STARK WEEK EPISODE 1: “The redonkulous and the sublime” — An interview with Sampson Starkweather

WEEKS: A lot can kill you in a week. Even more can eat you at your weakness. A whole week of hair growth depends on, uh, genetics? Weeks contain a finite series of burritos and an infinite burrito of choices. Hoopla, regrets, collapses, dancing so hard you have to pour a cup of ice water on your dome, other times that feeling like you have to drag yourself so hard by your own collar your shirt might tear. Huge trucks at night carrying turned-off, unblinking versions of those normally blinking signs that say CONSTRUCTION AHEAD or SLOW LANE ENDS, except the signs are big so the trucks themselves say OVERSIZED LOAD and are blinking, themselves, even though their cargo’s dark. What I would like to do is nominate Sampson Starkweather to rewrite the entirety of America’s highway marginalia, to be the official roadside spokespoet for all of America’s restless feelings. I don’t have shit to do with those decisions, so what is happening instead is that this week will be Sampson Starkweather week here at HTMLGIANT, aka STARK WEEK.

WEEKS: A lot can kill you in a week. Even more can eat you at your weakness. A whole week of hair growth depends on, uh, genetics? Weeks contain a finite series of burritos and an infinite burrito of choices. Hoopla, regrets, collapses, dancing so hard you have to pour a cup of ice water on your dome, other times that feeling like you have to drag yourself so hard by your own collar your shirt might tear. Huge trucks at night carrying turned-off, unblinking versions of those normally blinking signs that say CONSTRUCTION AHEAD or SLOW LANE ENDS, except the signs are big so the trucks themselves say OVERSIZED LOAD and are blinking, themselves, even though their cargo’s dark. What I would like to do is nominate Sampson Starkweather to rewrite the entirety of America’s highway marginalia, to be the official roadside spokespoet for all of America’s restless feelings. I don’t have shit to do with those decisions, so what is happening instead is that this week will be Sampson Starkweather week here at HTMLGIANT, aka STARK WEEK.

THE BOOK: Sampson’s debut book of poems, The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather, is out now from Birds LLC. It’s really big. Like almost 400 pages. Who does that? It’s what it says it is. 4 books. All the feelings enacted in the opening paragraph happen inside of its four books, which are categorized as “poetry/life.” Sure, yes, yeah.

THE BOOK: Sampson’s debut book of poems, The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather, is out now from Birds LLC. It’s really big. Like almost 400 pages. Who does that? It’s what it says it is. 4 books. All the feelings enacted in the opening paragraph happen inside of its four books, which are categorized as “poetry/life.” Sure, yes, yeah.

WHAT’S IN IT: It’s a book I’d give to someone just coming to poetry and to someone who feels totally burnt out on poetry. Those are kind of the same readers, I think. That’s why the whole week. Starkweather’s poetry is the existence of a nonexistent photograph of Andre the Giant jumping off the top rope. In his introduction, Jared White mentions “bass-voiced sexy soul-singer slow jams” and “punch-drunk Harlequin-robocop masculinity.” The poems have angry leaked dreams and love before roads and a pistol-whipped desire and the world’s saddest TV and offensive hurricane names and corpses wrapped in huge tropical leaves on islands named after them and that’s just in the poems you can read on the excerpt page.

WTF IS GOING ON: Over the course of this week, we’re going to feature a series of guests talking about Sam’s work in each of the books within T4B—1) King of the Forest, 2) La La La, 3) The Waters, 4) Self Help Poems—and also we’re going to hear from the awesome artists who made the covers for each of these four books. There will be criticism, talk of process, grand sweeping theories, tiny insightful scalpels. You’ll get to read some of Sam’s poetry. There will be some talk of what goes into, in 2013, putting out a 400 page book of your poems that is actually 4 books. Maybe there will be some interaction, multimedia, surprise. Buy a copy of the book if you want to follow along closely. I promise it won’t feel like being stuck on a brokedown bus at a rest stop in Connecticut. There are poems that feel like that, but not in this book. Here’s a list of who’s coming at you: Matt Bollinger, Ed Park, Bianca Stone, John Cotter, Melissa Broder, Eric Amling, Elisa Gabbert, Jonathan Marshall, Amy Lawless, Sommer Browning, and Jared White.

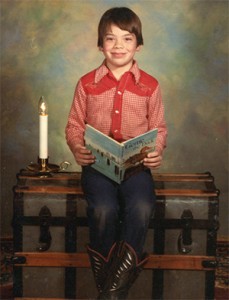

WHO IS SAMPSON STARKWEATHER ANYWAY, IS HE THAT GUY WHO DID THAT THING GUYS DO: The reason a lot of people want to share and talk about Sam’s huge ass tree-killer is because he and his work (which are impossible to unspoon from each other, which is how it should be) is like getting the best high five of your life from Teen Wolf. He is loved and easy to love and easy to mistake in rural supermarkets for Javier Bardem. He’s a longhaired poet surfer with a heart of messy pizza and manic kindness. Thank the exhausted fucking stars he is with us and with poetry. Enjoy STARK WEEK.

HOW DOES STARK WEEK BEGIN: To begin STARK WEEK, I talked to Starkweather:

1) Hi Sam. Welcome to Stark Week. This is how it starts, with an interview of you. Our interview starts with the “who is Sampson Starkweather and what’s going on, what is this stuff all over my arms, is this sap” portion of the interview. So let’s start at the start. Four books? Why? Why buck the prevailing model of slim little precious supermodel books? More importantly, why buck it in this beautifully thunking doorstop fashion?

Sorry about the sap “this forest / is unusually horny.”

In the end it came down to precisely the opposite of your question: “Why not?” Why not 4 books in 1? Why not a 328 page monster poetry collection that sounds like a seminal lifetime work by some famous, award-winning, about-to-die poet who now tends a garden, published by some big-ass conglomerate press like Penguin, but is actually by some dude with a ridiculous name that no one has heard of (and sounds like a character from Game of Thrones) and has yet to publish a full-length book, on a small indie poetry press that, oh yeah, he just happens to be a publisher/founding-editor of? It seemed ridiculous, audacious, absurd, unheard of, taboo, laughable—in other words, perfect.

In the end it came down to precisely the opposite of your question: “Why not?” Why not 4 books in 1? Why not a 328 page monster poetry collection that sounds like a seminal lifetime work by some famous, award-winning, about-to-die poet who now tends a garden, published by some big-ass conglomerate press like Penguin, but is actually by some dude with a ridiculous name that no one has heard of (and sounds like a character from Game of Thrones) and has yet to publish a full-length book, on a small indie poetry press that, oh yeah, he just happens to be a publisher/founding-editor of? It seemed ridiculous, audacious, absurd, unheard of, taboo, laughable—in other words, perfect.

July 15th, 2013 / 1:28 pm

Robinson Alone: An Interview with Kathleen Rooney

1. Excuse me for beginning with a rather longish question. Weldon Kees and Robinson are so durably linked, a bit inexplicably since Kees created a great deal of art, and “Robinson” appears in but four poems (to my knowledge). What is it about Robinson that emits such power? To borrow a term from Kees, what does it mean to be “Robinsonian?”

Actually, one of the things that makes those poems so compelling and unsatisfying is that there are four of them. If Kees had followed the rule of threes, then they’d probably be known as the Robinson Trilogy, and that would be that: done. But there’s something about there being four of them that calls for addition. Four is a bad luck number in Japan associated with death. I think that I—and other people who’ve done individual Robinson poems over the years since Kees vanished—read the fact that there are four of them as a kind of permission or even an invitation to take over. Like he’s saying “Obviously, guys, I wasn’t finished.”

As to what it means to be Robinsonian, not to be glib, but the poems in Robinson Alone are kind of an attempt to figure that out. Kees’ Robinson is stylish, worldly, and extremely anxious, but these are four very mysterious poems that present themselves as mysteries that open up onto other mysteries.

2. What is your opinion on fame in a writer’s life? Follow up: would you like to be famous?

Wait—you mean I’m not famous?

J/k! Fame in a writer’s life and fame in general is fascinating, but as an ontological state that a person has to inhabit, it seems dangerous—a trap. Last Fall, I read Eileen Simpson’s excellent memoir Poets in Their Youth which is about her marriage to John Berryman, but it’s also about how so many of those mid-century poets who were Kees’ contemporaries—Berryman, Randall Jarrell, Robert Lowell, and Delmore Schwartz—wanted to be, and sometimes were, famous. Simpson makes it sound as though any position along the fame spectrum—wanting it, thinking you deserve it, pursuing it, getting it, losing it—made them fairly miserable, although, of course, they thought fame would make them happy. I want my books to be read and I want people to have heard of me, but fame as such is not a thing I “want.”

3. I sometimes think contemporary poets have little understanding of prosody, classical forms, the structural history of poetry. You (as did Kees, of course) seem to have a very strong understanding of these techniques. Why is this important to your poetry?

Vanity Fair or Unfair?

At The Rumpus, Vanessa Garcia reviewed Kathleen Rooney’s new essay collection, For You, For You I am Trilling These Songs. Garcia’s consideration was highly ambivalent, and she ultimately rendered a verdict against. Then all hell broke loose in the comments section. Daniel Nester, Kyle Minor, Elisa Gabbert, and Tim Jones-Yelvington are just some of the local (to us here) luminaries who weighed in with complaints against the review. Rumpus Books editor Andrew Altschul has responded several times; he and Nester are particularly aggressive with each other. What makes this more interesting than a flame war is that the vitriol seems not excessive, but central and perhaps necessary, to an earnest conversation about how nonfiction–memoirs in particular–ought to be read and discussed. My one critique of said discussion is that there seems to be an undercurrent of umbrage–palpable but pointedly not articulated–at the fact of a negative review having been written at all. Critics who pan things should expect to have their prerogative cross-examined, their biases speculated upon, their motives questioned, etc.–which is not to say that Garcia’s critics are wrong, only to point out that a positive review is never reprimanded for its angle, however wrong-headed or idiotic that angle might be. If we are willing to court and accept facile praise, do we have the right to demand anything better from our detractors? (Again: not to suggest Garcia’s piece is facile, or “wrong”; having not read Rooney’s book I withhold judgment on both it and the crit of it.) Anyway, the comment-thread is still active as of this morning, and the whole thing is worth giving a look to.

At The Rumpus, Vanessa Garcia reviewed Kathleen Rooney’s new essay collection, For You, For You I am Trilling These Songs. Garcia’s consideration was highly ambivalent, and she ultimately rendered a verdict against. Then all hell broke loose in the comments section. Daniel Nester, Kyle Minor, Elisa Gabbert, and Tim Jones-Yelvington are just some of the local (to us here) luminaries who weighed in with complaints against the review. Rumpus Books editor Andrew Altschul has responded several times; he and Nester are particularly aggressive with each other. What makes this more interesting than a flame war is that the vitriol seems not excessive, but central and perhaps necessary, to an earnest conversation about how nonfiction–memoirs in particular–ought to be read and discussed. My one critique of said discussion is that there seems to be an undercurrent of umbrage–palpable but pointedly not articulated–at the fact of a negative review having been written at all. Critics who pan things should expect to have their prerogative cross-examined, their biases speculated upon, their motives questioned, etc.–which is not to say that Garcia’s critics are wrong, only to point out that a positive review is never reprimanded for its angle, however wrong-headed or idiotic that angle might be. If we are willing to court and accept facile praise, do we have the right to demand anything better from our detractors? (Again: not to suggest Garcia’s piece is facile, or “wrong”; having not read Rooney’s book I withhold judgment on both it and the crit of it.) Anyway, the comment-thread is still active as of this morning, and the whole thing is worth giving a look to.