Unteaching in the Creative Writing Classroom

We do a lot of teaching in writing classrooms, but we also do a lot of unteaching. This is particularly true in introductory creative writing classes, where a large percentage of our work is undoing what teachers before us (in elementary and high school) have done.

I want to be clear that I’m not picking on English teachers here. Both of my parents and many of my friends are English teachers and I have the utmost respect for them. They do great work exploring the history and meaning of literature in their classrooms. Typically, though, they are not themselves devoted to the craft of imaginative writing. They’re literature scholars who are asked (sometimes against their will) to do a unit or two on creative writing as part of their curricula. Wisely, teachers in such situations often use the “Creative Writing Unit” as an opportunity to hone students’ skills in spelling, grammar, punctuation, vocabulary, and other fine points of the language. While they may be better off in terms of vocabulary and punctuation skills, there are often negative consequences for their creative compositions.

Below are some examples of these unintended consequences. These are bad habits I’ve seen young writers bring into my classroom and how I’ve tried to help them break free.

READ MORE >

The Best Version of Whoever That Is: A Teaching Philosophy

Ed: Over the coming weeks (and maybe months given the number of posts I’ve received), I’ll be featuring conversations about the teaching of creative writing from teachers, both new and experienced, as well as students, all of whom are trying to answer the question, “How the hell do we teach creative writing?” Our first post comes from Laura van den Berg, author of What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us. –RG

—

For a handful of years I have been teaching creative writing in a variety of settings, mostly academic. I entered into the whole enterprise feeling a touch uneasy about claiming to be able to teach that maybe can’t be taught. My biggest worry was oversimplifying. I knew my students would need to learn the craft fundamentals of fiction, but how could I convey them in a way that does justice to the form that I love, the form that thrills and confounds me on a daily basis? Fast forward a few years and I have some ideas. I always tell my students there are no rules in fiction, only principles. Here are some of my teaching principles:

1. One of the basic problems in introductory-level workshops is that students are grappling with how to talk about what they and their peers put on the page. At the same time students want to come to class with something to say, preferably something smart-sounding (and often they succeed; I am regularly knocked-out by how insightful my students are). This can result in an unhealthy attachment to surface level issues, such as the dreaded questions of plausibility—i.e. “Was it really plausible for Aunt Ida to walk 10 miles in a hurricane? Shouldn’t it have been more like 5?” Unfortunately these questions have little relevance to the larger enterprise of the story. Of course Aunt Ida could have walked 10 miles in a hurricane and if for some reason she could not, that issue can be addressed with a margin note and a click of the keyboard. What the student probably means to say is something like: I don’t believe in the world you’ve created. You’re not convincing me. And questions of world-building are way more fruitful conversation topics than how far someone can walk in a hurricane. I ask that students push themselves—both in their reading and in discussion—beyond the surface, toward those underlying questions. I have gone as far as to ban the word “plausibility” (“likability” is another one) from workshop, as it is so often a euphemism for: “I sense there’s something going on here but I don’t have the language for it, so I’m saying this other thing instead.” Let’s help our students find the language.

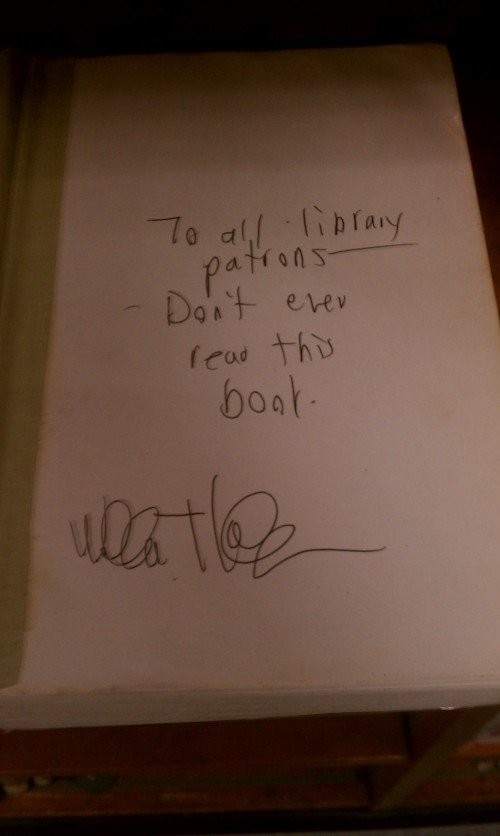

“To all library patrons…”

I was at the Brooklyn Library (central branch) earlier, when walking through the fiction section, I saw Vollmann’s books. I picked up You Bright and Risen Angels, opened it up, and found the following inscription. Unfamiliar with Vollmann’s signature, I looked it up just now using Google images. It’s a match. Pretty sure it’s real. You’d have to be a pretty huge Vollmann fan to know the man’s signature offhand, and then if you were that kind of fan it’s doubtful this would be the inscription used.

from Feedback

Three or four years ago, I was reading an ambitious student story that made very little sense to me. The language was pleasing rhythmically, sonically, but it was all fairly abstract, too. I found myself writing again and again in the margins: Could this be stated just a little more clearly? Could this be a little more concrete/precise? On a single page, some version of the preceding two sentences appeared five times, and I began wondering what a text composed of only my marginalia might look like. After all, students most likely read what I write in the margins as if it is its own kind of text, one comment after another after another. I held on to this idea for some time, and then finally, earlier this spring, I began creating texts from some combination of my marginalia and end notes. A part of me worries I’m betraying the confidence students place in me when they so bravely hand over stories they have written, but a larger part of me feels compelled to share the conversation, however seemingly one-sided it may seem, as a way of demonstrating the dynamic exchange that takes place between readers and writers. I’m calling the series of texts “Feedback.”

Heather Christle’s The Trees The Trees

The Trees The Trees is a wrecking ball covered in flowers. These poems by Heather Christle make me feel, often simultaneously, all of the following things: that I am riding a fucked-up carousal in the middle of the woods, that I am an animal pulling out my own wires, that my skin is a new kind of candy, that my brain and my heart are in a tree and that, somewhere up in that tree, they are kissing, calling each other the wrong names.

The poems look like prose blocks with holes punched in them. If you unfocus your eyes while you read it looks like pieces are missing. Like a puzzle from the thrift store. But what’s missing is what makes these poems right. Consider the line “my friend the golden onslaught married stuff in bloom” from the poem “Happy Birthday To Me.” Nearly each word in this line pushes against the emotional quality of the word next to it, as if the line is trying to break out of its semantic skin. The word “onslaught,” made physical because it is “golden,” sits there in the middle of the line wreaking all kinds of contradictory havoc. The ambiguously casual “stuff” makes the line colloquially wobbly. Then “bloom” comes in with a tender, exuberant punch in the heart, not to mention filling out the line’s weird music. Good parts in a good machine.

Reading The Trees The Trees is akin to the logical disturbance one feels while watching YouTube videos of the late Macho Man. Indeed, the ever-quotable, sequined Savage bewilders and entertains in a surprisingly articulate brand of Dada-esque madness. In an article at espn.com, Bill Simmons sums up Savage’s influence on his sport, noting that “Wrestling moved pretty slowly back then [the mid-80s]: lots of headlocks and clotheslines, lots of rolling around, lots of killed time, lots of fat rolls and labored breathing. Savage murdered that era almost overnight.” Simmons describes Savage as “phenomenally bizarre and undeniably entertaining,” saying that, “You needed a translator even if he was speaking in English.”

July 12th, 2011 / 12:47 pm

Online Literature Calender at Zine-Scene

Zine-Scene is a website devoted to promoting online literature through journal reviews, author spotlights, and its own literary quarterly, which reprints fiction that previously appeared in print only. Keeping with this mission we have launched an Online Literature Calendar. The calendar displays the release dates of online literary magazines and makes finding new literature easy and user friendly.

Zine-Scene is a website devoted to promoting online literature through journal reviews, author spotlights, and its own literary quarterly, which reprints fiction that previously appeared in print only. Keeping with this mission we have launched an Online Literature Calendar. The calendar displays the release dates of online literary magazines and makes finding new literature easy and user friendly.

“Get Well Seymour!” by Joe Meno, Or: Let’s Talk

When I was charged with the task of contributing to this superneat project hyping Akashic Books’ redux of Joe Meno’s short fiction collection, Demons In the Spring, I felt entitled. For years I’d been a pestering cheerleader for Meno’s novels, The Great Perhaps and The Boy Detective Fails. Although the former got a fat, excellent review in the Times, I still felt Meno was somehow criminally under-heralded, a vital voice in need of a louder advocate. So when I got the chance to be that advocate, to ruminate on one of the collection’s stories, “Get Well, Seymour!”—a sad, excellent tale about cruise ships, inevitability, and psychosomatic parrots—here’s what I did:

When I was charged with the task of contributing to this superneat project hyping Akashic Books’ redux of Joe Meno’s short fiction collection, Demons In the Spring, I felt entitled. For years I’d been a pestering cheerleader for Meno’s novels, The Great Perhaps and The Boy Detective Fails. Although the former got a fat, excellent review in the Times, I still felt Meno was somehow criminally under-heralded, a vital voice in need of a louder advocate. So when I got the chance to be that advocate, to ruminate on one of the collection’s stories, “Get Well, Seymour!”—a sad, excellent tale about cruise ships, inevitability, and psychosomatic parrots—here’s what I did:

I sat on the assignment for five months.

June 30th, 2011 / 2:20 pm

I’m Not Going To Make It Through This Life. Okay, Never Mind. Do You Like Ice Cream? : 3 Reviews

i am like october when i am dead poems by steve roggenbuck

18pp published by Steve Roggenbuck (2011)

Steve Roggenbuck is not Robert Frost. His poems avoid forests of metaphors. Although they might give you a woody. Roggenbuck’s poems are not pedestrian, but peripatetic. They get you to think, just a little bit, about murder and loss. They also make you look into a night sky and wonder what you had for lunch or what’s on TV. Roggenbuck’s poems hold up dead flowers, then make you leave the room after declaring that that’s all there is. They are rakish, shake a giant rake to scare you, gather dead leaves outside the church of poetry, walk an elephant into that strange part of you called consciousness. Steve Roggenbuck’s poems will choke your dad for your birthday. They don’t care. They will not answer your calls. They are alive with the memories of killers, wonder what they will harvest, then stuff dogs into garbage trucks. These poems are the eraser of two hundred years of American poetry, the shout at the end of a sentence that seeks always a little bit of anarchy, a car on fire. Roggenbuck’s poems are the beginning of a great career.

Steve Roggenbuck is not Robert Frost. His poems avoid forests of metaphors. Although they might give you a woody. Roggenbuck’s poems are not pedestrian, but peripatetic. They get you to think, just a little bit, about murder and loss. They also make you look into a night sky and wonder what you had for lunch or what’s on TV. Roggenbuck’s poems hold up dead flowers, then make you leave the room after declaring that that’s all there is. They are rakish, shake a giant rake to scare you, gather dead leaves outside the church of poetry, walk an elephant into that strange part of you called consciousness. Steve Roggenbuck’s poems will choke your dad for your birthday. They don’t care. They will not answer your calls. They are alive with the memories of killers, wonder what they will harvest, then stuff dogs into garbage trucks. These poems are the eraser of two hundred years of American poetry, the shout at the end of a sentence that seeks always a little bit of anarchy, a car on fire. Roggenbuck’s poems are the beginning of a great career.

* * *

The Day Was Warm and Blue poems by Richard Loranger

28pp published by Richard Loranger (2002)

Richard Loranger is gay. He remembers the colors, temperatures of his mornings. Some of these simple memories become poems. Like the twenty-eight poems contained in this book. However, Loranger’s poems are not really contained. Or, if they are, they are contained the same way a sky is contained: warm and blue. But, peculiar. Very, very peculiar. Each poem is a tiny ass-fuck on the same day you kill your boss. Each one is there, with you, because there is nothing else to do. This makes them wonderful. Loranger’s poems are pretty butterflies. They flutter through a room and are closely listened to, but only after they have been eaten. They gather dead leaves outside the church of poetry, put them on a shelf, forget them, maybe. If Loranger had the time he would write these poems upon a wall using his own urine. They are that simple and that marvelous. And who knows? Perhaps he already has. Each of these poems are a little song that drifts by. They are the shadow of an acrobat tumbling in air, a cat in each eye. They are a drink of water after an argument, the mystery of television. Doused in gasoline, simple, lyrical, they want to know who’s in charge, will only listen to the secrets of plants, then wait quietly, to get the names they need to celebrate their small fire. Time has nothing to do with them. I mean, who needs time? These poems keep going on and on, each in their little, magnificent way, all warm and blue.

Richard Loranger is gay. He remembers the colors, temperatures of his mornings. Some of these simple memories become poems. Like the twenty-eight poems contained in this book. However, Loranger’s poems are not really contained. Or, if they are, they are contained the same way a sky is contained: warm and blue. But, peculiar. Very, very peculiar. Each poem is a tiny ass-fuck on the same day you kill your boss. Each one is there, with you, because there is nothing else to do. This makes them wonderful. Loranger’s poems are pretty butterflies. They flutter through a room and are closely listened to, but only after they have been eaten. They gather dead leaves outside the church of poetry, put them on a shelf, forget them, maybe. If Loranger had the time he would write these poems upon a wall using his own urine. They are that simple and that marvelous. And who knows? Perhaps he already has. Each of these poems are a little song that drifts by. They are the shadow of an acrobat tumbling in air, a cat in each eye. They are a drink of water after an argument, the mystery of television. Doused in gasoline, simple, lyrical, they want to know who’s in charge, will only listen to the secrets of plants, then wait quietly, to get the names they need to celebrate their small fire. Time has nothing to do with them. I mean, who needs time? These poems keep going on and on, each in their little, magnificent way, all warm and blue.

* * *

Aquarium poems by Ryan W Bradley

26pp published by Thunderclap Press (2010)

Ryan Bradley is straight. He eats lots of spaghetti. He sees pornography everywhere. His poems are a testament to that vision: defiant, sexy, sometimes late for class. It is a teenager’s world. Bombs go off like songs on the radio. And Bradley listens, makes them pretty, finds the wonder in flashing red lights, women falling from the sky, a city on fire. Bradley’s poems attempt to feel things. That is, they are thinking: About the next cigarette, cheerleaders buried under ice, a sudden sensation that slants everything, makes you walk funny. It likes girls, smoke, the Beatles. But best of all, they get depressed in the summer, still believe in the alcoholism of the blues, disguise their social class because these were born poor. Sex and death. It’s all here in these poems. And if you aren’t drunk by page two, you will be by page twenty-six. Drunk and slightly bruised. And touched, lightly. Because Bradley’s hand is light, might even take you far away. Imagine particles, the flash of fireflies, the nakedness of desire—cells rapidly dividing—spread over noodles. These poems are peppered with neighbors singing opera, but Bradley also wants to hear your eyelids closing. He’s sweet. These poems are sweet. All of them, underwater.

Ryan Bradley is straight. He eats lots of spaghetti. He sees pornography everywhere. His poems are a testament to that vision: defiant, sexy, sometimes late for class. It is a teenager’s world. Bombs go off like songs on the radio. And Bradley listens, makes them pretty, finds the wonder in flashing red lights, women falling from the sky, a city on fire. Bradley’s poems attempt to feel things. That is, they are thinking: About the next cigarette, cheerleaders buried under ice, a sudden sensation that slants everything, makes you walk funny. It likes girls, smoke, the Beatles. But best of all, they get depressed in the summer, still believe in the alcoholism of the blues, disguise their social class because these were born poor. Sex and death. It’s all here in these poems. And if you aren’t drunk by page two, you will be by page twenty-six. Drunk and slightly bruised. And touched, lightly. Because Bradley’s hand is light, might even take you far away. Imagine particles, the flash of fireflies, the nakedness of desire—cells rapidly dividing—spread over noodles. These poems are peppered with neighbors singing opera, but Bradley also wants to hear your eyelids closing. He’s sweet. These poems are sweet. All of them, underwater.

– – –

Janey Smith (b. March 30, 1981, Anaheim, California) was born on the same day that President Ronald Reagan was almost assassinated. She likes to think her birth had something to do with it. Janey lives in San Francisco, CA.

June 23rd, 2011 / 2:03 pm

Tales of Woe and Toenails

Yes, I am well aware that the first marathon runner dropped dead for his efforts. If he hadn’t, we wouldn’t go 26.2 miles; we’d go some other outrageous distance that killed its first runner.

Every year a few people die running marathons. Of course, every day ridiculous numbers of people die doing absolutely nothing. I choose to run marathons, and I don’t have a death wish, though I will admit I’m drawn to the drama of distance running. You could die. You could fracture bones, tear muscles, lose toenails. You will definitely suffer, a lot. Cool.

That said, it’s odd to talk about the drama of running because here’s another thing I’ll admit: running is boring. A fellow running buddy of mine once joked that no one has ever sat through the entirety of Chariots of Fire and remained conscious. And this is coming from someone who loves running more than he loves his wife and kids. I’ve never seen Chariots of Fire—in fact, I haven’t seen any movies about runners, and I don’t feel any particular compulsion to do so, despite the fact that my colleagues keep shouting “Prefontaine!” and “Run, Fatboy, Run!” when they see me at work. (People love it when they think they have you figured out; because I run marathons, they’ve decided that every aspect of my life no doubt revolves around running. It could be worse; there was that one year everyone thought I was into cows. Let’s just say I had a very Holstein Christmas.)

Twitter MFA

In which we do a close-reading of a Tweeter’s Tweet draft and assess its tone, theme, synecdoche and narrative arc, among other things. Today’s Tweet draft was written by Drew Kalbach. This is the final installment of Twitter MFA. Thank you for reading.

The Tweet draft:

my face is continually jealous of my face

Drew Kalbach’s Tweet draft utilizes a heavily deconstructed sonnet sequence to describe the dissolution of a romantic relationship between his face and his face. With its ABBA rhyme scheme–the pairing of ‘face’ and ‘face’ and the softly assonant ‘continually’ and ‘jealous’–Kalbach alludes to a Miltonic sonnet in 140 characters or less.