Selection from Q.E.D. – Part 1, “Things Unsaid”

The MAK Center Schindler House, Los Angeles

11 April 2012

Compiled by Chris Hershey-Van Horn

Context Note: In April, May, and June of this year, Les Figues Press hosted a short series of long conversations on queer art and literature. Titled Q.E.D., in honor of Gertrude Stein’s novel by the same name (and one of the earliest coming-out stories), each Q.E.D. event explored the constructions of speech, art, literature, materiality, and sex. The conversations were moderated by Vanessa Place at the historic MAK-Schindler House, L.A.’s original nod to green architecture.

Q.E.D. Part One featured Melissa Buzzeo, Patrick Greaney, and Simon Leung.

***

“What happens in a work of art when it seems like the artist does nothing?”—(Patrick)

July 2nd, 2012 / 12:00 pm

I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 5 (Talking With the Eds.)

While working on my initial review of I’ll Drown My Book last spring (2011), I posed a few questions to the editors. Here are some of their responses…

***

To Laynie Browne:

Many of the characteristics you give for Conceptual Writing, seem to me, be able to also describe what “good experimental writing” ought to be, in some ways. Though I’m sure we would agree on the problematics of the term “experimental,” and maybe more so with “good” and “experimental” juxtaposed, I’m thinking about some of the features you mention: “a recasting of the familiar and the found,” as defined by “thinkership,” often filled with “an assemblage of voices,” “process is often primary and integrative,” “the unknown and investigative are common impulses,” “the desire to reveal something previously obscured,” etc. It seems to me many experimental writing projects would share these characteristics. Might you agree? What makes Conceptual Writing stand out from other experimental writing projects? READ MORE >

June 8th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 4: Why Nobody’s Going to Read This Review, or That Book—The Fate of Conceptual Writing by Women in an Age of Corporate Blood Lust, State Mayhem, Social Retardation, and Personal Horror

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

Edited by Caroline Bergvall, Laynie Browne, Teresa Carmody, & Vanessa Place

Les Figues Press, 2012

455 pages / $40 Buy from Les Figues Press

An anthology is a gathering of flowers. Flowers want to live hidden lives. They desire not the sun, which is ugly to them, but to be unknown. Name a flower, ruin its simplicity. I write this with all the sincerity of a saint, that is, a criminal: flowers abhor pretense—the sincerest of affectations. They are far from being nature’s perfect little girls.

When I say: flower—outside the oblivion to which writing, all writing, relegates any shape, there arises musically, as the very idea, and delicately, the one absent from every bouquet. I’ll Drown My Book is the absent flower from the bouquet of today’s writing. It marks writing’s impossible edge with a billion dots we will never see but that somehow fuck with us—it traces writing’s secret punctum that we stupidly confuse for stars.

June 7th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 3

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

Edited by Caroline Bergvall, Laynie Browne, Teresa Carmody, & Vanessa Place

Les Figues Press, 2012

455 pages / $40 Buy from Les Figues Press

(Disclosure: I honestly had no idea when I requested the book but note that it contains the work of some of my friends, acquaintances, teachers, mentors, and personal heroes, though the widescreen approach in curating the book’s 64 writers works against me simply cheering on a select group or writer to whom I’m personally attached.)

Prior to reading I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women, my general, sloppy idea about conceptual writing was that it was only the kind of writing where the experience of appropriated text as object/concept was more important than the experience of reading what’s been sculpted into book form for “literary” value. Instead, I’ll Drown My Book offers approaches to encountering and writing text as various as the writers included and as familiar as “appropriation,” “intertextuality,” “hybrid” and “constraint,” named in the book alongside “dissensual,” “baroque,” and thirteen other broad categories as forms conceptual writing might take.

What’s important and unique about the writing in I’ll Drown My Book isn’t what strategy is being employed but the fact that there is a strategy, and often a structure. (The two being different in that strategy involves an approach guided by a given or created set of rules while structure involves use of a given or created form other than a continuous or broken line.) You could claim that all writing is strategic in some way with respect to what decisions you make when you set out to write anything but the writing in the anthology is strategic specifically because the strategies are local, formal, and often overt vs. obscured from the reader. Conceptual writing, here, is not a movement but a methodology, a way of viewing writing as always following and rewriting a myriad of different kinds of other texts, or by replacing “writer” with text. Just for the sake of contrast I’m claiming the nominal state of what let’s call “normative” writing is that you can and do claim sole authorship,over additive and usually linear text, starting off in your headspace with an idea or image or voice that seems worth pursuing and building on it alone, meaning, in the words of Frank O’Hara, you just go on your nerve.

June 6th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 2

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

Edited by Caroline Bergvall, Laynie Browne, Teresa Carmody, & Vanessa Place

Les Figues Press, 2012

455 pages / $40 Buy from Les Figues Press

One half of a knucklebone or other object was a common object to carry in ancient Greece as an identifier to whoever carried the other half: a symbolon, the root of the word symbol. A symbol is a half-thing but of course most things are half-things; otherwise, what is language for? It fossilizes the potential of objects into meaning. Art has that to deal with. Language that knows it is art, on the other hand, seems to seek objecthood.

A walk through a regular art museum might have you thinking art is paintings. A distant second to that is sculpture, then drawings and prints, etc., and the farther the object deviates from these materials (or if the object was made for any other purpose than aesthetic contemplation, say, a quilt), not only is it less likely the object will be canonized (without any modifying category) as art, but the more the object will require mediation, textual padding between audience and object.

Perhaps what makes a work Conceptual, then, in visual art and in writing, is that as an object it attends to its physical deviation from canonical works but also shifts its weight to its context rather than its object. “A construction [is] a beginning of a thing,” wrote Yoko Ono in her Conceptual art book Grapefruit, and in this view, an object or a text is an idea’s anchor that begins, rather than completes, the idea.

The writings in I’ll Drown My Book are surrounded by frames: two introductions and one afterword by the editors. Each selection is then also followed by a writer’s statement, often a description of the work’s procedure or a response to the term Conceptual as it applies to her work. This textual-framing reminds me very much of how the visual arts are presented, propped by text panels in galleries and museums, battened by artist’s statements in magazines and catalogs. And ultimately, Conceptual writing itself is consciously framed by the Conceptual art movement of the 60s and its earlier predecessors in Dada and related movements; solidified by Duchamp in 1917 in his defense of his readymades which refused to supplement art objects with context but instead supplanted them with context. But Conceptual art, just as it is in writing now, never came to define a precise artistic practice, and because of this it became a convenient bag to throw anything that didn’t seem like art. In other words, art that was hard to sell: performances, happenings, instructions, installations, ephemera, sounds, silence. In dematerializing of the art object, artists were certainly responding to the hyper-commodification of contemporary art and its increasingly opaque economics.

June 5th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 1 (The Ghosts of I’ll Drown My Book)

This is Part 1 of a week long feature on I’ll Drown My Book, the new anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press.

Stay tuned all week for more…

6/4 Monday – Part 1: Review by Janice Lee

6/5 Tuesday – Part 2: Review by Molly Brodak

6/6 Wednesday – Part 3: Review by Nicholas Grider

6/7 Thursday – Part 4: Review by Janey Smith

6/8 Friday – Part 5: Brief interview questions with the anthology’s editors

*** READ MORE >

June 4th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Contesting Contests: A Conversation

A while back, I posted a link to Les Figues Press’s very first book contest. Whereas all I did was post the submission information, many commenters responded, asking questions and giving opinions about contests in general. To clear up any questions about motivation, profit margins, etc, I have assembled four small presses – Les Figues Press, Starcherone Books, Noemi Press, and Fiction Collective 2 – to discuss their contests. I hope you find this conversation as illuminating as I do.

Bios for the presses can be found after the conversation. The publishers representing the presses are as follows:

Les Figues Press (LFP) – Teresa Carmody

Starcherone Books – Ted Pelton

Noemi Press – Carmen Gimenez Smith

Fiction Collective 2 (FC2) – Lance Olsen

Note: You may notice an exclusion in the conversation here, that is, I didn’t ask anyone to represent a press who doesn’t have a contest. I had considered asking a few people, but ultimately, I wanted to focus on why presses have chosen to run a contest. Expect a post within the next few weeks with presses who have chosen not to run a contest, for whatever reason. Hey publishers: if you have a press that doesn’t run a contest and want to participate in a conversation like this one, email me: Lily [dot] Hoang [dot] 326 [at] gmail [dot] com.

LH: How long has your press run a contest, and what was your rationale in starting it? Do you require a submission fee? With the submission fee, does the applicant get any other goodies?

AT LAST, SEXUAL SATISFACTION FOR CINDY SHERMAN WITH YOUR BIGGER AND NEWEST ATEMPORAL NETWORK CULTURE!

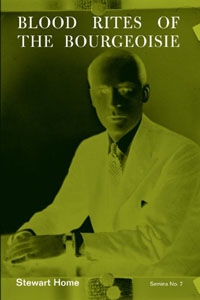

Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie

Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie

by Stewart Home

Book Works, 2010

120 pages / $19.99 Buy from Amazon

&

The New Poetics

by Mathew Timmons

Les Figues Press 2010

112 pages / $15.00 Buy from Les Figues

If you’re anything like me, you’re probably keen on the emergent discourse surrounding our current atemporal, altermodern new media status. Facebook, Flickr, Google, iPad, iPod, Myspace, Youtube, etc, etc: its all grist for contemporary philosophers, and writers too have attempted to capitalize on the ubiquity of Twitter feeds and Facebook updates – with mixed results. Zen literary terrorist Stewart Home and Los Angeles-based poet Mathew Timmons are both authors of recent books that are candidates for an emergent atemporal literature (for lack of a better term); what Home and Timmons have managed to do is to avoid the trap of the ever-expanding rotting mounds and heaps of aspiring internet-based fiction, and needless to say – that trap is the perennial lure of narrative storytelling.

August 1st, 2011 / 12:00 pm

Got a manuscript? Enter a contest.

Les Figues Press is having a contest. Find out more about here. 1k + publication. All entrants get a free TrenchArt book of their choice. And there are many good choices.

Les Figues Press is having a contest. Find out more about here. 1k + publication. All entrants get a free TrenchArt book of their choice. And there are many good choices.