I Don’t Know Should Matthew Savoca Get a Dog

HTMLGiant fave Matthew Savoca just came out with his novel yesterday, improbably titled I Don’t Know I Said. Laura van den Berg said it’s a book for anyone who has ever been bored. Michael Kimball said it’s got more charm than it should ever have. Scott McClanahan said it’s like eating baby food with a loved one. Chris Killen said he’d recommend it to anybody. The book is about Arthur and Carolina, youths in love, trying to do it right. Here’s an interview with Matthew, if you’re bored. On Friday evening Matthew will read the entire novel and broadcast it at Everyday Genius.

Hi Matthew.

Hi Sarah.

The Density at the Center of Everything: A Conversation with Erik Stinson

Erik Stinson is a writer of short fiction and poetry, an essayist, web artist and associate copywriter. I first met him outside a bar in Williamsburg in summer 2010. We skated that night and, later, both, separately, with Miles Ross. I asked him some questions about his life and forthcoming collection of stories, Tropic Midtown, which, like all of his books, he self-published and distributes.

HTMLGiant: You’re sitting at a desk, am I right?

Erik Stinson: Yeah.

HG: How’s the view from your desk right now?

ES: I can see out the window behind me, to a courtyard on the 5th floor, some light from 23rd street via a low building. Air rights etc.

HG: Okay, so you wrote a book called Tropic Midtown. It’s stories. What made you want to write these stories?

ES: I wanted to make certain memories, and unmake others. I guess I wanted to destroy some and shape others.

April 9th, 2013 / 10:29 am

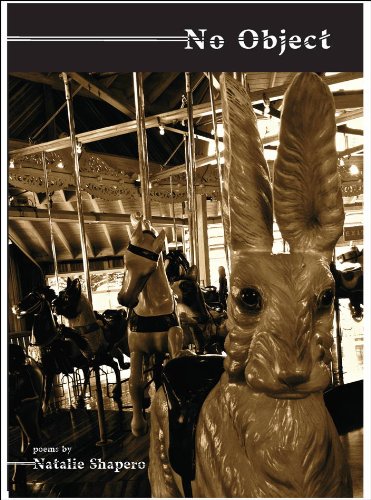

Natalie Shapero Talks with Rob Stephens About Her New Book NO OBJECT

Cue up the Boss, now, folks. Put on your best dancin’ kicks and turn out the lights. Recommended drink: Black Russian. Natalie Shapero, with her new book No Object, is about to walk on your computer screen and dish info about her poems, thievery, serrated stage knives, and other amazing platitudes.

I bought No Object in Boston, read it on the plane ride home, and knew I wanted to talk to Natalie about it. Thanks to Chris Higgs and HTMLGiant for giving me the forum to do so. Enjoy Natalie’s spitfire — I imagine you’ll be hearing her name a lot more in the future.

– Rob Stephens

April 3rd, 2013 / 11:32 am

Germs and Ideas: An Interview with Joshua Mohr

Josh Mohr‘s the author of a trio of fairly heavy duty fiction—Some Things that Meant the World to Me, Termite Parade, and Damascus, each of which was published by the fantastic Two Dollar Radio. They were published in ’09, ’10, and ’11, if years and chronology mean too much. The years those books were written and published in end up mattering, to a degree, given the following, which is an email interview with Mohr about his latest novel, Fight Song, out presently from Soft Skull Press. You’re welcome to note the fact that Mohr’s got a different publisher for this book than his three previous ones, and if you read/know Mohr’s stuff, you’ll note pretty quickly that Fight Song is a vastly different beast than any of his three previous ones (though an argument could be made about similarities, style-wise, with Damascus, but that’s for some other reviewer and venue). I don’t know how much more info’s pertinent to what follows, which is the transcript of a series of emailed questions and answers. As ever: you’re much better off reading the book than anything *about* the book or author, but we all need our cavemarkings and arrows.

– – –

I guess the first big question is: how did Fight Song get its start for you? I’m most curious about style, or tone. This one’s quite different from the earlier trio, and the difference reads/feels to me almost sum-uppable as: Saunders. There’s a sort of sort of hijinksy despair to this that reads, at least to me, as very like him. Where’d the tone come from for this?

My first three books all dealt with addicts and artists in the Mission District of San Francisco. I had great fun putting those books together, but I felt like I needed to push myself artistically—needed to completely dismantle my comfort zone. That’s when we do our best work as authors, when the potential to fail is at its greatest. I definitely could have written DAMASCUS 2.0, but what would be the point in that? I don’t want my career to resemble a glam metal band, just writing the same song over and over again. Plus, I don’t own very much spandex, I’m out of hairspray, and my cocaine days are in the rearview. READ MORE >

Donald Richie and the Japan Journals: A Tribute

Peter Tieryas Liu previously wrote about Donald Richie and his Japan Journals on HTMLGIANT (read the full review here).

And now this great video:

An Interview With Donald Ray Pollock

Several years ago I was about to board a plane to Virginia where I was to explore the campus of a school that would teach me to become a mortician. It’s since become a joke in various places that ‘I’m here, because my job as a mortician fell through…’ etc. Before boarding the plane, I grabbed a magazine—my memory eludes me as to which magazine it was, some cultural blah blah blah; something where books are mentioned—and during the two or so hour ride I read most of the magazine, finally rereading one portion over and over again.

Several years ago I was about to board a plane to Virginia where I was to explore the campus of a school that would teach me to become a mortician. It’s since become a joke in various places that ‘I’m here, because my job as a mortician fell through…’ etc. Before boarding the plane, I grabbed a magazine—my memory eludes me as to which magazine it was, some cultural blah blah blah; something where books are mentioned—and during the two or so hour ride I read most of the magazine, finally rereading one portion over and over again.

It was a blurb written about a novel called The Devil All the Time, with corresponding cover art featuring mangled marker-drawn crosses and skulls; and a glowing review from somebody somewhere. The writer’s name was Donald Ray Pollock, a name most people recognize along with the titles of his books nowadays.

Again, didn’t wind up becoming a mortician, but on that trip I stopped at a bookstore and picked up a copy of Pollock’s second book, reading it from cover-to-cover on the plane and car ride back to the middle of nowhere in Wisconsin; and for the first time in a long while I started to find romantic little moments along the barren roads beside our car, having Pollock’s eyes to see that you didn’t need New York to have literature, I guess, that sort of thing.

A month or so later I was cursing myself, finding out that Pollock’s first book, Knockemstiff, was sort of a prerequisite for the second—set as they both are in similar vistas of rural Ohio, where everything reeks of old death and strange blood. I picked up a paperback copy of his first as soon as I could and immediately set to reading it.

Both times, in similar and yet subtly different ways, I was floored. Knockemstiff reads as if Raymond Carver and Dennis Cooper had a kid and he lived down the street from Scott McClanahan; gloriously fucked-up images balanced against the monotony and odd sense of peace you get when you’re so far off the radar that you forget it even exists. This is Pollock’s coming out into the world of literature, and he does so with no shit-covered stone unturned. With his second, The Devil All the Time, it could be said that Pollock prolonged the sting of his previous short stories and the result is a portrait of American life nearly impossible to forget. The book opens with a father and son walking out to a small grove where they’ve been sacrificing animals, hoping for some kind of good fortune, and from then on it barrels headlong into a story spanning many years and veering off into these dirty cinematic takes on growing up, dealing with death, and out-and-out crime.

A Mountain City of Toad Splendor by Megan McShea

Yeah but come on, that’s the title of a book right there.

As Blake put it, it’s as if Megan studied at the Harvard for Ooh, and as Jeff Jackson said nicely, “You’re never sure what’s around the next comma.”

Lucy Corin said she remembers Megan’s dreams as if they were her own.

This book comes out today. It’s poetry and microfiction. It’s just $9 at PGP. And there are videos about it. Cool.

March 19th, 2013 / 8:37 am

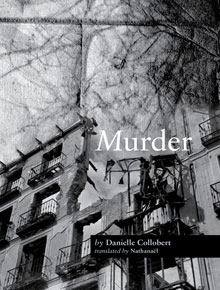

Murder: An Interview with Nathanaël, Translator of Danielle Collobert

Forthcoming from Litmus Press this April, Nathanaël’s definitive English translation of Danielle Collobert’s Murder marks the first ever of this French poet’s debut book. Originally begun in 1960 when Collobert was twenty years old, and published by Gallimard in 1964 under the auspices of Oulipo-founder, Raymond Queneau, this book laid the groundwork for what remains one of the most enigmatic and innovative bodies of work in contemporary French letters. As with the subsequent works of Collobert’s brief but impactful output, which lasted until her suicide in 1978, Murder speaks a language profoundly its own, unlike anything else she was to write, and quite possibly unlike anything else you may have read. Reading this prose gives one the rare impression of being in the presence of a voice speaking from the honest and cutting edge of present urgencies: that is, this is not a voice responding to conventions or trends in literary necessity, but one singularly engaging the emergent necessities of life itself, in all its complexity and danger. Here, in honor of Danielle Collobert and this fantastic new translation, Nathanaël and I discuss her life and legacy with an eye on her first work, Murder.

***

Murder

Murder

by Danielle Collobert / translated by Nathanaël

Litmus Press, April 2013

104 pages / $18 Buy from Litmus Press or SPD

Kit Schluter: To begin, what drew you to Danielle Collobert’s work? How did you discover it?

Nathanaël: I want to say that it was accidental, but I’m quite sure it wasn’t. Unless one understands friendship as accident. I entered, as did many, into Il donc, and Collobert’s Carnets, though with an eye turned away – perhaps out of a desire not to seek the life in the work, however much it is written there, and with such determinacy; the ‘twenty years of writing’ set against the impending suicide. Still, it is a hazard of hindsight to be able to set the life against the work, though this is so obviously a deformation of the reader, and so I resist as much as I can the tidy narrative of a life fallen from letters. The short answer to your first question is: Collobert’s language. But if the virtuosic remnants of Il donc are almost a perfect epitaph to the twenty years, I was much more viscerally and immediately impelled by Meurtre; I even borrowed an epigraph from this work into We Press Ourlseves Plainly much before the idea even of translating it had presented itself to me. Perhaps most immediately because of a shared concern, or conviction, that the distinction between murder and death is unconvincing and too readily upheld.

KS: What were the circumstances surrounding Danielle Collobert while she was composing Murder? Do you find that the book draws material or imagery from her experience?

N: My knowledge of Collobert’s biography is quite limited. Not unlike her parents and her aunt, who were all actively engaged in the Résistance during WWII, Collobert, a supporter of Algerian independence, was a member of the FLN (Algeria’s Front de libération national) at the time of Meurtre. She chose exile in Italy, where she completed work on the manuscript. It may be worth underscoring the importance of 1961, for the outcome of the war, which, in French contemporary society was never acknowledged under the name of anything other than the euphemistic “les évènements” (“the events” – to do otherwise would have been, not only to have acknowledged, if only semantically, Algeria’s nationhood, but the repressive force employed by France to resist – and as it happened, to defer – decolonization and independence). On October 17, 1961, a peaceful demonstration of many thousands of Algerians living in Paris, protesting the curfew imposed exclusively upon them, and the acts of police violence to which they were systematically subjected, was violently suppressed by Vichyist Maurice Papon’s police force, resulting in the arbitrary deportation of large numbers of Algerian demonstrators, and the summary execution of up to two hundred Algerians, many of whose bodies were pulled out of the Seine in the following days; several thousand Algerians were rounded up during the demonstration and distributed among prisons, the Palais des Sports and area hospitals. Several months later, on February 8th, 1962, what has come to be known as the Charonne Massacre took place at the eponymous Paris métro station; this demonstration, organized by the Left against the paramilitary OAS (the reactionary Organisation de l’armée secrète, which violently opposed Algerian independence), and often conflated in people’s memories (and in historical accounts) with the October massacre, resulted in the death of eight demonstrators at the Charonne métro station. It is not insignificant that French FLN supporter Jacques Panijel’s 1961 film, Octobre à Paris, which documents the moments before, during, and after the October demonstration, was censured by the French government and only shown for the first time in a French cinema in 2011 – half a century after it was made.

The photograph on the cover of Murder accounts, obliquely, and somewhat prochronistically, for these activities – it is a photograph of a bombed out building in Madrid, taken in 1937 by Robert Capa, during the Spanish Civil War.

Meurtre is tempered by the residues of such histories; but the work’s strength is in its ability to evoke them without resorting to explicit accounts, or naming. The generalization of historical violence is embedded in the intimate accounts presented to the reader – seemingly placeless, nameless, they nonetheless achieve historical exactitude through relentless repetition – a reiterative (mass) murder (one is tempted to say: execution), which afflicts and incriminates the gutted bodies that move painstakingly through these densely succinct pages.

7 cracks in the spleen cushion

23. Your Spirit Guide to Indie AWP.

1. New lit mag wants your words to glow: ‘pider.

2. Don’t forget about the Diagram Chapbook contest. Lots of $$, hipness, gravitas, and New Michigan Press makes a chapbook so lovely like large meadows/strobe light.

3. CreateSpace versus Lightning Source.

1. Henry Review video Q&A with Sam Lipsyte.

7. These aren’t new but this Lydia Davis interview and this Lydia Davis interview are damn good. I feel both the interviewer and interviewee respected the interview as a genre, as creating something.

10 point bulletin on David Shields

6. Good sex in literature is hard to find.

7. How much money do you take to AWP book fair? I take $100 in cash but not sure if that’s weak or strong or just OK.

Dance Around Like Meth Monkeys: A First Date Interview With Rauan Klassnik

Favorite color:

You have such gorgeous eyes!

Favorite food:

And such a brawny chest! And such expensive furnishings!

Favorite restaurant (besides Applebees):

Yeah, I admit it, I dated Adam for a while, but he was just way too demanding, physically, I mean. Always wanting me to act my book out on him. Really it was just too exhausting.

Favorite movie:

Do you live close by??

Favorite place in the world:

How much does your mother weigh? READ MORE >