Interview Roundup Part Two: Trethewey, Price, Schutt, Gaudry, Glaser

.jpg) “What interests me most about poetry is the elegant envelope of form and the kind of density and compression that a poem demands. Because of those demands, I think I get to work more with silences than if I were writing prose. The silences are as big a part in my poems as what is being said. I believe my poems do a lot of work with what is implicit, rather than what is explicit. I just finished writing a work of creative nonfiction, Beyond Katrina, and I noticed that even in prose I have a strong tendency to circle back; repetition is a thing that I make use of constantly. It seems to me to be more natural in poetry and yet it also appears in my other writing.” – Natasha Trethewey, in Waccamaw

“What interests me most about poetry is the elegant envelope of form and the kind of density and compression that a poem demands. Because of those demands, I think I get to work more with silences than if I were writing prose. The silences are as big a part in my poems as what is being said. I believe my poems do a lot of work with what is implicit, rather than what is explicit. I just finished writing a work of creative nonfiction, Beyond Katrina, and I noticed that even in prose I have a strong tendency to circle back; repetition is a thing that I make use of constantly. It seems to me to be more natural in poetry and yet it also appears in my other writing.” – Natasha Trethewey, in Waccamaw

“No. I feel that my models came to me pretty early on, and it was who you mentioned—the early 20th century urban writers, like Richard Wright and Hubert Selby and Lenny Bruce—the language of Lenny Bruce. I like that rhythm, that high-speed, free-floating synaptic, anything comes out of your mouth, the acculturation, free-firing cultural riffs. Since then I sort of made my own way and made my own voice. I’ve read books that I admire, but nothing that made me, that taught me how to write.” – Richard Price, in Washington City Paper

“No. I feel that my models came to me pretty early on, and it was who you mentioned—the early 20th century urban writers, like Richard Wright and Hubert Selby and Lenny Bruce—the language of Lenny Bruce. I like that rhythm, that high-speed, free-floating synaptic, anything comes out of your mouth, the acculturation, free-firing cultural riffs. Since then I sort of made my own way and made my own voice. I’ve read books that I admire, but nothing that made me, that taught me how to write.” – Richard Price, in Washington City Paper

“At eighteen I began reading biographies of writers: where had they gone to school? Were they married, childless, published before age thirty? Were they mad, alcoholic, suicidal, dead at forty? I was not so unhappy growing up that I did not fear the loneliness that seemed to come with being a writer; many of my favorite writers had dispiriting lives, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to suffer if that is what it took, but I did want to write. Suffering comes in many different styles, of course; mine involved years of writing and rewriting paragraphs—typing, deleting, typing again and again before giving in to a watery glue of dialogue. (Writing dialogue most often makes me cringe. Recently, I discovered that verisimilitude or interest can be had in columns of dialogue if every other line is crossed out.) To be embarrassed by a story of one’s own making that dissolves after the first wrought gesture is one way of suffering.” – Christine Schutt, in Prime Number.

“At eighteen I began reading biographies of writers: where had they gone to school? Were they married, childless, published before age thirty? Were they mad, alcoholic, suicidal, dead at forty? I was not so unhappy growing up that I did not fear the loneliness that seemed to come with being a writer; many of my favorite writers had dispiriting lives, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to suffer if that is what it took, but I did want to write. Suffering comes in many different styles, of course; mine involved years of writing and rewriting paragraphs—typing, deleting, typing again and again before giving in to a watery glue of dialogue. (Writing dialogue most often makes me cringe. Recently, I discovered that verisimilitude or interest can be had in columns of dialogue if every other line is crossed out.) To be embarrassed by a story of one’s own making that dissolves after the first wrought gesture is one way of suffering.” – Christine Schutt, in Prime Number.

“Well, there was a time when I thought Richard Russo and John Irving (and Dickens) were gods — that long, overstuffed narrative exposition was entirely where it was at. I tried to write like those guys throughout my undergraduate and M.A. years. But then I graduated and discovered Blake Butler’s story in Ninth Letter, “The Gown from Mother’s Stomach,” went to his blog, discovered online writing, small presses, venues for innovative writing, writers like Millet and Bernheimer, discovered an entire world of publishing that didn’t give a hoot about the mainstream. I discovered a love of reading short, concise forms — flash fiction and prose poems. I hacked my previous writing to bits, culled the tightest, stand-alone sections, hacked away at them some more, and then suddenly I was publishing. These discoveries led to my breakthrough, surely.” – Molly Gaudry, in Hobart

“Well, there was a time when I thought Richard Russo and John Irving (and Dickens) were gods — that long, overstuffed narrative exposition was entirely where it was at. I tried to write like those guys throughout my undergraduate and M.A. years. But then I graduated and discovered Blake Butler’s story in Ninth Letter, “The Gown from Mother’s Stomach,” went to his blog, discovered online writing, small presses, venues for innovative writing, writers like Millet and Bernheimer, discovered an entire world of publishing that didn’t give a hoot about the mainstream. I discovered a love of reading short, concise forms — flash fiction and prose poems. I hacked my previous writing to bits, culled the tightest, stand-alone sections, hacked away at them some more, and then suddenly I was publishing. These discoveries led to my breakthrough, surely.” – Molly Gaudry, in Hobart

“Yes, the Pee On Water title has been troubling from before Adam Robinson. At my thesis defense, all three of my advisors advised me strongly against it. For a while, it seemed like people younger than 30 liked it, and people older than 30 did not. For a few weeks I tried to find a title to replace it, but I had been calling the bookPee On Water in my head from the time I first wrote that story, so it was a strong instinct to override.” – Rachel B. Glaser, in Rumble Magazine

On Fandom and Aliens Remaking the World

I am interested in the concept of fandom. Do you have a “fan” kind of relationship with the things you love? I feel like I have a very fan kind of relationship with the things I like, even if the people who make them are “nobodies” to society. I am a fan of random people, people who make beautiful things, people that have what I call the 6th sense—which is a special kind of perception, a special way of seeing or knowing. For example, Bhanu Kapil. I have a list of suspected “aliens”—passionate people that possess certain qualities. Bhanu is on it. Eileen Myles is on it too—I could listen to her talk all day because it’s always like wandering through a very fascinating and specific brain. I guess I don’t understand casual people—people that get enough sleep, people that are regular (as in consistent), people that find it easy to make new friends….

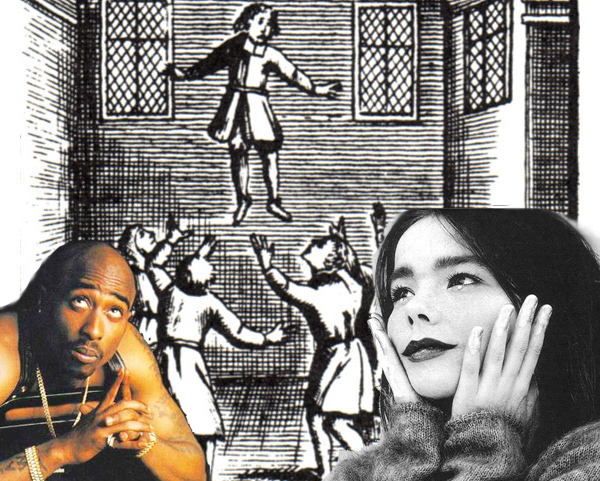

The epic poem that I wrote recently was about trying to find the lost aliens of planet earth, crisscrossing the country on foot in search of the other alien beings. Actually, most of the poem is about obsessively trying to escape through a crack in the sky until I am told by Tupac, who lives in the kingdom in the sky, that I should not try to ascend but should focus on my world—on “this worldliness.” That’s when I start trying to find the lost ones. I chose Tupac because my brothers and I were such big fans as children, and still to this day I think of him as a dynamic figure—tough and sensitive with radical and intellectual tendencies. So Tupac tells me I’ve got it all wrong. He encourages me to redirect my vision. I listened. I stumble upon a mysterious post office in Wyoming that has rows and rows of open postal boxes and I leave letters in the mailboxes knowing that the lost aliens of planet earth are the ones who will reply. We find each other and sing a note real loud and blast all of the beings that are ready to make the new world into the sky. As I am ascending Bjork is below me wearing a big dress while looking at me with tears in her eyes because she is so moved (I was a very big fan of Bjork growing up). One by one, we cross over into a crack that opens in the sky.

Interview Roundup Part One: Atwood, Abani, Bernheimer, Yoon, Lavender-Smith.

“So a lot of the things in my books are going to be your problems. They’re not my problems because I will be dead. So maybe I’m writing my books for you. That’s a scary thought, isn’t it?” – Margaret Atwood, in The National

“So a lot of the things in my books are going to be your problems. They’re not my problems because I will be dead. So maybe I’m writing my books for you. That’s a scary thought, isn’t it?” – Margaret Atwood, in The National

“It’s also important to say that I don’t write to find answers to anything—that’s just not the way I am, in my fictions and in my life. Questions don’t necessarily mean answers. It is more about seeing. Some kind of glimpse that helps me think about, say, why in peacetime American fighter planes dropped bombs on a Pacific island that was used by fishermen. Who those fishermen were, where they were from, who loved them, who they loved. Or why a man seems to grow more sad with his marriage and his own achievements in life as this island, his home, flourishes around him. These kinds of questions are endless, of course, and I think a part of me could have written about Solla forever. But I can now see the larger canvas of that place and the dark places aren’t so dark anymore.” – Paul Yoon, in The Rumpus

“It’s also important to say that I don’t write to find answers to anything—that’s just not the way I am, in my fictions and in my life. Questions don’t necessarily mean answers. It is more about seeing. Some kind of glimpse that helps me think about, say, why in peacetime American fighter planes dropped bombs on a Pacific island that was used by fishermen. Who those fishermen were, where they were from, who loved them, who they loved. Or why a man seems to grow more sad with his marriage and his own achievements in life as this island, his home, flourishes around him. These kinds of questions are endless, of course, and I think a part of me could have written about Solla forever. But I can now see the larger canvas of that place and the dark places aren’t so dark anymore.” – Paul Yoon, in The Rumpus

“I truly believe that writing is a continuum—so the different genres and forms are simply stops along the same continuum. Different ideas that need to be expressed sometimes require different forms for the ideas to float better. I don’t write essays as often as I should.” – Chris Abani, at Utne Reader

“I truly believe that writing is a continuum—so the different genres and forms are simply stops along the same continuum. Different ideas that need to be expressed sometimes require different forms for the ideas to float better. I don’t write essays as often as I should.” – Chris Abani, at Utne Reader

“I think, as Nabokov did, that ‘all great novels are great fairy tales,’ and then some. If you show me a book – a novel, a story collection, a collection of poems, a series of one-act plays, a screenplay – in any style from mainstream to experimental – I will show you the fairy tales in it. I can find not only the influence of fairy tales, but how fairy tales have given the narrative shape.” – Kate Bernheimer, in Room 220

“I think, as Nabokov did, that ‘all great novels are great fairy tales,’ and then some. If you show me a book – a novel, a story collection, a collection of poems, a series of one-act plays, a screenplay – in any style from mainstream to experimental – I will show you the fairy tales in it. I can find not only the influence of fairy tales, but how fairy tales have given the narrative shape.” – Kate Bernheimer, in Room 220

“First, it’s hard for me to say that I ‘expect’ a reader to do anything. (Although the book does posit an imaginary reader, a construction which seems to issue from my neuroses.) But I believe there are a number of things a reader might do with entries such as those: she might be compelled to project a narrative from the fragment; she might be compelled to gather these fragments so to project an intellectual persona for their author; or she might be compelled to mine these fragments for clues, for something like the shadows of a narrative that isn’t explicitly presented by the book, a narrative whose protagonist is named Evan Lavender-Smith. Or she might perform some combination of these three operations. Or she might slam the book closed. In any case, part of my intention in constructing a book out of a seemingly haphazard collection of notes was that these notes, by virtue of their accumulation and juxtaposition and patternation, would end up working overtime (not unlike what we might expect of the bits and pieces of a conceptual art). The tenor of that extra work would, ideally, be unnameable, too complex to pin down; just as the tenor of great allegorical writing constantly eludes the grasp of full understanding and interpretation.” – Evan Lavender-Smith, in The Faster Times

“First, it’s hard for me to say that I ‘expect’ a reader to do anything. (Although the book does posit an imaginary reader, a construction which seems to issue from my neuroses.) But I believe there are a number of things a reader might do with entries such as those: she might be compelled to project a narrative from the fragment; she might be compelled to gather these fragments so to project an intellectual persona for their author; or she might be compelled to mine these fragments for clues, for something like the shadows of a narrative that isn’t explicitly presented by the book, a narrative whose protagonist is named Evan Lavender-Smith. Or she might perform some combination of these three operations. Or she might slam the book closed. In any case, part of my intention in constructing a book out of a seemingly haphazard collection of notes was that these notes, by virtue of their accumulation and juxtaposition and patternation, would end up working overtime (not unlike what we might expect of the bits and pieces of a conceptual art). The tenor of that extra work would, ideally, be unnameable, too complex to pin down; just as the tenor of great allegorical writing constantly eludes the grasp of full understanding and interpretation.” – Evan Lavender-Smith, in The Faster Times

What is Experimental Literature? {Five Questions: Debra Di Blasi}

Debra Di Blasi (www.debradiblasi.com) is founding publisher of Jaded Ibis Press and president of Jaded Ibis Productions. In addition to her publishing role, she is a multi-genre writer and artist whose books include The Jirí Chronicles & Other Fictions; Drought & Say What You Like; Prayers of an Accidental Nature; What the Body Requires, and Skin of the Sun (forthcoming). Awards include a James C. McCormick Fellowship in Fiction from the Christopher Isherwood Foundation, Thorpe Menn Book Award, Cinovation Screenwriting Award, and Diagram Innovative Fiction Award. She teaches and lectures on 21st Century narrative forms.

Rebecca Solnit on a Deficit of Language

I’m a writer, so I spend a lot of time alone at home, but I also spend a lot of time as an activist in the streets, in gatherings and things like that, and following revolutions around the world: the Velvet Revolution, Tiananmen Square, the Zapatistas … In those moments, I’ve discovered in myself and in others a deep happiness, an unknown desire that’s finally fulfilled to be purposeful, to be a part of history and society, to have a voice.

One of my arguments in A Paradise Built in Hell is that we have almost too much language for private needs and desires and not nearly enough for these other things. This need and desire is so profound that when it’s fulfilled, you find these weird moments of joy despite everything in disaster. The whole world is falling apart, but I am who I was meant to be: a citizen, a rescuer, a resourceful person who belongs to and is serving a community.

The Spirit-Bone of Water

Wilson Harris

In this 2003 interview with Fred D’Aguiar, Wilson Harris speaks of place as character:

FD’A: A great magical web born of the music of the elements is how one may respond perhaps to a detailed map of Guyana seen rotating in space with its numerous etched rivers, numerous lines and tributaries, interior rivers, coastal rivers, the arteries of God’s spider. Guyana is derived from an Amerindian root word, which means “land of waters.” The spirit-bone of water that sings in the dense, interior rain forests is as invaluable a resource in the coastal savannahs which have long been subject to drought as to floodwaters that stretched like a sea from coastal river to coastal river yet remained unharnessed and wasted; subject also to the rapacity of moneylenders, miserable loans, inflated interest. READ MORE >

Doing the Things You Ain’t Sposed To Do

J. Robert Lennon’s Ward Six blog has something interesting at least twice a week. The latest post, “Forbidden things you can do anyway,” concerns:

an amusing exchange with a friend on facebook, a fellow teacher, who presently is grappling with inexperienced writers’ mistakes. She has been citing the mistakes, and then I have been firing back with examples of really good fiction that uses the “mistake” to greater ends. For instance, to “it was all a dream” I countered David Foster Wallace’s “Oblivion.” “Everyone dies in a car accident at the end” reminded me of Charles Baxter’s “Saul And Patsy Are Getting Comfortable In Michigan” (although he did bring them back to life in a later story and novel). And when my friend complained that her students don’t even know to start a new paragraph for dialogue from a new speaker, I threw down Stephen Dixon’s Interstate.

Reading it put me in mind of a beloved former teacher who intentionally pushed everyone’s dare-me buttons by passing out a list of twenty declarations about writing he called “The Rules” at the beginning of every new class, and no one ever seemed to notice amidst the grousing that Rule #20 was: You can do anything you want, so long as you can get away with it, or that none of his own stories strictly followed the prescriptive regime The Rules would imply.

This week in one of my classes, a student turned in a story that began: Here I am, facing the blank page, and someone said: You can’t do that. But I was thinking of the second paragraph of E. L. Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel, which goes like this:

This week in one of my classes, a student turned in a story that began: Here I am, facing the blank page, and someone said: You can’t do that. But I was thinking of the second paragraph of E. L. Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel, which goes like this:

This is a Thinline felt tip market, black. This is Composition Notebook 79C made in the U.S.A. by Long Island Paper Products, Inc. This Daniel trying one of the dark coves of the Browning Room. Books for browsing are on the shelves. I sit at a table with a floor lamp at my shoulder. Outside this paneled room with its book-lined alcoves is the Periodical Room. The Periodical Room is filled with newspapers on sticks, magazines from round the world, and the droppings of learned societies. Down the hall is the Main Reading Room and the entrance to the stacks. On the floors above are the special collections of the various school libraries including the Library School Library. Downstairs there is even a branch of the Public Library. I feel encouraged to go on.

A young woman I know once wrote a beautiful story from the point of view of a wine glass that sat in a room where a pair of lovers were ruining themselves. READ MORE >

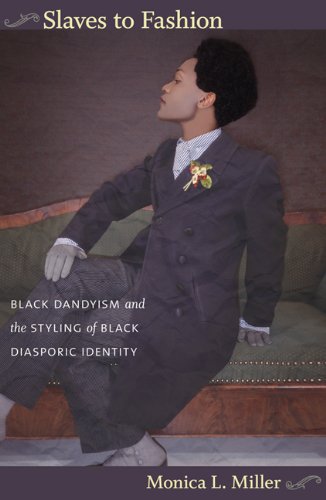

Miller, Monica. Slaves to Fashion (2009)

Slaves to Fashion is a pioneering cultural history of the black dandy, from his emergence in Enlightenment England to his contemporary incarnations in the cosmopolitan art worlds of London and New York. It is populated by sartorial impresarios such as Julius Soubise, a freed slave who sometimes wore diamond-buckled, red-heeled shoes as he circulated through the social scene of eighteenth-century London, and Yinka Shonibare, a prominent Afro-British artist who not only styles himself as a fop but also creates ironic commentaries on black dandyism in his work. Interpreting performances and representations of black dandyism in particular cultural settings and literary and visual texts, Monica L. Miller emphasizes the importance of sartorial style to black identity formation in the Atlantic diaspora.

The Pale King Changes

Today at Conversational Reading, Scott Esposito linked to a Google document that showed differences between the recent David Foster Wallace excerpt in The New Yorker titled “Backbone” and a transcription of Wallace reading the same piece in 2000, what Wallace then called ‘a fragment of a longer thing.’

Esposito writes:

It’s common knowledge now that Wallace did not get close to finishing The Pale King, and that the book that will be published on April 15 represents a heavily edited and stitched together version of what Wallace left behind. Clearly, this book has been made to serve the many readers out there who would like to see a completed, standardized version of The Pale King.

For more, go to the full post.

School of Hard Knocks

There is a lot of talk about the MFA, pro and con, and a corresponding vilification or romanticization of the autodidact who goes it alone and succeeds. As a writer, I’m glad I’m better because I got one. As a reader, I say: Who cares whether the writer did or didn’t get one? All that matters is whether or not what’s on the page knocks me out.

My buddy Frank Bill went it alone, and he’s doing pretty well these days. Soon FSG will publish his short story collection Crimes in Southern Indiana and his novel Donnybrook. They’re gritty stories that might put you in mind of Larry Brown or Donald Ray Pollock or Bonnie Jo Campbell. Today he posted a brief synopsis of the hard road from there to here. It is full of long hours reading and writing and stuff like this:

I gave up my studies in Chinese martial arts to write. I lost two grandparents. My dog died. My wife lost both of her grandparents within six months. My mother was diagnosed with an incurable cancer. She went through a second divorce. I went from 14 years on night shift to day work. The economy went to shit.

Reading it, I thought: Here is a guy who works harder than any seven human beings. That’s no guarantee that you’ll ever find readers, but that plus some talent plus having something to say plus the ability to be like a small child who will never take no for an answer plus some good luck might do the trick. Now the good luck is the reader’s. I can’t wait for his books to come into print, so I can buy copies for everyone I know. Here’s a link to his blog post.