Mirror men

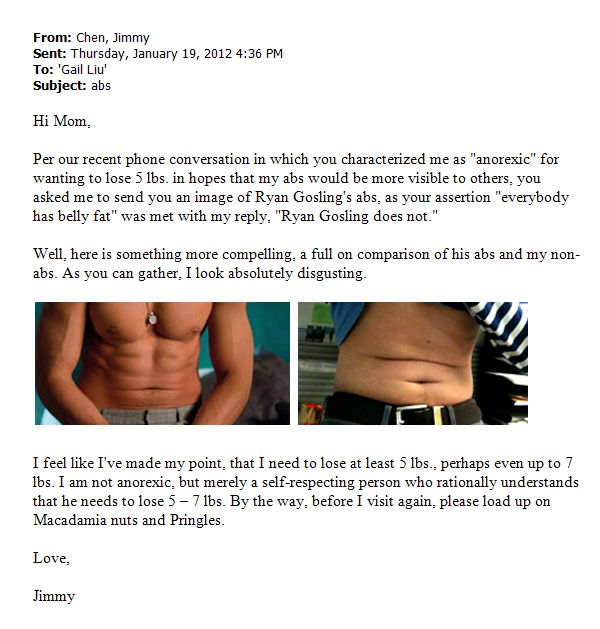

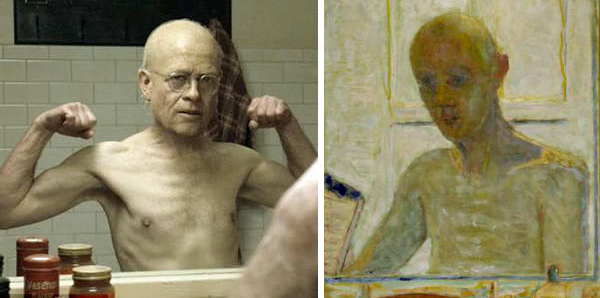

That The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (1922) was posthumously made into a film (2008) may be ironic — to brave a word perhaps deplete of any meaning by now — given the author’s self-perceived degradation of writing for Hollywood as he grew older and financially more dependent in his maintenance of a vapid lifestyle. His last lover was a gossip columnist, proof that blogging has always existed. They say a writer’s best work is in his late twenties, before the soft middle-age limpy interval, but that only a great writer will make his best work near his death, alluding so some moral component and/or mortal imperative of great writing. It is sad to think of a drunk Fitzgerald, a loopy sentimental Hemingway, or a blind ass jibbering Joyce; we look towards Tolstoy, Shakespeare, as examples of work whose maturity lies in correlation with their age. We may see Benjamin Button as an inadvertent commentary on the mediocre artist, the fated infant. In 1935, at the age of 68, Pierre Bonnard painted “Self Portrait in a Shaving Mirror,” two eye socket holes hidden in the shadow of his own face, perhaps seared by the southern France sun of younger days before locking himself in the bathroom — something he may have learned from his wife Marthe, an obsessive compulsive bather (hence, the bathing series), on whom he cheated with one Renée Monchaty, of sunnier disposition. In his paintings of the former, the latter is often hidden at the edge of the canvas, camouflaged in the quivering aggregate of floral brush marks which consumed him. Bonnard didn’t name it “Self Portrait in a Shaving Mirror” — an art historian came along later to distinguish it from the all the other ones, to make discourse when discourse was not intended easier. But it’s hard to comment when you’re dead, and other perilous times as well.

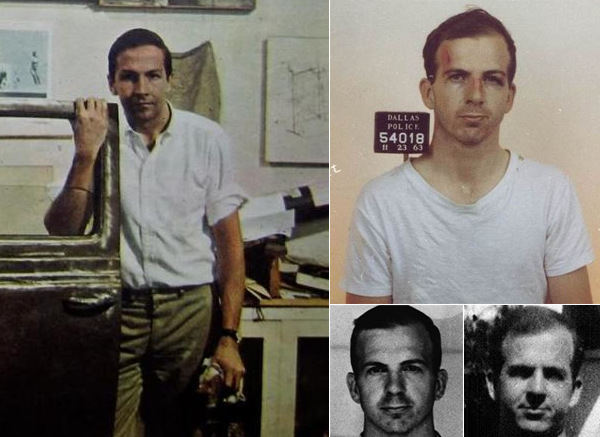

Erasing de Kennedy

On Saturday November 23, 1963, a day after John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Dallas Police took a mugshot of the alleged shooter Lee Harvey Oswald, who would himself be shot a day later and die. It is odd how the verb “shoot” is used to describe the act of firing a bullet at someone, taking a photograph of them, and as a substitution for “shit” when expressing frustration or dismay. A conspiracy theorist (or, Gore Vidal’s wonderful “conspiracy analyst”) would say that the acute shadows formed by Oswald’s face in the infamous rifle holding photo are not consistent with the other native shadows, an impulse which implicates painting’s long forgotten task of matching light and shadows — that the latter’s convincibility, the black weary shape it finds across a cheek, legitimized the former’s absoluteness, emitted by a candle, in a dark brown room somewhere, if we are to still believe those dark brown rectangles, hanging by wires on walls, dusty on the side that matters. In 1953, Robert Rauschenberg erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning solicited by the former for the sole purpose of doing so. De Kooning caved in, as his mind would also years later from Alzheimer’s, his slow fingers pinching at sculptures which — without commentary — looked like shit, like actual pieces of literal shit on a pedestal. A true misogynist, he called them women. Like their ghost pencil marks, you can kind of see the erased drawing behind Rauschenberg’s right shoulder, or not. It was an asshole art move, which are always the best to write about. But while art grasps for history, a man, or boy, can change the world with a gun. That the right to bear arms is only the Second Amendment is telling of what has always been on American minds, though countries born of bloodshed tend to continue that path. In 1964, Rauschenberg assimilated Kennedy, presumably around the time of the one-year anniversary of his assassination, into “Retroactive I” and “Retroactive II,” two near-identical paintings only distinguishable after some amount of concentration — the light variances of the silkscreens, the purposefully similar yet inextricably unique dabs of paint — visual signs depletive of meaning, an orgy of detached signifiers, the commentary of no commentary, which might have been his entire point, so sharp, silent, and unseen, like the tip of something shiny in the air, pulled to its target over time.

On nihilism

Williams College is a liberal arts college in Williamstown Massachusetts, from which Charles Webb, who wrote the novel from which Nichols’ The Graduate (1967) was adapted, graduated. He is oddly, or expectedly, not associated with the film’s success. He is married to Fred, who calls herself that name in solidarity with Fred, a support group for women with low self-esteem. His homeschooled children, now adults, sold their wedding presents back to their guests, each got divorced in protest against marriage, and now, rumor has it, work at kmart and live in a shack. “The Sounds of Silence,” (1965) enmeshed with the iconic pool scene, forty-six years after it was was released, would be performed by a visibly distraught Paul Simon at the 9/11 Anniversary Memorial Ceremony, wearing a suit of out respect but looking like he’s going in for a job interview. Benny is seduced by an older woman but falls in love with her daughter, played by one doe-eyed Katharine Ross, who seventeen years later would end up marrying Sam Elliott, the omniscient narrator of The Big Lebowski (1998), whose appearance as The Stranger at the film’s ending can be seen as a pedestrian second coming of sorts, which is an odd way for Marco Polo, or you, to wade across the chlorine to one Uli Kunkel (screen name “Karl Hungus,” who appeared in a porn film with Bunny) seen passed out next to empty Jack. I like it how, in bars or parties, a group of exclusively males standing in a circle will shoot straight whiskey or tequila — suddenly throwing their heads back as synchronized swimmers — followed each by a coy yet uncontainable grin, as if the word cool could not contain what had just happened. “Uli doesn’t care about anything. He’s a Nihilist,” soon-to-be 9-toe’d Bunny Lebowski says. “Ah, that must be exhausting,” goes The Dude, whose $0.69 personal check to Ralph’s for some milk in the opening scene was dated September 11, 1991, exactly 10 years before the event exactly 10 years before Simon’s sad song was sang again through the bravery of a non-facelifted face. As for that day, they said we were nihilists, so we said they were back. People talking without speaking.

American Apparent

In 1912, Egon Schiele was imprisoned for 3 days in a town outside of Vienna for producing hundreds of pornographic (according to the State) drawings discovered in his residence after he was arrested for soliciting an underaged girl to model nude for him. It is unclear if he had sex with his models, though it is commonly accepted as so. Painters and their models; writing professors and their students; rock musicians and their groupies. There is simply something gross about this. It is degrading for both sides. Of his models, one Valerie Neuzil (17 at the time), moved him to such a degree that he moved in with her, though ended up marrying Edith Harms, while maintaining his relationship with the former, who left him when she found out about the marriage, duh. Egon had his child in the latter, then died three days after she did, she six months pregnant, both (or all three) from the Spanish flu. His drawings are commended for their deft vigorous hand, but criticized by some for their empty stylization. A hardcover monograph of his work will run you $120.00 at a museum store, though a cunning curator may wish to simply decide on their favorite image and buy the postcard for $2.00. In 2008, American Apparel owner and creator Dov Charney allegedly opened the door in his boxers, removed his member from a “non-outsourced vertically integrated” flap, and forced Irene Morales, one of his models, exactly on her 18th birthday, to perform fellatio on him on her knees at the doorway, then forced her to repeat the act many times, “nearly suffocating her in the process,” according to the $250,000,000 lawsuit Morales filed in 2011. In his defense, Charney said “some people love sluts,” after leaking consensual text messages from Morales. Only evidence is evident, all else is merely apparent. Many other suits ended up as settlements, as many other suits ended up at used-clothing stores. Walk down the cool college-y street of your city towards the bauhaus-y designed store front, and you will see a group of headless manikins standing there. Their pose should be of repose, a calm loyalty that only those without a mind would not mind.

Workers in a Field

Jean-François Millet’s “The Gleaners” (1857) shows three peasant women gleaning a field after a harvest of crops, its depiction of the lower class most irksome to the French upper class, who didn’t want rural poverty and intimations of the 1848 French revolution in their Salon. I imagine artisanal cheese melting in their mouths and coursing straight to their hearts. Millet is just as known for “The Sower,” later copied by Van Gogh, and from which Simon & Schuster’s colophon is derived. Realism is used to describe Millet’s paintings, implying a kind of artistic integrity or moral clarity necessary for the unglamorous staunch view of the world; the problem is that Realism is also used to describe our later Renoir and Manet, whose pasty bourgeois subjects are safe from the sun under parasols and hands of shadows taught by the leaves above to protect the smiling faces. In fact, from the field to the park, the real R-word is Romantic, the aesthetically adroit projection of an ethos by which the lesser, us, learn to live. In 1999, three actors were allowed to do what they, likely with grim office jobs themselves in their past before said success, had, like us, fantasized doing. They were told to walk into a field subconsciously on the perimeter of an office building and destroy a fax machine with only their feet, fists, and one bat. They took turns with the bat, a phallic democracy both homoerotic and most American. Directer Mike Judge (Office Space, Beavis & Butthead), whose genius shall not be argued here, later added a Geto Boys song as an ironic, and mildly racist, “juxtaposition” to the whiteness of their white collar plight and excised rapture. When faceless bureaucracies are embodied by the broken means meant to convey them, it’s time to freak out. That a fax from afar is printed on recipient paper and not the sender’s is often forgotten, with people getting angry at the sender for being out of paper. The age of reason is now unreasonable. To come full circle is to start all over again, and I sometimes wonder if I’d be happier before the industrial revolution. I’d have strong arms, a nice tan, and no tweets to worry about. If the reader does not know where this is headed, may he or she be pointed outside, to workers in a field, whose very work seems futile but is somehow necessary in small unseen ways, from flax to fax, of horrible jobs existing for a reason, of civilization moving along slowly, before the sun sets, through near darkness and its nightly requiem of crickets, until it rises again.