25 Points: The Tunnel

The Tunnel

The Tunnel

by William Gass

Dalkey Archive Press, 2007

652 pages / $15.95 buy from Dalkey Archive Press or Amazon

1. It took the man 26 years to write this thing. Let’s just get that out of the way now.

2. Semi-autobiographical, with an ornate use of language, penis obsessed, full of stupid limericks about horny nuns. It’s in the vein of Joyce and Pynchon but maybe not as annoying, not as smug–though maybe I’m wrong about that.

3. I did find the book unusually satisfying. Just sitting down and reading Gass’s prose out loud is really enjoyable: rhyming and alliteration are present at all points but Gass weaves the sounds into the thought and plot without being gratuitous. He does it joyously, gallopingly. He moves things along at a decent pace and lets you feel every increment.

4. The narrator William Kohler is a terrible person who you learn to love. He’s a fascist, misogynist, grumpy fat old fuck and you get to see inside his head and understand why he is all of these things. If you are the sort of person whose life can be changed by books this may change you so you can appreciate the shittiest people on this planet.

5. Plot is minimal. If anything “happens” it is the digging of the eponymous tunnel though that whole part is really pretty minor anyways. The majority of the book follows Kohler examining his childhood, his education, his marriage, family, coworkers and anger. Always the anger, the disappointment.

6. Kohler has two kids. Throughout the book he can only remember one of their names. Genius.

7. The descriptions are, without a doubt, beautiful. Candy, flowers, interiors, and people especially. Gass builds the characters up from thousands of scraps, always describing over and over, adding and sticking on and plugging holes. The characters come off as straddling an incredibly thin line between being fully developed and total caricatures. It works because we are inside Kohler’s head the whole time, and don’t you always caricature those you are forced to be around?

8. Degenerative sickness strikes a number of those around Kohler. Those he loves and hates. These depictions are gut wrenching and we get to see the characters before and during, before and during, before and during their declines. Seeing Kohler’s brilliant mentor go through sickness then back to health is particularly rough for we know that soon enough he will be back on the sick bed twitching and jerking. It’s like Gass gives them a reprieve just so he can suck them back through their crumbling one more time.

9. There is this depiction of academic life toward the beginning of the book which (though never having lived it myself) seems entirely appropriate: “Life in a Chair.” Kohler looks back and realizes he’s spent his entire life just sitting, reading, sometimes looking out a window. He never succumbs to sadness or regret, just puts it out as a solid fact and meditates on it to great length. This section should be read by anyone who wants to go into academia I think.

10. There are few people in Kohler’s life who are not totally insane. READ MORE >

May 28th, 2013 / 5:01 pm

The Doorknob Passage – A Conversation with Bennett Sims

I’ve never read a zombie novel, and after reading A Questionable Shape, the debut novel from Bennett Sims, which has been described as a zombie novel, I still haven’t. We see glimpses of rabid zombies on grainy mall security cameras, ghost-like versions in a field, and zombies crowding a police car, but the book is more about retracing our memories, how to deal with loss, and ultimately, how to live in a world falling apart around us. It’s a philosophical mind-fuck of a novel filled with illuminating sentences and dark footnotes.

Bennett and I traded emails to discuss his time as a student of David Foster Wallace, paranoia, insecurities, influences, and push-ups.

Shane: So, how are you feeling?

Bennett: It’s the end of the semester, so I’m feeling somewhat hollowed out. This year I was teaching an undergrad fiction workshop here at the University of Iowa, and I wrapped up all my grading yesterday. Nabokov has that line about finishing a work, how he feels like ‘a house just emptied of its grand piano.’ It’s a little like that—except that instead of producing beautiful music, the part of me that’s missing is used to shooting off workshop letters and miscellaneous correspondence. So I guess I’m feeling like a house just emptied of its fax machine, which is a different kind of quietness. How are you feeling?

Shane: I’m depressed because I’ve been doing nothing but eating cookies and drinking coffee and now I’m crashing from it. I’ve never heard of that Nabokov line before but I like it. Pale Fire is a beast and my favorite of his. Did Nabokov influence A Questionable Shape? I see some of his wordplay and magic in your sentences.

Bennett: Sorry to hear about the cookie-and-coffee comedown. I usually have to take a nap when that happens.

Thanks for the kind words about the book. I’m flattered by the Nabokov comparison. He’s definitely a background influence—one of the stylists I’ve admired longest, whose sense of wordplay and whose sheer felicity of description I’ve tried to absorb. But I was not thinking about any particular work of his when drafting A Questionable Shape. The footnotes, for instance, were self-consciously modeled on Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, rather than Pale Fire.

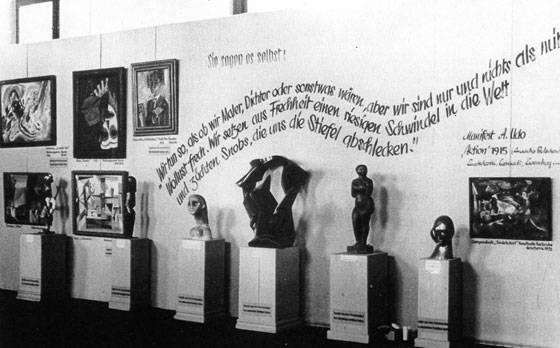

EMBRACING POWERLESSNESS IN DEFINING ART : THE LEGACY OF ENTARTETE KUNST (1937)

The Stayin Alive of the Gallery Show-An IRL Victory

The insightful and highly regarded art-critic Jerry Saltz recently wrote an ambiguously polemical essay in which he crywolfed the death of gallery shows1. The primary theme of his argument is linked to the Internet’s takeover of the sales departments and the URL-manner in which the contemporary art world functions now, eliminating the necessity for the IRL-dimensions of the process.

Discussions that pertain to the broader implications of the Internet in an industry rarely reach an objective conclusion. The art industry undoubtedly constructs a particularly challenging case due to its multilayered and convoluted business model. The argumentation may be shifted in any direction to build a persuasive case for any involved party. Artists gain significantly by creating a powerful web presence: they increase their chances of being discovered and attaining the attention of individuals who may shape their future. Additionally, a much larger audience has accessibility to viewing and becoming familiarized to the work of countless artists through a net simulacrum. Whether they simultaneously “lose” by offering their presence is ultimately subject to their ideology.

In a brusque manner, Saltz asserts that the only criterion in evaluating gallery shows are the sales they garner, or fail to garner. The critic briefly articulates–but neglects to delve into the magnitude of–how this shift relates to his identity as a critic. It would be naive to ignore how the “democratization of the critic2” affects him personally: his role becomes less important offline, as the presence of less people at galleries has an impact on the pragmatic utilization of his hard-earned credentials and expertise.

When accounting for this detail, an evident controversy in Saltz’s essay arises: initially he brings attention to the lack of a meaningful dialectic occurring in physical gallery space, while he later hesitantly adheres to the democratization of criticism by adding that “art is not inherently democratic.” What critic wants to experience others’ seeking of his expertise and input decrease? Saltz does a better job at identifying “the problem” by stating that the “the art world has become more of a virtual reality than an actual one.” Whether it ever was an actual one, or if it solely seemed so to the critic remains debatable.

“The Death of the Gallery Show” introduces a compelling argument. It is interesting to place it in the framework Thomas Frank recently utilized to investigate the authenticity of political statements of David Leonhardt on the topic of economic austerity. Frank’s methodology falls in line with the familiar traditional debate approach: “The point wasn’tfor an individual debater to believe any particular argument and win the room over with the radiance of his faith; it was for him to be able to argue anything.3”

While Saltz argues the end is near, I am not convinced he deems it possible. In a fascinating way, his performativity of argumentation is representative of the very reason galleries constitute alienating spaces for most people: much of the art presented today cannot be a catalyst for discourse. The curatorial content is no longer created for the audience, but is expected to be created by it. Certainly, this has been argued before, but the status quo of modern art has never before been as deeply interconnected with the mass entertainment industry.

The difference between Jeff Koons’ notorious sculpture of Michael Jackson with his beloved pet Bubbles and Tilda Swinton’s celebrated naps at the MoMA is a drastic paradigm of the shift that occurred within this time in the collective consciousness of reality4. Even if we are so alone in our virtual worlds that we need to be made aware of it via art, this never becomes sufficiently clear in such grotesquely self-aggrandizing projects. This intentionality in mirroring whatever the audience wants to see can be powerful, but it cannot escape being contrived. Ultimately, it appears as if the art world viewed drawing more elements from the entertainment industry as a means to attract more people and yield better sales. The performed bravado and intentional ambiguity of such contemporary art projects make people show up in gallery spaces less frequently. Why turn to culture when the culture is the entertainment?

25 Points: The Stud Book

The Stud Book

The Stud Book

by Monica Drake

Hogarth, 2013

336 pages / $25.00 buy from Amazon

1. Monica Drake has written a compelling novel of manners.

2. The Stud Book follows a group of adult friends in Portland, Oregon (aka everyone living in America today) as they reconcile expectations with reality.

3. There is a zookeeper, a mortgage underwriter, a photographer, a yogi, and a computer repairman. Unsurprisingly, hilarity ensues.

4. Drake diffuses the novel’s many anticlimaxes (mishaps, muddled careers, domestic failings, generally unrealized ambitions) with a singular sense of humor.

5. The Stud Book is a book about motherhood. And the baby jokes crackle. A woman mistakenly licks a bit of dirty diaper from her shirt (not mustard!); another knocks an Oxycodone into an infant’s mouth. Drake exploits babies like the vulnerable little props they are.

6. Drug humor abounds as the friends imbibe in the manner of well-established stoner citizens. Justifying a “Volcano” vaporizer at a high school assembly one says, “I’ve got a chronic pain problem. This is totally legal.” Another drives high, she “ignoring the dosing instructions… nibbled pills all day long.” “She’d started to see the benefit: a military dose of Klonopin with red wine, dished out like a free lunch, would end the troubles in the Gaza Strip.” “Her car was speckled with pink, pale yellow, and white pill crumbs, Klonopin, diazepam, Vicodin.”

7. But beyond bad behavior, Drake finds a gentle humor in frailty.

8. On justifying the purchase of a derelict storefront, “Crack addicts curled in the recessed doorway and cans of OE8 littered the curb, but there was a Starbucks practically next door. Starbucks with their market research was an indicator the neighborhood was poised for an upswing.”

9. On Mrs. Cherryholmes, the beautiful but villainous school principal, “Her lipstick was frosted, too, in a sheen of confidence. That was probably the actual lipstick color: Administrative Confidence.”

10. One particularly funny and gruesome scene of self-love is a shoo-in for the annual bad sex in writing award, “He spit on his hand, cupped it and rubbed his damp palm over the head of the cock.” READ MORE >

May 14th, 2013 / 5:35 pm

Soderbergh on Cinema is Soderbergh on Publishing

Film director Steven Soderbergh recently spoke at the 56th annual San Francisco International Film Festival. Before the speech Soderbergh said he would “drop some grenades.” Rarely does that happen. But what Soderbergh did was special – he pierced holes into an industry that is corporatizing and mainstreaming a once beautiful and individualistic art form.

I’m not a student of film nor would I consider myself knowledgeable on the industry. So after I read the full transcript of Soderbergh’s speech I wondered why I was so captivated. The answer was simple: I was reading a speech about the state of film, but as a writer, I was reading a speech about the state of publishing.

Soderbergh’s main sticking points: a bigger film budget yields bigger results, those in charge at the studios don’t watch cinema, artists need to be supported financially long term, ambiguity is toxic to a mainstream audience, and too much emphasis is placed on testing and pre-sales numbers, may sound like sour grapes to some, but I believe he’s accurate. I believe what he says about the state of cinema is in direct correlation to how I, and many, feel about the state of publishing.

Soderbergh loves strangeness and ambiguity in film. The ambiguity in my second novel, published by Penguin, was questioned by my editor. The push to extend the “reality storyline” in the book became a main focus during revisions. There had to be more of a love story. Things had to make sense. Sentences deemed strange and vague were questioned with “I really like this, but what does it mean?” The push for things to “make sense” has resulted in boring movies and boring books. READ MORE >

25 Points: what purpose did i serve in your life

what purpose did i serve in your life

what purpose did i serve in your life

by Marie Calloway

Tyrant Books, 2013

200 pages / $19.00 buy from Amazon or SPD

1. The film The Hurt Locker opens with the quote “The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug.”

2. Marie Calloway’s novel what purpose did i serve in your life opens with the quote “We teach children not to go into stranger’s houses, so why do it as an adult?”

3. The film The Hurt Locker is divided into a number of distinct scenes showcasing Sergeant First Class William James’ deactivating various bombs in intense, maverick ways. The viewer is left with the post-suspense of the diffusal, the slowing of blood-pressure lets one reflect on war as the hazmat is removed.

4. Marie Calloway’s what purpose did i serve in your life is divided into a number of distinct reflections each culminating in some kind of sex which she somehow coordinates in an often intense, maverick-y way. When being degraded, she posits that she deserves it. She states she feels relief and confusion in making herself an object.

5. The movie The Hurt Locker portrays James’ fearlessness in the face of danger and ends with his inability to escape the very thing that is destroying him.

6. Marie Calloway’s novel portrays a young woman moving through life after vaguely mentioned past traumas. She is a rape victim and this shapes her sexual actions and reactions. Though often being grossed-out or averse to a range of sexual suggestions (from being eaten-out to force-fed her own vomit) Calloway’s actions are that of a compliant, non-confrontational lover.

7. In 2011, Gawker called Marie ‘just a girl, with a Tumblr’.

8. In the Jeremy Lin chapter of the book, Lin points out:

“If someone says your writing has flaws or is good, that implies they know a concrete goal that your writing has, which can be measured in numbers, and that the number would be higher or lower if you changed your writing in a certain way, I feel, by that seems incredibly hard to measure, even if two different people had agreed upon a purpose for your writing that could be measured, like ‘increases heart rate in reader’ or something. But it can be depressing to never think in terms of ‘good’/’bad’ without defining contexts/goals in each instance.”

9. A staff member of the Paris Review once told William S. Burroughs that sex seems frequently equated with death in his writing. Burroughs responded:

“That is an extension of the idea of sex as a biologic weapon. I feel that sex, like practically every other human manifestation, has been degraded for control purposes, or really for antihuman purposes. This whole Puritanism. How are we ever going to find out anything about sex scientifically, when a priori the subject cannot even be investigated? It can’t even be thought about or written about. That was one of the interesting things about Reich. He was one of the few people who ever tried to investigate sex—sexual phenomena, from a scientific point of view. There’s this prurience and this fear of sex. We know nothing about sex. What is it? Why is it pleasurable? What is pleasure? Relief from tension? Well, possibly.”

10 a. “If you like me, you have to like shyness.”

b. “I’m smart at some things but not with people or at growing up.” READ MORE >

May 9th, 2013 / 12:26 pm

25 Points: Solip

Solip

Solip

by Ken Baumann

Tyrant Books, 2013

200 pages / $14.95 buy from Amazon or SPD

1. Solip isn’t a novel.

2. If you’re looking for plot, look elsewhere.

3. This might be the single most difficult book to write jacket copy for.

4. This isn’t experimental literature for the sake of experimenting.

5. The book is physically tiny and the front cover is minimalist.

6. There is nothing on the back cover. A wall of black staring at you. No pull quotes or blurbs, and by the second page you realize why: because the book speaks for itself.

7. I read this tiny book in one sitting in a coffee shop amazed by its power and had to go indoors to drown out the outside world to reread it and devour it properly.

8. Baumann’s writing demands your attention. It’s as if he’s bottled up the intensity present in much of online fiction and spread it out over a longer narrative, not losing a beat in the process.

9. The sentences are divine. The language will cast shadows. They will hum to you. Listen closely.

10. The book has a pulse to it, a pulse that beats louder and more pervasively as the text unfolds. READ MORE >

May 7th, 2013 / 3:01 pm

25 Points: Light and Heavy Things

Light and Heavy Things

Light and Heavy Things

by Zeeshan Sahil

BOA Editions, 2013

56 pages / $16.00 buy from BOA Editions

1. this is such a nice song oh my god http://www.youtube.com/

2. Zeeshan Sahil was born in Hyderabad, Sindh in the ‘60s. He wrote within a fairly small and well known circle of Pakistani poets who to my mind are the Urdu answer to Bolano’s Infrarealismo movement. -A lot of prose poetry going on, a lot of experimenting with if not ignoring meter and rhyme entirely. A lot of art.

3. He published eight collections of poetry in Urdu (mostly free verse though) and also wrote for broadcast radio which is no small thing for someone in Pakistan in the time period.

4. Experimental poets writing for radio in a war torn area, kinda a thing.

5. This book is 56 pages and it took a team of three translators to bring it into English.

6. Sometimes he writes from the perspective of a woman, I think.

7. I sometimes wear lipstick to make a point.

8. He makes his point in such a quiet way, in such a vulnerable, elegant, this thin glass lightbulb could shatter in your hands at any minute way, that it’s disarming, astounding. Like eerily demure. Entirely manipulative and totally works for him.

9. “I’m not saying, I’m just saying” all over these pages. All day long with the vulnerability in his manipulativeness.

10. We forgive him. READ MORE >

May 2nd, 2013 / 12:05 pm

25 Points: American Psycho

American Psycho

American Psycho

by Bret Easton Ellis

Vintage Books, 1991

416 pages / $15.95 Buy from Powell’s or Amazon

1. A few weeks ago, I took a break from holing up inside my apartment and writing my thesis to walk to Powell’s Books here in Chicago. I mostly just wanted to get outside for a minute, but I ended up walking around the bookstore for an hour. I first grabbed Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho and a John Cheever story collection, then decided I didn’t want the Cheever but accidentally put the Ellis back instead. In retrospect, this seems like an unheeded signal from the Book Gods of the universe not to read American Psycho.

2. Bret Easton Ellis has been on my mind twice recently: (1) his Twitter rant about David Foster Wallace where he called the writer “the most tedious, overrated, tortured, pretentious writer of my generation” and “a fraud” (2) his tweet about Tao Lin’s upcoming novel Taipei: “With ‘Taipei’ Tao Lin becomes the most interesting prose stylist of his generation, which doesn’t mean that ‘Taipei’ isn’t a boring novel…”

(I guess what I really had on my mind, then, was Bret Easton Ellis’s Twitter account). So I connected “master prose stylist” and Bret Easton Ellis in my head. After reading the book, I stand by that statement.

3. The place where I felt creepiest while reading American Psycho was eating alone at a diner. It had eerie resonances with the scene in Sandman: Preludes and Nocturnes where John Dee enters a diner and whips all the customers into a crazed frenzy, causing them all to kill one another within 24 hours. Like American Psycho, there’s flesh mutilation and cannibalism in this Sandman scene. Luckily, the worst damage to me that night was my friend blowing me off (hence, the eating alone).

4. My cover has these almost delicate ribbons of what is presumably blood, but it’s light red, shading off into pink at parts, and doesn’t blood darken when it dries? It could just as well be wisps of smoke…red smoke…and this could just as well be a novel about drugs, which play no small part in the book.

5. A Time Out blurb on the back proclaims that American Psycho “examines the mindless preoccupations of the nineties preppy generation.” It was first published in 1991, though, so I guess that makes the book a harbinger of the decade that was to follow. Another blurb calls American Psycho a “satire in which the hedonistic, coke-fueled consumerism of the Eighties was taken to its brutal conclusion.” Q: is this a novel of its time, tied closely to the period in which it was written and set? Will we be reading American Psycho differently, or at all, in 50 years?

6. There’s plenty here to date the story, mostly technology-wise—videotapes, compact disc players, no cell phones—but what keeps signifying “90s” to me is the pervasiveness of cocaine. There’s a lot of coke here, people using it, people trying to get it. At one point, main character Patrick Bateman’s credit card snaps in half from being constantly used to do the drug.

7. Basic plot: American Psycho is about a closet psychopath, the moneyed Wall Street banker Patrick Bateman, following him around Manhattan as he violently tortures and murders various individuals. Many of his victims are women, some men; lots are existing acquaintances of his, some are unknown parties—homeless people, delivery boys, and prostitutes—and some are animals. Bateman displays a particular (and racialized) cruelty towards beggars, hitting them with the familiar “get a job” lines and dangling dollar bills in their grasp then snatching them away. For Chrissakes, one of his victims is a 5-year old child at the zoo.

8. American Psycho was turned into a movie in 2000, directed by Mary Harron and starring Christian Bale, Chloe Sevigny, Reese Witherspoon, Jared Leto, and Willem Defoe. I have not seen the movie. Of the friends I’ve told that I’m reading this book, most have seen the movie and about half have read the book. I keep getting it confused in my head with the movie American Beauty (1999), which also portrays murder, but only a single one.

9. I think I’ve twice had to tell people that this is my first Bret Easton Ellis book, which makes me feel like a poorly-read cretin.

10. Bateman meticulously reports on the dress of most every male and female character and stranger he encounters, along with his own attire at every turn. Like, there are just a lot of brand names, proper nouns, in this book. Sample line: “Price is wearing a six-button wool and silk suit by Ermenegildo Zegna, a cotton shirt with French cuffs by Ike Behar, a Ralph Lauren silk tie and leather wing tips by Fratelli Rossetti.” Ad nauseum, every other page. There are also numerous discussions among the characters over the niceties of dressing well: the proper color socks and belt to wear with a gray suit, what kind of tie knot to wear with a rounded collar, the rules for sporting pocket squares, and so on and so forth. At one point, referring to a fellow diner, Bateman asks Evelyn “Hasn’t it occurred to him that his suit might inspire loathing?” READ MORE >

April 25th, 2013 / 1:30 pm

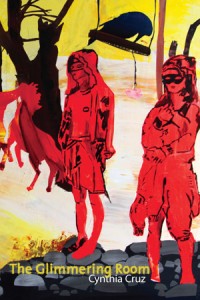

25 Points: The Glimmering Room

The Glimmering Room

The Glimmering Room

by Cynthia Cruz

Four Way Books, 2012

98 pages / $15.95 buy from Four Way Books or Amazon

1. “If you bring forth what is within you, what is

within you will save you. If you do not bring

forth what is within you, what is within you

will destroy you.”

—The Gospel of Thomas

2. When I picked up The Glimmering Room I was on a recent, incurably permanent Nine Inch Nails kick. I was listening to The Downward Spiral the minute the book came in, and kept it on for the entirety of the reading.

3. First poem “Kingdom of Dirt” places the material in the world of it’s prelude. The pages are almost hymnal in their design, with white space like musical score margins and titles in austere fonts, like stone engravings. The design works when you get partway through and see it set in deceptively clean and sterile rooms in a psychiatric hospital. It’s surprisingly quiet and deadly against the album playing in the foreground.

4. Like The Downward Spiral, there’s a concept in The Glimmering Room’s organization. I broke up the tracklist on YouTube so I’d force myself to stop and consider the poems, and to consider the album in individual pieces.

5. The thing is, this approach isn’t the primary consumer instruction of either work. There’s a narrative that runs through both, and The Glimmering Room is a concept book on contemporary hysteria much like The Downward Spiral is a concept album describing the descent of a person’s depression into their eventual suicide. Reznor described the album in interviews during the promotion of With Teeth as “friends that sound good next to each other.“

6. In the complete accident of getting the copy as I had this album on, I couldn’t bring myself turn the music. For one, the similarities of self-hatred in the book and the mental boil listening to those textures will make the room too thick to move.

7. And two, the contrast between noise volume of the two works is eerie. Cruz’s first few poems produced a psychological and somatic anxiety that I didn’t want to be left alone with the work, or else I might find myself on a dangerous line. Like I know I can’t drink and sit with The Downward Spiral’s last track in a melancholic mood without it disturbing me into holding a mirror up to myself in a sterile room.

8. The leotards, stuffed animals and tangible suitcases of baggage in The Glimmering Room’s anti-sterility play with the quietness of isolation, which is so intense against the heavy textures of The Downward Spiral that it mimics the lack of movement and external aggression of gendered isolation. While we can journal until oblivion, for a young adult woman, it’s not acceptable to get entropically and endogenously angry, while a young male enjoys the permission and romance of self-destruction anger.

Against the beautiful cover, their outward concerns with looks, the poems contain (apologies introducing the inevitable mad-lady malady cliché) Plathian stillness and resoluteness brightening fuss of blood-smeared text on a white wall.

9. “The traveling minstrel show

Called girlhood—

I burned it

Down to the ground:”

(“Eleven”)

The Downward Spiral was famously recorded at the site of the Tate-La Bianca murders, where “Death to Pigs” was smeared by Mason’s followers, in Tate’s blood, as a “witchy message.” Reznor’s told the story of Sharon Tate’s sister confronting him on a chance encounter during the rental, asking if he was exploiting the mythology of the site he chose. Afterwords, sick with himself, Reznor went back and cried that night, and the house was razed after the completion of the record. After touring, he returned to New Orleans and installed blackout glass in the windows of a funeral parlor in the French Quarter and stayed behind the gates.

10. Like Reznor’s penchant for American history in his material and mental rooms, Cruz doesn’t shirk the critical magnifying glass that details traditional hysteria-as-subject– it refrains from slipping into the bedlam tropes of post-Sexton confessionalism:

“Daddy, I am spit

Pasting junk and shit into glittering

Black pink pearls and beads of apathy.

Track down the pony

Trapped on the carnival-like barge

Lit in key lime green like a California

Ferris wheel to the Rhine,

Back to my Germany

Where this awful song began.

Give me back my Ritalin.

Give me my shock

Of medicine. Make sure my spine

Is still living. Mommy,

Slip the black eel

Back in the sealed aquarium.”

(“Strange Gospels”)

With the blunt diction and tonal speech, the work comes to us traceless of affect as an unmarked envelope, and her language is unrecycled, passing like a cult cinema scene on silent. READ MORE >

April 23rd, 2013 / 3:40 pm