Tunnel vision

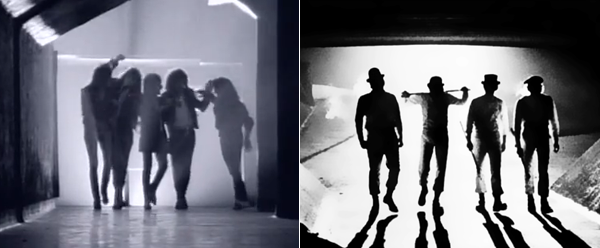

Hairband videos of the late-’80s seemed meta in how they “set up” the song by showing the band, usually conceitedly, approach the stage during the opening riff or drum beat, to kind of glorify, or prolong, the imminent explosion of the song (rap songs, similarly, often begin with vignettes of rappers speaking into the mic about how they are about to start rapping). Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer” (1986), whose titular contraction of “living” serves the lingo of our times, was in many ways the ultimate rock anthem video, with its talkbox riff, rigged flying theatrics, and artsy black & white lavender tint. I would “air band” it (an intricately spliced combination of air-guitar, -drums, -bass, and -vocals), running into furniture, discovering bruises the next day which unfairly implicated my parents. The song tells the story of Tommy and Gina, a young working-class couple whose love for each other compensates for their stout lives — while real life Ginas preferred displaying their mammalian buoyancies at the composer of the song, whose slo-mo moments right before the nipple highlighted videos of this nature. Of milk’s offering, newly satiated from Korova bar, we come across dystopian bros entering a tunnel in which they are to beat a homeless man to death. Anthony Burgess’s prophecy can now be seen on homeless beating videos, snuff meets Punk’d, in which teenage boys competitively break faces with cinder blocks and bats, the retina display of life perhaps more convincing than a video game. Misandry just happens. One may wonder if all videos are essentially games, life’s diorama inside a cartridge, the control pad’s rubber buttons as numb nipples whose virtual and distant volition is an actual child, silhouetted with his co-conspirators, in infamous anonymity.

Femme et al.

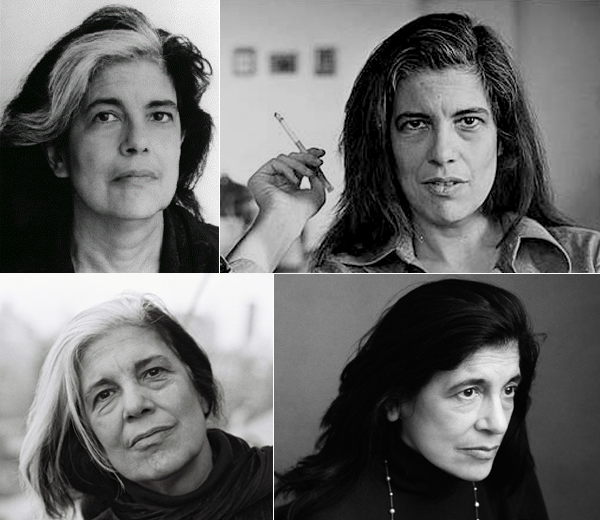

Pepé Le Pew was a French skunk (Looney Tunes, Warner Bros., 1945) who falls in love with a black cat whose backside and tail are accidentally painted white from a spilled bucket of paint. Thinking the cat is a skunk, “la belle femme skunk fatale,” Pepé courts her with obtuse conviction, the unwitting cat too docile to even meow. I’ve always found this cartoon bleaker than the rest, its lonely protagonist even more deluded than shotgun brandishing Elmer Fudd. Many earlier cartoons operate as grim allegories about futile pursuit (i.e. Woody Woodpecker, Tom and Jerry, etc.), as if already apologizing for adulthood. The false white stripe, then, may represent steadfast projection, however ingrown. This has little to do with Susan Sontag, other than, inversely, her admitting to dying her hair black once it went grey, save the streak of white for which she was known. Caused by Waardenburg syndrome — a rare genetic disorder characterized by pigmentation anomalies in minor cases, and deafness in more acute ones — the white streak became a signature of premature maturity, wisps that hinted, or rather could not contain, great wisdom. I use “admitted” in parallel to “disclosing,” which were Carl Edmund Rollyson and Lisa Olson Paddock’s word in Susan Sontag: The Making of an Icon (2000), as the implication is that the dyeing of one’s hair falls into the camp of cosmetic vanity, that she should have just “greyed out” the old fashioned way, to let the formidable stripe become unnoticeable with age. She is to die of cancer in 2004, which cynically brings to mind a statement of hers in the Paris Review (1967) that “the white race is the cancer of human history,” whose subsequently brilliant sarcastic recantation was that “it slandered cancer patients.” A great writer always wins on paper; as for real life, the loss is immeasurable. It’s endearing how bad white people feel, how you’ve turned your neutral description into a pejorative. I’ve decided to love her, regardless of her hair, on my behalf. It’s easier this way. If life is a game of leaving quotes behind, the dead always win. Now all of us have something to look forward to.

On Adoration

It is odd how someone so sly online can be so shy in real life. That the former must compensate for the latter is something many of us may relate to. As Amanda Bynes slowly goes insane, we have a new disaster to follow, eyeing the eye of the hurricane from the safe distance of a meteorologist in front of a green screen. I hadn’t even heard of her until some of her witty, curious, but ultimately desperate tweets (wanting Drake to “murder [her] vagina”; calling other female celebrities “ugly”; posting increasingly explicit selfies). I imagine a small stake through her cheek piercings, like shish-kebab, disrupting the flow of her tongue. As standard news outlets address this as “bizarre behavior” and “cries for help,” we enjoy the heightened narrative of non-fiction, though Bynes is as much a masterful creation as Madame Bovary herself. In what has now become #bynesing, Amanda shields her face in modesty, or horror, an eerie nod to the Islamic Burqa (or Niqāb, with a slit) featuring a little window through which women, in public and/or in front of adult males, can navigate their world with truncated periphery. This requirement, called “Hijab,” unsurprisingly stems from the Qur’an, a place of deep sexual paranoia, or subverted fantasies, regarding incest. It’s a mess, but basically, the hood somehow keeps slutty daughters from fucking their fathers or brothers. As one-fourth of the world’s population prays at five appointed times a day towards Mecca, it’s hard not to see such circadian devotion as a kind of ultimate militia come the apocalypse, whose semi-finals will likely be between Allah, Jesus, China, and Walmart.

Nymphomaniac

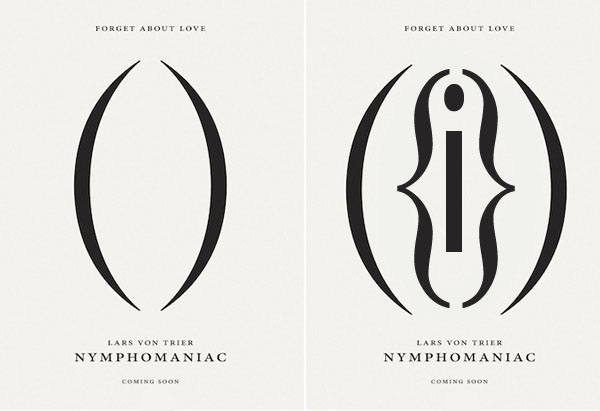

As we await Lars Von Trier’s Nymphomaniac, which seems like a sexual extension of Charlotte Gainsbourg’s character in Antichrist (2009), we are given — in the teaser poster — suggestive syntactical vulva by way of parentheses, which may bring to mind Seymour’s “bouquet of very early-blooming parentheses” in J.D. Salinger’s Seymour: An Introduction (1959). The impulse to render images using syntax turns <3 into a ♥, distilling language back into the Lascaux cave drawings, cuneiform, hieroglyphics, and early Chinese characters. Perhaps we want to move backwards, scratching images into dirt. A more meta interpretation of () might be the excised (implied) parenthetical note, though that is unlikely. This contributor, whose brief up-close encounters with female genitalia have been mostly with eyes closed, offers a more explicit rendering — the “i” perhaps hopeful first person, as in the first person to third base. If there is a douche in this enterprise, please apply your gaze at Lars himself, who seems obsessed with destroying the women in his films. Martyr is just a fancy way of saying mommy. His films are slow and gorgeous, into whose pretentiousness one simply caves. A common still shows Gainsbourg sandwiched between two black men as Oreo coitus. Shia LaBeouf’s in it, and you get to see his dong. The spectacle just wants eyes, not approval. I’ll see you in line.

Late work

One wonders if the staff of Dunder Mifflin ever saw the late Monet waterlilies painting, a print at least, framed in the conference room as a kind of covert bourgeois window through which one might mentally escape to softer times, whose chubby mascot was a man slowly taken by cataracts, whose artistic vision was no doubt clearer than his literal one. French impressionist (and, to a degree, Pop Art and Abstract Expressionist) prints are mainly used in corporate settings to placate the employee, condescendingly, as if all they needed to be happy was something pretty to stare at, when in fact it only implicates the dissonance between surrendered office life and the more vigorous ideals of artistic inquiry. I’ve always found the late Monet print an odd, yet provocative, choice. Perhaps the set designers wanted something deep behind the shallowness of Michael Scott. As The Office plays out its final season, we may be left with some more inadvertent metaphors: the casting politics of who would play the boss, and the legacy of an unstable company, who in a realist market would have been eaten alive by more faceless competitors Office Depot and Office Max; the sweet courtship and eventual nuptials of Jim and Pam, whose subsequent boredom of each other seemed to ooze from the actors without acting; the rogue zen of Stanley Hudson, who solved 10,000 crossword puzzles in what were likely out-of-body experiences; the increasingly comical scenarios less probable, obsolete after the novelty of the ironic “fourth wall nod” wore thin. Most compelling were the accurate personnel departments (e.g. Accounting, Office Relations, Sales, Human Resources, Executive, Warehouse, Production) ascribed to each character, whose demeanor and actions held consistent with them. Such vocational intricacy had, in the past with other shows, been simply consolidated as an abstract “job” to which someone went when they weren’t on the main stage, that is, home. The Office took the family away from home, into their own personal world of laughter and resent. Monet, the more successful of the French impressionists, built Giverny garden for the sole purpose of having a final chronic subject to paint until his death; he painted around two-hundred-and-fifty waterlilies, whose muddled canvases, thick and opaque, wore the transparent mask of a lake’s surface barely there. At its best, art is the profound realization of the invisible. Imagine a half-blind man — who famously declined ophthalmological help in aid of his abstractions — squeezing out more and more purple like an inside bruise finally surfacing, each work darker and darker, as if to trace the slow yet unwavering arc of an hourhand as it approaches night.

The Brothers Tsarnaev

While it may seem relevant that Chechnya is auspiciously sandwiched between Russia and the Middle East — exhuming the dormant winds of the Cold War, and the current conflict with Islamic extremism — the Tsarnaev brothers, regardless of how perceived their exile was, acted as Americans; that is, with a kind of free volition this country violently preserves. To simply call them assholes is somehow to dishonor their victims, many of them now amputees whose incomplete image in the mirror every morning will remind them forever of the blast, whose unexplained birth out of nowhere does well to implicate the universe itself. Time will tell how politically motivated this act was — though one doesn’t imagine our young Dzhokhar being the most cooperative, or coherent — hence categorized into either the ideological camp of Ted Kaczynski/Tim McVeigh, or the, sadly, more senseless camp of Columbine/Sandyhook, whose executors are getting younger and younger, and better armed.

While it may seem relevant that Chechnya is auspiciously sandwiched between Russia and the Middle East — exhuming the dormant winds of the Cold War, and the current conflict with Islamic extremism — the Tsarnaev brothers, regardless of how perceived their exile was, acted as Americans; that is, with a kind of free volition this country violently preserves. To simply call them assholes is somehow to dishonor their victims, many of them now amputees whose incomplete image in the mirror every morning will remind them forever of the blast, whose unexplained birth out of nowhere does well to implicate the universe itself. Time will tell how politically motivated this act was — though one doesn’t imagine our young Dzhokhar being the most cooperative, or coherent — hence categorized into either the ideological camp of Ted Kaczynski/Tim McVeigh, or the, sadly, more senseless camp of Columbine/Sandyhook, whose executors are getting younger and younger, and better armed.

David Remnick’s piece (from which this illustration and title is unabashedly taken) in the New Yorker is vulnerably sympathetic to the Tsarnaev family, a liberal impulse which is needed, should one brave the harsher waters of the more “patriotic” sentiment i.e. that we should just bomb “them,” whoever they are (just when you thought the postmodern “Other” was dead). That a white male has taken the throne of the Other may launch us into a new era. Not colored, or queer, or part of some thesis, mush less exotic, he is simply another one of the ever expanding “us” lost in the fold of America, whose race is ostensibly raceless, and whose nationality is a slow and steady reduction of endless immigrations. The idea is rather genius. A country for all, though it often seems like we’ve stopped earning this.

Not since the Revolutionary War — with the exception of Pearl Harbor and 9/11, both quickly mythologized, as if to eagerly render them irrelevant — has foreign conflict breached American soil. Truman’s Hiroshima and Bush’s Afghanistan were respective responses, the former’s flattening sadly more effective. War for us is cordoned off as an abstraction of what happens “over there,” bestowing the general populace a bloodless, though vehement, discourse about its many possible meaning(s) from behind televisions and computers. The Boston explosions simultaneously remind us of two somewhat contradictory things: that there will always be insane, strangely entitled, people (usually white men, or boys) who kill for no reason at all, pointing at in inward pathos; or, more formidably, that a spreading global war, whose disenfranchised have less and less to live for, can always permeate our borders. The easy allusions to Syria or Gaza, frankly, scare the shit out of me, and I think all of us. As for the Tsarnaev brothers (one notes the eerie invocation of the Karamozov brothers), their patricide may be indirectly directed at our founding fathers: brave, violent, and tired men, who likewise came to America to escape a troublesome place.

Presumptive Yet Likely Books

Brain Ramen and the Cattail Noose

by Haruki Murakami

Vintage, July 2013

345 pages / $22

One late afternoon, unemployed narcoleptic celibate Uno Moribundo, pensively awaiting the shipment of a real doll and some obscure jazz CDs, falls asleep in a large bowl of scalding ramen. Permanently disfigured with third-degree burns to his face, he wanders Tokyo’s underground wearing a Ringo Starr mask looking for blind children to bring home and love. With some weary repetitions, troublesome inconsistencies, and heavy-handedly overlapping plot points, it becomes apparent that Moribundo may be in a coma. “His pillowed brain resembled bloated ramen left in a bowl, the spilled broth grown tepid over the months as floor thought bubbles trying to remember something,” Murakami deftly writes. Enter Yoshi Yummimoto, a 14-year-old goth school girl whose Lorazepam habit may be seen as complicit auto-narcolepsy. She falls asleep in class, and on his face. Follow this unlikely pair through the mental labyrinths of memory, identity, intimacy, and self — to a climactic hot pot binge, which spilled, brings them to their knees.

April 16th, 2013 / 10:56 pm