POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#14)

TJ Lyons is in California doing things that dudes usually do. His first book, Things, will be out soon from somewhere awesome. Things are always what they seem. tjisadude.tumblr.com

I think I sleep in a peel that fits me better than a collar

by

T.J. Lyons

This poem came from my experience living as a banana in a Safeway for nine days before the produce people noticed me, and then they marked me down. An old woman with a pegleg bought me. This will appear soon in the ebook, The Wind Cannot Remove the Stench in My Bones, with art by Andrew Jurado.

in a Safeway for nine days before the produce people noticed me, and then they marked me down. An old woman with a pegleg bought me. This will appear soon in the ebook, The Wind Cannot Remove the Stench in My Bones, with art by Andrew Jurado.

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

February 17th, 2014 / 11:26 pm

Interview with Marek Waldorf

Braver than most, Marek Waldorf has dared to spin literature out of the terrifying realm of political speechwriting. His debut novel, The Short Fall (Turtle Point Press), follows a speechwriter for a presidential campaign who has been left disabled after a botched attempt on the nominee’s life. In dense, lyrical prose, the narrator explores the campaign from its nascent form to the disastrous present, winding in and out of events as they lead his body to cross paths with the assassin’s bullet. If you think you’re up for a Bernhard-style treatment of American political rhetoric and its relationship to authenticity, idealism, and image making, then look no further. Marek was kind enough to answer some questions for HTMLGIANT via email.

***

Hal Hlavinka: In your professional life, you write grants for nonprofits like Girls Write Now. I’m interested in how your day-to-day contact with bureaucratese informed the lexical and logical frameworks of The Short Fall. More specifically, as the speechwriter’s paranoia unfolds, we start to read all sorts of fragmentary beliefs about the relationship between language and charisma, politics and fundraising, and I wonder to what degree these connections are carved from your day job.

Marek Waldorf: Grantwriting’s unusual in that you’re writing for a literally captive audience. Foundation officers are paid to read what you’re paid to write, allowing more freedom to be boring than, say, speechwriting or marketing. The latter I have very little understanding of. To be honest, I hadn’t moved into fundraising when writing The Short Fall—I was still a temp. But does the job involve more linguistic depletion than other writing professions? I don’t think we do too much damage: at one funder’s meeting I recently attended, grant applicants were encouraged to “step free of the jargon zone.” I’ll travel in & out of the zone fairly regularly, but I’m also—maybe more—interested in the infantilizing uses of language.

And TSF is less an immersion in bureaucratese than a recounting—a very long thought-balloon—of how people function within such immersion: the self-justifications, pretty stories, petty (&-not-so) delusions. There’s a recurring joke in TSF—particularly, section two—where the speechwriter spends pages explaining his craft & straining mightily on the pot of composition all in the service of (for instance) “A new day is rising in America.” Or let’s just say—one man’s unique susceptibility to language & its gaming.

HH: At your reading in Chicago, you mentioned that part of your strategy for writing The Short Fall, at least in the beginning, was to explore the narrator’s voice inside a dense, elliptical framework in the style of Thomas Bernhard. Can you talk a little bit about the challenges and benefits of using Bernhard’s notoriously demanding narrative aesthetic as a guide?

MW: Bernhard’s The Lime Works was a driving influence for sure—his books sort of cocoon the period of TSF’s writing. And, yes, I’ve often wondered about your well-taken second point. I worried Bernhard’s aesthetic wasn’t something you dabble in, that it demanded a lifelong engagement, but—fortunately for the book—I was chafing as well, right from the start. While there’s a show-off quality, an exuberance, to Bernhard’s style, it’s not one he conjures up at the level of “turning a phrase.” Whereas I can’t help myself. Two books I read during that period—Nicholson Baker’s U & I and Alexander Theroux’s An Adultery—seemed like masterful and disrespectful negotiations of that aesthetic (as is, I believe, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be). To see distinctive work occupying the same ground that wasn’t pastiche—resemblances surfacing almost as matters of temperament—was reassuring. Of course TSF is also pulling hard in the direction of the American maximalist novel of disintegration. The politics, the stamp of its ambition, the presiding question of authenticity—all contrive to keep it on native soil.

HH: You began writing the novel in the nineties, only to finish it over a decade and two presidencies later. To what extent did your writing change—first with the Lewinsky scandal, followed by the disastrous Bush tenures, and finally the bittersweet state of the Obama administration—as the office and image of the POTUS has changed?

MW: I had TSF pretty much finished by 1995, so it is interesting to see what’s changed since I wrote the book, and what’s stayed the same, given the 20-year gap. The Society of Victims, for example, started life as a pun-laden left jab—watching it metastatize within the real world vs. the book has been interesting. And the emphasis on a politics of infantilization worked out well it seems … witness our progression to ubiquitous bathroom-acronyms like POTUS & SCOTUS! I’ll say this about political and science fiction, having attempted both—prescience ranks among their highest virtues. But mostly I feel the oddness of returning to something written by a much younger me. Its youthfulness detains me, and when I write about it now, I feel a bit like an impostor.

My hope at the time was TSF would welcome a certain type of reader, which wouldn’t necessarily track to how s/he voted. I’m not sure I succeeded entirely, but I believe the pressure of that instinct—to abstract out of partisan politics—was helpful. In retrospect, the Clintonian triangulating which led many of my peers to cynical despair &/or a vote for Nader feels like TSF’s operational baseline. The politics of encroachment-from-the-middle isn’t what’s happening now—Bush certainly changed that—but it’s due for a comeback, I imagine, and it doesn’t matter for the book, because the narrator has burrowed so deep into the campaign he doesn’t see Vance as up against anybody—only chance—and the idea of an alternative arises in terms of rhetorical tactics … as deployment, a trick. My aim in all this wasn’t ambiguity so much as an absence, like everything else below the neck the speechwriter can’t move or feel. Like SCOTUS, he’s all head.

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#13)

Alexandra Naughton does a lot of things and her name is very search engine friendly. Her first book, I Will Always Be Your Whore, was published by Punk Hostage Press in January, 2014.

Love Song #1

[Ava Adore]

by

Alexandra Naughton

![]()

Someone: “HTML Giant is so sexist…”

Nigel Tufnel: “What’s wrong with bein sexy?”

![]()

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

January 28th, 2014 / 9:41 pm

Sportin’ Jack by Paul Strohm 28.5 Points

- Shattered clock of memoir flashes. Thinking Abigail Thomas, John Edgar Wideman (in Harper’s or some mag like Harper’s a while back), Baudelaire, Between Parentheses, fuck I don’t know. Calling for flash nonfiction collection authors.

- The cover has a guy holding tiny baby chicks, as you can surmise. The chicks look like clay or bewildered paper balls.

- The real angling or net fishing is memory.

- Can you recall 5 stories from when you were age 10, maybe 5 interactions with dogs? Neither can I. Where did they collapse?

- Every flash, all 100, is 100 words. That’s called a drabble in fiction. Not exactly Oulipo but it has an effect, like a painting of a vulture in a mirror. Aesthetic restraints lead to increased creativity (and technique), not decreased. Perec taught us the wanderer can own the wall.

- Language leads on like a forehead, and seems to fulfill at time, the writer.

- I sense a cobweb fatigue with pretentiousness. You can feel a jacket being shucked and thrown crumpled to the floor.

- Writer asks, wonders, “Who was this Jack?”

- Shame, for example. A drowsing duck inside the chest cavity.

- My favorite line: I was wooing a Kansas City woman. Very Chinquee, in its direct way.

- I also enjoyed, “She died from alcohol, but nobody ever saw her take a drink.” READ MORE >

January 28th, 2014 / 3:46 pm

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#11)

Penny Goring lives in London. She makes things, and collaborates with Hella Trol Buzy to make other things.

please make me love you

by Penny Goring

![]()

i wrote it on new years day. i used that can be my next tweet, getting computer generated mashups of my recent tweets, then reshuffling, discarding, and adding words. when a line is done i tweet it. because: it’s faster than opening another tab, it makes writing less lonely, it’s interesting to see what lines get favd/retweeted/ignored, and seeing my lines in the twit stream helps me get distance. when i felt like i’d made enough, i copy/pasted each tweet into openoffice and did edits. i like repetition, variations. i feel self-indulgent when i write lists – it is a falling. on new years day i wanted to fall in love.

when a line is done i tweet it. because: it’s faster than opening another tab, it makes writing less lonely, it’s interesting to see what lines get favd/retweeted/ignored, and seeing my lines in the twit stream helps me get distance. when i felt like i’d made enough, i copy/pasted each tweet into openoffice and did edits. i like repetition, variations. i feel self-indulgent when i write lists – it is a falling. on new years day i wanted to fall in love.

![]()

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

January 15th, 2014 / 8:39 pm

Interview With Luis Panini

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Janice Lee: In your other life, you’re an architect and furniture designer. I’m interested in how this work and mode of thinking influences your stories. For example, the preciseness of your language, the constructedness of your stories as rigid and stable structures, your attention to spatial details and spatial relationships, and the existence of people and objects in physical environments rather than in relation to each other.

Luis Panini: My academic background has not only influenced the way in which I think about stories before I actually write them but also it has made me think about overall structures when I am constructing (not writing) a book, whether is a collection of short fiction, a novel, a book of poems or some piece of writing that does not necessarily falls into these ankylosing categories. Spatial awareness is very important for me since it is ultimately where the “game is played” and this is why I frequently try to inject some sort of symbolic meaning to both, the spaces my characters inhabit and the objects they come in contact with. In a way, what I am trying to accomplish is to integrate these “architectural objects” into the narrative in such a way that these become as important as the characters or the story itself. It is about translating the mere functionality of a space or an object into an emotional component in the writing process or how this space or object is acknowledged and assimilated by the reader. Duchamp’s “Fountain” comes to mind. He managed to transform a simple urinal into an object charged with many layers of meaning by placing it within the confines of a “sacred space.” Outside the museum, Duchamp’s piece is nothing but a urinal. Inside the museum is everything but a urinal because the reading conditions of this object have been transgressed. This is the sort of relationships I like to establish between my characters and the space they move about.

JL: You’ve described your stories as vignettes or fragments, and I think they operate in this way, but too, at the same time, they seem like such self-contained and intentionally built structures that do have set boundaries. Can you talk a bit more about the general shape of your individual stories?

LP: I did refer to those texts (the ones collected in my second book) as vignettes or fragments because that is truly what these are. They are absolutely self-contained pieces of writing. I like to think that the most interesting building block in writing is not the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, etc. but the fragment, because a fragment does not require a beginning or an end, it does not need to tell a whole story to work, it does not have to acknowledge the fragment that precedes it or follows it and I find this to be truly liberating, a sense that I do not get when I take a different approach. About a year or two ago I finished writing a book that deals with memory and it is comprised of more than one hundred fragments. There are two versions of that book. In one version the fragments follow a chronological order of events and in the other version the fragments appear in the order in which they were written, the order in which I remembered a loved one who died recently. I chose to write about that story through fragments because in a way I wanted to emulate the mechanisms of memory and a fragmentary approach made perfect sense since I could experiment with the elasticity of the overall structure (or lack of one) by allowing a virtually infinite number of permutations. This also allowed me to set very strict boundaries on a fragment bases that I had to respect as I was writing each line. Every time I deviated in any way from those boundaries, the fragment did not work. It felt like an ill-conceived part of a whole. Through this method of writing I learned about the shape of not just individual stories but also how these can be connected in a book and how they interact among themselves by borrowing, cannibalizing from each other, etc. A book composed of fragments can be dozens of different books, only limited by the sequence you end up choosing.

JL: I know you are a Béla Tarr fan too, and I find that there are some resonances in your work with Tarr’s fans. For example, the focus in your stories is often on a person’s existence in a space or situation, and the story settles in on the details of the environment, constructing a scene that becomes a sort of story, rather than a story that is based on action and resolution. This reminds me of the indifference of the camera in Tarr’s films too, where often the setting is there before a character enters, and remains there after the character is gone. What are your thoughts on this observation?

LP: Sometimes I think that filmmakers are the ones who truly influence my creative process and writing methods, much more than literature in general or specific writers and books, and this has nothing to do with the fact that I live in Los Angeles, a city in which if you mention that you are a writer most people immediately ask you what screenplays have you written. Béla Tarr is one of these auteurs (I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed seeing that old man peeling potatoes in “The Turin Horse”), but also I am fascinated with the way other directors choose to tell stories, like Michael Haneke, Yorgos Lanthimos, and my personal favorite Ruben Östlund. I am not trying to say that my literary work has a cinematic quality or that it could easily be translated onto the screen, but this element becomes quite obvious since I tend to favor heterodiegetic narrators in most of my texts. I like to take it to the extreme, turning them into machine-like narrators which can be perceived as actual cameras panning through multiple rooms in a residence to create some sort of long shot composed by zoom-ins, abrupt cuts, blurs, etc. My vignette titled “The Event” is an example of this. After the character has “disappeared” in a very tragic way the camera goes back into the apartment where it all began and stays in recording mode to capture the solitude of the space, which to me is far more important than the demise of the actual character. In another vignette the narrator also acts as a camera that moves inside of a mansion to capture many of the possessions of a lonely man dying of complications related to an immunological disease. I was not interested in that man’s story specifically, but in how I could construct one by describing the pieces of furniture and ornaments he owns, the art hanging on his walls, and the materials and finishes of his home. I guess by doing this I am trying to illustrate some sort of terror that sometimes keeps me awake at night, the fact that after one dies everything else remains in its place, unaltered, because we are that insignificant. And it is this sense of pervasive malaise what informs most of my writing.

JL: I’m affected deeply by level of compassion and human dignity present in Tarr’s fans. On this subject, Andras Balint Kovacs writes:

“The man, whose philosophy despises ‘humanist’ feelings like compassion and pity, suddenly and certainly unwillingly, manifests the deepest compassion for a helpless living being, a beaten horse. This event, says Krasznahorkai, is ‘the flashing recognition of a tragic error: after such a long and painful combat, this time it was Nietzsche’s persona who said no to Nietzsche’s thoughts that are particularly infernal in their consequences.’ This is the example which leads to a conclusion about the universality of this feeling: ‘if not today, then tomorrow… or ten, or thirty years from now. At the latest, in Turin.’ … an attitude or an approach to human conditions, which Tarr fundamentally shares with Krasznahorkai… Both authors have a fundamentally compassionate attitude toward human helplessness and suffering in whatever situation it may manifest itself, and of whatever antecedent it may be the result.”

In Tarr films, compassion can exist without moral judgment, or, in other words, “In the Tarr films human dignity is not based on morality. It is based on the fact that in spite of their absolutely hopeless and desperate situations the characters remain what they are, however low what they are brings them.”

This simultaneous closeness and distancing, this empathy is ever-present in your stories for me too. For example, in “Mathematical Certainty,” there is a deep care in the description of the hat, but also in the generous curiosity afforded to the man with the brain tumor. I also recently heard Lydia Davis talk about description, and said something like, “In order to describe something, you have to love it. Even if it’s ugly, like an old shoe, you have to love it in a way to really describe it.” The preciseness of your language and the kind of curiosity afforded by such a detail as the length between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, seems like a generous gesture in a way. What are your thoughts?

LP: I believe empathy and compassion is what drove me to write the vignettes included in my second book, as strange as that may sound given the dark nature of the overall subject matter of those texts, which is ill will. In fact, I can pinpoint the exact moment that acted as the catalyst. Back in 2006 there was a terrible brush fire, which consumed an enormous area near Los Angeles. For some reason that I yet have to comprehend a news show chose to broadcast a recording with no “viewer discretion advised” warning beforehand. I saw the body of a fallen hare partly carbonized. It was still moving, shaking the rear legs, convulsing, agonizing. And it affected me so much because animal suffering is something I simply cannot deal with. So this visceral reaction prompted me to explore this feeling in different ways, in fact so many that soon became a book about ill will. Ill will towards animals, patients with terminal diseases, sexual partners, art, even towards the reader. The main character in “Mathematical Certainty” is a man who soon will die of a brain tumor he has chosen not to have surgically removed. Instead, he decides to buy a white hat to conceal, maybe in an unconscious way, this organic tissue developing inside of him. Growing up in a predominantly catholic environment I heard many people say that the real reason why a man or a woman got cancer was the result of divine punishment, as if sinful behavior (whatever that means) could trigger it. So, in a way, that particular vignette is about religious ill will, the supposed shame caused by the disease, thus the comparison between the hat and a crown of thorns. Again, I was not too interested in the life of this character, but in presenting a juxtaposition of elements, such as a man fully dressed in white with something truly dark growing inside of his skull, and more so in determining the distance between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, because those particularities or insignificances are what fuel my desire to write. I don’t want to write about the victims of a serial killer or the reasoning behind his actions, instead I want to write about the way in which this terrible person peels potatoes.

January 15th, 2014 / 10:00 am

FUCK YER BRAND, IMMA DO ME (/help me figure out my brand?)

[u shd probably read the NOTE(S) as they come up for cohesion, but do as u wish, obvi]

so there s a lot of things that have been going on here, on our dearly beloved htmlg. there seems to be an even bigger emphasis than ever before on attn. and i won t lie, it is nice to feel that w/e it is i might have written here might have been read or provoked a thought to someone—ANYONE—outside of me. but the reason i am writing this, right now is to set up a personal statement of sorts for how i want to use this site, as someone who regularly (?) tries to put stuff up…

MISSION STATEMENT(S)

I will refuse to care about being “cool.” I reject the notion of a grotesquely narcissistic coolness in an alt lit universe, where we are all nerds, when viewed through the larger lens of people who are not only unaware of this lit stuff, but also actively ignore its existence.

Perhaps I am just the biggest loser in the universe, but I like to care. If I did not, maybe I would not want to write. The reason I started writing was to figure out things I was genuinely curious about, not always in a healthy fashion. It was not to one-up anyone, not to be smarter in a gimmicky sort of way that will fade and might feel cheap in a couple of years.

HTMLG was one of the places online I constantly returned to when I was in a cubicle day after day doing shit I hated, trying to find a way out. To me, it used to be a liberating space, a meaningful forum that introduced me to writing I care for, and still value. Now, it is confusing. I have the hardest time figuring out the intentions behind what is being written. Sometimes I wonder if pressing “publish” was the entire goal of some contributor; I do not think it should be. [1]

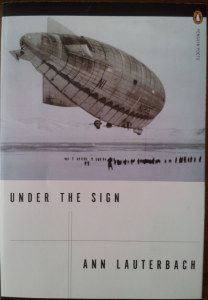

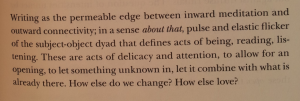

An amazing book of poetry was loaned to me, to remind me of my incentives and goals. Ann Lauterbach is brilliant, even though she cares. Or maybe because of it. I do not write poems, but her intentions—as presented in the middle section of “Under The Sign” are ones I would like to have as ideals.

So perhaps caring is not so bad. I will not actively try to not care about writing; writing by those who don’t care does not interest me.

But to care, one needs to put something at risk. One must “open,” perhaps even lose a part of their “security”—usually stemming from exercising a controlled performance of confidence—by showing insecurity. Being clevererererer just shouldn’t cut it if one wants to be true to oneself. [2]

I like the way Lauterbach understands writing. I wish we all agreed on that a little more, but I won’t force it upon you, because that would go against my principles.

NOTE(S)

[1] It is entirely possible that the reason I feel this way about putting words together in a creative way is because I did not study it. Maybe the excessive studying of something leads some of my fellow HTMLG contributors to an insipid cynicism that is often reduced to “being smarter.” Maybe it has to do with the frustrations of a young writer—or new, actually— as an immaterial existence in a material universe: the rewards of writing are rarely fiscal.

The fixation on rapid success that is intrinsic in late-capitalism has infected our immaterial universe, stigmatizing creative intentions. And I am aware money is—and probably will be—an issue for a lot of us/ you/ whatever you want me to say. But to let it dictate creative intentions would be embracing defeat.

Meet Charles Ozburn: His Work, Thoughts on Childe Harold, Etc

***

After I read at Mellow Pages in the Fall I was greeted by a man with a deep voice. I was in a bit of a fog-tunnel, as I usually am after readings, and it took me a while to figure out that this man (Charlie – Charles Ozburn) was speaking about Tiresias: variously male and female, etc. One of the great things, of course, about reading in different places is that you meet new and sometimes great people. Charlie is an example of the latter. And, soon, I found out that Charlie has a real and sustained “thing” for the club-footed Lord Byron’s work. And, in particular, Childe Harold. So, into the late hours that night I Brooklyn hung out with Charlie and other Mellow Pages folk. And then kept in touch with Charlie.

***

And, so, anyways, to follow is Charlie’s take on why Byron and Childe Harold are still highly relevant as well as a couple of samples of Charlie’s novel, A Well-Spun Spoon (of a Lark, a Lily & a Loon), where he attempts to “reflect the contradicting faces of Childe Harold against one another to, in Venus Effect, split the Byronic Hero into two (a he and, of course, a she)”

***

RK: I’ve seen the words “Childe Harold” in print a few times, I guess, but I don’t believe I’d ever heard them in conversation before I met you. And I know Byron’s work, especially “Childe Harold,” is important to you. But can you tell us please why it’s worth reading?? (what could a reader get out of it that he/she can’t get anywhere else)

CO: There exist some very basic assumptions of the human condition called human emotion, which–as expressed within an artistic medium, a plot line or even day-to-day interaction–may seem simplistic today. However, without Childe, such assumptions do not exist. For from Byron’s ink was born the founding strokes of the Modern Man, but nonetheless it is ink so far ingrained within our beings that it is often taken for granted today if noticed at all. Childe’s mark, like the faded mirror you see, is as ubiquitous as is felt; as important as is faded as is masked as is shrouded dark; more heard in the echoes of our subconscious than is shouted aloud; certainly more misunderstood as a literary key word taught to the too young an age to be realized any substantive credit due. For everyone knows of Lord Byron and, of course, every Dick or Jane, who ever paid a bit of attention in high school English has heard, if only in passing, the term ‘Byronic hero’ – but, given you are not the first person–much less poet–who has with earnestness admitted to an honest ignorance of Byron’s legacy, I suppose it is safe to say today that the roots, flowers, fruits and weeds born of Byron and his work have grown so tall, so far, so wide, so plump, so beautifully wretched, so wretchedly right, so obviously plain that the shadowing stature of their booming bloom have all but sheathed the very soil and seed from which beneath same sprouted.

Childe Harold is the lightly veiled pen-to-page fictive form of young Lord Byron written contemporaneously in reflection along his own path from disillusioned playboy gamboling in retreat of war about the exotic pleasures fields of faraway fanciful worlds to finding therein the world out there lay so much more than perceiving one’s own superiority and self-serving one’s self righteousness of pity in vain; because so many of us today with our world and war weary eyes and smug cachets find ourselves in his same embarkation shoes, entrapped in a claustrophobic cynicism our own and gamboling about lost in this newly found unfamiliar land where all are free to know all; because not only did Lord Byron embody all things Rock Star, but because he so clearly invented the role; because he was Andy Warhol 100 years before Campbell canned its first soup; because he was Lou Reed and Patti, Janice and Jerry, and Richard. Levon and Rick 200 years before Chelsea changed the game or Monterrey poised itself to pop! because he was the most famous READ MORE >

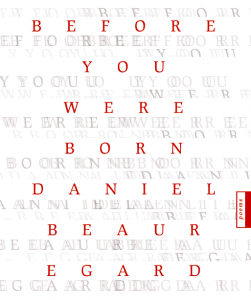

Daniel Beauregard Release Day Interview Party!

Today, my new press, 421 Atlanta, releases Daniel Beauregard’s debut chapbook, Before You Were Born. First things first: you can order it here, or here if you want to get a great deal on both it and Publishing Genius’s newest chapbook release, The Kids I Teach by Andrew Weatherhead and Mallory Whitten. Speaking of Publishing Genius, I thought I’d take a page from PGP man (& BYWB designer) Adam Robinson’s playbook and post a quick but savory Q&A with my author so that HTMLGiant readers can get to know him a little better! It was really interesting to think about Daniel’s poetry as an interviewer instead of as a publisher, and I was very excited to see his thoughtful and candid answers to my questions. And here they are!

Today, my new press, 421 Atlanta, releases Daniel Beauregard’s debut chapbook, Before You Were Born. First things first: you can order it here, or here if you want to get a great deal on both it and Publishing Genius’s newest chapbook release, The Kids I Teach by Andrew Weatherhead and Mallory Whitten. Speaking of Publishing Genius, I thought I’d take a page from PGP man (& BYWB designer) Adam Robinson’s playbook and post a quick but savory Q&A with my author so that HTMLGiant readers can get to know him a little better! It was really interesting to think about Daniel’s poetry as an interviewer instead of as a publisher, and I was very excited to see his thoughtful and candid answers to my questions. And here they are!

How did dreams, objects, and found texts interplay with your process in writing the poems in your new chapbook?

Dreams played a very large role in writing the poems found in “Before You Were Born.” In a way I feel many of the poems were dictated to me through my subconscious—at times I woke in the middle of the night after a dream and the dream became the poem. Other times, things came more sporadically, a line at a time. When I added the lines together they made sense. Or they didn’t. I have a dry erase board next to my bed and if something comes in those hours between waking and dreaming that is important to me, I straggle out of bed and write it down usually without turning on the light. Then I go back to bed or, if the lines keep coming, I’ll turn the light on. Objects played a large role in writing the poems as well. I was obsessed with the way things can be continuously broken down then built into something new. Like an atom bomb or a pulsar. I didn’t rely on found text in these poems as much as I have in my more recent work. However, there are a lot of bits and pieces I’ve picked up along the way that have wedged their way into the poems—conversations, arguments, emails.

And how about The Simpsons?

The Simpsons is always somewhere inside me D’oh. There aren’t many references to the show in “Before You Were Born” but I did steal a line from Superintendent Chalmers. It’s from a scene when Chalmers and Principal Skinner are walking in the parking lot and Chalmers shows Skinner his new car. Skinner says: “It gets me to from A to B—and on weekends, point C.” I do have several other poems that reference the show though.

There’s something about the poems in Before You Were Born that seems, not personal exactly, but private. How do you think about audience and the reader?

There is something that’s a little private in those poems because, in a way, it’s asking the reader to take a step into my mind—to see the things that I obsess over; the things I rant about. Tiny particles. Dust being bits of skin. Swamp lights and the souls of dead children. I don’t like to think about the audience and the reader too much. I like the idea of the reader looking into a glass house. You can throw whatever you want at it but the house will stand or melt into something else, all the while a part of me will remain. These poems are an exercise in understanding myself—they are very much selfish.

What are you working on now?

Lately I’ve been interested in how caves can be used as a larger metaphor for language. I haven’t thought too much about it yet but I’ve begun studying caves via various texts and hopefully over the next few months I can visit some caves myself. I’m interested in how life can thrive in the depths of these caves without any sunlight—bacteria, viruses, extremophiles—not exactly sure where it will go but I’ll continue playing with the idea of desiccation, dissolution and creation. I’ve also got another project titled “HELLO MY MEAT” that I finished recently. It’s a series of loose sonnets created from words and phrases found in various anatomy texts, letters from sea, captain’s logs, butcher manuals and sea diaries from the early 1900s.