A List of Especially Memorable Fiction and Nonfiction from 2016

For the past few years I’ve been keeping a list of all the books I’ve read. This simple trick has resulted in a marked increase in the amount of reading I do. I group the book titles by month; when the date is getting to be in the mid- to late 20s and I check my list to find that I’ve only listed one or two books so far, which is often the case, the next several days will include harried bouts of late-night reading intended to prevent myself from later feeling ashamed when I would hope to be proudly perusing my list.

Highlights from this year’s list follow the jump. READ MORE >

An Interview with Gabriel Blackwell

I interviewed Gabriel Blackwell this weekend. We talked about his new book, The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised-Men: The Last Letter of H.P. Lovecraft, which is a strange, scary, and above all absorbing novel about the final days of said author of the weird. We talked about our experiences with Lovecraft and Lovecraft fanfiction, Mexican men’s shelters, why we don’t like House of Leaves, and writing “objectively,” among other things. Please watch and enjoy. Then buy his books.

Video Review of The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting Improvised Men by Gabriel Blackwell

Trays of live worms for consumption, a nightly stroll with the shells of dead animals, and an arm covered in yogurt and soy sauce that smelled like strawberry grease for a whole afternoon; these are the ingredients for this new video book review of Gabriel Blackwell’s book by Gabriel Blackwell and meta-Gabriel Blackwell from CCM. I don’t know which of them is real. I think I’ve been hypnotized by Joseph Michael Owens’ music tracks. But I didn’t make this video. My wife did. She says she’s never seen any of the footage included and doesn’t understand why I’m crediting her. I don’t like strawberry soy sauce covering my arm so that my hands are unctuously melting into my chest. I’ve never eaten living worms before. I need to go back to America and have cheeseburgers made of artificial cheese and meat so I can have a culinary epiphany and shit out truths inspired by film cuts of scatological epics. You should read The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men from CCM by Gabriel Blackwell reviewed by Peter Tieryas Liu and Angela Xu with music from Joseph Michael Owens and edited by Janice Lee.

(Read the previous review on HTMLGIANT here)

November 7th, 2013 / 11:49 am

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men by Gabriel Blackwell

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men

by Gabriel Blackwell

Civil Coping Mechanisms, Available October 2013

Gabriel Blackwell channels H.P. Lovecraft in The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men, an epistolary metafiction that serves as part of a trilogy of works connected by his earlier Shadow Man and Critique of Pure Reason. In the introduction, Blackwell reveals that he has set out to Providence, Rhode Island, to find his girlfriend, Jessica, who disappeared while he was finishing the writing of Shadow Man. During that trek to Providence, he discovers the final letter of H.P. Lovecraft and that last message comprises most of the book in a footnoted poioumena intertwining his own desperate search with Lovecraft’s pestilential descent into madness. This isn’t just a pastiche of Lovecraft though, who died of intestinal cancer and whose last years were the most painfully productive. The mystery takes on a bizarre twist when he discovers the letter is addressed to another Gabriel Blackwell. Horror gets deconstructed and Lovecraft is retrofitted in a work that is less concerned with categorization than the ‘dissolution’ of existence. Experience itself becomes suspect as does the scholarship of pain. Blackwell, the meta character in the book versus the actual author, is typing out Lovecraft’s final letter. But as he does so, he is faced with a troubling revelation:

“That is, coming to the end of the particular sentence I was typing, I would look back over its analogue in the letter and would be unable to find even a third of what I had typed… This was undoubtedly made worse by the thicket of Lovecraft’s characters, by their lack of line breaks and paragraph breaks and even space between words, but it was also a quality of the prose. The events I was transcribing had not only not happened in life but not happened in the letter, either.”

It’s a setup for a mystery, a noir doused in elements of phantasmagoria with a magical lantern projecting Blackwell’s prose. The events described within are as gruesome and macabre as a Lovecraft story and in fact could be mistaken for one of his short stories. Horrible things are happening to the people in Lovecraft’s vicinity as in “this disgusting pile” that “was the remains of a man after he had been devoured and regurgitated by some horrid fungus or slime mold!” The grippe in his belly is devouring him from within and his mental state is corrupted into a decay and darkness that overwhelms his vision as much as his being:

“This thing in the basement was some sort of central node, a convergence of nerves. It was dowered with dark properties and obedient to dark laws; darkness was its element as air is the cloud’s, as water is the sea’s- the clashing, gnashing plates of its existence, in all of their horrifying splendor, were not so much dark as in aspect as of the dark…”

What adds a twist and requires a philological scalpel are the footnotes Blackwell uses to annotate his transcription of the letter. Much of the notes involves further elaboration of the plot details he outlines in his introduction. But there are disturbing intimations that require deciphering, a linguistic sonar to extrapolate from the echoes of meta-Blackwell’s journey. As his pursuit of Jessica becomes more desperate, his physical plight degenerates in a downward progression similar to Lovecraft’s. He is starving, cold, and suffering anemia. His body gets soaked with ink to the point where he does not recognize himself. With his impoverishment, things only get worse:

“I had a chronic inflammation around my anus- it itched all of the time and stung like a cut doused with hydrogen peroxide when wetted. I worried that I had soiled myself because of the wetness there, but always it was only blood.”

August 12th, 2013 / 11:00 am

“Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer,” edited by Gabriel Blackwell

Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer

Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer

Edited by Gabriel Blackwell

Civil Coping Mechanisms, October 2012

286 pages / $13.95 Buy from Civil Coping Mechanisms or Amazon

Is there a form called smart noir? There should be. In Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer, published by Civil Coping Mechanisms, Gabriel Blackwell both conducts and writes the story. As the meta-writer and the meta-detective, he’s inside what happens, and outside, all at the same time. Blackwell claims, rather coyly, to be the “editor” of Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer, and he is listed as such on the cover. But like a savvy gumshoe, Blackwell is too humble—and too sneaky—to list his skills upfront. His project is to blur lines between fiction and nonfiction; genre and form; noir and innovation.

We should consider ourselves forewarned meta-readers because Blackwell, as editor of this book, as author and researcher, is the ultimate shadow man. Blackwell disappears into the story and lets us know that he will be seen—and not seen:

We read to name that “pink elephant” in the room and, in the manner of noir, to find that missing femme fatale in the bar. The reader’s suspicious impulse might be to sit with the book and with Google, to search what is fiction, nonfiction, or imagination. We are inside the story as it unravels and outside the story as it is revealed. The story becomes confounding, like “a maze”:

I soon gave up the inter-textual Google approach to reading Blackwell and let myself be drawn into the cheeky editor’s devilish and impish fun. Those who are unseen and unknown are often the characters of literature that might reveal the most, were we to bother to ask. Blackwell bothers. He uses this knowledge, his questions, to great effect, illuminating a man who existed and didn’t exist, someone who disappeared with nary a backward glance.

February 15th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Weston Cutter interviews Gabriel Blackwell

I’m a huge admirer of Gabriel Blackwell — as prose editor at Noemi Press, I’m publishing his book of short fiction Critique of Pure Reason very soon, and I’ve published a piece of his body of work in almost every venue I’ve gotten my hands on. What I mean to say is that I can vouch for him as a writer and as a human being, and that you should also check out his novel Shadow Man, about which Weston Cutter has interviewed him. Here is Weston’s introduction, and their interview:

I’m a huge admirer of Gabriel Blackwell — as prose editor at Noemi Press, I’m publishing his book of short fiction Critique of Pure Reason very soon, and I’ve published a piece of his body of work in almost every venue I’ve gotten my hands on. What I mean to say is that I can vouch for him as a writer and as a human being, and that you should also check out his novel Shadow Man, about which Weston Cutter has interviewed him. Here is Weston’s introduction, and their interview:

Gabriel Blackwell’s Shadow Man: a Biography of Lewis Miles Archer arrived in black and white. I mean that both the galley copy was not full color, and that the book offers itself as a thing in or amidst a noirish fog, like some old cinematic masterpiece. Here’s how it starts: “Lewis Miles Archer, or anyhow the man known to creditors and clients as Lewis Miles Archer for just long enough to build up a respectable sheet of both, was born sometime between 1879 and 1888, somewhere in the shadow of Lake Michigan.” What Blackwell’s doing with this sort of dancing-away imprecision (four different states, for instance, could claim regions in the shadow of Lake Michigan) is crafting a slippery-but-detailed-as-possible biography of a fictional character. What actually happens to you as you read is you feel the line between ‘real’ and ‘fiction’ slipping, twisting and going porous in ways that, at least to this reader, become unsettling in fantastic ways: one less reads Shadow Man than goes into it and, later, comes out from it. It’s a hell of a thing. Gabe and I recently batted a single round of questions back and forth, hoping we’d get into more questions but then, after the first round, realizing 1) we’d gotten done what we’d hoped and 2) life intrudes.

Weston Cutter: Were there any rules in how you composed this book? In other words, did you keep 100% fidelity to the fictiveness of fiction and the ‘reality’ of reality? And how did this book end up taking the form it did? I guess mostly this question’s one rooted in fascination, one writer to another saying: how the fuck did you even find the trail that let you even begin to walk toward the result that is this book? How does one do that?

Gabriel Blackwell: I don’t think I thought of them as rules, but I guess they could be viewed that way—I created none of my characters and tried as much as possible to put the events from my texts (Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, and Ross Macdonald’s The Moving Target) into new contexts rather than invent other events to suit the narrative. But those didn’t seem like rules—I was just trying to write a book that worked in the way that I wanted this book to work. Shadow Man, which has to do with inheritance and imitation, needed to be a node rather than a terminal, a book that pointed outside of itself in constructive ways. I like lots of terminal fictions, books that assert that what they are describing is to be believed for the duration of their story and no further, books that begin and end inside the author’s head. But it’s rare that I’m actually caught up in those books; I’m always conscious of the writer playing house with me. That tends to take me out of it. I don’t want to read a transcript of someone playing with paper dolls, not if it isn’t really compelling. READ MORE >

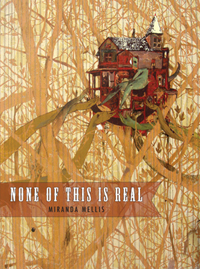

None of This Is Real

None of This Is Real

None of This Is Real

by Miranda Mellis

Sidebrow, April, 2012

115 pages / $18 Buy from Sidebrow or SPD

O, the subject of the title story of Miranda Mellis’s collection of short and long fiction, None of This Is Real, seeks solace (he has headaches—better to say “pain management,” then? we’ll see) in something called “Path to a Position™,” purveyed by its shadowy practitioner, Tiara Scuro: “She outlined for O the steps by which he would, with her, find his position. . . The old school believed the antidote for despair was courage, she said, but the real anti to the dote is a comforting distortion; this is what I call somatic realism.” “Somatic” realism? Is there another kind? Or do we deal in phenomenology?

“For years I had been removing the ground from under my clients,” she tells him,

April 23rd, 2012 / 12:00 pm

This New and Poisonous Air by Adam McOmber

by Adam McOmber

BOA Editions, 2011

180 pages / $14 Buy from BOA Editions

Imagine, behind glass or roped off from strangers, a representative sample of your wardrobe, adorning a dummy or hung flat and mummified; perhaps beside it, a selection of your tools—laptop, remote, cell phone; your furniture—the bed you sleep in, the chair you sometimes recline in, the coffee table your ankles once rested on. Your imprint is bound to be very slight on this exhibit: only the “historically significant” have been presented. Truly everyday objects will have been left out (by their very nature, anathema to preservation, longevity). And the tags that explain the place of these things in your life have no connection to how you think of them. Can the weight of habit be calculated in a few lines of type? You must imagine, too, people visiting this exhibit, looking closely before passing on to others, filling in their understanding of you as though you had been an empty vessel, a concept without any clear illustration; not a person at all. Are you there, at the center of the echoes of all those shuffling feet?

September 26th, 2011 / 12:51 pm

Sometimes People Put Writing on the Internet

I seem to remember there being a time when a whole bunch of writer types were really excited or really curious or really thinking deeply about using the internet to write stories, and because a page on the internet can be a place to place text and a place to place pictures and a place to embed music and a place to embed video and all that, it was going to be really exciting and revolutionary. And I seem to remember writer types in universities thinking maybe they had to jump on all this and think even more deeply about it and maybe thinking that they needed to start a whole side-discipline for hypertext.

I seem to remember all this, but it came and went so damn quickly, I can’t be 100% sure. And, frankly, I’m too tired to search it all out on the Internet Archive. Go for it, if you’re interested. If I made all of it up, give me hell in the comments section, maybe.

All that is just a prologue for two stories on the internet: OH NO EVERYTHING IS WET NOW, an ebook/web collage/thing/”pseudo small novella in verse” on our own Mike Young’s Magic Helicopter Press site, and “Neverland” by Gabriel Blackwell on the Uncanny Valley Press site. READ MORE >

July 7th, 2011 / 12:30 pm

Influences 2: Gabriel Blackwell

This is the second follow up to my “Let’s make a list,” art influences post. I asked Gabriel Blackwell to respond to these two prompts:

1) Pick one of the pieces you chose and describe the thing about it that seems particularly innovative about it.

2) Tell me what changed about your writing because of that innovation.

Here are his answers:

1) Roy Lichtenstein’s appropriation of Jack Kirby and Kirby-esque comic panels very nearly manages to carry us into the hip-hop age single-handedly. Yes, there are of course Duchamp, Warhol, and Lichtenstein’s other Pop Art contemporaries, but, for me at least, no one is quite so honest and unapologetic about the act of choice being the most important (so important that it can stand on its own) technique in the creation of art—and the subsequent ethic of recycling—as is Lichtenstein.

2) My mother and one of my older brothers are visual artists, and I was dragged—literally, by the arm—into a lot of museums and galleries as a kid. I probably hadn’t started writing yet, so I don’t think it would be fair to say that anything “changed” as a result. But I think that seeing Lichtenstein, in that context and at that age, permanently affected the way that I think of art—all art, including writing. The first story I can remember writing, when I was in 4th grade (so around the same time that my family and I went to MoMA and I first saw Lichtenstein’s appropriations), won first prize in my elementary school’s writing contest. A week later, the prize was stripped from me when it was discovered that I had lifted part of the premise of my story from Daniel Manus Pinkwater’s “Fat Men From Space.” I didn’t see anything wrong with it then, and I still don’t now.

ALSO:

Follow this link to Gabe’s blog and you’ll find a bit from a Paris Review interview with William Burroughs on cut-ups.