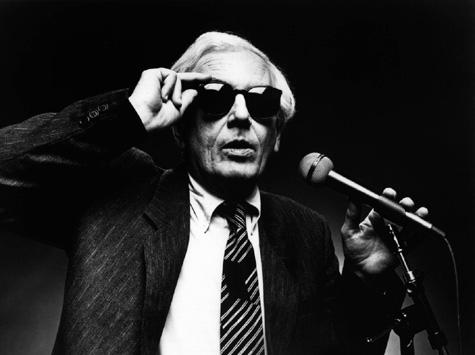

In memory of Robert Ashley, 1930–2014

I first learned about Robert Ashley through Peter Greenaway, thanks to his Four American Composers series. I rented all four videos because I was interested in John Cage and Philip Glass. I didn’t know who Meredith Monk was, or Robert Ashley.

As it turns out, the episode on Ashley interested me the most. I didn’t understand the opera being discussed, Perfect Lives, but I knew I had to hear and watch the whole thing. I took to the internet and discovered that I could order it directly from Lovely Music, on VHS. I did so. It cost me $100—but I had to hear it.

Few people I knew at the time had ever heard of Robert Ashley. When I moved to Illinois and met Mark Tardi and Jeremy M. Davies, we bonded in part over our shared love for Perfect Lives, “an opera for television” made in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It’s still not widely known. It’s still never been broadcast in its entirety in the US. But I’m not alone alone in regarding it one of the greatest operas and long poems in the English language. (John Cage wrote of it: “What about the Bible? And the Koran? It doesn’t matter. We have Perfect Lives.”)

Experimental fiction as genre and as principle

A few years ago at Big Other I wrote a post entitled “Experimental Art as Genre and as Principle.” That distinction has been on my mind as of late, so I thought I’d revisit the argument. My basic argument then and now was that I see two different ways in which experimental art is commonly defined.

By principle I mean that the artist is committed to making art that’s different from what other artists are making—so much so that others often don’t even believe that it is art. As contemporary examples I’m fond of citing Tao Lin and Kenneth Goldsmith because I still hear people complaining that those two men aren’t real artists—that they’re somehow pulling a fast one on all their fans. (Someday I’ll explore this idea. How exactly does one perform a con via art? Perhaps it really is possible. Until then, I’ll propose that one indication of experimental art is that others disregard it as a hoax.) Tao visited my school one month ago, and after his presentation some folks there expressed concern, their brows deeply furrowed, that he was a Legitimate Artist—so this does still happen. (For evidence of Goldsmith’s supposed fakery, keep reading.)

Eventually, I bet, the doubts regarding Lin and Goldsmith will fall by the wayside. Things change. And it’s precisely because things change that the principle of experimentation must keep moving. The avant-garde, if there is one, must stay avant.

That’s only one way of looking at it, however. Experimental art becomes genre when particular experimental techniques become canonical and widely disseminated and practiced. The experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, during the 1960s, affixed blades of grass and moth wings to film emulsion, and scratched the emulsion, and painted on it, then printed and projected the results. Here is one example and here is another example. And here is a third; his films are beautiful and I love them. (The image atop left hails from Mothlight.) Today, countless film students also love Brakhage’s work, and use the methods he popularized to make projects that they send off to experimental film festivals. (Or at least they did this during the 90s, when I attended such festivals; I may be out of touch.)

Those films, I’d argue, while potentially beautiful and interesting, are not necessarily experimental films. As far as the principle of experimentation goes, those students had might as well be imitating Hitchcock.

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 1: What is a concept?

Sol LeWitt: “Wall Drawing #1111: A Circle with Broken Bands of Color” (2003, detail). Photo by Jason Stec.

[Update: Part 2 is here.]

I wrote about this to some extent here, but I wanted to expound on the issue in what I hope is a more coherent form. Because I frequently see concepts confused with constraints, and the Oulipo lumped in with conceptual writing. For instance, this entry at Poets.org, “A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry,” states:

One direct predecessor of contemporary conceptual writing is Oulipo (l’Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a writers’ group interested in experimenting with different forms of literary constraint, represented by writers like Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, and Raymound Queneau. One example of an Oulipean constraint is the N + 7 procedure, in which each word in an original text is replaced with the word which appears seven entries below it in a dictionary. Other key influences cited include John Cage’s and Jackson Mac Low’s chance operations, as well as the Brazilian concrete poetry movement.

I would argue that the Oulipo, historically speaking, are not conceptual writers/artists—although it’s easy to see how that confusion has come about, because the Oulipians have proposed some conceptual techniques, such as N+7 (which I’d argue is not a constraint). (Also, it’s each noun that gets replaced, not each word.)

What, then, distinguishes concepts from constraints? And why does that distinction matter? In this series of posts, I’ll try answering those questions, starting with what we mean when we call art conceptual.

Another way to generate text #6: “word splitting”

“Split the stick and there is Jesus.” —John Cage

This is a simple technique and I will demonstrate it with this very sentence. First you take some language and split its words up. Then you write through it:

Th is i s a sim ple techn ique an d I w ill demon stra tei twi th thi s ver y sen tence

One of my favorite websites is OneLook, a dictionary search engine with wildcard functionality. Using it, I “completed” the split-up fragments:

100 things to do when you have the time

“There are people who say, ‘If music’s that easy to write, I could do it.’ Of course they could, but they don’t. I find [Morton] Feldman’s own statement more affirmative. We were driving back from some place in New England where a concert had been given. He is a large man and falls asleep easily. Out of a sound sleep, he awoke to say, ‘Now that things are so simple, there’s so much to do.’”

—John Cage, Indeterminacy

100 things to do when you have the time

- Doodle. Look for new styles, new approaches.

- Draw a picture of a friend. See how many different ways you can do it, such as how few lines you can use.

- Recite something you once memorized: a poem, a song, a story, a monologue.

- Memorize something new.

- Write a review of something you like.

- Go over the steps in a procedure or a process.

- Explain to a friend a thing you know, or think you know.

- Write a song, or cover a song.

- List the projects you’re working on, or want to work on. Set a deadline for completing one of them.

- Review every thing that you’ve done in the past week, the past month, the past year, the past five years, the past decade.

- Reread your diary or journal. If you don’t keep one, reread old sent emails.

- Describe something in as many words as possible, then as briefly as possible.

- Make up a riddle or joke.

- Make a puzzle for others to solve.

- Play a Dadaist/Surrealist/Oulipian writing game, such as automatic writing, the Exquisite Corpse, the Cut-Up Technique, homophonic translation, lipograms, …

- Write a story or poem entirely in your head.

- Observe whoever is around you. Note what they’re doing.

- Observe how the energy levels in a room change over time.

- Perform John Cage’s “silent piece” (4’33”). Pay attention to both the aural and the visual.

- Perform random FLUXUS pieces, then try inventing new ones.

- List all of your interests. Prioritize them.

- Compose a view.

- Explore a texture (a fabric, a liquid).

- Examine a nearby text. Why is it the way that it is?

- Explore a space: a room, a building, a street, a city.

Silence & Communication

A month or so ago, I was asked to write a response to the work of John Cage. And then, 21 other authors and I stood in a big circle around a crowd and read our responses. I thought I’d share mine with you.

3 OBSERVATIONS ON SILENCE (FEATURING HARPO MARX)

1

Imagine a long line of people, and a very important person—possibly with his wife, possibly with his security, possibly he is a she. The very important person is walking down the long line of people shaking hand after hand. Three quarters of the way down this line of people, the very important person comes upon a man in an overcoat and top hat. When the very important person sticks out his or her hand, the man in the overcoat and top hat does not in return stick out his own hand, but instead lifts his leg and deposits it in the hand of the very important person. READ MORE >

Seventy-one years ago today, John Cage debuted his prepared piano on stage at Seattle’s Repertory Playhouse. In honor, edit an old story of yours by adding a few new nouns.

“If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.” – John Cage

Thoughts about a Televised Performance of John Cage’s 4’33”

If I were a person who coughed at such a performance, or held a screaming baby, or whose cell phone rang, or who owned the corporation that operated the train which whistled as it went past the concert hall, I’d probably be embarrassed. I noticed that between the movements, people coughed more than the whole room of people had probably coughed in the entire day, probably because all of them had been so intent on holding their bodies still and holding their coughs during the movements. But the coughs they coughed between movements and the laughter they laughed after they coughed certainly represented the most enjoyable part of the performance, other than perhaps the conductor’s ad lib between movements, when he theatrically took a rag and wiped his forehead as though he had been working up a sweat with his conducting. (Maybe he had, but not because of exertion, but rather because of the tension that attaches to publicly not doing anything, and that was part of the gag, too, when he wiped his forehead with the rag.) READ MORE >