretty profitable for authors and publishers to make an effort to do this because it 1) ties them to the huge romcom movie industry they are often supplying the stories for 2) does less to deter male readers (and authors) from entering the market and 3) generally sounds like something that is more enjoyable and better describes what the genre is about.

Even as sometimes-reader of “chick lit” (along with it’s YA counterpart “pink lit”, which isn’t any better at all) I’d read the interview and didn’t really think Jennifer Egan’s comments were anything to get upset about at all. And for the record, I haven’t read The Goon Squad, but have read Good in Bed (and quite enjoyed it).

Enjoying both post and comments. What bothered me about Egan’s comment was that it seemed divorced from the actual issue of Kaavya Viswanathan’s plagiarism. Following Egan’s logic, would her plagiarism somehow have been less egregious had Viswanathan lifted from ‘better models’?

Some things never change. “America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash — and should be ashamed of myself if I did succeed.” –Nathaniel Hawthorne to his publisher, 1855.

Yeah, her logic was pretty confusing. The girl in question stole from Salman Rushdie as well as chick lit authors. Maybe Egan’s saying the very celebrated Rushdie sucks? Maybe Rushdie fans should get upset and violent Islamocists should cheer Jennifer Egan. Overall, her comment is not one to get upset about because it doesn’t seem like she really thought too much about what she was saying. Perhaps it was a long day and she was just shooting off her mouth. Or maybe she was trying to make a writerly pronouncement and fell on her face trying. Who cares.

excellent post. the backlash seems to be part of the comment society where a conversation/interview can be published and viewed and it’s so easy for people to respond. Egan said many many many many things that day and I don’t think she dropped this line in there as a calculated move.

“I understand what drives Weiner to discuss these issues and to continue to be outspoken. Jennifer Weiner is actually doing exactly what Jennifer Egan wants young women writers to do, to “shoot high and not cower.” ”

Disagree totally. J. Weiner is NOT aiming high in her art and writing, which is what Egan wants young women writers to do. J. Weiner is aiming high for her bank account and celebrity, but doesn’t want to do the work of actually producing great fiction. In her own interviews, she even says things like she doesn’t try to be a genius writer, she just wants to be a female Nick Hornby. Whoopdie doo.

Perhaps I’m being unfair. Maybe Weiner does strive as hard as she can to write great work and she just isn’t great. That’s fine. But her comments come off as “I want to be rich and critically acclaimed for what I’ve done” not “I want to produce work that is worthy of being critically acclaimed.”

Is that aiming high? Not really. Who doesn’t want to be rich and famous? Everyone wants that, and going on Twitter to claim you want it isn’t aiming high. Trying to produce quality work is aiming high.

I kind of like jerky writers and artists! But I honestly don’t think Egan sounds like a mean person there at all…

I think Egan was objecting to how Viswanathan had been heralded as a prodigy (so young, so talented, so Ivy League, so many projects, so many zeroes) while her artistic ambitions were relatively modest. Whether the finished product was plagiarized or merely derivative is irrelevant to that point.

Just to make sure I’m thinking of the right person, I went and read the start of her last novel on amazon. Weiner is definitely not aiming high in fiction. She is just another person with the attitude they are owed everything without having to work for it.

Rhetorical question: How is Jennifer Weiner different from a Stephen King or a Frank Herbert or an Orson Scott Card or Larry McMurtry or a Dashiell Hammett? It seems to me that Egan’s comment about “banal and derivative” work was about genre or popular fiction. Do male genre writers get more “cred” than female ones?

Well, she is nowhere near as good or innovative as a Hammett or Herbert. The question might be more, how is Jennifer Weiner different from a Dan Brown or perhaps a Michael Connelly?

When you say nowhere near as good, do you mean on the level of sentence, in terms of lyricism, or do you mean subject matter, or perhaps theme?

Which is not to say that the heart of your question isn’t a good one. Is “chick lit” as a genre unfairly looked down upon compared to more “masculine” genres like detective novels are horror novels? I think the answer is probably yes. But even so, we need to find a fair comparison. Hammett is one of the central figures of detective fiction and invented a whole genre of it. Steven King is, for better or worse, the most significant horror writer of the last 50 years and maybe the most important and central genre/popular authors in any genre. Is Weiner the “chick lit” version of any of the people you mentioned? Is she regarded as one of the central or founding figures of the genre? is she known for innovations to the genre and spawning countless imitators? etc.

Well, I probably mean it on almost every level. But mainly I mean it in that I don’t think she is, or is regarded as (correct me if I’m wrong), as central, innovative or important of a figure in her genre as those authors you listed are in their respective genres.

We cross posted though!

Here’s what worries me: Back in 1974, Frederick Busch wrote a mixed NYTBR of an Alice Munro collection. It was one of her early books. He said–in essence–gee, she sure does write about wives a lot! And that was the source of his determination that she must not be very innovative or ambitious. http://www.nytimes.com/1974/10/27/books/munro-something.html I think that Weiner has spawned countless imitators and devotees, and so, just as we have given King and others cred we should ask ourselves what prevents us from giving Weiner a fair read. Or really, ANY book with a feminized book jacket.

Here’s what worries me: Back in 1974, Frederick Busch wrote a mixed NYTBR of an Alice Munro collection. It was one of her early books. He said–in essence–gee, she sure does write about wives a lot! And that was the source of his determination that she must not be very innovative or ambitious. http://www.nytimes.com/1974/10/27/books/munro-something.html I think that Weiner has spawned countless imitators and devotees, and so, just as we have given King and others cred we should ask ourselves what prevents us from giving Weiner a fair read. Or really, ANY book with a feminized book jacket.

I think there is absolutely sexism in the industry and people’s reading habits. I’m sure I’d agree with you and Wiener on a lot of the causes. However, that doesn’t mean that any chick lit writer is the equivalent of any male writer one could bring up, and we have to be careful not to stack the deck too much in either direction when making comparisons. Sorry if I sound pedantic, I just think it is important. Weiner seems like a pretty unnotable writer, even in the limiting genre of “women’s fiction.” At the very least, Weiner is a very contemporary author, publishing her first book in 2001, so it is pretty impossible to compare her to past titans of other genres whose reputations have been solidified and their influence proven. Who is a mediocre writer who has only published books in the last 10 years in horror or crime fiction? We could compare one of those to Weiner.

Weiner is fairly significant in her genre.

“In Her Shoes became a major studio film (and a great one)” is hilarious. I love these satirical posts.

Okay. And, actually, I apologize, because I’ve had a shitty day and I think that has fed into my comment here. I’m sure that your class would be a fine experience. The first thing that turns its head when I’m in a bad mood is a lack of tolerance for things I probably have a prejudice against as being “low-brow”. Whatever. Be well.

I sat, eased a few M&M’s into my mouth, and flipped to page 132, which turned out to be “Good in Bed,” Moxie’s regular male-written feature designed to help the average reader understand what her boyfriend was up to…or wasn’t up to, as the case might be. At first my eyes wouldn’t make sense of the letters. Finally, they unscrambled. “Loving a Larger Woman,” said the headline, “By Bruce Guberman.” Bruce Guberman had been my boyfriend for just over three years, until we’d decided to take a break three months ago. And the Larger Woman, I could only assume, was me.

You know how in scary books a character will say, “I felt my heart stop?” Well, I did. Really. Then I felt it start to pound again, in my wrists, my throat, my fingertips. The hair at the back of my neck stood up. My hands felt icy. I could hear the blood roaring in my ears, as I read the first line of the article: “I’ll never forget the day I found out my girlfriend weighed more than I did.”

Samantha’s voice sounded like it was coming from far, far away. “Cannie? Cannie, are you there?”

“I’ll kill him!” I choked.

“Take deep breaths,” Samantha counseled. “In through the nose, out through the mouth.”

Betsy, my editor, cast a puzzled look across the partition that separated our desks. “Are you all right?” she mouthed. I squeezed my eyes shut. My headset had somehow landed on the carpet. “Breathe!” I could hear Samantha say, her voice a tinny echo from the floor. I was wheezing, gasping. I could feel chocolate and bits of candy shell on my teeth. I could see the quote they’d lifted, in bold-faced pink letters that screamed out from the center of the page. “Loving a larger woman,” Bruce had written, “is an act of courage in our world.”

“I can’t believe this! I can’t believe he did this! I’ll kill him!”

I understand the criticism. I DO feel like, however, that I’ve read enough to be able to make a judgment call sometimes. I’m sure I miss out on the odd potential greatness, but I really, literally, do not have time to read everything, and if it doesn’t grab ahold of me at least almost immediately I will probably put it down. UNLESS there is something in it so adverse to my consciousness that I NEED to understand it… I’ve read most of everything Sartre ever wrote. I strongly dislike Sartre, though I can’t help but concede some things to him…

A corner-cutting, ‘solutions’-oriented it’s-all-gonna-be-okay machine.

– but I liked the (impossibly concise) lesson where the Diaz character is led to explicate One Art and suddenly realizes that human life itself can be disclosed by reading silly chick-lit poem thingies carefully.

I guess one could see using Bishop’s poem to engineer a metafictive unpacking of the movie itself as satirically ambitious.

i want my comment to be by steve-o’s and deader’s

so i’ll reply to Darconville

in truth i have read almost none of the post/thread

(steve-o , i read your ‘comment’, that was painful ! )

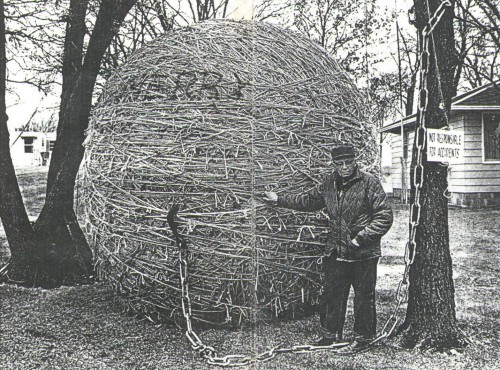

i just wanted to say ‘i like that picture of the big ball of ? ? rope ? twine ? ‘

” so i’ll reply to Darconville ”

or not . . .

I totally agree with this. And I think Weiner was truly pissed because Franzen achieved both critical and commercial success. Her point was that he achieved the critical part because he’s a man. Nope, he achieved it because he actually aims high in his art. Wiener aims at our pocketbooks and that’s why she doesn’t have the critical acclaim she so badly wants. Tom Clancy could complain about the same thing. James Patterson. A million male writers. Chick lit is no different than Washington spy genre books. it’s written with an eye toward the large audience that will purchase it. No one would hesitate to poop on Clancy’s books as not-so-serious. So why give women’s not-so-serious books a pass? I think what Egan said is right on. She and many other fine women writers are aiming high and doing something truly new. So she’s a better than Weiner if you want to be taken seriously as an artist.

The argument about women writing low stakes fiction is tedious to me mostly because many lauded books have been written by men on the same subjects. Even more than men, though, it’s women who should be frustrated (as Ms. Egan is) with the self-perpetuating, perpetually middling culture built up around fiction written by or for ‘women’, the shady demographic of a little over half the planet. It’s not that there shouldn’t be shitty fiction for women–by all means, let there be shit as needed, where need. But while the ultimate argument is always that the shit needs to be rounded out with whatever sort of literature you think most counterweights shit, and the basic worry that this isn’t happening, on a simpler level it rhetorically and logistically breaks down to the same conflict of enfranchisement caught in the Spike Lee/Tyler Perry coin. The concerns of Ms. Egan seem mostly to come from the way intellectually disenfranchised cultures perpetuate their own disenfranchisement even after some of the primary impediments are removed. Spike is concerned, when he examines images he thinks of as ‘coonery buffoonery’ in things by Tyler Perry or others, that in the face of liberating potential these things smack of mere complacency–given the chance to change, will we? Do you call it enfranchisement when the same cultural limitations exerted on you by oppression are self-enforced by the way you choose of your own free will to conduct yourself? These are legitimate questions for any field, really, and I can’t imagine Jennifer Egan having any less right to ask them than Spike–though the responses to each were similarly affronted. At the end of the day you have to decide whether you think they’re accurate or reactionary in assessing the state of things, and whether the response is properly indignant or evidence of cultural insecurity.

[…] published yesterday in HTMLGIANT that essentially (and much more thoroughly and kindly) expresses what I felt after reading Drewis’s piece. Because here’s a thing: my two younger sisters and I can count among us Jodi Picoult, Helen […]

Why should Egan even be expected to be nice? I think this is a gendered expectation to have from a writer. And why does giving an honest opinion that a book is derivative take away from her perceived level of niceness? Nice people can certainly have critical opinions.

Oh wow, I wasn’t actually expecting you to have some sort of belief in objective greatness. Weird.

Objective and subjective are two of the most misused and misunderstood terms.

I am impressed you not only finished the movie but admitted so here and remember quite a bit the poem by EE Cummings – (that’s what she said)

Greg: Look — do you want fame and fortune, or do you want integrity and respect?

Andy: Both.

Trey: Right. Well, there are only a few people in the world who have both those things. And you will never be one of them. What do you want?

[long pause]

Andy: Rich and famous. And on the telly.

Greg: Look — do you want fame and fortune, or do you want integrity and respect?

Andy: Both.

Trey: Right. Well, there are only a few people in the world who have both those things. And you will never be one of them. What do you want?

[long pause]

Andy: Rich and famous. And on the telly.

Amen. The fact that Wiener can’t tell the difference, as a reader, between the two levels under discussion, has a lot to do with why she doesn’t (couldn’t?) write at the higher of the two levels. But, then, I can’t tell the difference between my (quotidian) German and Elfriede Jelinek’s… (actually, I can; having a weaker second language is a valuable resource for anyone who writes in her/his first)

[…] should really read Roxane Gay’s thoughts on Jennifer Egan, “chick lit,” and […]

http://xrl.us/bh8tjk

Yes, it would have been less egregious.

Saying that Weiner’s increasingly regular complaining is somehow following Egan’s advice to “shoot high and not cower” is disingenuous to say the least. Egan was talking about writing and making a specific distinction – i.e not shooting low. If ripping into other people’s opinions (fine by me) and whining (less so) count as shooting high then we live in an extremely ambitious society/world.

I see your point that I shouldn’t expect writers to be nice, but I do expect that of both males and females. If someone had asked her what she thought of the other books, I don’t think I would have felt entirely the same way. But she brought it into the conversation. I don’t think bringing someone up in a public forum to say that their work is banal and derivative is nice. Or effective in making a point, as I think this has unfortunately detracted from her ultimate one.

http://xrl.us/bh8tjk

On the contrary, I don’t believe objectivity exists at all. All I have is my subjective judgment and intuition. If it tells me Thomas Mann is better than Jennifer Weiner, then he is. My subjective existence is the only one I could ever possibly know. Only God could be objective, objectivity doesn’t enter into my process because it doesn’t exist as a concept.

Saying “IMO” is redundant. Anything I utter or think is “IMO”. That should be a given to anyone observing my utterances.

This is not fascistic. You are free to have your own reality if it doesn’t harm anyone.

I also want to say that I mean utterances, not actions. The reason I retracted my initial statement is that it may have crossed a line from mere utterance to negative action, because it may have been construed as being personal.

You know what pisses me off most about Egan’s response? The fact she says “What I want to see is young, ambitious writers.”

Young. Really? Why do they have to be young?

You know what I want to see? (Not that anyone gives a fuck what I want to see) – Good words. I don’t care who writes them, though I sure am glad when women breakthrough and get recognition.

[…] Egan commented on the reaction to her comments during a WSJ interview where she implied that certain books were “derivative, […]

[…] Egan commented on the reaction to her comments during a WSJ interview where she implied that certain books were […]

[…] lit,” versus other fiction genres is a recurring one. Earlier this year, Jennifer Weiner bristled when Jennifer Egan indirectly made some less than charitable comments about the genre. Last year, […]