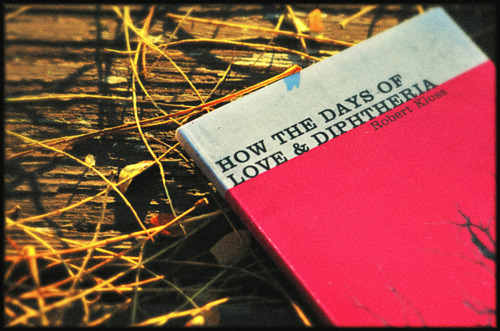

All of My Desire to be Involved: An Interview with Robert Kloss

Robert Kloss is the author of How the Days of Love & Diphtheria (Mud Luscious Press/Nephew) and The Alligators of Abraham (Mud Luscious Press, 2012). He is found online at rkbirdsofprey.blogspot.com.

Jackson Nieuwland: This is my first time being a ‘real’ interviewer. I’ve interviewed people before but they were pretty close friends of mine and I just posted the conversations on my blog. I don’t know you that well and hopefully this interview will be published somewhere cool. I enjoy interviewing, the finished product often feels like a significant achievement. I’m going to try and continue with my personal ‘style’ of interviewing here by asking you questions in bunches to be answered together and putting myself into the interview a bit (you are encouraged to ask me questions if the urge takes you). Have you been interviewed before? Have you interviewed people before? Do you have any interest in the artform of the interview? Do you read many interviews? What sorts of interviews do you prefer? Text? Audio? Video? What are your thoughts on each medium? Have you watched any of Nardwuar’s interviews? Do you have any favourite interviewers? Do you have any favourite interviewees? Are there any types of questions you particularly like or dislike?

Robert Kloss: I’ve interviewed a few people but I never really felt too comfortable with the process. It was fun and the writers I interviewed were very good to give their time and thoughts, but I don’t know that I had a knack for the form. I think a good interviewer is curious and is open to a certain process of discovery and I’m afraid I’m just not a very curious person. And, when it comes to people, I’m at the opposite of curious–the thoughts and particular cares or wants of a certain person just aren’t interesting to me anymore. So I don’t read or watch too many interviews. I don’t even read the letters or journals of famous writers anymore. Even if the conversation is profound (and they rarely are) I’m not sure I get much out of it. It wasn’t always like this. I used to watch Charlie Rose, for instance, because I was interested in World Figures. And I used to read interviews with filmmakers and composers and writers I admired. But I’m just not terribly curious anymore. That said, there are some people, some writers, who take the interview and turn it into a real art, a sort of extension of their work, and I do find that interesting/readable. Partly because I’m new to the idea of presenting myself to the wider world, and shaping that image in a certain way. But partly because while the mundane thoughts and opinions of some stranger aren’t terribly interesting, that stranger’s art probably is. I feel like any writing worth much is a reflection of the truest part of the writer anyhow so why shouldn’t the writer present themselves as what they are, a reflection of their art? READ MORE >

Glow-Rally: Kim Chinquee

They all wanted Cokes and the grandma said a beer please, and the boy’s father went and ordered, delivering while the pins clinked and banged and rattled.

Another train ride, and here I am with your goddamn strawberry lotion.

She tried to hide her breath, said she had a good day.

The lights were on and so I knocked and then the lights were off.

She was healthy and her laughter proved it, her laugh was like a cluck, like the chickens she used to feed, watch hatch, then butcher.

“What do we do with him when he’s dead?”

“She loved God,” the chaplain said. He was getting wobbly on the drum.

Later, lunch at Denny’s, we talked about what to do with the lorazep, trihexphen, risperidone, fluoxetine, the haldol in the lock box.

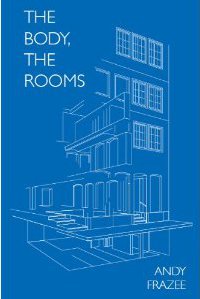

An Interview with Andy Frazee

A literary university press offer exposure for the students; the gap between writer and publisher blurs, has been blurring, as more and more one partakes in the work of the other. Why should an MFA only prepare a person for a profession in teaching? People enroll in ever-growing programs in order to write anyway (right?), not necessarily to teach. Writers, however, thrive with publishers. As mentioned later (in the interview), Ted Berrigan could staple together as many copies of his Sonnets as he likes, but everyone I know owns the copy published by Penguin. Why should this job be left up to a person with a business degree? Expanding an MFA degree to encompass, or at least introduce students to the business of books would not be difficult. Those who write have stakes in that buisness whether or not they are involved, so why not be involved?

A literary university press offer exposure for the students; the gap between writer and publisher blurs, has been blurring, as more and more one partakes in the work of the other. Why should an MFA only prepare a person for a profession in teaching? People enroll in ever-growing programs in order to write anyway (right?), not necessarily to teach. Writers, however, thrive with publishers. As mentioned later (in the interview), Ted Berrigan could staple together as many copies of his Sonnets as he likes, but everyone I know owns the copy published by Penguin. Why should this job be left up to a person with a business degree? Expanding an MFA degree to encompass, or at least introduce students to the business of books would not be difficult. Those who write have stakes in that buisness whether or not they are involved, so why not be involved?

The opportunity to be so involved in a press was exciting. Being part of the working relationship from the inception of making a manuscript into a book was rewarding and something I’m happy to have done. Below is an interview with the 2010 winner for poetry (published in 2011), Andy Frazee, whose book is available on Amazon or SPD.

Other books in 2011 include Alta Ifland’s Death-in-a-Box and Sandra Doller’s Man Years.

More information on Subito can be found on the website.

Stephen Daniel Lewis: One thing that surprised me about The Body, The Rooms was form. Not only that the form steps away from more standard types used in poetry, but the layout morphs section to section; sometimes even within a section the reader will see an evolution of the employed form. It was exciting to see how the usage of space encompasses the content in a way that seems inextricable.

I’m wonder what process led to this? Did the content come first, did it happen the other way around, or was it simultaneous? Also did you have specific reasons in mind for including elements that rarely surface in poetry (such as the explication that undercurrents the poems in the “Cartography” section, and the Dramatis Personae in the section titled “That the World Should Never Again Be Destroyed by Flood”)?

Andy Frazee: In general, content comes before form for me—not in terms of precedence, but in terms of chronology. For the most part, the content first comes in the form of journal entries and notes, which I at some point return to and cull for interesting phrases and ideas. A lot of the language in both “Cartography” and “In this Element of Capture,” for example, came from a series of sketches I’d written trying to re-write Eliot’s “Prufrock.” Both of those sequences have gone through many different formal manifestations, and I think this has a lot to do with my own attempts at trying to restrain an impulse to make the poem too organized, too logical. I often introduce some rudimentary form of chance operations to thwart that impulse—so at a certain point in the evolution of “Cartography” I listed out each individual sentence and dispersed them randomly in four-line sections over several pages. In the end, I go with what my gut tells me works, and that ultimately seemed to.

“Suspect nostalgia and equally suspect admiration for decay.”

“There is a collie here whose only countenance is the business-like countenance of a herder. He is unleashed, and he is unwavering in the anti-personal way he circles the gathered crowd. He has no time to be petted as he weaves through the people’s herd.” — For those of you who have been allergic to the arguably necessary but gratingly chalky rah-rah language of the Occupy movement, here is Anne Boyer in Lana Turner writing about Kansas City and making some good old fashioned song outta that fizz.

“There is a collie here whose only countenance is the business-like countenance of a herder. He is unleashed, and he is unwavering in the anti-personal way he circles the gathered crowd. He has no time to be petted as he weaves through the people’s herd.” — For those of you who have been allergic to the arguably necessary but gratingly chalky rah-rah language of the Occupy movement, here is Anne Boyer in Lana Turner writing about Kansas City and making some good old fashioned song outta that fizz.

The Savage Specifics of Such a Finale: A Conversation With Joshua Mohr

Joshua Mohr’s Damascus (Two Dollar Radio) is a tightly packed novel about the lost, losing, and broken people who frequent Damascus, a dive bar in San Francisco. The story is moving, bitterly charming, sometimes depressing, but always engaging. I talked to Joshua about his book, character driven writing, writing as a form of protest and much more.

I read Damascus as very character driven. It’s really the people and what you show us about their lives that create the narrative. Would you consider Damascus character driven?

Absolutely. Books don’t work if the people on the pages aren’t alive. It’s why writing a novel takes so long. You have to dig around in other psyches, other hearts and souls. The book isn’t going to be any good until your characters are the ones telling the story, and you’re just the poorly paid secretary scribbling it all down.

I teach in the MFA program at the University of San Francisco and when I talk characterization with my students, I emphasize the idea that actually the characters have to characterize themselves: the reader just sits back and watches the players stalk their sordid habitats. This kind of active characterization involves your reader in the story, too, making them put the pieces together for what each new scene means, how it contributes and complicates the action they’ve already observed. They become a kind of detective trying to compile an interpretation.

wallop

And the trouble people took to attach a modern-sounding label to these texts and to create a special genre-haven’t there been short texts since way back when? So people were, perhaps they still are, fidgeting with blaster, sudden fiction, flash fiction, prose poem and attempting to segregate these texts. The quality of the thing ought to be foregrounded. -Diane Williams

I believe a reader must work harder in interpreting flash, filling in those gaps with his or her own experiences. -Kim Chinquee

I love the immediacy of the medium–of reading a story that is not only compressed, but memorable in the images that are presented. -Meg Tuite

I had long admired the very short stories of Kafka, Borges, Hempel, others, before I gave the idea of length any real thought. -Pamela Painter.

I’ve been very interested to see what different writers have done with the very short form. It can go in so many directions, and whether one chooses a sort of mini-essay or mini-narrative or prose poem, meditation, etc., each will be quite different because the mind of each different writer comes through so clearly–the writer’s way of thinking, viewing the world, and then of course his or her way of handling language. In such a short form, each word has to be right. -Lydia Davis

I think my stories start fairly short, somewhere in the neighborhood of 200-300 words, and often stay there. -Chella Courington

I’ve always read the shortest stories I could get my hands on. It’s always appealed, the power to receive the full scope of a piece, to tour all the feelings the writer wants you to feel in one uninterrupted moment. It’s so easy to be brutal without consequence to characters in the shortest form. -Amelia Gray

I also think it’s the least egotistical form of writing. Not a lot of show-offs go into writing flash. None that I know anyway. -Mary Hamilton

The Other Poems interview with Paul Legault

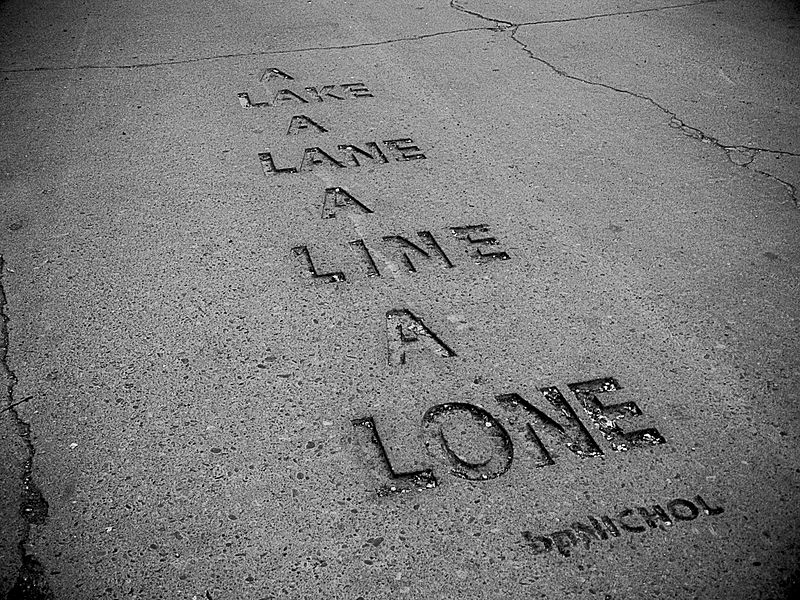

Sam Ross: Paul, your book begins with an epigraph from bpNichol:

From there the book erupts into a series of sonnet-dialogues with a host of personages, personifications, and “others”–from Whales, to Celibacy, to Mayakovsky as a Pony. Are these dialogues a means of approaching a dialogue with the self (as bpNichol suggests), mocking attempts at such a dialogue, or are the Others meant to be fragments of a unified self or whole (I’m thinking of a title of one of the Other Poems which begins: “We are made up of smaller version of ourselves stacked up on top of the smaller versions of ourselves….”). Maybe all three? Also, look at this!

(I like this.) READ MORE >

A Giant Triangle of Anxiety: An Interview with Mark Leidner

2011 has been a big year for Mark Leidner. Besides being one of the best things going on twitter, he’s also released two books: The Angel in the Dream of Our Hangover, a book of aphorisms from Sator Press; and Beauty Was The Case That They Gave Me, a book of poems from Factory Hollow Press. Each are singular in that they somehow manage to be both hilarious and uncannily gorgeous in their method of exploration, seeming to hyper-compress big ideas into forms that in lesser hands would seem absurd. Over the past couple weeks, Mark and I exchanged some emails about his books, sincerity, humor, religion, logic, and terror, among other things.

* * *

Butler: The Angel in the Dream of Our Hangover reads mostly like a book of aphorisms, which is an interesting format to take up. I think a lot of it reads as very sincere, even when it is using strange spins on the traditional aphorism, such as fatherfucker, or what some would consider “ridiculous imagery” such as punching water. I wonder if you knew you were writing a book of aphorisms, if you see it that way, and how this began to come together and form a book?

Leidner: I was trying to write aphorisms on purpose. The book didn’t begin that way though. Initial drafts contained more ironic or jokier stuff – the kind of thing that in the heat of the moment on Twitter can be exciting – which is how Ken Baumann the publisher first approached me – proposing a book that would begin as a carefully selected arrangement of tweets – but as the book grew, we felt the center start to cohere around the aphorism. A line like “what if hot dogs were the cut off horns of meat unicorns” can be interesting on Twitter because in Twitter it will burst into your feed like a surprise, it’ll be free, and there won’t by any high-minded literary expectation waiting for it in you. But copied & pasted into the literary form of the book and it becomes much more boring (at least to me) especially if it’s a book I’ve paid for, because while briefly interesting, its central juxtaposition doesn’t target anything I more than superficially care about. Great tweets give you a huge reward up front at the expense of lasting power. But a good aphorism rewards you more the more you think about it, partly because it is attached to some enduring concern. But that’s their downfall. Generalizing about grand themes is didactic – so the challenge of writing them in a way that honored complexity was very exciting, and pushed me into ridiculous imagery that felt both personal and universal. READ MORE >

A Kind of Weird Beauty: Michael Bible’s Simple Machines

Michael Bible is the author of Cowboy Maloney’s Electric City, as well as the chapbooks Gorilla Math and My Second Best Bear Rug. He was winner of the ESPN: the Magazine/Stymie fiction prize. He lives in Oxford, Mississippi where he edits Kitty Snacks.

Michael Bible is the author of Cowboy Maloney’s Electric City, as well as the chapbooks Gorilla Math and My Second Best Bear Rug. He was winner of the ESPN: the Magazine/Stymie fiction prize. He lives in Oxford, Mississippi where he edits Kitty Snacks.

Michael Kimball: I’m curious: How did you get the title? That feels like it must have been a key to writing the piece.

Michael Bible: As far as Simple Machines goes, the title actually came to me after I wrote it, but you’re right, it sort of crystallized it for me. I started the manuscript after I read The Policeman’s Beard is Half Constructed and I was playing around with random sentence generators and ESL textbooks. I love sentences that are used as examples for school. (Has someone written a book of word problems? Also, that would be a good title. Probably somebody’s written it.) There is an oddness to those example sentences that I love, “bad” writing as “good” writing. They have a kind of weird beauty and they seemly have no context but somehow make stories anyway. Simple Machines is also something I learned about in school so it made sense that that would be a good title. READ MORE >

An Excerpt from Jarett Kobek’s ATTA

New from Semiotext(e) is Jarett Kobek’s ATTA, “a fictionalized psychedelic biography of Mohamed Atta that circles around a simple question: what if 9/11 was as much a matter of architectural criticism as religious terrorism?”

He prepares himself, watches television, hopes the box displays violence. But television is coy, intimates killings as abstractions. Beatings, certainly, beatings and brutality. But minimal death. Always the moment after. Police crash into a room, find a body, hunt the killer. But the actual kill? Off-screen. Or with guns. And what can he learn from guns?

Atta opens a video rental account, chooses movies that help with knowledge of death. He rejects Hollywood fantasies, imperialist propaganda efforts, prefers outlandish tales of monstrous abuse. The Horror section. Blood explodes in these films, bright red replica splashes on skin. READ MORE >