Unlikely Books had two new releases in September, We’ll See Who Seduces Whom, with poetry by geniu-maniac wordsmith Tom Bradley, and truly twisted art by David Aronson; and Pleth, with textual poetry by Marthe Reed and artfully composed poetry cells by j/j hastain. Unlikely, which has been around as an online journal since 1998, began publishing books in 2005. After a relocation to Louisiana by Publisher Jonathan Penton in 2010, and a reevaluation of the current and upcoming publishing markets, neo-pulp online journal Unlikely has come back as Unlikely Stories: Episode IV, bigger and badder than ever, rebranding itself as a champion of transgressive literature.

Bizarro writer, political gadfly, prodigious poet Tom Bradley has done it again, once more turning the improbable into the compelling, showing us why he’s the guy mainstream writers wish they had the guts to be. This time, he goes it with a partner, nationally acclaimed artist David Aronson, who has perfected a quirky marriage between lowbrow and fine art elements. In Aronson’s art, Bradley found the perfect inspiration for his own unique brand of creative insanity. As Bradley told Aronson at one point in their long and fruitful association, “Each of your pictures contains a hundred different stories.”

In We’ll See Who Seduces Whom, Bradley explicates this statement by spinning hundreds of splintered tales based on Aronson’s pathologically delightful drawings. “We had one unspoken rule from the beginning,” says Bradley, “that I would have no conversation with the artist about the ‘meaning’ (if any) of his work.”

A complex and multi-layered dance between these two offbeat geniuses, We’ll See takes off in a high octane rampage, thunders across the defiled plains of Kansas, corners around the pope, takes multiple shots at our flabulous and star-struck culture, and brings you back home in time for a three-martini lunch, looking brain-raped and fuddled, woefully holding the book up and shaking it to see if anything more is to be had, secreted within its unholy pages.

“I invite you to unravel yourself,” says Bradley at one point, then proceeds to show the reader just how to accomplish that unraveling, with a flaying wit and a diabolical ability to pull half spun threads of story together and weave them into a sparse and breathtaking structure, balanced right on the precipice of reason. And then, in a change that occurs at the speed of light, lines come together into nice neat verses and hum along like down-scribed scat, smooth and charming and doing just what verses of poetry are supposed to do.

The interim sanity is never more than a quick flash, however, and soon Bradley begins another ascent into the heights of his own particularly cerebral madness, goaded on by Aronson’s precisely rendered and singularly disturbing images. Aronson takes the homey draftsmanship of an Edward Lear, and weds this deceptively innocuous style to clothonic images and odd juxtapositions of innocence and depravity, images from which Bradley wrings a universe entire of despair and death, demons and stinger-tailed angels to entice and horrify.

We’ll See Who Seduces Whom is a challenge from artist to writer and back again, and it’s impossible to read and not want to play along with Bradley and Aronson as they lob incendiary verbal and visual challenges at each other. In lesser hands a project like this could have devolved into self-absorbed dribble. But Aronson, who’s digital animation has been featured on MTV2 and Fuse and whose drawings and illustrations have appeared in Silkmilk, Ritual, Inside Artzine, Khooligan, and BigNews, has the sophistication to match well known poet and Bizarro author Bradley’s writing chops. In the end, it’s the reader who is wonderfully seduced into this amazing feast of words and images, coming away deliciously haunted and ready for more. A highly recommended read.

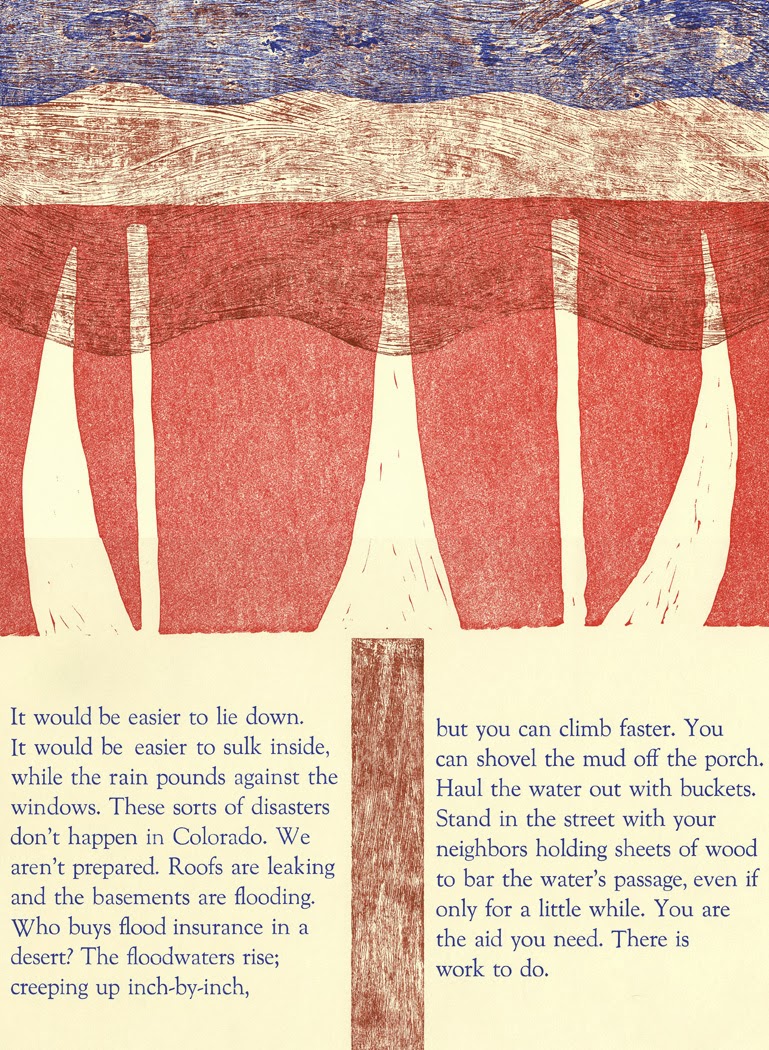

In Unlikely’s second offering, pleth, established poets j/j hastain and Marthe Reed collaborate on a work that is both visual and verbal. The title, a shortened form of the word plethora, is used by hastain to convey the writer’s multiple senses of self and as a reconfiguration of the he/she binary. Reed selected it as the title as a reference to the unfolding journey of gender awareness and identification captured within the book. The poems inside are smoky with intent, capturing the undulating dance of together/apart, brought to point by the fierce intellect of hastain and Reed.

hastain, well known for xyr cross-genre topics and post-gender advocacy, begins each call-and-response segment with collages that are both suggestive and introspective, drawing in the imagination with glimpses of sensual curves and ambiguous shadings and coloration – is that a hint of decay, or simply the delicate layering of tissue? Across each visual piece, hastain strews a spare handful of words, sometimes illuminating, sometimes an intriguing, intimate glimpse of internal dialog of pain and promise.

Marthe Reed, former creative writing program director at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and co-publisher of Black Radish Books, then gives her textual response in poetry so carefully honed, so precisely luminous, that each word resonates – with hastain’s images, with per words, and with Reed’s own scrupulously crafted poetry. At its heart, pleth is a passionate dialog about the crash point between cyber-entropic dissipation and the regenerative power of connection.

There are complex nuances in both hastain’s and Reed’s work, fragmented glimpses of post-apocalyptic wounds, of a desperate last grasp at the tattered shreds of a brave new world’s disavowed humanity, but both hastain and Reed offer, above all else, a sense of beauty, and of hope that shines through.

In a 2011 interview with Rob McLennan, Reed says modestly that it is not clear to her that poetry is any effective means of grappling with the larger social issues of the society around her. But it appears that in pleth, she has found her place. “We are …” Reed says, “tangent velocities abrading the knots.”

—

Deb Hoag is a writer with several published novels, including Queer and Loathing on the Yellow Brick Road and Crashin’ the Real, and the editor of Women Writing the Weird, an anthology of weird fiction by writers identifying as women. Her novels, as well as Women Writing the Weird and Women Writing the Weird II: Dreadful Daughters, are available at Dog Horn Publishing.

The Childhood of Jesus

The Childhood of Jesus