First Sentences or Paragraphs #5: Best European Fiction 2010 Edition

[series note: This post is the fifth of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

“Albania is a country where no one ever dies.”

– from The Country Where No One Ever Dies, Ornela Vorpsi

“If I had urinated immediately after breakfast, the mob would never have burnt down the orphanage.”

– “The Orphan and the Mob,” Julian Gough

“A cousin of mine had an aquarium built on her terrace, a rather imposing tank where strange, exotic sea creatures amused themselves in the company of all sorts of local specimen, destined to be eaten.”

– from While Sleeping, Antonio Fian READ MORE >

First Sentences or Paragraphs #4: Norton Anthology of Short Fiction A-G Edition

[series note: This post is the fourth of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

“The slaughter hasn’t started yet.”

– Lee K. Abbott, “One of Star Wars, One of Doom”

“That was the year Hunca Bubba changed his name.”

– Toni Cade Bambara, “Gorilla, My Love”

“What he first noticed about Detroit and therefore America was the smell.”

– Charles Baxter, “The Disappeared”

“Alberto Perera, librarian, granted no credibility to police profiles of dangerous persons.”

– Gina Berriault, “Who Is It Can Tell Me Who I Am?”

“A man stood upon a railroad bridge in Northern Alabama, looking down into swift waters twenty feet below.”

– Ambrose Bierce, “An Occurence at Owl Creek Bridge”

“The visible work left by this novelist is easily and briefly enumerated.”

– Jorge Luis Borges, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” READ MORE >

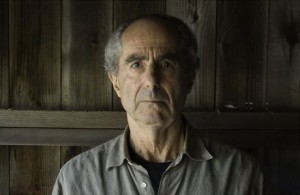

First Sentences or Paragraphs #3: Philip Roth Edition

[series note: This post is the third of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

The first time I saw Brenda she asked me to hold her glasses.

– Goodbye, Columbus

Dear Gabe, The drugs help me bend my fingers around a pen. READ MORE >

First Sentences or Paragraphs #2: Big Novel Edition

[series note: This post is the second of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

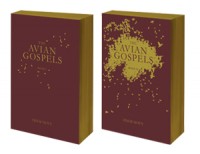

“Our God surpasses the Gypsy god; He is more avuncular and noble, though some of us begrudgingly admit their god is more assertive than our God, whom we haven’t seen or heard from since He rose from His own corpse and promised to rescue us from peril, and He has, though in secret, and if you could witness His wondrous methods you surely would fizzle in awe, so decent and grand is He, our Savior, who speaks in a voice that is no voice, not the song of any bird, not the snap of burning logs or crunch of shoes on sand.”

– The Avian Gospels, Adam Novy

“This book is largely concerned with Hobbits, and from its pages a reader may discover much of their character and a little of their history.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, J.R.R. Tolkien READ MORE >

First Sentences or Paragraphs #1: Mary Miller Edition

[series note: This post is the first of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ll be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

There’s a leak, I told him, it’s right over my bed. He didn’t believe me. I was a girl.

– “Leak”

My sister is inside watching a movie and bleeding. I don’t bleed anymore. It’s not something I thought I’d miss.

– “Even the Interstate is Pretty”

He had an air gun, a beer box set up to shoot. We were in a hotel room in Pigeon Forge. READ MORE >

Seminar in Getting Quickly to the Trouble: First Sentences from Christine Schutt’s Nightwork

1. She brought him what she had promised, and they did it in his car, on the top floor of the car park, looking down onto the black flat roofs of buildings, and she said, or thought she said, “I like your skin,” when what she really liked was the color of her father’s skin, the mottled white of his arms and the clay color at the roots of the hairs along his arms.

1. She brought him what she had promised, and they did it in his car, on the top floor of the car park, looking down onto the black flat roofs of buildings, and she said, or thought she said, “I like your skin,” when what she really liked was the color of her father’s skin, the mottled white of his arms and the clay color at the roots of the hairs along his arms.

2. I once saw a man hook a walking stick around a woman’s neck.

3. She was out of practice, and he wanted practice, so they started kissing each other, and they called it practicing, this kissing that occused him.

4. I date an old man, a man so old, I am afraid to see what he is like under his clothes. READ MORE >

Favorite First Sentences

Alright. All this Lish talk has me thinking about first sentences: the pleasure derived from them, the importance, the world-containing, etc.

My favorite first sentence is from Blood Meridian, which is weird to me because I’ve tried to read the book three times and have put it down halfway each time, but it is still a powerful book, maybe too powerful for me at the moment. Anyway, its first sentence:

See the child.

That, to me, is awesome; a plain evocation, and commandment, biblical as all hell which is what Cormac does so wonderfully.

And my other favorite opener, from The Stranger:

Maman died today.

Detached, even with the endearing colloquialism. Prescient, full of doom.

Alright, now you go.