Interview with M.E. Parker of the Camera Obscura Journal of Literature & Photography

I’ve always been curious about the darkroom where literary magazines come together. This is a series of interviews engaging, talking, and sometimes annoying editors about their magazines. How did they come about, what do they hate about editing, and what do they love most about it? This is the second in the series and I talked with M.E. Parker of the Camera Obscura Journal of Literature & Photography. It’s by far one of the most beautiful literary magazines around with riveting photography that goes hand-in-hand with some amazing voices. Seriously, the covers kick ass and the stories rip you open from inside and your guts are hanging out and you smile, “Cheese,” for the camera because you want to capture that brief moment where inspiration bisects into awe and mesmerized nausea from having been split open. A brief description on their site states they are: “an independent literary journal and internet haunt featuring contemporary literary fiction & photography. Contributors include established, as well as, emerging writers and photographers.”

As a brief bio and introduction to M.E. Parker:

M.E. Parker is a writer, an editor, web designer, and a carpenter who imagines a world of wooden computers with leather bound keyboards. His short fiction has come up for air in numerous print publications and Internet haunts. He is the founding Editor of Camera Obscura Journal of Literature & Photography. www.meparker.com

***

PTL: When and how did you first come up with the idea of starting the Camera Obscura Journal of Literature and Photography?

M.E. Parker: As is often the case with grand notions conceived in the mental stupor of Belgian Monk brewed beer, I first envisioned a glorious, indescribable tome, pared the following day by the limits of funds, time, and logistics with a few basic principles to guide it. Mostly I wanted a writer and artist friendly venue where, not only contributors, but submitters as well, really do come first, and the stress of the submission process gives way to levity. And in the process my hope was that we create a great community and journal and have fun on the journey (we are still the only journal with a big red “Bug the Editor” button on the withdraw/submit page).

As the editor, I assembled a team not unlike selecting a crew for a heist:

Me – Captain and story wrangler.

Shane Oshetski – can deconstruct, analyze and ostracize any short story.

Tim Horvath – erudite lover of language and Borges, who might wear tweed as an old man.

Meredith Doench – appreciates variety, enjoys the flaws, offsets Shane.

Kate – my wife and incredible photographer, master negotiator, foiler of plots.

PTL: The photography in the magazine is just incredible. What goes into the selection/curating process for the photographs? Are most/all of them chosen from the Competition?

M.E. Parker: The photography does come from the competition for a variety of reasons. Rather than selecting artwork to showcase on the basis of appeal or to augment the writing as an accessory, I wanted a journal where the photography underwent the same editorial scrutiny and selection criteria as the writing without regard for prevailing aesthetic.

25 Points: Life Cycle

Life Cycle

Life Cycle

by Dena Rash Guzman

Dog On A Chain Press, 2013

69 pages / $10.00 buy from Powell’s

1. Dena Rash Guzman climbs trees and sports cowboy boots and straw hats.

2. Many men drown at sea.

3. All the poems are titled Life Cycle to avoid/create/engender confusion.

4. Handless children populate the poppy pods.

5. DRG has been to China and beyond in search of the muse.

6. Farm weddings do not feature high on her list of favorite events.

7. Bones sleep, are tossed, and itch in these poems.

8. I spent one hot summer in Portland once, some years ago, and did not bump into the poet.

9. I have written several poems lately dealing with loss and aging, and “This is how we forget our ancestors:” shakes the dust off my own family skeletons.

10. DRG reads her poetry live more than most writers I’ve come across, and I’m not sure this is due to her brilliant reading, or Portland, OR, having more readings per square mile than Brooklyn, NY. READ MORE >

October 8th, 2013 / 2:47 pm

Our Prime Vibratory Antennae: A Conversation with Will Alexander

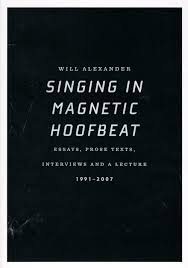

Will Alexander is a visionary and ecstatic writer whose most recent book is Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat: Essays, Prose Texts, Interviews and a Lecture, published by Essay Press. Other recent books include Kaleidoscopic Omniscience, Mirach Speaks to His Grammatical Transparents, Inside the Earthquake Palace and Compression & Purity.

Will Alexander is a visionary and ecstatic writer whose most recent book is Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat: Essays, Prose Texts, Interviews and a Lecture, published by Essay Press. Other recent books include Kaleidoscopic Omniscience, Mirach Speaks to His Grammatical Transparents, Inside the Earthquake Palace and Compression & Purity.

Alexander writes in “Spirit and Practice,” an essay from Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat, “Being menaced by consciousness, the poet finds that the magnetic inscription of words on the page is only part of a continuum. One’s every movement, one’s every despair, is empowered by a wild illuminant rush which burns at the base of one’s character. This is the praxis of spiritus, the praxis of breath, in the simultaneous realms of the diurnal and the oneiric. This constant awareness seems always empowered by a surreptitious sun emitting its power through the aural canals. And the raw material of life is always transmuted by these aural rays. And because of the fire at this sensitive level, one is continuously placed in temperamental combat against the quotidian carnivore, against its reflexive muscle of fact.”

Alexander’s prolific body of work radiates radiance and exemplifies a type of luminosity that seems extremely rare in this world. His verbal flights soar far above the quotidian to a place of vision. Alexander’s use of language is alchemical and talismanic, relating to mental travel through the expansion of awareness and the unfolding of alternate modes of perception. I’d like to thank Will Alexander for providing a way to see, a way to facilitate the envelopment of energy, and for engaging me in this discussion.

***

Chris Moran: Your writing often takes me to remote sectors of the psyche where the language of poetry is not the exception but the primary ruling principle. This has something to do with your expansive vocabulary, which often incorporates the language of astronomy, geology, mathematics, alchemy, botany, mythology, geography, and many other fields. Your use of language goes far beyond the ‘neuro-linguistic programming’ that can stifle the imagination. It feels akin to scrying, and I sense there is something deeply alchemical going on. How is this lens of perception attained, where poetry is indistinguishable from philosophy? Also, do you see language as divinatory?

Will Alexander: When language is felt as a living intelligence it quickens as one internally develops. One can feel its spontaneity like a drone in one’s system. For me, it magnetizes itself to different genres, and to various branches of knowledge. All knowledge springs from the 26 letters of the alphabet, being a poet I am naturally magnetized to its spectrum. Being free, I can range across its field of expression, which includes medicine, astronomy, botany, history, music, cinema, mysticism, architecture. It’s an infinite and evolving list. I’m picking up murmurs all the time. In this sense as I write language takes on an alchemic personality, like an Amazonian flooding replete with the ferocity and power of aboriginal presence. A power yes, but not unlike the mathematics which the old Kemetians used in constructing the pyramids. A living word is not unlike a living number creating a pulsing construct, be it a piece of writing or a pyramid. In this sense creative language is not adverse to philosophical utterance of the vatic.

CM: It’s not unusual to come across words in your poems that I’m unfamiliar with, and many of your books feature a glossary. What you do reminds me of Hart Crane’s dictum to “create new words, never before spoken and impossible to actually enunciate.” This goes far beyond the saturation of elemental forces, as it incorporates planetary and cosmic energy. Where does this knowledge come from? Is it necessary to access alternate modes of perception in order for poetry to process knowledge, or for a poet to embody knowledge? How do you attain this multidimensional framework?

WA: I’ve been engaged in a praxis sustained across duration. I’ll call it in this context poetic yoga. I remain in poetic trance day and night. It is a living world. As I stated earlier the poetic is always murmuring to such an extent that I feel its palpable presence within me. It is a presence which was first introduced to me when I learned about circular breathing. When one can breathe through one’s medium to such a degree that quotidian distraction can gain no entry. One then embodies whatever one is writing on to such a degree that the specific nature of the subject at hand ignites from the root being engaged by the imagination takes on the tenor of the unexpected. The unexpected charged with magnetism which naturally attracts energies from what the Occidental mind calls the invisible. And it is by means of this invisibility that one can intermingle knowledges and poetically contact new lingual dimensions which ignite new synapse firings in the cortex, which can’t be predicted in an a-priori manner since organic creation carries spontaneous warmth as its resonance and by its very nature cannot be chronicled as one would abstractly add or transpose a superimposed structure replete with in-built boundary.

Interview: Sally Delehant & Emily Pettit

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Word is bond.

***

Sally Delehant: The title of the chapbook begins with the word “because” which positions the reader to assume a “why” question floats in the background of the text. I’m wondering what you think that question might be? Does it have to do with why we curl up to a specific person or part of our world? Or is the title perhaps an answer to the big question hanging above all of us — “Why write a poem?” Someone smarter than I am said in a poetry workshop once that on a basic level a poem works out or goes deeper into some kind of anxiety. Something is either resolved or agitated more. Do you agree? Do these poems work like that?

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

In response to your mention of poems being ways that one might work through or with anxiety, I think poems are often working in this way, being asked to work in this way. In regards to my poems, I’m hesitant to use the word “anxiety” because I feel like I use that word all the time in conversations I have with other people and myself and that its meaning is not containing what I want it to communicate. Or various things the word “anxiety” communicates, I worry negate or dim the things in poems that I’m looking for as a reader and looking to make happen as a writer. A friend recently shared with me the following Borges line, “The metaphysicians of Talon are not looking for truth, nor even an approximation of it; they are after a kind of amazement.” In poems I am looking for amazement rather than truth or an approximation of truth. For me amazement might be experienced through encountering two words, the juxtaposition of which make music to my ear or a striking image to my eye. I am looking to be amazed by a feeling that arises when I encounter the ideas, images and music that I encounter in poems. Why I write poems is to find these things that I am also looking for as reader. Anxiety is everywhere, but something I love about poems is that a poem is a place where I do not need to name anxiety, should I not want to. Naming things can give things power or an agency of sorts and the effects of naming things can be good or bad depending on too many factors for me to list here. Poems are a place where I feel I have control over what my brain and heart give agency to. And to a certain extent I have control over the effects this agency has. I have not found many places outside of writing where I get to experience this sort of control. In the poems in this chapbook there are ideas about anxiety and ideas about ideas about anxiety, but they are existing alongside often adamant ideas that anxiety can be controlled and sometimes productively ignored and denied. What it is taking me a long time to say is, I like how my imagination deals with anxiety more than the way other parts of me deal with it.

Sally Delehant

SD: In the first poem in Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something you write, “I freak out, freak out, freak out, / with a quiet mouth,” and as I trace the freak out through the poem (and chapbook) there seems to be tension between doing/being what one naturally does/is and what one could/should do and be if that makes sense. You can wear a nametag that says Emily or rabbit and in another sense be the “best refrigerator ever” as well as many other things. What I’m clumsily getting around to on this sleepy, Sunday afternoon is that I think part of our humanity tells us we should should should be a certain way and we fear we might be “the most ridiculous person (we) know” as you write later. The most beautiful and comforting thing we can hear is that we are good dogs. The speaker “wants to be a good animal.” She wants to let us know that we “are exactly where we are supposed to be.”

Are there things that make you think you aren’t where you are supposed to be? Without being intrusive I want to ask you one thing that scares you, and then I promise we can talk about the beautiful drawings in the book which I am curious about too. What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?

EP: I’m afraid me talking about fear outside of poems is like encountering a black hole. A hall of mirrors. My brain is exhausting in this way. I’m afraid that outside of my poems I fail to be funny about fear in the way that I want to be. I like that in poems I can feel funny about fear. I think anxiety and fear are absolutely linked. I have never encountered a definition of anxiety that does not use the word fear as a part of that definition. I like that when I’m dealing with fear in my poems, while writing poems, I do not feel anxious. Or if I am feeling something that could be defined as anxiety or fear, I’m not aware of it, or not naming it.

I think the thing that both my poems and my answer to your first question point to is a fear of both the presence and absence of control. It’s a conundrum. And I say conundrum, because I don’t think of a conundrum as hopeless. I like how in language with one word, conundrum, you can communicate a subject and a tone. For example, if you had asked me “What is a thing you are afraid of?” versus “What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?”, to me the first question feels much less scary than the second question. Naming me has given me a louder agency, more loudly bonding me to whatever answer I answer. One word. A word. A name. For me to explore fear or ideas of fear in a poem is a place that I am not as afraid of exploration. Exploration feels not just possible but exciting. In conversation and in prose (like writing this now) I have trouble with this exploration; I feel accountable to ideas leading to resolutions of sorts, resolutions that very possibly do not exist. Resolutions of logic that are not expected in poems. Or are not expected by me in relationship to what I think of as a poem. I’m afraid of many things. I’m very appreciative of a poem being a place where I can have some control over my fears and how they feel to my brain and my heart and my body. I’m very appreciative for getting to write poems and read the poems of others for the ways in which this engagement allows me to escape my fears.

25 Points: Radical Love

Radical Love

Radical Love

by Fanny Howe

Nightboat Books, 2006

627 pages / $19.95 buy from Nightboat Books or Amazon

1. While reading Radical Love I was living close to the ocean and swimming every day. One afternoon I was feeling sad so I swam out farther than usual, surpassing all of my customary stopping-points, until I was so far out that I suddenly doubted if I’d be able to make it back. I recognized in what I was feeling the preliminary symptoms of panic; racing heart, flushed cheeks, repetitive thoughts about the panic I was feeling which only succeeded in increasing the panic. I floated on my back, trying to breath steadily. The stretch of beach I’d walked on only minutes earlier was now impossible to approach, a landscape which in its brazen totality had become not only remote but imaginary.

2. I realized that the ocean was terrifying because it was the opposite of lonely; it was abundant. By traveling so far from the shore I’d become an indistinguishable element of that abundance. The terror of my slow, lucid ego-death coupled with the necessity of moving my legs to keep myself alive was a stronger feeling than any kind of loneliness I’d ever experienced.

3. I arrived at Fanny Howe through an interview she did with Kim Jensen of Bomb Magazine.

4 . In the interview she describes her poetics as a reaching towards the ungraspable, the fragmentary, the bewildering. Her preoccupation is with the bentness of time. The freakish all-possible of moments, the vastness of living in simultaneity. How can two people be in two places at the same time? Or: How do we express actions occurring simultaneously?

5. There is a rare precision to her words. They scrape softly and insistently at a very particular feeling. In feeling it for the first time I realized it was a feeling I had always felt. A familiar estrangement. Like seeing a stranger in a dream for the second time.

6. The feeling is intimate with the abject. Between subject and object, the barely separate, like a limb cast-off or a corpse. It follows that many of the subjectivities in her novels are displaced and marginal; madwomen, children, monks. Kristeva writes that the abject inherently exists apart from the symbolic order of language, as a trauma irreconciliable with subjecthood. Fanny Howe makes a language for which abjection is immanent (a new subjectivity?)

7. A Sensual Metaphysics. There’s a body-depth to her narratives, a sense of being weighted, but not weighed down.

8. “She went to the caravan on her sister’s black bike through the dark and felt this way the happiness of being a hard sea animal that machines its way gracefully through the ecstatic interiors of the outside world.”

9. “She began to harden with the first baby. A firm heel slid across the palm of her hand, under her navel, now like a moonsnail with a cat’s eye at its apex. Her wastes, and the baby’s, moved in opposite directions from the nutrients. Her breasts tightened to tips of pain. She entered her psyche daily on rising…”

10. How do you write from inside madness? Most accounts of people going insane seem to come from after or outside psychosis, stressing the role of narrative as a stabilizing and ultimately redemptive exercise. In these texts there is more of a return to madness through narrative. No one is saved and everyone is ecstatic. READ MORE >

September 26th, 2013 / 2:37 pm

Interview with Angela Leroux-Lindsey of The Adirondack Review

I’ve always been curious about the darkroom where literary magazines come together. This is a series of interviews engaging, talking, and sometimes annoying editors about their magazines. How did they come about, what do they hate about editing, and what do they love most about it? This is the first in the series and I talked with Angela Leroux-Lindsey of The Adirondack Review. The visual imagery is simply stunning. The Adirondack Review is like an art gallery curated online, constantly evolving, fused together with great stories, poetry, and essays. In preparation for the interview, I pretty much went through the entire archives and got a brain dump, Matrix-style, in art and photography. A jolt to the system is what I like feeling with my lit magazines and reading directly from their about page: “The Adirondack Review is an independent online quarterly magazine of literature and the arts dedicated to publishing poetry, fiction, artwork, and photography, as well as interviews, articles, book reviews, and translations. Recently named a ‘great online literary magazine’ by Esquire and a ‘top online journal’ by The Huffington Post, TAR was established in the spring of 2000, with its first issue appearing that summer.”

As a brief bio and introduction to Angela Leroux-Lindsey:

Angela Leroux-Lindsey is editor of The Adirondack Review and senior editor with Black Lawrence Press. She writes for Kirkus Reviews and A&U Magazine, and has contributed essays and stories to phys.org, Animal Farm, Innovation Magazine, NY Metro, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and others. She lives in Brooklyn.

***

PTL: Can you tell us about the review, how did The Adirondack Review first get its inception and how did you first get involved?

Angela Leroux-Lindsey: The magazine has actually been around since the summer of 2000—the founder editor, Colleen Ryor, was sort of a pioneer in never going to print, which is something I’ve always admired. But I didn’t start contributing until 2006 or 2007. At that point Diane Goettel was editing, and when she left to run Black Lawrence Press full-time, I took over. So my first issue was in the winter of 2009. A big part of the appeal was their early commitment to publishing art. I especially love how being online gives us the freedom to publish as much full-color art as we want; in the fall issue, I featured almost 30 images by five different artists and photographers. This is something we could never afford if we had to pay for ink and paper. We also publish poetry, fiction, and works in translation in every issue, a mix of mediums that I think is really lovely. Every time we close I’m sort of delighted to see unexpected threads emerge that tie completely different submissions together: a drawing that evokes the tension of post-apocalyptic familial relationships next to a story that takes place on a placid lake over the course of an afternoon but is really about survival. Discovering these entanglements and bringing so many different people together is so much fun. It’s the best job.

PTL: Each issue is packed with fiction, poetry, and some of the most incredible photography and art I’ve seen. What goes into the curating and selection process?

ALL: Well, like every small lit mag out there, I rely so much on my staff. We all volunteer, which makes it even more amazing that I’ve found a group of people willing to be so thoughtful and imaginative about how we compose issues. Nick Samaras, our poetry editor, came on board when I did and he’s brilliant. Google him, read his poetry, you’ll just swoon over it.

Regarding art, some of it comes in through the submission process, but a lot of it I solicit. Sometimes I’m just scrolling through tumblr and come across a piece that floors me. And I’m always completely thrilled when a big name that I’ve solicited says yes: I mean, Manfred Mohr was on the cover of the summer issue. I was watching some of his animated videos from the 70s on YouTube, and figured I’d send him an email to ask if he’d be interested in featuring some of his new stuff. And he emailed me back within a week and said yes. I’m still excited every time this happens. It’s magical. Richard Mosse is another example. I’m in love with his INFRA series, which is online now.

Really, getting to work with all of these artists and writers is absolutely the best part of having this role. Not just meeting new people and developing friendships—like with you, Peter—which I really value. But living in Brooklyn and getting to hang out with so many writers I admire is killer. You wouldn’t believe the people I’ve met and fallen completely to pieces in front of. I hosted a reading once with Paul Muldoon and could hardly pronounce my own name when I introduced myself. And then to watch emerging writers and artists who have published work with us go on to publish books or exhibit work at major galleries or museums is really awesome. My friend Kit Frick has a completely gorgeous chapbook coming out called Echo, Echo, Light from Slope Editions. We published early versions of a few of these poems in 2011 and I can’t wait to see how they’re incorporated into a collection. And Luba Lukova, a political artist whose work I sought out for the cover of the first issue I edited, will show at MoMA next month. Revisiting these issues and experiencing that kind of folding of time is a cool thing. It makes me think of the larger view of independent publishing as a sort of performance art space in itself.

An Open Letter to Readers and Writers on the Internet Regarding the Founding of El Aleph Press

Dear Internet Readers,

You know that boringly recurrent conversation in which someone laments the end of print and someone else talks about how craftsmanship, design, and embracing new media can actually make small presses more viable and exciting than ever? In that conversation you are the second (more optimistic) person. Or at least you like to hold out hope that that person’s correct. And because of that you really should know about El Aleph Press.

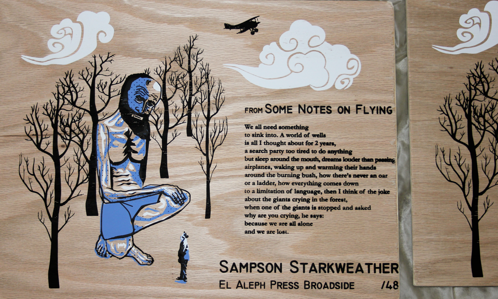

In the interest full disclosure and as proof that I know what I’m talking about, I should say that I’ve known and been friends with El Aleph’s founder/editor, Michael Bagwell, for several years. I like him, I trust his aesthetic. So naturally I was excited to hear that he’d started a press. Then I actually got my hands on the things he was doing and got even more excited. El Aleph makes books, broadsides, t-shirts, and now an anthology. Their website features writing, of course, but also short films and, soon, a whole host of other multimedia work. They’re getting involved in a lot of projects across a range of media, and everything they touch is beautiful and careful and medium-specific.

Let me give two examples of the work El Aleph is putting out. Their first broadside features a short Sampson Starkweather poem with a color illustration printed gorgeously onto solid wood. Their first book, Or Else They are Trees, is a collaboration between Bagwell and the artist Rebecca Miller. It’s similarly gorgeous, a mix of poems and full-color artwork. If there’s an early hallmark of El Aleph’s work it’s that language and design are equally meticulous.

I should also mention that El Aleph is currently looking for submissions for their forthcoming anthology. From what they’ve published and what I know of Bagwell’s aesthetic, you’d be well served to send in formally adventurous works, lyrical weirdness, and texts that are equally surreal and sincere. You should also send reviews, comics and more traditional stories/poems.

All of the information on El Aleph, their projects, and submissions guidelines are available at their website. So check out/submit/support, etc.

Very Best,

Ben

September 24th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Stories Keep Us Warm: How an innovative reading series is firing up the Seattle literary scene

I was recently chosen to perform my story “Trigger” for The Furnace, a Seattle series where one prose writer is invited to read a single piece to completion. The writer performs their piece in front of a live audience, which is simultaneously broadcast over Hollow Earth Radio. By focusing on one writer (rather than several brief readings by multiple people), the series takes a risk in that it really relies on that single person to create a compelling performance and single-handedly drive attendance. What results from that risk is an always interesting, kinda weird, and truly unique listening experience. It also provides a beautiful showcase for the writer and their work, giving them a chance to explore alternative presentation styles—using actors, live musicians, sound effects and other elements to enrich the reading. With its radio broadcast, the series taps into older forms of storytelling by bringing people together to listen, either online or in person (herding us literary cats, in a way). From The Furnace mission statement: “Stories were told around a fire. They kept us warm and created a sense of connection and community.”

It’s really a kind of magical experience to both listen and perform at The Furnace. The Hollow Earth Space is small, but reads as warm and intimate, rather than cramped. And, as a reader, it was cool to know people were listening over the airwaves—friends of mine texted after the reading was done, congratulating me. There have only been five performances so far (which you can listen to on Soundcloud and The Furnace website), but the series has already gained a big following, and been a featured event in the local alternative weekly The Stranger many times. It’s been cool to see a relatively small, but pretty original idea build its audience and reputation in such a short amount of time.

To learn more about how the series got started, and what goes into putting it together, I had a little Q&A with the founder, Corinne Manning. Here’s our conversation:

***

LJH: So can you tell me more about what inspired you to start the series?

CM: As a prose writer it’s often tricky to participate in readings because I’ll have about ten minutes and that means usually cutting a story down, or just reading the first bit–where as ten minutes for a poet means something very different. I wanted to create a series that gave a prose writer the opportunity to read a piece all of the way through, and even get to explore presenting it in innovative ways. The chapbook that’s made for each event and the fact that its broadcast on Hollow Earth Radio is all part of trying to make a disparate literary community feel more cohesive, create a holistic listening experience for the audience member, and also give a writer a real chance to be showcased beyond the ephemeral reading.

LJH: How happy have you been with it so far? Have there been any challenges?

CM: I ran a series with multiple readers before (Other Means in Brooklyn, NY), and though I loved the format of that series and the intention, I’m much happier with the Furnace. There are some really obvious ways in which it’s easier than what I was doing before: it’s quarterly, there’s only one writer to schedule, and because that writer gets showcased in a really special way they take it seriously in a way that I hadn’t witnessed before. My co-coordinator Anca Szilagyi and I have always been lucky to get a really good crowd, which is really exciting because we purposefully try to showcase people who are emerging or who aren’t one of the same eight or so people featuring again and again.

LJH: Thinking more about readings, I’m wondering if you could describe the qualities that you think makes for a great listener experience. Like what makes you go: “Wow, I’m really glad I went to that.”

CM: This is like defining the mystery of the universe! There’s an essay by Frank Conroy where he talks about the relationship between the writer and the reader in a piece of fiction as this collaboration, where both the writer and the reader are putting a certain kind of energy in to make the story happen. The writer, he says, has to put in a little extra work to create space for the reader’s energy to fill the story. Esoteric, I know but I think the same thing happens at a reading. The writer who is performing is engaged in the act of telling the story—and is in a sense performing it. The listeners then too, should want to be there, are more engaged in receiving than just waiting for their friend to be the one who comes up on stage.

September 20th, 2013 / 11:00 am

25 Points: Hunger

Hunger

Hunger

by Knut Hamsun

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008

272 pages / $16.00 buy from Amazon

1. This is an article about Robert Bly’s (b. 1926) translation of Hunger by Knut Hamsun (b. 1859). It was published by FSG in 1967.

2. The cover graphic is the word HUNGER stylized as an open mouth with 2 rows of sharp teeth. I bought my copy in January 2013 from a used bookseller in Toronto. The clerk said it was her favorite book, esp this edition because she liked the cover. The design is not credited in the edition notice.

3. Knut Hamsun is clean shaven and wearing a monocle in a photograph taken in 1890, the year Hunger was first published in Norway. In later photographs he is moustachioed and wears glasses. In the last known photographs of Hamsun he wears a large white beard and squints.

4. The first several times I read Hunger by Knut Hamsun was in a hardcover edition translated by George Egerton aka Mary Chavelita Dunne in 1899. This review is not about that translation, nor is it about the 1996 translation by Sverre Lyngstad.

I am descended from Norwegians but know nothing of the language. This article is not as much a review of the translation itself as it is a discussion of the fact of its publication in 1967.

5. The main introductory essay to Bly’s translation is by Isaac Bashevis Singer (b. 1902) noted Jewish-American author and pioneer of modern Yiddish literature.

“Writers who are truly original do not set out to fabricate new forms of expression,” says Singer, “or to invent themes merely for the sake of appearing new. They attain their originality through extraordinary sincerity.”

6. “People do not love alike, neither do they starve alike.” (Singer).

7. Hunger is about a young man with artistic leanings living in Kristiania, Norway. From biographical details about Hamsun we can guess that the story is based on Hamsun’s own experiences and takes place in in 1879-80.

Hunger itself does not offer much in the way of context. It is a first person account of a young man living alone in a city. He appears to have no awareness of anything outside his own need, which is mostly for food. He is starving and desperate, but the private code by which he lives forbids him from taking work that he considers to be below his abilities.

8. His mental state throughout is ostensibly a result of his being hungry, rather than a symptom of mental illness or PTSD for example. He cycles rapidly through extreme moods: hilarity, despondency, optimism, despair, loneliness, social anxiety etc.

9. Doubt is the driving force behind the narrator’s racing thoughts. His doubt tirelessly regenerates itself. Doubt is what drives the desperation and sets its parameters. It is what keeps need always at the centre.

At every moment he is like a reckless gambler who has already placed his bet before realizing the stakes are too high, and then in a panic must cut his losses before waiting to see the outcome.

“He was a man before his time,” says Singer, “His skepticism, or perhaps it could be called pyrrhonism — doubting even the doubts — belonged to a later era. To Hamsun man was nothing but a chain of moods that kept constantly changing, often without a trace of consistency.”

10. “Fictional heroes who are estranged from their environment seldom emerge lifelike,” says Singer, “With most writers, such heroes are mere shadows, or, at best, symbols. But Hamsun is able to portray both the environment and the alienation, the soil and the extirpation. His heroes have roots even though they cannot be seen.”

There is almost no historical or social/political context in Hunger. In most novels of the era that would be seen as a fault. In Hunger it is seen as a strength.

As a reader I only interact with the narrator’s environment as needed. That is because the novel is not about Norway or Europe: it is about being hungry. READ MORE >

September 19th, 2013 / 2:53 pm