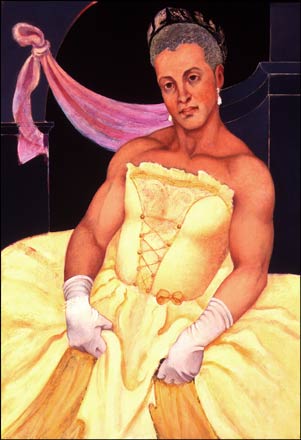

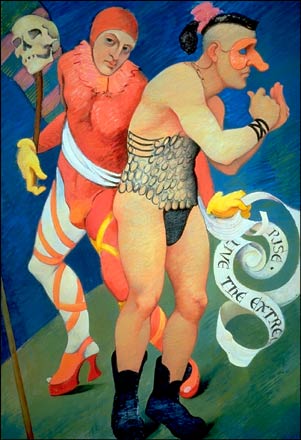

SCUMBAG HYPOCRITE ALERT: Maureen Mullarkey loves painting the Gay Pride Parade, but she hates everything it stands for, and all the people in it–and probably you as well

Maureen Mullarkey, the art critic and artist well-known to the gay community for her iconic portraits of drag queens and gay pride parades, was yesterday revealed by the NY Daily News to have contributed $1000 to Proposition 8. […] When asked how she could have donated money to fight gay marriage after making money from her depictions of gays, she just said, “So? If you write that story, I’ll sue you.”

(h/t to Joe.My.God)

A quick trip over to Campaignmoney.com reveals that the person in questions–Mrs. Maureen Mullarkey of Chappaqua, NY–ALSO gave nearly $1000 to different arms of McCain/Palin ’08.

On her website, in an interview, Maureen explains that she likes the Gay Pride parade as a source of imagery because “it is marvelous spectacle. There is so much to look at.” But wouldn’t any old parade provide that kind of imagery, the interviewer asks? “Not for me,” says Maureen. “I’ve never really liked parades much. How many marching bands can you take before your eyes glaze over? But when the majorette is a middle-aged man in a tutu and sneakers you know you are not in Kansas and you might want to stay awake.”

Then she goes off on a whole thing about why she uses Medeival motifs and how the Gay Pride Parade proves that Dionysus is still “alive, powerful, and under our own porch. This is the great moral lesson of the parade.”

Yes, you read that right. For Mullarkey, the point of a Gay Pride Parade is not that gays are real people with real rights and a legitimate claim to assert their individual and collective self-hood in the public sphere. The point is that gays remind us how topsy-turvy this old world can be, which presumably is why Mullarkey feels so comfortable–perhaps even obligated–to go around EXPLOITING THE BLAZING SHIT OF PEOPLE SHE SECRETLY HATES AND TO WHOM SHE HOPES TO DENY THE BASIC RIGHTS OF CITIZENSHIP. Sort of like a plantation owner sitting on his porch just really and truly impessed by the hijinks at a darkie wedding. Long as none of them come too near the big house, and long as they’re all back in the field by sun-up, everything’s gonna be just fine.

Dear Maureen: Hope Chappaqua’s lovely right now, because methinks you won’t be taking the MetroNorth down Manhattan-way for a good long while. Better up your Netflix.

Tags: gay pride, Maureen Mullarkey, proposition 8

This is one of those things where you can read a lot into it- she’s a bad person, she’s confused, she’s out of her mind, and all of that might be true- but the simplest thing is she is a fucking idiot. Really. Just a garden variety idiot.

Hmm. Thing number one. I don’t think prop 8 equals gay hatred. Thing number two. Regardless of a person’s belief construct, I believe they have the right to make art out of anything they want and for whatever reason they want.

Hmm. Thing number one. I don’t think prop 8 equals gay hatred. Thing number two. Regardless of a person’s belief construct, I believe they have the right to make art out of anything they want and for whatever reason they want.

gotta go with darby on this one. beliefs are beliefs. art is art.

not that i particularly think her work is worth a shit. or her either for that matter. but still.

gotta go with darby on this one. beliefs are beliefs. art is art.

not that i particularly think her work is worth a shit. or her either for that matter. but still.

Yeah, I agree with darby also. Though I can’t see how this would help her, seeing as some of the people who buy her art are probably gay? Were probably gay, I guess. It is a pretty scummy thing to do, but I think the plantation owner imagery is probably a little overblown… she’s not actively persecuting them. If only the only way plantation owners profited off of black people was painting kind of amusing paintings of them.

Yeah, I agree with darby also. Though I can’t see how this would help her, seeing as some of the people who buy her art are probably gay? Were probably gay, I guess. It is a pretty scummy thing to do, but I think the plantation owner imagery is probably a little overblown… she’s not actively persecuting them. If only the only way plantation owners profited off of black people was painting kind of amusing paintings of them.

Yes, Darby, she has the right to do everything she did. And I have the right to connect the dots between what appears to me to be an irresolvable conflict between two aspects of her behavior. I just connected a dot– or rather, re-blogged a dot-connection somebody else was smart enough to make.

About the second charge, that being against prop 8 equals gay hatred- I’m sorry, but in this case I think it does. It’s one thing to argue with the specifics of a given bill–as some have done–and it’s one thing to argue that measures like Prop 8 don’t go far enough, because what we really need is to dis-entangle the entire notion of a two-person marriage from the prospect of having rights like health care, hospital visitation, etc. See any number of Richard Kim’s writings on The Nation’s website about this, and/or the special “marriage issue” of the magazine he co-edited.

But what Mullarkey has done, it seems to me, is something else altogether- it’s of an extraordinarily high order of hypocrisy, and it absolutely DOES express a form of hatred–whether or not she cops to it, or even knows it. When you pour money into a fund to defeat a ballot measure in A STATE YOU DON’T LIVE IN, because you’re concerned that the passage of equal-rights legislation in that state may set a precedent for similar legislation and recognition of rights in other states around the country (and, after all, wasn’t that the big conservative fear about Prop 8- that California tends to lead the rest of the country on these kinds of issues) then clearly, there can really be no question that you oppose the recognition of those people’s rights. And the active attempt to stop the recognition of a basic human right, the willingness to perpetuate a system of denial of full citizenship to people who are citizens, is a form of hatred. Plain and simple. It’s discriminatory, it’s wrong, and it’s fucking ugly. Considered in this light, I fail to see how Mullarkey’s paintings can be considering anything other than a form of exploitation.

Also, not that at no time did I use the word “grant” or “give” in relation to rights. Human rights are inalienable, which means it is not the province of government to decide who gets them or when or for how long, but only to uphold them. An inalienable human right is a bigger thing than any government, and our country was founded on the principle that one way the government **proves to the citizenry its legitimacy to govern** is by seeing that those rights are upheld. They can’t be taken away, only denied or refused recognition.

In pure philosophical terms, I’m of the Richard Kim (et al.) school of thought inasmuch as I don’t see what my desire to have sex with the same person over and over again forever (or our mutual desire to fuck every 3rd party we two can get our hands on for that matter, if that’s the way we feel about it) could possibly have to do with my ability to have health care, which btw I also feel is a basic human right., or the way my taxes are filed, or etc etc etc.

But in a world where pure philosophy is not an option–and speaking as a straight, uninsured single man with no dependents, who doesn’t really have a lot to personally lose or gain from Prop 8 or any other measure like it–I’ll take what I can get. In a culture which still continues to privilege the 1-on-1 marriage over and at the exclusion of any and all forms of social, economic and matrimonial union other than itself, then it follows that we must ensure that that institution is opened as widely as possible. That’s all.

Yes, Darby, she has the right to do everything she did. And I have the right to connect the dots between what appears to me to be an irresolvable conflict between two aspects of her behavior. I just connected a dot– or rather, re-blogged a dot-connection somebody else was smart enough to make.

About the second charge, that being against prop 8 equals gay hatred- I’m sorry, but in this case I think it does. It’s one thing to argue with the specifics of a given bill–as some have done–and it’s one thing to argue that measures like Prop 8 don’t go far enough, because what we really need is to dis-entangle the entire notion of a two-person marriage from the prospect of having rights like health care, hospital visitation, etc. See any number of Richard Kim’s writings on The Nation’s website about this, and/or the special “marriage issue” of the magazine he co-edited.

But what Mullarkey has done, it seems to me, is something else altogether- it’s of an extraordinarily high order of hypocrisy, and it absolutely DOES express a form of hatred–whether or not she cops to it, or even knows it. When you pour money into a fund to defeat a ballot measure in A STATE YOU DON’T LIVE IN, because you’re concerned that the passage of equal-rights legislation in that state may set a precedent for similar legislation and recognition of rights in other states around the country (and, after all, wasn’t that the big conservative fear about Prop 8- that California tends to lead the rest of the country on these kinds of issues) then clearly, there can really be no question that you oppose the recognition of those people’s rights. And the active attempt to stop the recognition of a basic human right, the willingness to perpetuate a system of denial of full citizenship to people who are citizens, is a form of hatred. Plain and simple. It’s discriminatory, it’s wrong, and it’s fucking ugly. Considered in this light, I fail to see how Mullarkey’s paintings can be considering anything other than a form of exploitation.

Also, not that at no time did I use the word “grant” or “give” in relation to rights. Human rights are inalienable, which means it is not the province of government to decide who gets them or when or for how long, but only to uphold them. An inalienable human right is a bigger thing than any government, and our country was founded on the principle that one way the government **proves to the citizenry its legitimacy to govern** is by seeing that those rights are upheld. They can’t be taken away, only denied or refused recognition.

In pure philosophical terms, I’m of the Richard Kim (et al.) school of thought inasmuch as I don’t see what my desire to have sex with the same person over and over again forever (or our mutual desire to fuck every 3rd party we two can get our hands on for that matter, if that’s the way we feel about it) could possibly have to do with my ability to have health care, which btw I also feel is a basic human right., or the way my taxes are filed, or etc etc etc.

But in a world where pure philosophy is not an option–and speaking as a straight, uninsured single man with no dependents, who doesn’t really have a lot to personally lose or gain from Prop 8 or any other measure like it–I’ll take what I can get. In a culture which still continues to privilege the 1-on-1 marriage over and at the exclusion of any and all forms of social, economic and matrimonial union other than itself, then it follows that we must ensure that that institution is opened as widely as possible. That’s all.

Sorry guys, but you’re all wrong on this one. the plantation analogy is extreme- but difference of degree is not the same as difference of kind. Prop 8 is part of a de-segregation movement. And that’s not an analogy at all.

Sorry guys, but you’re all wrong on this one. the plantation analogy is extreme- but difference of degree is not the same as difference of kind. Prop 8 is part of a de-segregation movement. And that’s not an analogy at all.

Yeh, I think this woman is a cunt for giving money to Prop 8. But her art is fucking cheesy anyway so who cares about this cunt. I always love seeing people who are full of shit get dragged out into the light, so, thanks Justin. And though I think gays should be able to get married if they want to, I don’t ever want to get married. That’s why I’m fucking gay. Or something along those lines. I don’t know. It’s hard to explain.

Yeh, I think this woman is a cunt for giving money to Prop 8. But her art is fucking cheesy anyway so who cares about this cunt. I always love seeing people who are full of shit get dragged out into the light, so, thanks Justin. And though I think gays should be able to get married if they want to, I don’t ever want to get married. That’s why I’m fucking gay. Or something along those lines. I don’t know. It’s hard to explain.

it doesn’t change the image she painted on the paper.

it doesn’t change the image she painted on the paper.

shit, if anything it makes it more interesting. they’re pretty boring to look at on their own.

shit, if anything it makes it more interesting. they’re pretty boring to look at on their own.

i mean, if she was trying to get in a taxi with me, i’d probably fart in her mouth. but to lambast her as an artist because she’s a bigot, that’s just as lame, i think.

i mean, if she was trying to get in a taxi with me, i’d probably fart in her mouth. but to lambast her as an artist because she’s a bigot, that’s just as lame, i think.

* appears to be a bigot *

* appears to be a bigot *

doesn’t take common sense to see the world. which is what a good artist does. takes a lot of common sense to figure the world out, though. that’s where she fails.

doesn’t take common sense to see the world. which is what a good artist does. takes a lot of common sense to figure the world out, though. that’s where she fails.

Gian- check out Richard’s essay “The Descent of Marriage?” It’s short and it speaks directly to your heart. One of these days I’ll do a whole post just devoted to him.

http://www.thenation.com/doc/20040315/kim

Blake- I really disagree with you here. It’s impossible to consider Pound without taking into account his embrace of fascism, which it must be admitted was based on virulent anti-Semitism. That doesn’t negate Pound’s value, but it’s a necessary complicating factor.

And it has everything to do with the nature of the work. T.S. Eliot was a pretty virulent anti-Semite himself, but saving the few places where it overtly rears its head (“Burbank with a Baedeker…” for example, and the couple other well-known examples) you’d have to go out of your way to bring it into a general discussion of Eliot. You could write a book about the Four Quartets, for example, and never once bring it up. With Pound, you don’t have that luxury, because his politics is part of the manifest content of his work- in the Cantos, in “Jefferson and/or Mussolini,” and in the fact that he spent part of his life working with the Italian fascist government and nearly got convicted of treason for it, then wound up in a mental hospital instead.

Lovecraft is another one- you can ‘read’ a loathed figuration of the feminine into his monsters if you want to, or you can limit yourself to what’s on the page. What you can’t avert your eyes from is his wild hatred of blacks, Jews, and immigrants in general. For a story like “The Horror at Red Hook,” it’s literally the point of the entire work, not even just a constitutive element.

with Mullarkey here, there seems to be no question in my mind that the decision to paint the Gay Pride Parade specifically (“Why not just any parade?” asks the interviewer–“oh it couldn’t be just *any* parade” replies Mrs. M) infuses the work with manifest political content–or at least tries to get you to think so. She’s smart to re-direct the attention to the Medeivalist aspect of the work, because that’s ALSO part of the manifest content, and probably the single best thing the work has going for it. So she talks up Point B as if it were Point A, and relies on you the viewer to supply the politics, the ostensible Real Point A, even though what she’s left off the page is that her politics are the inverse of what her work would otherwise suggest that they are. Hence- hypocrisy. And re what Andre said before- taking a gay person’s money for any of these paintings, and then using that money to support a ballot measure intended to deny a basic human right to the same person you just profited off of, just seems to me to be so debased and low, words just fail me.

Gian- check out Richard’s essay “The Descent of Marriage?” It’s short and it speaks directly to your heart. One of these days I’ll do a whole post just devoted to him.

http://www.thenation.com/doc/20040315/kim

Blake- I really disagree with you here. It’s impossible to consider Pound without taking into account his embrace of fascism, which it must be admitted was based on virulent anti-Semitism. That doesn’t negate Pound’s value, but it’s a necessary complicating factor.

And it has everything to do with the nature of the work. T.S. Eliot was a pretty virulent anti-Semite himself, but saving the few places where it overtly rears its head (“Burbank with a Baedeker…” for example, and the couple other well-known examples) you’d have to go out of your way to bring it into a general discussion of Eliot. You could write a book about the Four Quartets, for example, and never once bring it up. With Pound, you don’t have that luxury, because his politics is part of the manifest content of his work- in the Cantos, in “Jefferson and/or Mussolini,” and in the fact that he spent part of his life working with the Italian fascist government and nearly got convicted of treason for it, then wound up in a mental hospital instead.

Lovecraft is another one- you can ‘read’ a loathed figuration of the feminine into his monsters if you want to, or you can limit yourself to what’s on the page. What you can’t avert your eyes from is his wild hatred of blacks, Jews, and immigrants in general. For a story like “The Horror at Red Hook,” it’s literally the point of the entire work, not even just a constitutive element.

with Mullarkey here, there seems to be no question in my mind that the decision to paint the Gay Pride Parade specifically (“Why not just any parade?” asks the interviewer–“oh it couldn’t be just *any* parade” replies Mrs. M) infuses the work with manifest political content–or at least tries to get you to think so. She’s smart to re-direct the attention to the Medeivalist aspect of the work, because that’s ALSO part of the manifest content, and probably the single best thing the work has going for it. So she talks up Point B as if it were Point A, and relies on you the viewer to supply the politics, the ostensible Real Point A, even though what she’s left off the page is that her politics are the inverse of what her work would otherwise suggest that they are. Hence- hypocrisy. And re what Andre said before- taking a gay person’s money for any of these paintings, and then using that money to support a ballot measure intended to deny a basic human right to the same person you just profited off of, just seems to me to be so debased and low, words just fail me.

but the question is: what is wrong with complication?

why does pound get by over anybody else?

gian probably has the best point: her art is shitty, so who cares to defend her?

i don’t know. i am against political entailing. i wish i really liked her stuff so i could argue for her. but she might as well get shit on in a rubber suit.

i may have beaten this drum hard on this site, but i am sticking with the ‘nothing is true, everything is permitted’ mantra

but the question is: what is wrong with complication?

why does pound get by over anybody else?

gian probably has the best point: her art is shitty, so who cares to defend her?

i don’t know. i am against political entailing. i wish i really liked her stuff so i could argue for her. but she might as well get shit on in a rubber suit.

i may have beaten this drum hard on this site, but i am sticking with the ‘nothing is true, everything is permitted’ mantra

accept everyone

accept everyone

I’m not arguing with that mantra, in the sense that she has the absolute right to live her life how she wants, contradictions and all. I just don’t see how her right to do that pre-empts my right to call her on her bullshit. It would seem that the two go hand in hand.

Pound doesn’t get a free pass at all! That’s what I’m saying. It’s not OK to deny him his significance because his politics were odious, but neither is it OK to deny the odiousness of his politics because he is significant. It’s a warts-and-all approach, and when the art and the life are so thoroughly conflated, it’s just being a good reader to understand how all these things intertwine.

How did Gary Lutz vote in the last election? Does he prefer Jefferson to Hamilton? You don’t know, and when you say it doesn’t matter, you’re right, because Gary’s work is a-political (unless you consider the vivid depiction of morphic, non-hetero-normative sexuality inherently political, which I sort of do, but not in a limiting way) and so unless you’re in a lit theory class and writing an essay on the topic I outlined in the parenthetical, then who cares?

But when Brian Evenson writes a book like Father of Lies, and that book is rightly understood as a critical engagement with the faith he was raised in and the politics of that faith’s crony class of elders, you’re engaging in the same basic process as I am with Mullarkey here:

1) What is the artist’s relationship to the subject?

2) What position of experience/interest is the artist speaking from?

3) Why did this artist adopt this stance on this subject, and what does s/he hope to gain/show by so doing?

These aren’t unreasonable questions to ask ourselves. To me, Mullarkey’s portraits–in the light of her politics–seem to infantalize and sentimentalize her subjects. That’s a problem for me, and no different than any other example of bigotry I’ve pointed out above. Would I feel the same way about the work if I didn’t have this story providing the framework for my viewing it? We’ll never know, since in this case both came to my attention at the same time.

I’m not arguing with that mantra, in the sense that she has the absolute right to live her life how she wants, contradictions and all. I just don’t see how her right to do that pre-empts my right to call her on her bullshit. It would seem that the two go hand in hand.

Pound doesn’t get a free pass at all! That’s what I’m saying. It’s not OK to deny him his significance because his politics were odious, but neither is it OK to deny the odiousness of his politics because he is significant. It’s a warts-and-all approach, and when the art and the life are so thoroughly conflated, it’s just being a good reader to understand how all these things intertwine.

How did Gary Lutz vote in the last election? Does he prefer Jefferson to Hamilton? You don’t know, and when you say it doesn’t matter, you’re right, because Gary’s work is a-political (unless you consider the vivid depiction of morphic, non-hetero-normative sexuality inherently political, which I sort of do, but not in a limiting way) and so unless you’re in a lit theory class and writing an essay on the topic I outlined in the parenthetical, then who cares?

But when Brian Evenson writes a book like Father of Lies, and that book is rightly understood as a critical engagement with the faith he was raised in and the politics of that faith’s crony class of elders, you’re engaging in the same basic process as I am with Mullarkey here:

1) What is the artist’s relationship to the subject?

2) What position of experience/interest is the artist speaking from?

3) Why did this artist adopt this stance on this subject, and what does s/he hope to gain/show by so doing?

These aren’t unreasonable questions to ask ourselves. To me, Mullarkey’s portraits–in the light of her politics–seem to infantalize and sentimentalize her subjects. That’s a problem for me, and no different than any other example of bigotry I’ve pointed out above. Would I feel the same way about the work if I didn’t have this story providing the framework for my viewing it? We’ll never know, since in this case both came to my attention at the same time.

somebody kill me if I ever start asking those three questions about the art I experience.

You keep assuming art is, unless obviously not, politically charged, and I can’t stand that as a default. Even if it is, I never, as a reader, consider it. Art is art, who cares about the intention of the artist and whether it coincides with the experience of the reader.

I keep thinking of Mullarkey as someone who sees gay pride parades and thinks there’s something interesting about them and maybe a little beautiful so she paints pictures of them and that’s it. It’s hard for me to imagine she has a sinister or political intent. Why can’t her political views and her art be separate?

A de-segregation movement? Shouldn’t it be the other way around? A re-segregation movement?

Anyway, I don’t agree with Prop-8 at all… I just don’t think contributing money to legitimate political campaigns (whether you believe they are or not) constitutes “hate”. I could be wrong on that, though. There are so many ways I can be wrong on that. I think all of the rights of marriage should be bestowed on everyone, if they should want them, and let religions, or even individual churches, decide whether or not they want to be “complicit”.

Her art really does get more interesting, though.

somebody kill me if I ever start asking those three questions about the art I experience.

You keep assuming art is, unless obviously not, politically charged, and I can’t stand that as a default. Even if it is, I never, as a reader, consider it. Art is art, who cares about the intention of the artist and whether it coincides with the experience of the reader.

I keep thinking of Mullarkey as someone who sees gay pride parades and thinks there’s something interesting about them and maybe a little beautiful so she paints pictures of them and that’s it. It’s hard for me to imagine she has a sinister or political intent. Why can’t her political views and her art be separate?

A de-segregation movement? Shouldn’t it be the other way around? A re-segregation movement?

Anyway, I don’t agree with Prop-8 at all… I just don’t think contributing money to legitimate political campaigns (whether you believe they are or not) constitutes “hate”. I could be wrong on that, though. There are so many ways I can be wrong on that. I think all of the rights of marriage should be bestowed on everyone, if they should want them, and let religions, or even individual churches, decide whether or not they want to be “complicit”.

Her art really does get more interesting, though.

i actually think her seemingly faux-stance against the subject is the only potentially interesting thing about the pictures. otherwise they are just boring paintings. is she a good person? i dont know. but in this case, for me, context is the only thing making the art interesting.

i actually think her seemingly faux-stance against the subject is the only potentially interesting thing about the pictures. otherwise they are just boring paintings. is she a good person? i dont know. but in this case, for me, context is the only thing making the art interesting.

Separation between art and politics segues into that I can see prop 8 as being something other than gay hatred which you can’t seem to.

Separation between art and politics segues into that I can see prop 8 as being something other than gay hatred which you can’t seem to.

I shouldn’t have commented on this post. Now I’m going to be pissed off all day. Why do you post these kinds of things here, Justin? I think because you write so strongly and CAPITALIZINGLY against something, the only thing to do is argue on its behalf for the sake of the chance that something might be being falsely accused.

I will comment less in the future. Thanks.

Ultimately, I am with you, I voted no on 8. It just wasn’t an obvious no for me.

I shouldn’t have commented on this post. Now I’m going to be pissed off all day. Why do you post these kinds of things here, Justin? I think because you write so strongly and CAPITALIZINGLY against something, the only thing to do is argue on its behalf for the sake of the chance that something might be being falsely accused.

I will comment less in the future. Thanks.

Ultimately, I am with you, I voted no on 8. It just wasn’t an obvious no for me.

Darby- don’t comment less! Rigorous debate is always healthy, maybe most of all when it’s between agreeing parties. Feel free to defend things just because I’m against them anytime you want. To answer your question though, I post them because I feel like it- our little lit world doesn’t exist in a vacuum and I make up as I go along what else seems relevant or interesting enough to bring in from outside that world.

And I’m NOT saying that all art needs to be read politically, or that all art must be political first and foremost, or political at all. But I do think that some art is inherently political, some by intention and some by context, and that anything can be read/critiqued in political terms if the critic so chooses. I’m not saying I’d do that all the time, but I went for it here. In that specific context, I stand by my admittedly just-dashed-off-on-a-whim list of questions, because they offer points of entry into a consideration of this particular nature.

Blake- I totally agree with you. The weird juxtaposition and apparent irreconcilability of the art she made, the art-world she made it for, and whatever her own personal convictions actually are, is absolutely the most interesting thing about this work. It makes a fascinating case study, and jumping-off point for discussion. I’m all for that too.

Darby- don’t comment less! Rigorous debate is always healthy, maybe most of all when it’s between agreeing parties. Feel free to defend things just because I’m against them anytime you want. To answer your question though, I post them because I feel like it- our little lit world doesn’t exist in a vacuum and I make up as I go along what else seems relevant or interesting enough to bring in from outside that world.

And I’m NOT saying that all art needs to be read politically, or that all art must be political first and foremost, or political at all. But I do think that some art is inherently political, some by intention and some by context, and that anything can be read/critiqued in political terms if the critic so chooses. I’m not saying I’d do that all the time, but I went for it here. In that specific context, I stand by my admittedly just-dashed-off-on-a-whim list of questions, because they offer points of entry into a consideration of this particular nature.

Blake- I totally agree with you. The weird juxtaposition and apparent irreconcilability of the art she made, the art-world she made it for, and whatever her own personal convictions actually are, is absolutely the most interesting thing about this work. It makes a fascinating case study, and jumping-off point for discussion. I’m all for that too.

the prop 8 supporter blacklist is facist, not the supporters of prop 8.

i’m politically/philosophically against prop 8, so this isn’t about me, or my sentiments.

the whole point (ostensibly) of a democracy is dissent. Liberals think diversity is yoga class and thai food. what would actually be ‘diverse’ would be to tolerate ideologies/cultures in conflict with one’s own. all this talk about being open-mined, and liberals can’t deal with the fact that some religious person might think differently than them.

i may get heat for this, but i don’t care. living in SF i see this shit all over the place. the bay area is one of the most politically intolerant places i know.

and no, i don’t sympathize with the right either — they’re just as absurd. sam pink’s ‘accept everyone’ is either cliche or profound.

people suck.

the prop 8 supporter blacklist is facist, not the supporters of prop 8.

i’m politically/philosophically against prop 8, so this isn’t about me, or my sentiments.

the whole point (ostensibly) of a democracy is dissent. Liberals think diversity is yoga class and thai food. what would actually be ‘diverse’ would be to tolerate ideologies/cultures in conflict with one’s own. all this talk about being open-mined, and liberals can’t deal with the fact that some religious person might think differently than them.

i may get heat for this, but i don’t care. living in SF i see this shit all over the place. the bay area is one of the most politically intolerant places i know.

and no, i don’t sympathize with the right either — they’re just as absurd. sam pink’s ‘accept everyone’ is either cliche or profound.

people suck.

Yeah, I’m sort of with Jimmy there.

Here are my thoughts on gay marriage. One. I am married and if the definition of my marriage is going to now be changed by the government to something other than what it was when I got married (I know 8 is overturning an existing right, but what I’m arguing is actually whether the right should have gone in in the first place), I am not being given the chance to travel back in time to weigh this new definition on my decision to get married in the first place.

Two. I don’t think allowing gay people to be married under the current concept of ‘marriage’ in our society is how the gay community should be pursuing equal rights. Why, in order to prove love or get tax benefits, does a gay person have to take part in an archaic ceremony based in a religion that doesn’t accept them? What I’d rather see happen is some new union grow and compete with marriage, something not religious and that allows gay/straight/whatever to participate, where state benefits are distributed, something where church and state are separated. I’d like to see this union become more desirable to participate in than marriage, and then let marriage die on its own because its negative aspects will have been exploited. Changing marriage to allow gays doesn’t help this effort, in fact it only hinders it. The problem is that there is no effort, or only very minimal, because liberals can’t get the idea out of their heads that the reason there is opposition to changing marriage is because a vast right wing conspiracy has decided to treat gays unequally. The only thing allowing gays to marry will do for the gay rights movement will be to further the never-ending changing of the law back and forth that gays can marry, gays can’t marry, gays can marry, ad infinitum. In order for a new, better, union to compete with marriage effectively, the definition of marriage should stay the same as how it exists in the minds of all married people alive today, an old-fashioned and stubborn tradition.

Yeah, I’m sort of with Jimmy there.

Here are my thoughts on gay marriage. One. I am married and if the definition of my marriage is going to now be changed by the government to something other than what it was when I got married (I know 8 is overturning an existing right, but what I’m arguing is actually whether the right should have gone in in the first place), I am not being given the chance to travel back in time to weigh this new definition on my decision to get married in the first place.

Two. I don’t think allowing gay people to be married under the current concept of ‘marriage’ in our society is how the gay community should be pursuing equal rights. Why, in order to prove love or get tax benefits, does a gay person have to take part in an archaic ceremony based in a religion that doesn’t accept them? What I’d rather see happen is some new union grow and compete with marriage, something not religious and that allows gay/straight/whatever to participate, where state benefits are distributed, something where church and state are separated. I’d like to see this union become more desirable to participate in than marriage, and then let marriage die on its own because its negative aspects will have been exploited. Changing marriage to allow gays doesn’t help this effort, in fact it only hinders it. The problem is that there is no effort, or only very minimal, because liberals can’t get the idea out of their heads that the reason there is opposition to changing marriage is because a vast right wing conspiracy has decided to treat gays unequally. The only thing allowing gays to marry will do for the gay rights movement will be to further the never-ending changing of the law back and forth that gays can marry, gays can’t marry, gays can marry, ad infinitum. In order for a new, better, union to compete with marriage effectively, the definition of marriage should stay the same as how it exists in the minds of all married people alive today, an old-fashioned and stubborn tradition.

More interesting? In that they acquire a veneer of condescension? That they become shellacked in her hypocrisy?

Hmm. Maybe. They also become ever more distasteful.

More interesting? In that they acquire a veneer of condescension? That they become shellacked in her hypocrisy?

Hmm. Maybe. They also become ever more distasteful.

Marriage is not a religious institution, Darby. It is a legal one.

Marriage is not a religious institution, Darby. It is a legal one.

Blake. In Errol Morris’ film ‘Mr. Death’, the main character, Fred Leuchter, a kind of self-made execution expert, sees his work as an art, as well as a service. In Morris’ rendering, the enthralled devotion to the intricacies of executions draws us see that Leuchter – a technician with no actual formal training for half the devices he constructs, an aesthetic designer of electric chairs, hangman platforms, gas chambers, lethal injection devices – is actually possessed not just by a mechanics but by an art. However, as the story continues (and maybe you’ve seen it) Leuchter goes on to become a Holocaust denier, using his ‘expertise’ as an executioner to supposedly prove once and for all that the gas chambers could never have existed. He writes a ‘report’ on his findings that is published all over the world. He testifies at a trial in defence of a Holocaust denier in Canada. And as a result of all this, he loses his job, the only thing that ever mattered to him.

Reading what you’ve said in the conversation above, it struck me that you might think it was wrong for Leuchter to have lost his job at the end of this film. After all, his ‘work’, which is to him nothing but an ‘art’, and which certainly displays the formal structure of one, should not be punished in your logic on account of his ‘beliefs’. And yet it was precisely the ‘expertise’ supplied by his work that enabled him to maintain vital ‘authority’ in his claim that the gas chambers were never existent. In that sense, Leuchter’s ‘art’ is the key to the viability of his beliefs. Moreover, what this film makes you realise – as Leuchter cries victimhood from powerful Jewish interests that have stolen his job from him – is that the idea that believing he should not have lost his job is actually a sort of soft anti-Semitism in itself. Under the seemingly non-ideological notion of ‘fairness’ and the good-intentioned separation of art and politics (i.e. did Leuchter have to lose his job? what did that have to do with his testifying in Canada? isn’t taking his livelihood from him as bad as anything Leuchter did? etc.), Leuchter actually almost convinces you that the consequences that befell him were not authored by his *own* actions. As if he hadn’t mobilised his creativity And the reason he can do this is because he actually isn’t an ideological anti-Semite, he certainly doesn’t hate the Jews in any straightforward way, but nor is he what he insists he is: a private citizen with a certain special aptitude or talent who came to some conclusions some intolerant people didn’t want to hear and now he’s lost everything because of it. Leuchter’s refusal to budge from the ‘truth’ that his talents supposedly divined is itself the sign of the *persistence* of his art. He remains committed to his art, except in exile, unable to practice it. He staked everything, recants nothing and wonders why he is where he is. That’s one of the most profound and strangest conclusions of Morris’ film: how one’s politics can appear like no politics at all.

I bring all this up to illustrate a point in relation to this discussion. The absolutist insistence that finding out Mullarkey supported Prop 8 “doesn’t change the image she painted on the paper” is an example of what I’d call art blindness. I find problematic this idea that artists don’t have to think about the world they’re in, that they don’t have to consider the implications of their work as if their work were not real, in this way we designate the ‘political’. This sentiment that art should be able to do whatever it does, unimpeded. A kind of ludic liberty from all inhibition that seems whoa-transgressive when, in actual fact, it has neutered the very meaning of transgression altogether. It’s especially objectionable when those selfsame artists want their art to be real in so many other ways. They want their art to do things, create sensations, cause damage, cause experience, as if these things aren’t the core of politics. I don’t care much for the inference that beliefs are somehow less dimensional than art, or, perhaps more accurately, that art possesses the power to operate cross-dimensionally in a way beliefs cannot. Art has implications. It repercusses. When someone tells me ‘art is art, beliefs are beliefs’, I also hear them telling me that they want a way to insulate their work from the irksomeness of politics, from the supposed sense of phoney clarity that politics brings. What artist today would cop to the idea that their art is actually ‘racist’ or ‘sexist’ or ‘homophobic’. There is no such thing anymore, apparently. As we live in a post-ideological age of ‘liberal democracy’, so now we live in a post-political age of ‘art without agenda’. The boring types who want to find it in there are usually academics or activists, those dick-softeners. So apparently in a case like Mullarkey’s the evident (and absolutely acceptable) reading of her work as a sort of fag orientalism becomes impossible because the new political correctness says the true progressive view is to understand that art is art, beliefs are beliefs and never the twain shall meet. And if the twain is ever *made* to meet, this is a false effect prompted by the interpretation of people who ‘want’ it there. It’s never in ‘the thing itself’.

I think there is apolitical art but I don’t think there’s ever non-political art. Mainly because I don’t believe in the idea of meaninglessness. Things never ever stop meaning stuff. Things are constantly being real all the time. The reason we’re so fucked up and so fucking confused as well as being so fucking certain is not because we’re mired in meaninglessness (which is itself only a meaning we assign) but rather because of tmeaning’s refusal to stop, the unrelenting meaningfulness of things. And meaning to me is inevitably political, even if its political stance is that he thinks nothing of a certain issue or has nothing to say. Not everything is true and not everything is permitted because not everything is true or permitted for everyone. I want to be clear here, though. Apolitical art isn’t non-political because its politics are necessarily secret or hidden or refused but because its politics are such a facted element of the piece they don’t emerge in the way we usually understand politics broadly. I like lots of apolitical art and do not subscribe to the idea that the apolitical is only an alibi. Also too, I believe that the ideas or forms one deploys in one’s art don’t have to stay assigned to the political constellation they’ve been presented in. I can be influenced by Pound, say, and not be an anti-Semite. I could be influenced by Mullarkey too and not be homophobic. But this isn’t evidence of lack of politics in the work itself but rather a sign of the politics of transfiguration that interpretation, reception and reapplication open up. No work of art is so large it can completely control what you do with it. That doesn’t mean, however, it doesn’t have an architecture inalienably its own.

You yourself admit that the context makes this art more ‘interesting’ for you. It’s a sign in itself that context and interest are inextricably, though perhaps not exclusively, related. So you can be against ‘political entailing’ but my bet is that you also, on some level, feel a political soundness in the art you like and the interest you take in it. I’m sure your political views can be ‘suspended’ if you encounter something that grates against you in art (as we all can) but there’s still the grating itself and the ‘suspension’ as an ideological operation that informs an idea of you as thinker that can ‘get past this’, as an art appreciator and reader who isn’t bound in by the ‘partiality’ of politics, a framework which supplies a political notion of open-mindedness about yourself that lends ‘clear-sightedness’ to your understanding of the art at hand, and art in general. Indeed, even the very idea that ‘art should not be political entailed’ must seem innately progressive to you. And this *is* politics. Not civil rights politics, not conservative/liberal politics, but still politics. A philosophical politics. The politics of non-necessitation.

One last thing. In Morris’ film, long before Leuchter becomes a Holocaust denier, his designer’s artistry is dependent on his acceptance of the death sentence. He is for the death penalty, he says, but one of the key elements of his execution equipment design is to make these objects as efficient and mechanically reliable as possible to ensure that the suffering of those who are executed is reduced to an absolute minimum. Leuchter takes pride in the humanity of this. He tells stories of execution malfunction where prisoners have been fried alive in electric chairs, been dosed insufficiently with lethal injections, lived through their hanging. He is for the death penalty but against the agony. Leuchter isn’t a hypocrite to take up this position but he is certainly engaged in a deep and complicated political practice here. And, in the end, we find that the reason his ‘art’ feels so lost to him is because he can’t make ‘working’ execution equipment anymore. It’s not the same with no one to kill. And for those of us who cannot ‘stop’ seeing politics, that is the difficult point.

Blake. In Errol Morris’ film ‘Mr. Death’, the main character, Fred Leuchter, a kind of self-made execution expert, sees his work as an art, as well as a service. In Morris’ rendering, the enthralled devotion to the intricacies of executions draws us see that Leuchter – a technician with no actual formal training for half the devices he constructs, an aesthetic designer of electric chairs, hangman platforms, gas chambers, lethal injection devices – is actually possessed not just by a mechanics but by an art. However, as the story continues (and maybe you’ve seen it) Leuchter goes on to become a Holocaust denier, using his ‘expertise’ as an executioner to supposedly prove once and for all that the gas chambers could never have existed. He writes a ‘report’ on his findings that is published all over the world. He testifies at a trial in defence of a Holocaust denier in Canada. And as a result of all this, he loses his job, the only thing that ever mattered to him.

Reading what you’ve said in the conversation above, it struck me that you might think it was wrong for Leuchter to have lost his job at the end of this film. After all, his ‘work’, which is to him nothing but an ‘art’, and which certainly displays the formal structure of one, should not be punished in your logic on account of his ‘beliefs’. And yet it was precisely the ‘expertise’ supplied by his work that enabled him to maintain vital ‘authority’ in his claim that the gas chambers were never existent. In that sense, Leuchter’s ‘art’ is the key to the viability of his beliefs. Moreover, what this film makes you realise – as Leuchter cries victimhood from powerful Jewish interests that have stolen his job from him – is that the idea that believing he should not have lost his job is actually a sort of soft anti-Semitism in itself. Under the seemingly non-ideological notion of ‘fairness’ and the good-intentioned separation of art and politics (i.e. did Leuchter have to lose his job? what did that have to do with his testifying in Canada? isn’t taking his livelihood from him as bad as anything Leuchter did? etc.), Leuchter actually almost convinces you that the consequences that befell him were not authored by his *own* actions. As if he hadn’t mobilised his creativity And the reason he can do this is because he actually isn’t an ideological anti-Semite, he certainly doesn’t hate the Jews in any straightforward way, but nor is he what he insists he is: a private citizen with a certain special aptitude or talent who came to some conclusions some intolerant people didn’t want to hear and now he’s lost everything because of it. Leuchter’s refusal to budge from the ‘truth’ that his talents supposedly divined is itself the sign of the *persistence* of his art. He remains committed to his art, except in exile, unable to practice it. He staked everything, recants nothing and wonders why he is where he is. That’s one of the most profound and strangest conclusions of Morris’ film: how one’s politics can appear like no politics at all.

I bring all this up to illustrate a point in relation to this discussion. The absolutist insistence that finding out Mullarkey supported Prop 8 “doesn’t change the image she painted on the paper” is an example of what I’d call art blindness. I find problematic this idea that artists don’t have to think about the world they’re in, that they don’t have to consider the implications of their work as if their work were not real, in this way we designate the ‘political’. This sentiment that art should be able to do whatever it does, unimpeded. A kind of ludic liberty from all inhibition that seems whoa-transgressive when, in actual fact, it has neutered the very meaning of transgression altogether. It’s especially objectionable when those selfsame artists want their art to be real in so many other ways. They want their art to do things, create sensations, cause damage, cause experience, as if these things aren’t the core of politics. I don’t care much for the inference that beliefs are somehow less dimensional than art, or, perhaps more accurately, that art possesses the power to operate cross-dimensionally in a way beliefs cannot. Art has implications. It repercusses. When someone tells me ‘art is art, beliefs are beliefs’, I also hear them telling me that they want a way to insulate their work from the irksomeness of politics, from the supposed sense of phoney clarity that politics brings. What artist today would cop to the idea that their art is actually ‘racist’ or ‘sexist’ or ‘homophobic’. There is no such thing anymore, apparently. As we live in a post-ideological age of ‘liberal democracy’, so now we live in a post-political age of ‘art without agenda’. The boring types who want to find it in there are usually academics or activists, those dick-softeners. So apparently in a case like Mullarkey’s the evident (and absolutely acceptable) reading of her work as a sort of fag orientalism becomes impossible because the new political correctness says the true progressive view is to understand that art is art, beliefs are beliefs and never the twain shall meet. And if the twain is ever *made* to meet, this is a false effect prompted by the interpretation of people who ‘want’ it there. It’s never in ‘the thing itself’.

I think there is apolitical art but I don’t think there’s ever non-political art. Mainly because I don’t believe in the idea of meaninglessness. Things never ever stop meaning stuff. Things are constantly being real all the time. The reason we’re so fucked up and so fucking confused as well as being so fucking certain is not because we’re mired in meaninglessness (which is itself only a meaning we assign) but rather because of tmeaning’s refusal to stop, the unrelenting meaningfulness of things. And meaning to me is inevitably political, even if its political stance is that he thinks nothing of a certain issue or has nothing to say. Not everything is true and not everything is permitted because not everything is true or permitted for everyone. I want to be clear here, though. Apolitical art isn’t non-political because its politics are necessarily secret or hidden or refused but because its politics are such a facted element of the piece they don’t emerge in the way we usually understand politics broadly. I like lots of apolitical art and do not subscribe to the idea that the apolitical is only an alibi. Also too, I believe that the ideas or forms one deploys in one’s art don’t have to stay assigned to the political constellation they’ve been presented in. I can be influenced by Pound, say, and not be an anti-Semite. I could be influenced by Mullarkey too and not be homophobic. But this isn’t evidence of lack of politics in the work itself but rather a sign of the politics of transfiguration that interpretation, reception and reapplication open up. No work of art is so large it can completely control what you do with it. That doesn’t mean, however, it doesn’t have an architecture inalienably its own.

You yourself admit that the context makes this art more ‘interesting’ for you. It’s a sign in itself that context and interest are inextricably, though perhaps not exclusively, related. So you can be against ‘political entailing’ but my bet is that you also, on some level, feel a political soundness in the art you like and the interest you take in it. I’m sure your political views can be ‘suspended’ if you encounter something that grates against you in art (as we all can) but there’s still the grating itself and the ‘suspension’ as an ideological operation that informs an idea of you as thinker that can ‘get past this’, as an art appreciator and reader who isn’t bound in by the ‘partiality’ of politics, a framework which supplies a political notion of open-mindedness about yourself that lends ‘clear-sightedness’ to your understanding of the art at hand, and art in general. Indeed, even the very idea that ‘art should not be political entailed’ must seem innately progressive to you. And this *is* politics. Not civil rights politics, not conservative/liberal politics, but still politics. A philosophical politics. The politics of non-necessitation.

One last thing. In Morris’ film, long before Leuchter becomes a Holocaust denier, his designer’s artistry is dependent on his acceptance of the death sentence. He is for the death penalty, he says, but one of the key elements of his execution equipment design is to make these objects as efficient and mechanically reliable as possible to ensure that the suffering of those who are executed is reduced to an absolute minimum. Leuchter takes pride in the humanity of this. He tells stories of execution malfunction where prisoners have been fried alive in electric chairs, been dosed insufficiently with lethal injections, lived through their hanging. He is for the death penalty but against the agony. Leuchter isn’t a hypocrite to take up this position but he is certainly engaged in a deep and complicated political practice here. And, in the end, we find that the reason his ‘art’ feels so lost to him is because he can’t make ‘working’ execution equipment anymore. It’s not the same with no one to kill. And for those of us who cannot ‘stop’ seeing politics, that is the difficult point.

Thank you, David.

The example in the film is not art though, it’s only art-like. You can’t say it’s an art and also a service. The service element of it is what then becomes political, not the art of it. It stops being art as soon as he attempts to use it practically.

The example in the film is not art though, it’s only art-like. You can’t say it’s an art and also a service. The service element of it is what then becomes political, not the art of it. It stops being art as soon as he attempts to use it practically.

Yes.

I’m not sure what I’m trying to do with that comment. It’s devil’s advocate a little. I don’t stand by it because the idea of something separate than marriage that can exist alongside marriage and be so essentially close to being marriage is kind of silly. I’m trying to argue that it’s possible to vote yes on 8 and still be aggressively pro gay rights, to see if that argument is possible, because it doesn’t seem like anyone tries to do that. It bothers me how quickly one-sided the issue becomes for the left-wing and it always seems overly emotionally heated as retribution for an implied homophobic Bush agenda instead of looking at the issue rationally and what are its real implications, consequences. I don’t like categorically voting against something because I don’t like how it got onto a ballot. In my head, I go around and around and it’s like the most complicated issue I’ve ever thought about.

Yes.

I’m not sure what I’m trying to do with that comment. It’s devil’s advocate a little. I don’t stand by it because the idea of something separate than marriage that can exist alongside marriage and be so essentially close to being marriage is kind of silly. I’m trying to argue that it’s possible to vote yes on 8 and still be aggressively pro gay rights, to see if that argument is possible, because it doesn’t seem like anyone tries to do that. It bothers me how quickly one-sided the issue becomes for the left-wing and it always seems overly emotionally heated as retribution for an implied homophobic Bush agenda instead of looking at the issue rationally and what are its real implications, consequences. I don’t like categorically voting against something because I don’t like how it got onto a ballot. In my head, I go around and around and it’s like the most complicated issue I’ve ever thought about.

Darby. I can’t say I agree at all with the idea that art ends at the moment that practical use begins. For instance, propaganda poster artists in service of the state during WW2 are artists to me, period, even if their work was designated with a wholly political task. But even if I were to accept your point, what I said above would still hold true. Leuchter is employed to perform a service by the state, but his ontologisation of that service as an aesthetic enterprise that showcases *his own* ability and skill, not the institution’s, his commitment to the death equipment construction as an end of his existence in itself, his fetishistoc love for the design aspect of his work and for its reconceptualisation of institutionalised death, are entirely artistic. So actually, it’s the opposite: it ‘stops’ being a service the moment he transforms it into an art. It’s not art-like; it’s service-like. Or, as I would claim, it remains both at once, and the tension of the *comfort* between those two is a large part of what the film explores. Which is what is political.

Darby. I can’t say I agree at all with the idea that art ends at the moment that practical use begins. For instance, propaganda poster artists in service of the state during WW2 are artists to me, period, even if their work was designated with a wholly political task. But even if I were to accept your point, what I said above would still hold true. Leuchter is employed to perform a service by the state, but his ontologisation of that service as an aesthetic enterprise that showcases *his own* ability and skill, not the institution’s, his commitment to the death equipment construction as an end of his existence in itself, his fetishistoc love for the design aspect of his work and for its reconceptualisation of institutionalised death, are entirely artistic. So actually, it’s the opposite: it ‘stops’ being a service the moment he transforms it into an art. It’s not art-like; it’s service-like. Or, as I would claim, it remains both at once, and the tension of the *comfort* between those two is a large part of what the film explores. Which is what is political.

something practical can be art, but the meaning of it tends to surround the practicality. A car can be beautiful, can be art, but the meaning of the car tends to be its purpose, or atleast depends on its purpose. Purposeless art is freer to be meaningless.

I’m not speaking for Blake by the way, the comment was addressed to him.

What are we even talking about here? Meaningful ness less etc. Sigh.

something practical can be art, but the meaning of it tends to surround the practicality. A car can be beautiful, can be art, but the meaning of the car tends to be its purpose, or atleast depends on its purpose. Purposeless art is freer to be meaningless.

I’m not speaking for Blake by the way, the comment was addressed to him.

What are we even talking about here? Meaningful ness less etc. Sigh.

David- thank you so much for everything you’ve written. I’m sorry it’s late here and I have to fly to Chicago in the morning, so you’re not going to get the proper response you deserve–not from me, at least, but for whatever it’s worth to you, I really appreciate your having weighed in.

David- thank you so much for everything you’ve written. I’m sorry it’s late here and I have to fly to Chicago in the morning, so you’re not going to get the proper response you deserve–not from me, at least, but for whatever it’s worth to you, I really appreciate your having weighed in.

I don’t know though, I still don’t buy that art has the kind of implication you are talking about. Your example only has implication because it had a service other than art. If it was just art, he wouldn’t have lost his job because he wouldn’t have had a job. His art was blended into a system that began to use and depend on it. Once that happens, you can’t apply the same notions of art to it anymore.

Why is this bad?

Also, I don’t think of it as trying to be politically correct. For me, to remove meaning or politics from art is a way of opening art up, so I guess progressive in a sense, to free it from traditional limits. As soon as all my art is supposed to convey only my beliefs, then I am limited and I am bored and I am quitting art because what’s it for now? Now its dangerous because I’m not allowed to change my beliefs because there’s this thing out there defining me by this belief. Art is just an expression of something, but that something shouldn’t carry the weight of the rigid stance of the artist’s belief. Everything you are saying is only bad if there is some kind of dependence our society has on art to ‘do’ something for us, to implicate or something, but art doesn’t do this, it’s too subjective to rely on for this, it’s too meaningless. Why ‘can’t’ art just be art? What is the repercussion?

I don’t know though, I still don’t buy that art has the kind of implication you are talking about. Your example only has implication because it had a service other than art. If it was just art, he wouldn’t have lost his job because he wouldn’t have had a job. His art was blended into a system that began to use and depend on it. Once that happens, you can’t apply the same notions of art to it anymore.

Why is this bad?

Also, I don’t think of it as trying to be politically correct. For me, to remove meaning or politics from art is a way of opening art up, so I guess progressive in a sense, to free it from traditional limits. As soon as all my art is supposed to convey only my beliefs, then I am limited and I am bored and I am quitting art because what’s it for now? Now its dangerous because I’m not allowed to change my beliefs because there’s this thing out there defining me by this belief. Art is just an expression of something, but that something shouldn’t carry the weight of the rigid stance of the artist’s belief. Everything you are saying is only bad if there is some kind of dependence our society has on art to ‘do’ something for us, to implicate or something, but art doesn’t do this, it’s too subjective to rely on for this, it’s too meaningless. Why ‘can’t’ art just be art? What is the repercussion?

Darby. Hey. In terms of Leuchter, the point I was making in regard to his job loss was that it was a consequence of his way of practicing his job as an artist, as an impresario of execution techniques, a death artist. And that his response to the consequences of his actions in order to escaoe culpability is to appeal to the audience on the grounds that his work had nothing to do with his beliefs when it had everything to do with them. It was specifically relating to the idea above that Mullarkey’s work has no baring on her political principles that I brought this example up. So it isn’t meant to be indicative of all cases of art and service. But when you say that once “his art was blended into a system that began to use and depend on it…you can’t apply the same notions of art to it anymore”, I have to disagree. By that same logic, any writer who writes to get published can no longer be considered an artist, which is absurd. Likewise, any author that *does* consciously write a work that aims at a specific political interrogation – like Brian Evenson’s ‘Father of Lies, as Justin mentioned above, or Robert Coover’s ‘The Public Burning’, to name another – can no longer be called an artist because they aren’t being ‘free’, or ‘opening art up’; instead, they’re putting ‘this thing out there that defines them by their belief’. And that seems to me to be totally untenable as well. I think what maybe troubles you about the Leuchter example is that he doesn’t look like what you’d think of as a ‘typical’ artist. But the idea that a functionary who should amount to little more than a cross between a bureaucrat and an engineer can fully animate himself as an artist – not by doing the work he’s been assigned to do but by aesthetising the assignment into something existential – is one of the points of Morris’ film. (Tangentially, it’s also a point about the technocrats he worked the Holocaust.) Leuchter crosses into Holocaust denial because he thinks he’s mastered the methodological possibilities of death. He thinks he knows how death works. And he thinks this because he has turned his execution work into a form of installation art that distils the essence of death down in close quarters under his control.

To your other points. For me, art can’t help but ‘do’ things. It isn’t about what we *want* it to do at all. Art suffers an obsessive-compulsive disorder of doing; it can’t help itself but do things all the time. Above you said you’d want to be dead if you started asking the three questions Justin listed of the art that you ‘experience’. You used that word. You seem to feel that you experience art. Me too. But yhe only way art could do absolutely nothing for you is if you had no sense that you had ever experienced art at all. I won’t go on to prescribe what art ‘does’ or what its ‘implications’ are or what its ‘repercussions’ are. Not only because that would be assigning a notion of what I think they *should* be but also because I don’t need to. All I’m saying here is that it does ‘do’, that it implicates and repercusses, often in ways that broader society finds extraneous and useless and wasteful and indulgent. That’s a claim I stand by.

This brings me to another of your points. I think you’re right to be critical of a society that depends on art to ‘do’ things for it because what that largely ends up meaning is that society wants art to only do those things it prescribes it to do. The reason Leuchter ‘embarrassed’ the penal system on becoming a Holocaust denier was precisely because he acted beyond the station assigned to him and inadvertently inferred an alliance of values (between denials of life and denials of death, between institutional murder machines, extreme and habitual) that the authorities would like to believe is not institutionally there. But I don’t think any of that has bearing exactly on my general contention that art can’t help but do stuff. To my mind, the fact that art has implication and that it repercusses is a non-voluntary aspect of its eventedness or objectivity as ‘art’. Let me be clearer. When I say eventedness here, I mean its manifestation as experience, and by objectivity, I mean its reality in the world. Art is subjective, sure, but to say something is subjective these days seems to be the same as saying something is open to any interpretation ever *at all*. That isn’t true. Not *any* interpretation. I can’t read Finnegan’s Wake and say, ‘This is Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’.” Even the expression of that claim itself doesn’t make much sense because how would I know what ‘Death in Venice’ is to say that ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ is actually it? Something else already exists in the place of Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’. My point being that the artwork called ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ by James Joyce has an objective, independent existence that I am unable to muscle out of the way with a subjective proclamation that it is in fact, and always has been in fact, Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’, or vice versa. Having accepted that Joyce’s book has its own life, I might interpret the internals of Joyce’s ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ into infinity, in a whole jumble of ways beyond my ability to enumerate here, because I as one person could never know them all. But whatever that book may be found to contain in it for so long as it exists, it only can contain its multitudes inside the boundaries of the object that it is, boundaries which will impinge on it everywhere. In this way, all art may not be definable but all art is definite. This curious combination of infinity and restriction is its politics.

This may be seen as a bad thing. But I don’t view it that way at all. How come ‘limits’ are seen as so automatically negative? Yes, Darby, I’m sorry to say you are limited. As am I. That is neither a bad nor a boring thing. Form, for instance, is a limit. And limits may also have their limits. Past the limits you negate there are other limits that arise in the negation. Old limits return as new horizons which become old limits again as soon as they are dispensed with as horizons. Some limits never relent but the way the forced experience of them is undertaken becomes a frontier. That a work of art of yours would exist in the world, ‘defining’ you out there, does not compel you to remain true to any beliefs it may exhibit. Its existence out there in that way may in fact draw you through your scrutiny of your beliefs to change them. Or it may wed you to them more fiercely by showing you just what it is you believe. Or it may illuminate mental operations you had but never quite knew you did until you were able to sense them through how art had processed them. Mysteriousness does not have to vanish because the concept of belief is introduced. Nor does art only become a mimetic copy of beliefs, whatever they might mean. Nor do beliefs somehow eclipse whatever else may turn up in art. Beliefs aren’t discrete things in that way. They are certainly not the same thing as intentions. And they aren’t ‘against’ art in that way. Their connection to art is often rude but rarely simple.

One other thing. If one implication here is meant to be that maybe Mullarkey was pro-gay and now is not, I don’t buy it. Not only because the ballerina style burlesque of the pictures suggests otherwise but because, as per Justin’s superb reading, the art was conducted not as an exercise in exploring or rendering the gay *claims* of the Parade but as a ‘moral lesson’ in the ludic (which, unsurprisingly, is not far for Mullarkey from the ludicrous; hence, her support for Prop 8, I’d suppose, because these men and women *married* is ridiculous). It reminds me of Zizek’s thoughts on the chocolate laxative. Just as, with that product, you can relieve your condition while eating more of the flavour of something that causes the condition in the first place, Mullarkey can create art that absorbs the spectacle of queerness and which seems to purge any idea of the dread of gays, even and perhaps especially to herself, even as she engages in the politics of disenfranchisement that homophobia in its current American guise thrives on.

Darby. Hey. In terms of Leuchter, the point I was making in regard to his job loss was that it was a consequence of his way of practicing his job as an artist, as an impresario of execution techniques, a death artist. And that his response to the consequences of his actions in order to escaoe culpability is to appeal to the audience on the grounds that his work had nothing to do with his beliefs when it had everything to do with them. It was specifically relating to the idea above that Mullarkey’s work has no baring on her political principles that I brought this example up. So it isn’t meant to be indicative of all cases of art and service. But when you say that once “his art was blended into a system that began to use and depend on it…you can’t apply the same notions of art to it anymore”, I have to disagree. By that same logic, any writer who writes to get published can no longer be considered an artist, which is absurd. Likewise, any author that *does* consciously write a work that aims at a specific political interrogation – like Brian Evenson’s ‘Father of Lies, as Justin mentioned above, or Robert Coover’s ‘The Public Burning’, to name another – can no longer be called an artist because they aren’t being ‘free’, or ‘opening art up’; instead, they’re putting ‘this thing out there that defines them by their belief’. And that seems to me to be totally untenable as well. I think what maybe troubles you about the Leuchter example is that he doesn’t look like what you’d think of as a ‘typical’ artist. But the idea that a functionary who should amount to little more than a cross between a bureaucrat and an engineer can fully animate himself as an artist – not by doing the work he’s been assigned to do but by aesthetising the assignment into something existential – is one of the points of Morris’ film. (Tangentially, it’s also a point about the technocrats he worked the Holocaust.) Leuchter crosses into Holocaust denial because he thinks he’s mastered the methodological possibilities of death. He thinks he knows how death works. And he thinks this because he has turned his execution work into a form of installation art that distils the essence of death down in close quarters under his control.

To your other points. For me, art can’t help but ‘do’ things. It isn’t about what we *want* it to do at all. Art suffers an obsessive-compulsive disorder of doing; it can’t help itself but do things all the time. Above you said you’d want to be dead if you started asking the three questions Justin listed of the art that you ‘experience’. You used that word. You seem to feel that you experience art. Me too. But yhe only way art could do absolutely nothing for you is if you had no sense that you had ever experienced art at all. I won’t go on to prescribe what art ‘does’ or what its ‘implications’ are or what its ‘repercussions’ are. Not only because that would be assigning a notion of what I think they *should* be but also because I don’t need to. All I’m saying here is that it does ‘do’, that it implicates and repercusses, often in ways that broader society finds extraneous and useless and wasteful and indulgent. That’s a claim I stand by.

This brings me to another of your points. I think you’re right to be critical of a society that depends on art to ‘do’ things for it because what that largely ends up meaning is that society wants art to only do those things it prescribes it to do. The reason Leuchter ‘embarrassed’ the penal system on becoming a Holocaust denier was precisely because he acted beyond the station assigned to him and inadvertently inferred an alliance of values (between denials of life and denials of death, between institutional murder machines, extreme and habitual) that the authorities would like to believe is not institutionally there. But I don’t think any of that has bearing exactly on my general contention that art can’t help but do stuff. To my mind, the fact that art has implication and that it repercusses is a non-voluntary aspect of its eventedness or objectivity as ‘art’. Let me be clearer. When I say eventedness here, I mean its manifestation as experience, and by objectivity, I mean its reality in the world. Art is subjective, sure, but to say something is subjective these days seems to be the same as saying something is open to any interpretation ever *at all*. That isn’t true. Not *any* interpretation. I can’t read Finnegan’s Wake and say, ‘This is Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’.” Even the expression of that claim itself doesn’t make much sense because how would I know what ‘Death in Venice’ is to say that ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ is actually it? Something else already exists in the place of Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’. My point being that the artwork called ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ by James Joyce has an objective, independent existence that I am unable to muscle out of the way with a subjective proclamation that it is in fact, and always has been in fact, Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’, or vice versa. Having accepted that Joyce’s book has its own life, I might interpret the internals of Joyce’s ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ into infinity, in a whole jumble of ways beyond my ability to enumerate here, because I as one person could never know them all. But whatever that book may be found to contain in it for so long as it exists, it only can contain its multitudes inside the boundaries of the object that it is, boundaries which will impinge on it everywhere. In this way, all art may not be definable but all art is definite. This curious combination of infinity and restriction is its politics.