Seth Oelbaum

Seth Oelbaum earned a poetry MFA from the University of Notre Dame. He is the founder of the Bambi Muse Tumblr and the author of macey [triolets], which was published by Birds of Lace.

Seth Oelbaum earned a poetry MFA from the University of Notre Dame. He is the founder of the Bambi Muse Tumblr and the author of macey [triolets], which was published by Birds of Lace.

I like chocolate chip cookie dough tons and I like death tons too.

Mary Jo Bang’s collection of poems, Elegy, doesn’t really touch on the former, but it does really touch on the latter.

The completely consuming force of death is illuminated in Mary Jo’s book. When someone asks her to define a day, Mary Jo replies: “Tragic from beginning to end.” As with a deft totalitarian leader, death is unceasingly omniscient: Mary Jo is covered in calamity.

There’s no timeout for Mary Jo. Some shut eye is shut down. In “Beneath the Din” Mary Jo reveals she’s in the “insomnia hour.” Later on, Mary Jo declares, “My ear is a beach / And the sea is talking to it incessantly.” Just as Heathcliff won’t let the Catherines be, death won’t stop his pursuit of Mary Jo. In “No Exit,” Mary Jo refers to her “tragic flawed fate going on and on and on.” It’s as if Mary Jo is a Victorian heroine and death is her boyfriend, who, though mean and rough, is still her one true love.

Death’s determination dismantles Mary Jo’s perception of time. The differentiation of months dissolve and what’s to come collies with the present. “A year in tatters is interrupted by the thought / That the future is manacled / To the indefatigable now of February,” says Mary Jo in “January Elegy.” It’s as if Mary Jo keeps her very own calendar. Death’s supplied her with a new system for marking time, which is what those bellicose, guillotine-inclined French Revolution boys did for a bit by altering the number of days in a week and renaming months.

In Ghostbusters II, the Marshmallow Man’s monstrous steps scatters all the New Yorkers in his path. In Mary Jo’s world, “every step is a dangerous taking.” The Marshmallow Man and death deliver destruction. Each movement is so scary to humans since each movement produces the possibility that humans and human things will be wrecked with impunity. The NYPD (who, unlike liberal New Yorkers, I like) couldn’t punish the Marshmallow Man and they can’t punish death.

So strong is death that non-human entities are scared of it too — even ghosts don’t try speaking to death about baseball or inviting it to tea: they simply “go blank” in its presence.

One of Mary Jo’s poems ends: “These birds eat and eat. Everything.” By birds, is Mary Jo speaking about death? It’s highly likely, since, as with the birds, death can tuck every single thing ever into its tummy.

Another poem of Mary Jo’s commences: “This was the drama / Of impossibility.” Throughout the collection there’s considerable references to performance, such as actors, screens, masks, and audience members. Since everything is performance (and everything really is a performance, so hush), death’s show is the best one, because death lasts forever, and in “Elegy,” Mary Jo spotlights the gargantuan ghastliness of death’s spectacle: “an intolerable end that keeps going on.”

World Series baseball is quite comely. The competition is carried out outside in the fall, so leaves are dying and falling off trees, it’s cold, and you get to start sporting layers, like multiple hoodies over a meaningful sweater over a button-down.

Moreover, baseball is slow, like an elderly person, and it’s quiet, like a deaf-mute. Both the elderly and deaf-mute are meritorious. The elderly are grumpy and crabby (as one should be), and deaf-mutes don’t talk and don’t hear, which is optimal, as there is very little that can be conveyed through talking and listening that can’t be conveyed much more marvelously through a poem, a story, or a Tumblr post

In “[The crowd at the ball game],” New Jersey boy William Carlos Williams compares the baseball setting to a totalitarian society, and that’s sensational.

This World Series is especially estimable because the St. Louis Cardinals are participating, and they feature many cute boys, like the hard-throwing closer, Trevor Rosenthal, and the tough as a truck catcher, Yadi.

Presently, the Cardinals and the meat-head East Coast liberals that some refer to as the Boston Red Sox have each won two games. If you haven’t been keeping up with all of the excitement then read Baby Marie-Antoinette’s recap of the first four games:

Last nighttime the St. Louis Cardinals beat the Boston Red Sox in game 2 of the World Series, and their triumph made Baby Marie-Antoinette less woeful than she was on Wednesday night when the Cardinals lost (which they’re not supposed to do).

As with Baby Marie-Antoinette, I think the St. Louis Cardinals should win the World Series, and I also would be fine if their commendable closer, Trevor Rosenthal, wanted to be my boyfriend.

But this post right here sort of tackles another topic.

Before the bottom of the 7th inning, the Boston Red Sox commemorated all of the people who were blown up in the Boston Marathon.

They came out onto the field, and James Taylor sang a song.

This instance illustrated a theme from one of my favorite books, Frames of War by Judith Butler.

In this book, Judith distinguishes between greivable lives, like the people on the Boston Red Sox’s field, and ungrievable lives, like the Muslim creatures who continue to be blown to bits.

Being a boy, I like violence. But I don’t like phoniness, and it seemed to me to be really phony for all of these Boston Red Sox people to portray themselves as empathetic and moral-loaded and whatever other terms they might throw out, when, really, they’re only empathetic and moral-loaded to those who subscribe to America’s depiction of a grievable life.

Since my mommy purchased me Laura Sims’s collection of poems, Practice, Restraint, I have read it more than five times.

The poems are small and tiny. They hardly take up any space (although they do take up some space, of course). The lines leave room for few words; some, like the commencing verses of “Bank Twenty-Seven,” only hold one or four:

Trees over here

Over there

In one empty classroom

The girl is turning

The town inside out

Such sparseness spotlights the empty white space, which I like; it’s as if the few words of Laura’s poems are speaking to the empty white space, acknowledging that the empty white space isn’t really empty white space, rather, there’s something in it, the way an abandoned house at the end of street isn’t really abandoned, since ghosts live there.

Many of these poems pertain to scariness. There’s empty classrooms, empty rooms in general, trees, dead things coming out of mountains, a house that shines, and a girl in marsh. Each of these listed things could contain ghastly properties.

In the empty classrooms there could be girls getting ready to launch a school shooting because they were teased for not being capable of applying makeup correctly.

The house that shines might be doing so due to a bright apparition that resides in there and effects itself each night when it causes some kind of chaos.

Violence is a part of the poems. Laura compares girls’ “shining eyes” to “shiny new bullets.” She also remarks, “so many / dead girls / in this shit-hole.”

Though girls aren’t boys, they can still carry out violence, like Valerie Solanas did, like Mary Tudor did, and like the Jawbreaker girls did.

Some, like former secretary of state Colin Powell, believe overwhelming force is the best way to be violent. Others, like insurgent Muslim boys, believe a tiny and almost hidden force is better. The sensibilities of Laura’s poems align with the latter; just because you’re not doing lots of things and taking up lots of space in plain sight doesn’t mean that you’re not powerful.

Last week, I published a tiny story by Baby Marie-Antoinette, one that was titled Gang Rape Me Now Please.

Then, last nighttime, while the world acted woeful (as usual), Baby Marie-Antoinette sent me a telegram, telling me that she had things to say to me.

When a girl who, at less than 42 months, already has a biopic starring the striking Kirsten Dunst wishes to say things to you, then obviously you heed that.

That’s what I did.

In a vintage skirt (because boys can clad themselves in skirts) and a St. Louis Cardinals sweater (because they’re the best baseball team ever, and the LA Dodgers are gay), I met Baby Marie-Antoinette (as well as her mommy) at a McDonald’s in Midtown.

Baby Marie-Antoinette munched on a vanilla ice cream cone. I did the same.

BMA (Baby Marie-Antoinette): Thank you very much for meeting me.

Me (M): You’re very welcome.

BMA: My mommy articulated that it’d be agreeable if I articulated further about gang rape and such, and I agreed.

M: K…

BMA: So… you should probably inquire further…

M: Why are you so struck by gang rape?

BMA: I don’t believe in autonomy, freedom of speech, freedom in general, liberty, individual rights, or any such stuff.

M: Why?

BMA: I am Catholic. I absolutely believe in God, as God will make it so that I am the Queen of France. God cares for me. Another girl who God cares for is Simone Weil. She is a French girl who is sort of looked down upon because she didn’t spend her nights at white people bars on the Lower East Side.

M: What does that mean?

BMA: She didn’t got nuts for the human body or anything that humans nowadays (or in the olden days) deem progress. In Simone’s notebooks, she states, “We possess nothing in this word other than the power to say ‘I.’ This is what we must yield up to God.” For Simone, all the rights that people are roaring for are abhorrent. They are as unheavenly as a croissant without warm cherry cream in the center. According to Simone, “The self is only a shadow projected by sin and errors which blocks God light.”

M: So even though America says the self is the splendidest form ever; really, it’s sordidness.

BMA: Uh-huh. So when the self is destroyed, and when the attributes attributed to selfhood are tossed into the trash, it’s not naughty for God, it’s naughty for the ideologies that promulgate free personhoods.

M: Like the United States of America.

BMA: That’s a country that’s corrupted by personhood. In Gravity and Grace, Simone says, “We have to be nothing in order to be in our right place.” But Americans advocate the antithesis. They try terribly hard to be something, which is why they talk so much, eat so much, spend so much, and make so much trash.

M: But really, this “something” isn’t “something”; really, this “something” is “nothing,” only a different kind of nothing than what Simone is referring to, as it’s a nothing that has nothing to do with God, and thus it’s meaningless.

BMA: Sigh.

M: So why does 24/7/365 gang rape stay on your mind?

BMA: Because with gang rape it’s boy after boy being utterly uncaring about your body and what you yourself want to do with it. Simone says in her notebooks, “The more I efface myself, the more God is present in the world.” I could try to terminate myself, but that seems so self-involved, so I’d rather have boys do it. According to Simone, “When the ‘I’ actually is abased, we know that we are not that.” I know that my body is not nice. A pink and fuzzy Miu Miu coat is nice. But flesh, like Simone says, is “vile.”

M: Maybe the reason why gang rape is regarded as one of the top revolting behaviors in the world is because so much of the world cares about their bodies and not about God.

BMA: Uh-huh, people nowadays seem to be invariably promoting themselves, especially on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and any other gay social media platform designed by California loser. Simone says, “There is a lack of grace with the proud man.” Does Sheryl Sandberg possess grace? No. She’d likely be really upset if boys gang-raped her.

M: But what about those who equate !@@$% with purity?

BMA: These types should read John Milton’s play, Comus.

M: I read that play while I ate a chocolate cupcake.

BMA: My mommy read it to me while I ate a raspberry cupcake.

M: It’s about a girl who’s lost in the woods and is danger of being raped by a monster.

BMA: But even if the monster did rape her, it couldn’t corrupt her, because her purity isn’t positioned in her skin.

M: Perchance this is why Baby George III says Sasha Grey is more religious than Adrienne Rich. Baby George III saw Ariana Reines’s lecture at NYU a while ago, and during the question and answer, she compared Jesus to porn starlets, since both are renown for being transfixed by myriad external elements.

BMA: Perchance… The reason why gang rape is regarded as it is is because the world is wrought with utterly unthinking ungracefulness.

This is when Baby Marie-Antoinette asked her mommy to purchase her another vanilla ice cream come.

A little bit ago, like a couple of nighttimes past or so, Baby Marie-Antoinette, the second Bambi Muse baby despot, sent me Gang Rape Me Now Please, a tiny story she composed.

A little bit ago, like a couple of nighttimes past or so, Baby Marie-Antoinette, the second Bambi Muse baby despot, sent me Gang Rape Me Now Please, a tiny story she composed.

She sent it through mail, not the kind that everybody today uses, but the kind that Lorine Niedecker and Louis Zukofsky used.

Being a boy, gang rape isn’t really applicable to me. So I sent the tiny story to a girl, or, to be more precise, a ghostly girl, as the girl was Helen Burns, Jane Eyre’s BFF.

Helen said that the tiny story unveils the utter unpleasantness of autonomy, consent, individuality, basic human rights, and so on.

Helen went on to say that Baby Marie-Antoinette’s story was much more Godly than America will ever be, and it’d be wonderful to share it, as 2013 earth needs God.

Heeding Helen’s counsel, here is Baby Marie-Antoinette’s tiny story, Gang Rape Me Now Please:

Once upon a time there was a French princess named Baby Marie-Antoinette.

Baby Marie-Antoinette liked mice, cherry cream cheese croissants, Disney princesses, and Christianity.

Baby Marie-Antoinette also liked boys.

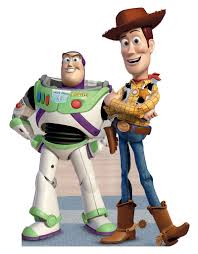

The boys in the Disney movies are heroic and dashing. They sail the seas (like Eric) and they save each other from impending doom (like Buzz Lightyear and Woody).

But the boys on 2013 earth were the opposite. They were nice, accommodating, and laid back. These average attributes caused Baby Marie-Antoinette to scream, “Ugh!”

One day Baby Marie-Antoinette was able to escape the clutches of her mommy, Empress Maria Theresa, and venture out into the Big Apple, searching for grandeur, extremeness, gang rape.

Baby Marie-Antoinette approached a bald boy with a big nose. She asked him if he’d gang rape her.

The boy declined, politely introduced himself (it turns out his name was Lloyd Blankfein), and asked Baby Marie-Antoinette if her mommy would be interested in purchasing some collateral debt obligations (CDOs).

Baby Marie-Antoinette shook her head. Then she approached another boy. The boy paired pink jeans with an ironic sweater. Baby Marie-Antoinette asked him if he’d gang rape her.

This boy declined as well, explaining that he was a feminist in the middle of shooting a Kickstarter-backed documentary about gender inequality.

Baby Marie-Antoinette sighed. Realizing that the chances of her meeting a big, bold, bullying boy were highly unlikely, she found her way back home, crawled under her Tinker Bell blanket, and cried.

Last nighttime I was in Lena Dunham Land, which I don’t like in the least, as 99 percent of the people who reside there claim to make poems, and these people who claim to make poems are nice, sociable, and happy. They would never use chemical weapons, nor would they ever vote to shut down the United States government, and all of that, to me, is utterly unacceptable.

But what’s very acceptable is Monica McClure. The poetess beauty (who, one day, will make a marvelous malicious housewife in Connecticut) hosted a party for her chapbook Mood Swing. In black tights and a Mandate of Heaven play suit, Monica read mean poems, harmful poems, and, since she’s a girl, poems about Diet Coke and makeup.

The edibles served at the reading included Skittles, which are yummy.

The reading was held at Berl’s Poetry Shop.

This, too, I approve of, as it permits one to purchase collections of poetry right away, such as Carina Finn’s Lemonworld, Chelsey Minnis’s Bad Bad, and certain ones authored by T.S. Eliot

Last nighttime, while trying to figure out if it’d be more appropriate to eat chocolate chip pancakes or cocoa pebbles for supper, my teddy bear Kmart sort of suddenly mentioned that there was a fair amount of occurrences in literature and perhaps I should tell of some of them.

Me: “Really?”

Kmart: “Uh-huh.”

Me: “K…”

On Sunday, Stephanie Berger will hold her first Poetry Brothel of the fall season. It’s at 102 Norfolk Street, starting at 8pm. The charming Irish boy editor of New Yorker Poetry, Paul Muldoon, will be there.

Yesterday, Carina Finn, for the first time in a rather long time, posted on her Tumblr, TH@SBRATTY. Her topic was the poetic life. “My life felt poetic only in the sense that hurt was the constant, and sadness, and want,” reveals Carina. “Not that I have been sad for forever, no one is, not even Hamlet, or Emily Dickinson.” Maybe so, but as long as they were on earth they were probably sad, as this place is filled with lunkheads who stare at screens 24/7/365.

Someone who is speaking about sadness as well is artist Bunny Rogers, who recently declared: “My depression is my commitment to drama. Viewing life as theatre creates a detachment that allows me to process an otherwise crushing environment of extremes.”

Though it is fall now, obviously, it used to be summer, and though summer is vulgar, this summer a relatable collection of poems and stories was published, meaning Gabby Bess’s Alone with Other People. This, too, is sad. One story is about a girl who “constructed herself as the modern tragic figure who would sacrifice herself for whatever.”

Unquestionably, the world is an utterly awful place, and it needs to go away fast.

While being educated upon literature, one of the most marvelous assignments I received was to conduct a close reading of a poem of my choosing. Though 99 percent of the people who associate themselves with literature nowadays probably perceive poems as mere documents that they’re coerced to comment upon in workshop, I am mesmerized by beatific poems, and I believe each one necessitates thoughtful evaluation. After all, when you see a beautiful look by, say, Calvin Klein, you shouldn’t just mumble “Nice job, Calvin” and then zip right along to the next one — that’s inconsideration. What everyone should do is concentrate on the look exclusively in order to notice the particular shade of grey and the way in which the squiggly white stripes contrast those of the grey ones.

The same should be so for a poem.

The poem I selected to do my close reading with was Charles Churchill’s night. An 18-century poet who didn’t like gay people, Charles is often ignored, while poets like putrid pragmatist Alexander Pope are emphasized. But, really, Charles needs ten times the heed of Alexander, as Charles is ten times as terrific as Alexander.

For Charles, the greater public views the daytime as the place of hardworking humans and the nighttime as the space of a sordid species. But in his poem, Night, Charles says that daytime is much more foul than nighttime. Using heroic couplets, Charles explains why the daytime is contemptuous, calling its denizens “slaves to business, bodies without soul.” In contrast to the spiritless stupids, those who wander in the night have an “active mind” and enjoy “a humble, happier state.” Near the end Charles states, “What calls us guilty, cannot make us so.” While I concur with Charles that just because the 99 percent say it’s true doesn’t make it true, I don’t agree that the nighttime is so wonderful, as gay people go out at night a ton, and gay people aren’t a thinking bunch.

But Charles’s poem is still bold, bellicose, and abrasive, and all of those traits are laudatory, and, through my close reading, I became much better acquainted with them.

Also disseminating a decided amount of close reading are the baby despots of Bambi Muse. Baby Adolf did one on Emily’s “Presentiment,” Baby Marie-Antoinette did one about Edna’s “Second Fig,” and Baby Joseph did one concerning William’s [“so much depends”].

Close readings appear to be very vogue. So, having already summed up a close reading of a boy poet, I will presently present a close reading of a girl poet.

On the day when al-Qaeda toppled the Twin Towers with commercial airplanes I was very upset, not because thousands of Americans had just died, but because the snack that my mommy always had in the car when she picked me up form school — a yummy, delicious, chocolaty, nutty, and creamy Snickers — had melted.

A lot of people seem to be very perturbed by 9/11, and these types are, according to me, phony, stupid, or both. What turns 9/11 into a tragedy isn’t that tons of humans beings die. Tons of humans beings die all of the time. Right now around 5,000 Syrians are dying per month, and only a tiny percentage of Americans seem to care enough to do anything. 9/11, though, is different because, as Noam Chomsky says, “For the first time, the guns have been directed the other way. That is a dramatic change.” Normally, America’s the country who gets to be grandly violent, like when Bill Clinton sundered a Sudanese pharmaceutical plant, decimating their medicine supplies, causing thousands to die from treatable diseases. But on 9/11 the opposite occurred. The country whose interests, according to Woodrow Wilson, “must march forward” got gashed. People — white people, Capitalist people, Western people — who weren’t supposed to die, died.

The controversial French boy, Jean Baudrillard, says that 9/11 made our “fantasies real.” All of those terrific and terrifying disaster movies — Independence Day, the Transformers, Schindler’s List — had tumbled into America’s tangible territory. The acts actually annihilated USA bodies. But just because Jean used the word “real” doesn’t make it so. For Jean, “reality only exists to the extent that we can intervene in it. But when something emerges that we cannot change in any way, even with the imagination, something that escapes all representation, then it simply expels us.” Just as I can’t kiss that cute Nazi boy in Schindler’s List, nobody was able to cease the Twin Towers’ collapse.