On Kinfolk

The journal that makes me feel the worst about my life is Kinfolk. It’s beautifully designed with a sharp, clean aesthetic, and its contents—for creative professionals concerning home, work, style and culture—seem earnest and helpful enough, if not a touch self-involved. I guess modern chic or yuppie hipster would describe their vibe. Whenever I see an issue at the bookstore, the first thing I do is smell it, fanning a gentle breeze on my nose. Then I allow myself a quick gander until I feel like killing myself. Then I put it back on the shelf with this increasing suspicion that the white people have won.

Call for Submission: A Shadow Map/An Anthology By Survivors of Sexual Assault

In this dumpster fire of an election year in the United States we have heard a lot of dangerous #rapeculture rhetoric from Donald Trump. After Trump’s “grab them by the pussy” statement, writer Kelly Oxford responded on Twitter, putting a solicitation out for people to name their first sexual assaults (which certainly are/were probably not their last). Read the NPR article HERE. The response to her call was/is overwhelming, staggering, heartbreaking, and not in the least surprising to other folks who have also had these experiences and/or are aware of every facet of this culture. As Oxford stated in her tweets, these stories are not just dry, dead statistics, these stories are true, horrifying, and all too common. This is a reality for so many people.

In a poignant and much needed call for submissions, Joanna C. Valente, the new Managing Editor of Civil Coping Mechanisms, is editing an anthology called A Shadow Map: an Anthology by Survivors of Sexual Assault, to be published in February 2017 by Civil Coping Mechanisms.

Here are some words from Valente and CCM: READ MORE >

Dikembe Press has a cool name and they’re reading chapbook manuscripts

If Dikembe Mutombo decided to write a chapbook-length manuscript of poems about what it felt like to be one of those weird Internet Era cultural figures who has a sugar-rush style identity and factors thus accordingly into evil surreal advertising memes, he would probably just use his giant arms to place his chapbook manuscript into Dikembe Press‘s electronic mail inbox.

If Dikembe Mutombo decided to write a chapbook-length manuscript of poems about what it felt like to be one of those weird Internet Era cultural figures who has a sugar-rush style identity and factors thus accordingly into evil surreal advertising memes, he would probably just use his giant arms to place his chapbook manuscript into Dikembe Press‘s electronic mail inbox.

But you’re not Dikembe Mutombo. You’re not in any commercials. Write a good chapbook manuscript and send it to Dikembe Press. They’re reading manuscripts for a month. The guy Jeff? He’s from Reno. They make good chapbooks.

If any of us really had imaginatively big arms, they would put us in a tiny cell in the White House basement and the Vice President would laugh at us and light matches against our skin.

Send your chapbook manuscript to Dikembe Press.

May 27th, 2014 / 2:48 pm

WHAT BOX? Talking with Lance Olsen on FC2’s 40th Birthday

Founded in 1974, FC2 is one of America’s best-known ongoing literary experiments and progressive art communities. In honor of FC2’s fortieth birthday, publisher Lance Olsen has generously answered the following questions about publishing, longevity, and innovation.

***

Rachel: What is FC2?

Lance: FC2—short for Fiction Collective Two—is a small, independent, not-for-profit press run by and for innovative authors. One of America’s best-known ongoing literary experiments and progressive art communities, for the last 40 years FC2 has dedicated itself to bringing out work too challenging or heterodox for the commercial milieu. Originally founded in 1974 as Fiction Collective by a handful of writers—Ronald Sukenick, Raymond Federman, and Jonathan Baumbach among them—FC2 has so far published more than 200 books by more than 100 authors.

Rachel: What does FC2 mean to you?

Lance: FC2 is an ongoing investigation into what innovative writing means—and that meaning is continuously in flux. One of the great joys for me about our editorial meetings, which take place once or twice in the fall, and once or twice in the spring, is that they make up an ongoing conversation about such troubled and troubling terms as “cutting-edge,” “artistically adventurous,” and “experimental.”

Those terms mean something else now than they did in, say, 1974; will mean something next Tuesday than they did last Monday; will mean something different to one person than to another—which is to say such terms are inherently unstable ones, open to ongoing modification, depending on who you are, where you are, what you’ve read, and so on. That is, they are terms always-already in-process.

By my lights, at the heart of them are a series of implied questions: what is narrative? what are its assumptions? what are its politics and social dynamics? its limits? how does narrative engage with the problematics of representation? identity? temporality? gender? genre? ideas of “literature” and “the literary”? authorship? readership and the act of reading in the twenty-first century?

In other words, perhaps a fruitful way of approaching a tentative definition of such narrativity—represented with respect to FC2 by such diverse authors as Lucy Corin and Brian Evenson, Cris Mazza and Amelia Gray, Michael Martone and Stephen Graham Jones, Matt Kirkpatrick and Samuel R. Delany, Michael Joyce and Clarence Major, Vanessa Place and Hilary Plum, Joanna Ruocco and Leslie Scalapino, Melanie Rae Thon and Yuriy Tarnawsky, Steve Katz and Mac Wellman, Diane Williams and Lidia Yuknavitch—might be to suggest it is the sort that includes a self-reflective awareness of and engagement with theoretical inquiry, concerns, and obsessions.

Two Lines Press: Interview w/ Scott Esposito

HTMLGIANT recently featured a review of The Fata Morgana Books by Jonathan Littell, published by the fantastic Two Lines Press that is bringing some splendid international works into English. I had a chance to ask Scott Esposito some questions about the press.

***

Janice Lee: What is Two Lines Press and what sets it apart from other publishing projects?

Scott Esposito: Two Lines Press is a nonprofit publisher of exclusively literature in translation. We’re akin to a number of nonprofit translation publishers (e.g Archipelago Press, Open Letter Books), but I think there are a few things that set us apart.

First off, I’m not aware of anything like us in the San Francisco Bay Area (where we’re headquartered), which I think is significant. We do a number of events in the community each year, and we’re in contact with some of the best local bookstores. I think it’s an important thing to have a press like us pushing the translation line around these parts.

We also have a journal of translation (in addition to publishing books) called TWO LINES, not something that most translation presses can boast. For 20 years has been published annually, and starting in Fall 2014 it will publish twice-yearly. The journal has worked with a lot of the best people in translation, and I do think it’s a pretty special thing to have on with us.

Then there’s the fact of our literary aesthetic. Most translation-only presses are such small, intimate operations that the prejudices of the staff and their tight circle of translation friends really shines through. I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to say that we have our own particular take on what constitutes “great literature.”

And maybe one more thing: we have our own podcast called That Other Word that I cohost with the incredible Daniel Medin of the Center for Writers and Translators at American University in Paris. We do a 15-minute segment of new translation recommendations and then a 45-minute interview with a translation professional. Past guests have included Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Lorin Stein (of The Paris Review and FSG), Ethan Nosowsky (of Graywolf), Sylvia Whitman (of Shakespeare & Co in Paris), Margaret Jull Costa, Petra Hardt (of Suhrkamp).

JL: It seems that there’s been a renewed interest in translated works in recent years and more publishers concentrating on bringing more unknown works to the US. Does this seem to be the case for you? And if so, why do you think this is?

SE: It’s possible—Chad Post tracks the number of fiction translations published each year, and the number has been increasing over the past few years. Although, it is hard to tell if this is a trend or an aberration right now. (For instance, that number was bumped up significantly by the creation of AmazonCrossing, which accounted for nearly 10% of the total in 2012, but those books were largely horrible titles that have no literary value, and it looks like Amazon is now backing off of publishing.)

But definitely there is more of a conversation around translation, and more of a sense of shared mission and solidarity among the people in the community. You can ascribe some of that to the community-building enabled by Internet technologies, and initiatives like the PEN World Voices Festival or the Best Translated Book Award.

But, in my opinion, the most significant reason for any renewed interest in translation is because this is where a lot of the literary innovation is occurring these days. There are kinds of fiction available in translation that are simply not produced here in the U.S. When I think of titles like Blinding by Mircea Cartarescu, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle sextet, the work of Roberto Bolaño, Hilda Hirst, Laszlo Krasznahorkai, just to name just a few recent examples, it’s very clear to me that fiction like that is not being written by American writers.

As serious writers and readers here in the U.S. have become interested in having new experiences and expanding their artistic horizons, I think it’s been a very natural thing to look abroad for new influences.

SE: For me, the biggest pleasure is the privilege of being among the first to read some of the best of the best literature from all around the world. Editing at a translation press is like having people hand-pick the very best books they can find from all over the globe and then deliver them to you. That’s an amazing position to be in.

One thing that’s both a challenge and a pleasure is working with translators. It’s a pleasure in the sense that translators are some of the most articulate, knowledgeable, passionate book people I’ve ever met. Getting to correspond with them daily and hang out with them at conferences and such is such a treat, and it’s made me a far better reader, writer, and person. Working with them is a challenge in the sense that you have to develop a different set of editorial practices in order to work with a translator, as opposed to directly with the author. It can be tricky to edit and evaluate something when you’re actually reading someone’s interpretation of an original text. This is even more of a challenge when you consider that in translation there is never any “right” answer—on each page you are forced to choose the best compromise among a host of options with their own pros and cons.

The other challenge is strictly practical: translations come with their own particular expenses, we’re often reliant on readers to report on books for us, and, despite gains, it still is hard to market translations and get press attention for them. All of that makes it a lot harder to stay above water (one of the reasons we are a nonprofit).

SE: As a huge fan of Laszlo Krasznahorkai, I can’t help but anticipate another Krasznahorkai title that Ottilie Mulzet is working on right now (she’s the one who did that incredible, incredible translation of Seiobo that just came out this fall). It’s called Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens and it will be appearing with Seagull Books, one of the most interesting translation presses to come on the scene in recent years. For a preview of this title, you can read more about it in Issue 2 of the journal Music & Literature. (I’m also pretty sure Ottilie discusses it in an interview I conduct with her in the same issue. If not, read it anyway—her discussion of Krasznahorkai’s career should be a no-brainer for any fan of his work.)

Open Letter is set to publish two books by the Chilean author Carlos Labbé: Navidad & Matanza and Locuela. I’ve read the latter in Spanish and the former in English, and I think Labbé has huge potential to be one of the best recent discoveries from Latin America.

NYRB Classics is doing this giant selection of Balzac’s short stories, which I am hugely excited about. I am an unabashed Balzac fanatic, a person who thinks every creative writing student in the country should read his best work and try their best to achieve even 1/8th of his magnificence. Any time I see a Balzac translation that I do not own, I immediately buy it, and then I read it. So 400 pages of mostly untranslated stuff is a blessing.

As a big fan of Edouard Levé, I’m excited to see that Dalkey Archive is publishing his Works in 2014. This title consists of a list of his potential literary projects. And there is also Melancholy II by Jon Fosse. The first volume of Melancholy was one of the darkest, toughest, most Bernhardian texts I read in 2013.

My colleague CJ Evans adds that he’s excited about the Henrik Nordbrandt title When We Leave Each Other forthcoming from Open Letter Books. He’s also looking forward to Grzegorz Wróblewski’s Kopenhaga, forthcoming from Zephyr.

SE: Of course! Next year we are doing a remarkable book called Baboon by one of Denmark’s leading authors, Naja Marie Aidt. It’s a series of utterly bizarre short fictions, each of which just keeps accelerating until it achieves this kind of demented headlong force. Reading the book as a whole is kinda amazing. As I read each fiction sequentially, my eyebrows kept raising higher and higher until I think I strained a muscle. She really achieves this strange aesthetic territory that is wholly her own, insofar as I can tell.

Then after that we are doing this book called Self-Portrait in Green by Marie NDiaye, which is a completely absurd “memoir.” NDiaye claims that this book is about herself, but it has dead women roaming around it, all these “women in green” who keep popping up and freakishly menacing her, a section where she visits her estranged father in Africa that I’m still not totally sure whether is a dream or not. It’s a really crazy, extraordinarily well-written (and extraordinarily well-translated) re-imagining of what a memoir is.

SE: I guess I’d just like to say that if you are one of those people who loves translation and loves the presses that publish translation, then take a moment right now to purchase a subscription to one of them. I can’t tell you how happy you will make that press. As a publisher, subscriptions are just about the best thing ever. Not only is it great to know that readers put that much trust in our editorial vision, but it’s also really, really helpful on a purely practical level: knowing that we have a list of people who have already signed on to purchase our books no matter what really frees us up to not think about sales to such a large extent and to do the really risky projects. So whether it’s us or Archipelago or Open Letter or And Other Stories or whomever, get that subscription.

Scott Esposito is the co-author of The End of Oulipo? (Zero Books, 2013) His work has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, The White Review, Bookforum, The Washington Post, The Believer, Tin House, The American Reader, Music & Literature, and numerous others. He edits The Quarterly Conversation and is a Senior Editor with TWO LINES.

December 10th, 2013 / 11:35 am

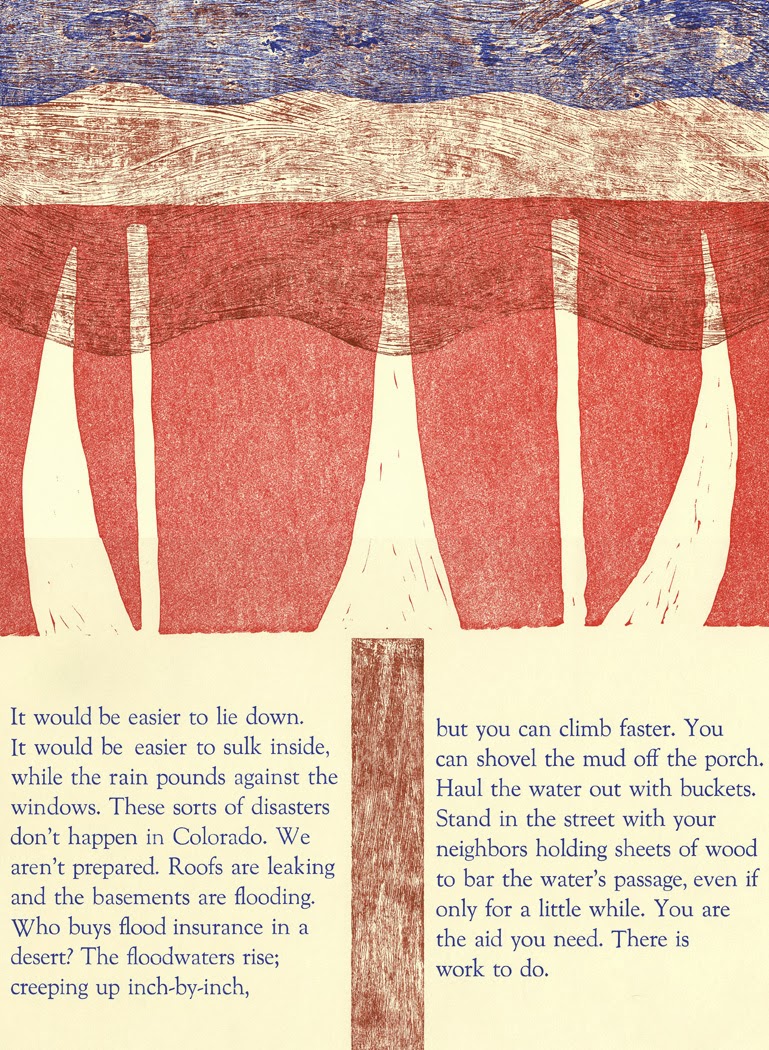

Flood Relief

There was a flood in Colorado and NewLights Press, which specializes in high-quality handmade books, is giving all the money they make this weekend to help fix things. Their books are beautiful. You should check it out.

Two Releases From Unlikely Books

Unlikely Books had two new releases in September, We’ll See Who Seduces Whom, with poetry by geniu-maniac wordsmith Tom Bradley, and truly twisted art by David Aronson; and Pleth, with textual poetry by Marthe Reed and artfully composed poetry cells by j/j hastain. Unlikely, which has been around as an online journal since 1998, began publishing books in 2005. After a relocation to Louisiana by Publisher Jonathan Penton in 2010, and a reevaluation of the current and upcoming publishing markets, neo-pulp online journal Unlikely has come back as Unlikely Stories: Episode IV, bigger and badder than ever, rebranding itself as a champion of transgressive literature.

Bizarro writer, political gadfly, prodigious poet Tom Bradley has done it again, once more turning the improbable into the compelling, showing us why he’s the guy mainstream writers wish they had the guts to be. This time, he goes it with a partner, nationally acclaimed artist David Aronson, who has perfected a quirky marriage between lowbrow and fine art elements. In Aronson’s art, Bradley found the perfect inspiration for his own unique brand of creative insanity. As Bradley told Aronson at one point in their long and fruitful association, “Each of your pictures contains a hundred different stories.”

In We’ll See Who Seduces Whom, Bradley explicates this statement by spinning hundreds of splintered tales based on Aronson’s pathologically delightful drawings. “We had one unspoken rule from the beginning,” says Bradley, “that I would have no conversation with the artist about the ‘meaning’ (if any) of his work.”

A complex and multi-layered dance between these two offbeat geniuses, We’ll See takes off in a high octane rampage, thunders across the defiled plains of Kansas, corners around the pope, takes multiple shots at our flabulous and star-struck culture, and brings you back home in time for a three-martini lunch, looking brain-raped and fuddled, woefully holding the book up and shaking it to see if anything more is to be had, secreted within its unholy pages.

“I invite you to unravel yourself,” says Bradley at one point, then proceeds to show the reader just how to accomplish that unraveling, with a flaying wit and a diabolical ability to pull half spun threads of story together and weave them into a sparse and breathtaking structure, balanced right on the precipice of reason. And then, in a change that occurs at the speed of light, lines come together into nice neat verses and hum along like down-scribed scat, smooth and charming and doing just what verses of poetry are supposed to do.

The interim sanity is never more than a quick flash, however, and soon Bradley begins another ascent into the heights of his own particularly cerebral madness, goaded on by Aronson’s precisely rendered and singularly disturbing images. Aronson takes the homey draftsmanship of an Edward Lear, and weds this deceptively innocuous style to clothonic images and odd juxtapositions of innocence and depravity, images from which Bradley wrings a universe entire of despair and death, demons and stinger-tailed angels to entice and horrify.

We’ll See Who Seduces Whom is a challenge from artist to writer and back again, and it’s impossible to read and not want to play along with Bradley and Aronson as they lob incendiary verbal and visual challenges at each other. In lesser hands a project like this could have devolved into self-absorbed dribble. But Aronson, who’s digital animation has been featured on MTV2 and Fuse and whose drawings and illustrations have appeared in Silkmilk, Ritual, Inside Artzine, Khooligan, and BigNews, has the sophistication to match well known poet and Bizarro author Bradley’s writing chops. In the end, it’s the reader who is wonderfully seduced into this amazing feast of words and images, coming away deliciously haunted and ready for more. A highly recommended read.

In Unlikely’s second offering, pleth, established poets j/j hastain and Marthe Reed collaborate on a work that is both visual and verbal. The title, a shortened form of the word plethora, is used by hastain to convey the writer’s multiple senses of self and as a reconfiguration of the he/she binary. Reed selected it as the title as a reference to the unfolding journey of gender awareness and identification captured within the book. The poems inside are smoky with intent, capturing the undulating dance of together/apart, brought to point by the fierce intellect of hastain and Reed.

hastain, well known for xyr cross-genre topics and post-gender advocacy, begins each call-and-response segment with collages that are both suggestive and introspective, drawing in the imagination with glimpses of sensual curves and ambiguous shadings and coloration – is that a hint of decay, or simply the delicate layering of tissue? Across each visual piece, hastain strews a spare handful of words, sometimes illuminating, sometimes an intriguing, intimate glimpse of internal dialog of pain and promise.

Marthe Reed, former creative writing program director at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and co-publisher of Black Radish Books, then gives her textual response in poetry so carefully honed, so precisely luminous, that each word resonates – with hastain’s images, with per words, and with Reed’s own scrupulously crafted poetry. At its heart, pleth is a passionate dialog about the crash point between cyber-entropic dissipation and the regenerative power of connection.

There are complex nuances in both hastain’s and Reed’s work, fragmented glimpses of post-apocalyptic wounds, of a desperate last grasp at the tattered shreds of a brave new world’s disavowed humanity, but both hastain and Reed offer, above all else, a sense of beauty, and of hope that shines through.

In a 2011 interview with Rob McLennan, Reed says modestly that it is not clear to her that poetry is any effective means of grappling with the larger social issues of the society around her. But it appears that in pleth, she has found her place. “We are …” Reed says, “tangent velocities abrading the knots.”

—

Deb Hoag is a writer with several published novels, including Queer and Loathing on the Yellow Brick Road and Crashin’ the Real, and the editor of Women Writing the Weird, an anthology of weird fiction by writers identifying as women. Her novels, as well as Women Writing the Weird and Women Writing the Weird II: Dreadful Daughters, are available at Dog Horn Publishing.

Big Lucks Books Wants Your Book

Where were you when that journal Big Lucks announced that they were going to start publishing books? If you were on the Internet, you probably saw this news received to tears of great joy and unprecedented numbers of Facebook shares. That was fun. 2014 will bring books by Mathias Svalina, Carrie Murphy, Sasha Fletcher, Mike Young, and Mike Krutel. Nice list!

What’s more, starting today and going until the end of November, Big Lucks Books is reading manuscripts. They’re using Submittable, and according to the call for submissions, here’s what they’re looking for:

We want to read your novels, stories, poems, memoirs, and essays. We want completed works only: no excerpts, proposals, or elevator pitches. We want fizz. We want earnest. We want heartbreaking. We want innovation. We want provocation. We want our paradigms shifted. We want you to fuck us up.

Interview: Sally Delehant & Emily Pettit

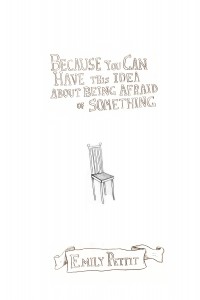

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Word is bond.

***

Sally Delehant: The title of the chapbook begins with the word “because” which positions the reader to assume a “why” question floats in the background of the text. I’m wondering what you think that question might be? Does it have to do with why we curl up to a specific person or part of our world? Or is the title perhaps an answer to the big question hanging above all of us — “Why write a poem?” Someone smarter than I am said in a poetry workshop once that on a basic level a poem works out or goes deeper into some kind of anxiety. Something is either resolved or agitated more. Do you agree? Do these poems work like that?

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

In response to your mention of poems being ways that one might work through or with anxiety, I think poems are often working in this way, being asked to work in this way. In regards to my poems, I’m hesitant to use the word “anxiety” because I feel like I use that word all the time in conversations I have with other people and myself and that its meaning is not containing what I want it to communicate. Or various things the word “anxiety” communicates, I worry negate or dim the things in poems that I’m looking for as a reader and looking to make happen as a writer. A friend recently shared with me the following Borges line, “The metaphysicians of Talon are not looking for truth, nor even an approximation of it; they are after a kind of amazement.” In poems I am looking for amazement rather than truth or an approximation of truth. For me amazement might be experienced through encountering two words, the juxtaposition of which make music to my ear or a striking image to my eye. I am looking to be amazed by a feeling that arises when I encounter the ideas, images and music that I encounter in poems. Why I write poems is to find these things that I am also looking for as reader. Anxiety is everywhere, but something I love about poems is that a poem is a place where I do not need to name anxiety, should I not want to. Naming things can give things power or an agency of sorts and the effects of naming things can be good or bad depending on too many factors for me to list here. Poems are a place where I feel I have control over what my brain and heart give agency to. And to a certain extent I have control over the effects this agency has. I have not found many places outside of writing where I get to experience this sort of control. In the poems in this chapbook there are ideas about anxiety and ideas about ideas about anxiety, but they are existing alongside often adamant ideas that anxiety can be controlled and sometimes productively ignored and denied. What it is taking me a long time to say is, I like how my imagination deals with anxiety more than the way other parts of me deal with it.

Sally Delehant

SD: In the first poem in Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something you write, “I freak out, freak out, freak out, / with a quiet mouth,” and as I trace the freak out through the poem (and chapbook) there seems to be tension between doing/being what one naturally does/is and what one could/should do and be if that makes sense. You can wear a nametag that says Emily or rabbit and in another sense be the “best refrigerator ever” as well as many other things. What I’m clumsily getting around to on this sleepy, Sunday afternoon is that I think part of our humanity tells us we should should should be a certain way and we fear we might be “the most ridiculous person (we) know” as you write later. The most beautiful and comforting thing we can hear is that we are good dogs. The speaker “wants to be a good animal.” She wants to let us know that we “are exactly where we are supposed to be.”

Are there things that make you think you aren’t where you are supposed to be? Without being intrusive I want to ask you one thing that scares you, and then I promise we can talk about the beautiful drawings in the book which I am curious about too. What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?

EP: I’m afraid me talking about fear outside of poems is like encountering a black hole. A hall of mirrors. My brain is exhausting in this way. I’m afraid that outside of my poems I fail to be funny about fear in the way that I want to be. I like that in poems I can feel funny about fear. I think anxiety and fear are absolutely linked. I have never encountered a definition of anxiety that does not use the word fear as a part of that definition. I like that when I’m dealing with fear in my poems, while writing poems, I do not feel anxious. Or if I am feeling something that could be defined as anxiety or fear, I’m not aware of it, or not naming it.

I think the thing that both my poems and my answer to your first question point to is a fear of both the presence and absence of control. It’s a conundrum. And I say conundrum, because I don’t think of a conundrum as hopeless. I like how in language with one word, conundrum, you can communicate a subject and a tone. For example, if you had asked me “What is a thing you are afraid of?” versus “What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?”, to me the first question feels much less scary than the second question. Naming me has given me a louder agency, more loudly bonding me to whatever answer I answer. One word. A word. A name. For me to explore fear or ideas of fear in a poem is a place that I am not as afraid of exploration. Exploration feels not just possible but exciting. In conversation and in prose (like writing this now) I have trouble with this exploration; I feel accountable to ideas leading to resolutions of sorts, resolutions that very possibly do not exist. Resolutions of logic that are not expected in poems. Or are not expected by me in relationship to what I think of as a poem. I’m afraid of many things. I’m very appreciative of a poem being a place where I can have some control over my fears and how they feel to my brain and my heart and my body. I’m very appreciative for getting to write poems and read the poems of others for the ways in which this engagement allows me to escape my fears.