Candide

Candide

by Voltaire

Norton Critical Edition, 1991 / 224 pages Buy from Amazon ($11.56)

Penguin Classics, 1950 / 144 pages Buy from Amazon ($11)

I must have had g-rated goggles on when I first read Voltaire’s Candide because I didn’t remember how violently twisted the book got. Published as satire in 1759, it attacked Leibniz’s idea from his Monadology that this world was the best of all possible worlds. History intertwines with fiction in Candide as the backdrop of the Seven Years’ War and a deadly earthquake in Lisbon that killed more than fifty thousand people fueled Voltaire’s rage. The religious men of his age, the ‘optimists,’ tried to comfort people with the idea that everything, no matter how vile, happened for a greater good as it was driven by a higher power. Dr. Pangloss, Candide’s tutor and an obvious caricature of Leibniz, espouses this belief and Candide carries forward it as a conviction throughout much of the narrative. Voltaire drills in his rebuttal with the violent imagery of something straight out of a Takashi Miike film.

Take for example, Cunegonde, the love of Candide’s life, as she shares her tragic story:

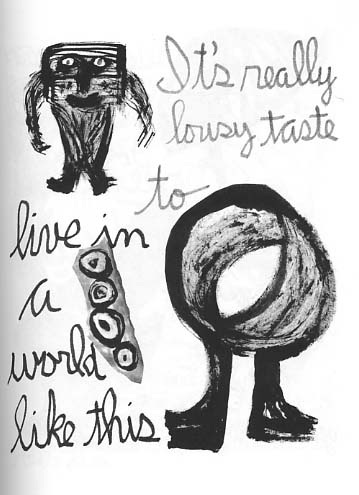

They cut my father’s throat and my brother’s, and made mincemeat of my mother. A great lout of a Bulgar, six foot tall, noticed that I had fainted at the sight of this butchery, and set about ravishing me.

As horrific as this sounds, shortly afterward, they meet an old woman who assures them her misfortunes outweigh theirs. She used to be a princess until her betrothed was poisoned through chocolate. She was then carried off as a slave:

Morocco was swimming in blood when we arrived… I saw my mother and all our Italian ladies torn limb from limb, slashed, and massacred by the monsters that fought for them. All were killed, both captors and captives, my companions, the soldiers, sailors, black, whites, and mulattoes, and finally my pirate chief… I freed myself with considerable trouble from the pile of bleeding corpses…

READ MORE >

Candide

Candide

Doll Studies: Forensics

Doll Studies: Forensics The Forever War

The Forever War A Fan’s Notes

A Fan’s Notes Say Poem

Say Poem Farther Away

Farther Away Oversoul: Stories and Essays

Oversoul: Stories and Essays