Jay-Z may not be the best rapper, but…

…he’s apparently a big fan of eating under a picture of Proust. And, he’s a Satan-worshiping member of the Illuminati. So, big up to Brooklyn.

How does Luca Dipierro do it? Check out the trailer he made for WORDS, by Andy Devine.

Mr. Hathaway

Clocked-in a reading recently by Mitchell L. H. Douglas. I was immediately glow, since he writes Persona Texts (I call them), specifically Donny Hathaway, his family and friends, his life.

Clocked-in a reading recently by Mitchell L. H. Douglas. I was immediately glow, since he writes Persona Texts (I call them), specifically Donny Hathaway, his family and friends, his life.

Douglas is on a mission. He feels we have forgotten Donny Hathaway.

Many of the poems are the same poem, rewritten, reformed, re-done. Like jazz or mornings. Spun off into new territories, into improvs and pops and jams.

I was impressed. I told a student: “I want you to read his book and interview that poet.” A perk of teaching college is that you can assign such notions and the student pretty much will follow through. Grades are involved and so on. The student is named Aaron. This interview appears in the 2010 Broken Plate. And now online below:

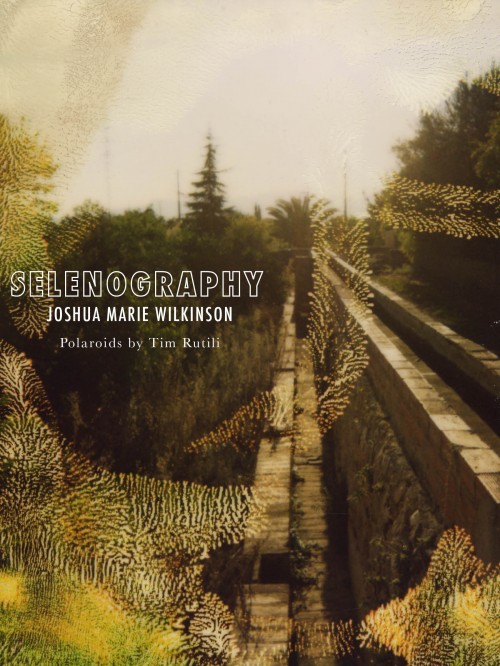

Live Giants #3, with Joshua Marie Wilkinson

You missed the reading but you can still pick up Joshua’s new book:

Up until about 9 PM on Wednesday night, Selenography will be available for a 25% discount, $15, from Sidebrow Books. I got my copy yesterday, and it is a beautiful thing to hold. Snatch it up.

You can also get Joshua’s book in package deal with the other brand new Sidebrow release by Sandy Florian, along with the Sidebrow anthology, which is incredible, all for $30. Again, this is a deal that will go on through the show and 24 hours thereafter. Enjoy!

You can read with Sam Lipsyte at a Rumpus event. All you have to do is write a piece of prose that uses a sentence from Sam’s new—completely awesome—novel, The Ask.

Scott McClanahan reads “Kidney Stones” in Atlanta

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ziUYE3Xaww4&

Video courtesy of Matt DeBenedictis.

Forwarding-video-to-me courtesy of Jeremy Schmall.

Sam Lipsyte interview by Paul Constant of The Stranger. It’s a good one. Q: This book in particular felt Elkinish to me. And I was wondering if you were thinking about him a lot when you were writing… A: Well, I think that his example is always with me. The notion of doing it with language—whatever you’re trying to do—of doing it with language and the example he set with his books is always with me. If you are in Seattle, Sam Lipsyte will be reading tonight at Neptune Coffee.

MOMMY ISSUES

The reward of relative fame for you as a writer is the ease with which others can casually diminish your life’s work. Which writer’s life obsession can’t be succinctly, correctly condensed into a single jealous phrase? This rotten fruit of your success lives forever.

On Zachary German’s “Eat When You Feel Sad”

[NOTE: The reviewer discloses several personal acquaintances, and asserts his unequivocal subjectivity.]

A Few Moments of Sleeping and Waking

.

When I was a kid my parents had a no-censorship policy on my reading material. The only exception they ever made to this rule was when I wanted to read a book that my dad was reading, called American Psycho. This was sometime in the mid ’90s, when the book was out of print. Dad had gotten it from a woman who worked in his office, who herself had found it on a website that specialized in hard-to-find books—probably the first person we ever knew who had used the internet to actually get something. I remember asking him about it, and that my interest was immediately piqued by his no-doubt abridged description. I remember asking to read it, and how, after much deliberation (which was baffling in itself, because I hadn’t meant “can I” so much as “when can I”) he finally told me, not without evident regret, that he would not let me read the book. “It’s not the content itself,” he said, “so much as that I don’t think you have the context to understand the content for what it is.” I must have expressed some outrage—this was unprecedented, after all—and he, concerned I might sneak a peek despite the ban, hid the book so well that we never found it again, even years later, when we emptied that house out and moved.

I started college in the summer of 2000, a few months after the film version of American Psycho debuted at Sundance. Now the book was everywhere. You could just walk into the store and buy a copy—with Christian Bale’s face on the cover, no less. I didn’t go see the movie in theaters, but I went and got the book. And I’ll tell you something—my father was absolutely right. Even at eighteen I didn’t really understand the book for what it was, namely the darkest of satires, mostly because I didn’t know enough about what was being satirized: Wall Street culture, the ‘80s in general, etc. So I took the book absolutely seriously, and treating it in this way made for one of the single most disturbing reading experiences I had ever had before, or have had since.

Zachary German would have been eleven years old the year American Psycho was released in theaters, and though I don’t know whether he saw the film before he read the book, it’s highly likely that a trailer for the film alerted him to the book’s existence in the first place. He would have understood going in, then, that the ultra-violence was a kind of cartoonish excess, and that the whole thing was to be understood (on some level) as a comedy, but he would have probably been still too young to fully grok how (or even that) the pathological cataloging of brand-names was meant as an extension of the central “joke.”

March 24th, 2010 / 3:56 pm

Who made who?

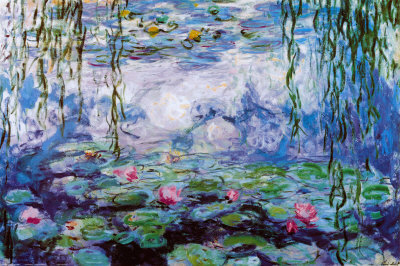

The “art as nature” vs. “nature as art” quandary may not be something we’ll solve today, which is fine, though artist Tim Knowles seems a little closer to the answer, or at least more keen on being the provocateur of such disparity. Is it harmony in entropy, or just taping pens to trees in a some sublime post-MFA bong hit? I don’t know, but I was immediately reminded of Monet’s waterlilies, whose tendrils of weeping willows seem to dance the surface of water in some attempt at recording their presence. Modernism was far less self-conscious, so we’ll leave it to Knowles to beg the question: What if trees, inherent with nature from soil up, were given the chance to flay their mark upon a most glorious human enterprise? What if the tireless human transcript of culture were merely incidental, just some random wind?

The “art as nature” vs. “nature as art” quandary may not be something we’ll solve today, which is fine, though artist Tim Knowles seems a little closer to the answer, or at least more keen on being the provocateur of such disparity. Is it harmony in entropy, or just taping pens to trees in a some sublime post-MFA bong hit? I don’t know, but I was immediately reminded of Monet’s waterlilies, whose tendrils of weeping willows seem to dance the surface of water in some attempt at recording their presence. Modernism was far less self-conscious, so we’ll leave it to Knowles to beg the question: What if trees, inherent with nature from soil up, were given the chance to flay their mark upon a most glorious human enterprise? What if the tireless human transcript of culture were merely incidental, just some random wind?