A Field in England in the US

A Field in England is finally getting a US release, starting today. It was probably my favorite new film of 2013, and it certainly contained my favorite scene of 2013 (the tent scene—watch at your own risk!).

Drafthouse Films is releasing it in select cities (but not Chicago, boo, hiss). It’s also available for digital download.

I’ve seen this movie maybe four times already, and you better believe I’ll be watching it again. And somewhere I have a mess of notes on it that I keep meaning to type up into something semi-coherent…

R.I.P. Miklós Jancsó

The great Hungarian filmmaker Miklós Jancsó passed away on 31 Jan; he was 92 years old. (The New York Times obit is here.) I first learned about Jancsó from David Bordwell, who wrote a detailed analysis of the man’s 1969 film The Confrontation in Narration in the Fiction Film (some of which you can read here). That film has been difficult to find (though there’s an unsubbed copy at YouTube), but I was able to track down The Round-Up (1966); The Red and the White (1967); Elektra, My Love (1974); and what would quickly become one of my favorite films, Red Psalm (1972):

(Here‘s a detailed essay by Raymond Durgnat of that film.)

Jancsó is perhaps best known for his work in the late 60s and early 70s, which saw him systematically exploring the question of how few takes he could use to make a film, while simultaneously exploring how complex those takes could be in terms of staging. The 87-minute-long Red Psalm consists of 27 elaborately designed shots (see the above clip for an example); in this way, the film was a forerunner of Aleksandr Sokurov’s 2002 single-take feature Russian Ark, as well as Alfonso Cuarón’s recent Gravity. (Cuarón named Jancsó as his primary influence in this Empire interview). Fellow Hungarian Béla Tarr was also much influenced by the man’s work, and has called him “the greatest Hungarian director of all time.”

Despite Jancsó’s significant artistic achievements, he’s been unfairly overlooked by most US film distributors. But some of his work can be found both online and on disc. It’s well worth tracking down.

Let’s overanalyze to death … Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart”

So far in this very irregular series, we’ve scrutinized Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used to Know” and Macaulay Culkin eating a slice of pizza—preparation for tackling one of the greatest and most beguiling music videos ever made.

“Total Eclipse of the Heart” was a single from Bonnie Tyler’s fifth album, Faster Than the Speed of Night (1983), and her biggest hit. It was written by Jim Steinman, Meat Loaf’s once and future collaborator. Steinman also planned out the video, which was then directed by Russell Mulcahy, a man responsible for numerous ’70s and ’80s music videos, as well as the films Highlander, Highlander II: The Quickening, and Blue Ice. So that’s the aesthetic world we’re dwelling in. (In a single word: overblown.)

The video itself is pretty broad, and rather easy to read—broadly. Simply put, Tyler plays an instructor (or an administrator) at an all-boys boarding school. (I will refer to her character as “Tyler” throughout, for convenience’ sake.) Extremely sexually repressed, Tyler endures a long night of the soul fantasizing about her young charges; this constitutes the bulk of the video. Come morning, she (and we) are returned to restrained, repressive reality. But we’re left with the hint that A.) at least one of her students has magically become aware of her fantasy, or B.) her fantasia has caused Tyler to become mentally unhinged. (I lean toward B and will defend that reading below.)

That’s the basic outline. The devil, however, sits in a straight-backed chair, clutching a dove. He’s also in the details, so let’s delve deeper …

Let’s overanalyze to death … Macaulay Culkin eating a slice of pizza

On 16 December of last year, Macaulay Culkin posted to YouTube a video of himself eating a slice of pizza:

I watched it and showed it to some friends because, on the one hand, how random! Macaulay Culkin! Eating pizza! Lol! One million other people and counting apparently felt similarly.

The video fascinates because it depicts a star (or a former child star) doing something utterly mundane. The presentation is simple, stripped down. The shot is static and there are no cuts. Culkin looks embarrassed to even be there, to be watched eating. There’s no glitz, no glamor. The guy eats pizza just like you and me, even tearing off the crust (though I would’ve finished the rest of the slice).

At the same time, the video fascinates because it’s awful—it’s “so bad it’s good.” That reaction is breathlessly conveyed in the Time Magazine blog post, “Questions We Asked Ourselves While Watching Macaulay Culkin Eat a Slice of Pizza,” which presents no fewer than forty-six questions about the video, in pseudo-live-blogging fashion:

Why does he look like he really doesn’t want to be wherever he is, or eating the slice?

Has he ever eaten a slice of pizza before?

Why does he look so sad?

Does he know he’s being filmed?

Do the pizza oils get trapped in his beard?

Why does he keep looking up?

Forty-six questions is a lot of questions, prompting a forty-seventh: “How many times did author Eric Dodds watch the damn thing?” And one million views is a lot of views. Thus, despite being banal, despite being awful, the video is somehow also something else. Would it be fair to call it transcendent? Even sublime? And if so, why? Because it purportedly offers us unmediated access to a former star, now desperately embarrassing himself?

But far from being random, or mundane, or excruciatingly candid, Culkin’s pizza video is a put-on, its every second pure artifice. For starters, it’s a loving recreation of another work—a short film of Andy Warhol eating a hamburger:

Dawson’s Creek Seasons 1-6 Netflix 2013 Cut

I should say that I’d never seen a full episode of Dawson’s Creek until 2013. This surprised my girlfriend Jackie, so she encouraged me to watch the series. Growing up, I wasn’t allowed to watch commercial network TV. I didn’t really start watching primetime soaps until early high school. Before that, I was only interested in The Sci-Fi Channel.

Maybe I was expecting something a lot more expansive, and a lot less safe? I was expecting The OC plus grunge plus Boston. What I got was Boston minus grunge.

Dawson himself looms largest in a full Netflix viewing of the series. His very personal, very idealized type of optimism bleeds over and across the typically 3-5 plot lines that run between and within each episode. Constantly craving a pure articulation of his artistic vision that could merge effortlessly with his romantic inner-life, he almost always fails to live in reality. His over-greased wide-angle-lens-POV on his hometown of “Capeside” Massachusetts, and particularly its high school experience, becomes charmingly narcissistic.

It is an old, mellow form of mass-culture narcissism. I sip video cuts to form a smooth, rich blend of teen longing, the residue of good parenting, and the nearly raceless, nearly classes, nearly Internet-less painting of a total herb who came-of-age in a 1990s New England TV land.

Meta-naivete. This is the best feature of the show. The slowness, the tween-camp and the scripts that seem to lay open the inner guts of the 1990s TV studio production mechanics.

The show is about a boy. And the boy seems to know that his life is worth being made into a show. The show supports this theory by continuing to be about him, long after the viewer has become exhausted by whatever small intricacies of character have been pummeled to meaninglessness sludge by endless waves of episodic plot.

And of course, Dawson is a young filmmaker, soaking in sappy meta narrative puddles. This plot ramps up slowly as high school ends and his directing career begins to take off.

His favorite director, stated repeatedly, is Steven Spielberg.

Dawson is not an interesting guy. He thrives under these odd, broad narrative circumstances. We, the 2013 adult audience of a vintage teen mass-media soap, are critically aware that this guy doesn’t deserve to be the center of the show, but, having maybe grown up in the 90s, also vaguely crave the easygoing jr executive male phallocentrism of Dawson’s bumbling tonality. He’s the harmless young hegemony we all looked to in our teen and pre-teen years. The tall handsome thinker. The class frown. His success isn’t surprising or remarkable, in the same way that the mega-success of an ensemble teen drama that slightly pre-dates the coming-of-age years of the millennials/echo boomers is almost destined to be. Huge audience. Mass-televised puberty.

Dawson: perhaps a very MTV form of pre-internet and early internet self-awareness, perhaps just a single character written for a booming tv teen audience, the size of which (proportion of total media mix on Wednesday nights during the school year?) may never be seen again.

Another series, The OC, was dramatically more artful and blissfully less New England. Having only lived on the East Coast for a few years, I’d venture to say Hollywood numbs the aesthetic and cultural disagreements between the eastern and western US, frequently casting brooding jews in California and bleached out surfers in Manhattan. The OC kind of blew up that balancing strategy to give California a naturalist primetime TV treatment. I watch The OC as a glossier, grittier, less-boring teen drama, aided greatly by an escape from the eastern (almost… bleakly European…? with a different orientation of class) middle-American malaise and successfully existing in the alien seascape-soundstage of Southern California dreams, a narrative location that Dawson’s Creek never tries to achieve, even as characters live briefly in Los Angeles.

Imagine dumpy, close interiors shot with old lenses, recorded on to worn magnetic tapes. Underwhelming vistas of what is supposed to look like coastal New England but is clearly someplace–a cheaper location–in the Carolinas. I guess what I’m trying to say is that Dawson’s Creek feels chained to some kind of older television convention, something sort of cheesy and safe, that The OC manages to shake off, for the better. Leave it to Dawson, I love Joey, The Capeside Bunch.

In addition to being trapped in greater-Boston-via-TV culturezone and within Dawson’s bland masculine show-running character, the tension of show rarely moves beyond the Dawson-Joey-Pacey love triangle. This triangle traps everything. Characters outside the triangle are vastly more insightful. The three other prominent roles make up maybe a third of underlying plot cycles, but are present in a much greater percentage of the really enjoyable scenes.

I guess.. even the designed-to-be-overlooked Pacey sometimes becomes interesting, in terms of his class position, especially. Dawson and Joey, the couple who are central in the first season, really paint a picture of zero personal growth. They, like a certain percentage of every generation, become trapped in a view of the world that pre-dates high school. They are barely-dynamic characters who, rather than learning something about themselves, just get older.

Joey, Dawson’s main love interest who evolves from a foil into the queen of her own universe of sappy, solopsistic femininity, is a huge problem for the show in terms of watchability. Her level of discomfort with nearly everything pushes the show slowly forward into the abyss of… longing for an ideal life that she never bothers to fully articulate? She wants everyone to read her mind and know what she wants before she does. Inexplicably (via the magic of TV writing), the entire world falls at her feet, begging for her affection.

She has almost no female friends.

She is an unrelenting downer, which is sometimes entertaining, but frequently just frustrating. She’s constantly running away from the present. But unlike Dawson, she apparently does this for personal rather than vocational reasons? Dawson has a dream and she has a choice to make between two high school suitors. Indecision, anxiety, a delusional work ethic. The big thing she wants in her life is to visit Paris, which she actually fails to do, initially – as if a single vacation could be a life’s goal. That’s basically what she has: a vague, unambitious desire to be a ‘study abroad’ person. The writers could have done a lot better.

I’m glad that I’ve finished the series. Jackie and I agreed that watching the whole thing probably wasn’t worth it. The first three episodes and the last three would suffice.

On a final negative note, on Netflix the entire series except the final two episodes features a replacement opening theme song. It goes something like “Heat is in the sky / head is on the ground / feet are in the air / my life is turning around… voice inside my head / telling me to run like mad…” it’s fucking awful. I assume that the Netflix-rights sale didn’t include or couldn’t afford the rights to a lot of the original music. The series would have been more entertaining with the original pop songs.

December 20th, 2013 / 11:38 am

My Top Five Films of 2013

Center Rest

(Dir. Antonio Johns)

I saw this on a train. I was traveling from Seattle to Portland by train, and the person sitting next to me asked me if I wanted to watch a movie with him. READ MORE >

My favorite films of 2013 so far & still in progress

This year, I tried to get caught back up on films. And even though 2013 is far from over, here are my favorites so far:

- A Field in England (Ben Wheatley & Amy Jump)

- Blue Jasmine (Woody Allen)

- Gravity (Alfonso Cuarón & Jonas Cuarón)

- Iron Man Three (Shane Black & Drew Pearce)

- Le joli mai (Chris Marker; revival)

- Museum Hours (Jem Cohen)

- Only God Forgives (Nicolas Winding Refn)

- Prince Avalanche (David Gordon Green, + here’s hoping Paul Rudd is Ant-Man)

- Seven Psychopaths (Martin McDonagh—technically 2012, but I didn’t catch it until this year)

- The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson; ditto)

- The World’s End (Edgar Wright)

- Upstream Color (Shane Carruth)

I have plans to write more about 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 12. As well as 9, perhaps. (But not 10.)

+: Godard’s Le mépris is getting a 50th anniversary release, and of course it’s incredible, even though I’m going to miss it this week at the Siskel because I’m stuck grading final papers.

Other new films I’ve seen and enjoyed to varying degrees:

25 Points: 12 Years a Slave’s Glaring Flaws Won’t Deny It A Oscar — (Django Unchained Also Discussed)

1) Django Unchained is a “better” movie than 12 Years a Slave.

2) Harold Blood, Samuel L. Jackson (Stephen), and Brad Pitt (Bass): these three form the bedrock of the most original part of my argument. Force of character. Force of personality. (I’ll talk more about this later on).

3) The next part of my argument resides in “excitement”. In aesthetic pleasure. Yes, there’s something pleasing and thrilling about Tarantino’s excesses and indulgences, his operatic screams. And there’s something pleasing, immensely pleasing, about his success in creating a Western (a spaghetti Western) within a Slavery landscape because, well, that’s no easy task.

(and, plz, here let me point out that “Best Picture” does not mean “Most Necessary Picture”)

4) And the most important part of my argument is that 12 Years a Slave, though flawed, has become a kind of Sacred Cow and, thus, tends to get a free pass since it is so “necessary” (which it is, since “Americans tend to have amnesia about historical events*” and in the case of Slavery and all its horrors the amnesia is compounded by “deep trauma*”). So, because the movie is a valuable and needed wake-up call we can and need to kind of sweep its problems under the rug:

12 Years a Slave has some of the awkwardness and inauthenticity of a foreign-made film about the United States. The dialogue of the Washington, D.C., slave traders sounds as if it were written for “Lord of the Rings.” White plantation workers speak in standard redneck cliches. And yet the ways in which this film is true are much more important than the ways it’s false. (Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle)

5) The quotes starred (*) above are from a TIME interview with Henry Louis Gates Jr. This interview’s a decent quick-bite read, but much more valuable and meaty is Gates’ interview with Tarantino (you can find it here on The Root) which is a wonderful series of insights into Tarantino’s intentions as well as Gates’ opinion of Tarantino’s accomplishments in what Gates calls “the best postmodern take on Slavery*.”

(* this last quote, again, is from the Time interview in which Gates also hails 12 Years a Slave as “the most realistic account of Slavery”).

6) An important and necessary movie, again, of course, isn’t necessarily the best movie, but here are some quotes from Anthony Stokes’ “On How 12 Years a Slave Succeeded where Django Unchained failed”

“with a matter as serious as slavery you should have more respect.”

November 25th, 2013 / 4:21 pm

Notes on Satantango (the Book and the Film) – Part 1/3

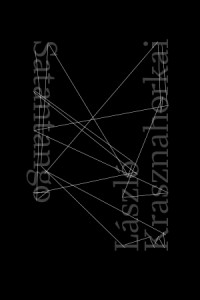

Satantango

Satantango

by László Krasznahorkai

Translated by George Szirtes

New Directions, 2012

288 pages / $25.95 Buy from New Directions or Amazon

&

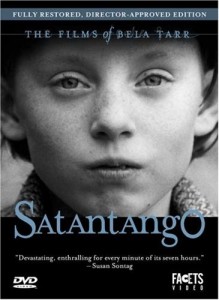

Satantango

Satantango

Directed by Béla Tarr

Screenplay by Lászlo Krasznahorkai

DVD: Facets Video, 2008

435 minutes / Available on Amazon

Released in Hungarian in 1985, Satantango, László Krasznahorkai’s first book, was translated into English only last year. Published by New Directions, the novel displays the melancholy, bleakness, and long sentences that define Krasznahorkai’s other books (War & War, The Melancholy of Resistance, etc.).

Krasznahorkai’s collaborator and fellow apocalypse maker Béla Tarr adapted the 288-page novel into a seven-hour film in 1994. Because of the duration between the appearance of the film and the publication of the English translation, we (like most) had watched Tarr’s adaptation long before reading its antecedent. This reversal of the traditional adaptation-viewing chronology (in addition to Krasznahorkai’s role as screenwriter) makes it difficult to think of the novel independent of the film. But despite the convergence of the two forms of Satantango, we do not believe the demands of the long take are the same as those of the long sentence.

What follows is a collection of take-by-take notes on disc one of the film and the corresponding passages of the novel. (Notes on discs two and three are forthcoming.) Our time stamps are based on the Facets Satantango DVD (2008). Throughout the notes, we acknowledge differences between the novel’s content and the film’s content, as well as translation differences between the novel and the DVD’s subtitles.

***

We see a cow emerge from behind the building, nothing in front of him but a vast scene of thick mud with glimmering streaks of wetness that resemble the trails that snails make when they zigzag across dark pavement. One cow becomes many, and they slowly make their way together. No one leads them or chases them but they seem to know their way. They take their time. They have, it seems, all the time in the world. One even pauses to mount another. This scene, though absent from the novel, sets a haunting tone of obliteration for the film. We watch the cows, then continue to watch, continue to watch past the time of watching, past the time of a simple a gaze or witnessing, look at them for so long that when the camera finally moves away from the herd of animals and pans past the dilapidated buildings, the mundane and bleak textures, the strange marks and letters, the utter signs of disintegration and decay become for us a relief. The wind howls and it feels like silence, yet it is not silent. We can hear the cows’ feet move through the mud, the mooing; the sounds are almost daunting, eerie. Without music (we keep waiting for it, hoping it will come to shake us out of the strange unreal reality of this scene, random sounds that seem to anticipate some cohesive and introductory soundtrack), the scene is discomforting but mesmerizing. Here, inside the muddy world we have found ourselves in, we learn to wait.

[1:35–9:06 / not in novel]

In voiceover:

“One October morning before the first drops of the long autumn rains, which turn tracks into bog, which cut the town off, which fell on parched soil, Futaki was awakened by the sound of bells.” (Satantango, film)

“One morning near the end of October not long before the first drops of the mercilessly long autumn rains began to fall on the cracked and saline soil on the western side of the estate (later the stinking yellow sea of mud would render footpaths impassable and put the town too beyond reach) Futaki woke to hear bells.” (Satantango, novel, page 3)

[9:06–9:50 / page 3]

THE NEWS IS THEY ARE COMING / NEWS OF THEIR COMING

We become complicit in anticipating THEM.

[9:50–9:58 / page 3]

There’s a window centered at the top of the frame. We can hear a sort of musical drone and subtle bells as the room and window grow brighter. At 11:15, there’s off-screen noise—the sound of Futaki removing bed sheets, we surmise. (Note that there’s no clock sound yet.) We come to consciousness with Futaki as he stands and limps to the window at 11:40. He’s wearing a sleeveless shirt and shorts. The room, a kitchen, is now visible. The sound stops, and Futaki comes back toward the camera. The ringing starts up again and he returns to the window. It stops once more and Futaki comes back to the bed. (In the novel, this scene contains a penetrating intrusion into Futaki’s thoughts.) “What is it?” asks Mrs. Schmidt, beginning the film’s first dialogue. Futaki tells her to go to sleep, then says he’ll “pick up [his] share tonight” or the following day.

[9:58–14:17 / page 4]

The camera has turned 45 degrees to the right, facing a small fridge and another table. Shod with laceless high-tops, Mrs. Schmidt crosses the frame from right to left. She moves almost out of frame to take a rag from the door; then she comes toward the camera, raises her nightdress, and squats over a pan. No face. Her head is on her left knee. She splashes water up at her crotch and then stands to wipe with the towel. She exits at left. A fly comes into frame. In the novel, Mrs. Schmidt is a sour-smelling woman. In the film, we have instead this sour-looking image of her. It’s significant that this scene comes so early in the film: an introduction to a quotidian perdition.

[14:17–15:33 / not in novel]

Mrs. Schmidt’s back is to the camera. She’s sitting at the table/window among a collision of patterns: wallpaper, curtains, table cloth, seat cushions, bureau cloth. Off screen (from bed), Futaki asks her, “You had a bad dream?” At 15:42, the fly appears on the seat cushion, hums.

Her dream: “…he was shouting…couldn’t make out what…I had no voice…. Then Mrs. Halics looks in, grinning…she disappeared…. He kept kicking the door… In crashed the door…. Suddenly he was lying under the kitchen table…. Then the ground moved under my feet….”

Futaki’s reply: “I was awakened by bells.”

Alarmed, Mrs. Schmidt looks over her left shoulder and asks, “Where? Here?”

“They tolled twice,” says Futaki.

“We’ll go mad in the end.”

“No,” says Futaki. “I’m sure something’s going to happen today.” (Our introduction to the anticipation that’s central to Satantango.) Does Mrs. Schmidt smile at this?

Like the bells that Futaki hears, Mrs. Schmidt’s dream is proleptic: Schmidt comes to the door, and Futaki shuffles off.

[15:33–17:50 / pages 6–7]

Though the density of text in the novel (there are no paragraph breaks) creates a lack of a clear hierarchy of action or language, in the film we follow the camera’s cue, the camera’s gaze. As Futaki hides in the other room, we stay on his side of the door. A mini-drama unfolds on the other side, but we are prevented from being invested in that. Or at least our distance from the scene doesn’t allow for that kind of emotional complacency, at least not yet. We wait with Futaki. Even after Futaki enters the other side to retrieve his cane and exists for a moment in that other space, currently inaccessible to us, the camera chooses to linger here. The indifference of the scene, the door, the camera. Then, with the waiting, the textures of the wallpaper and curtains starts to take on a strange form, as when you stare at a word too long and it begins to morph into something unnatural.

[17:50–20:10 / page 7–8]

There is the strange frantic hurriedness in the novel as Futaki internally exclaims about the temporary intruder (though perhaps it is arguable who is the intruder in any particular situation), “He’s going to take a leak!” In the film we are a silent observer of Futaki silently observing Mr. Schmidt taking a leak outside in the now very familiar Beckettian mud.

[20:10–21:34 / page 8]

November 25th, 2013 / 12:24 pm

Some movie news plus videos to look at

1. Peter Greenaway and Jean-Luc Godard have made a 3D omnibus film (along with one Edgar Pêra). The 2D trailer is here, and you can find information online: CinemaScope / Fandor / The Hollywood Reporter / Mubi / Variety.

2. Guy Maddin is planning a moving-picture adaptation of Sparks’s radio drama / concept album / opera-thingy The Seduction of Ingmar Bergman.

3. A lot of people don’t know that David Lynch once made a video for Sparks, but you’re not one of them:

And this is also relevant.

4. While we’re all here, we might as well look at this.

5. As well as this. Pretty well-done, no?