Craft Notes

The 2012 Realist Sex Novel Kerfuffle (a response to Blake and Stephen, involving also cowboys, Atlas Shrugged, and the Franzen/Marcus debate)

“Ho hum, I profess an interest in these cavorting sea nymphs only inasmuch as I can use them to allegorically comment on the Human Condition.”

Blake has stated, over at Vice, that he doesn’t want to read any more books about straight white people having sex. Stephen has stated, right here, that he is prepared to read many more novels about people fucking. There are substantial differences in these claims that we could pause to examine (“don’t want to read” vs. “am prepared to read”; “straight white people” vs. “people”; “sex” vs. “fucking”), but forgive me if I let those subtleties drop. Because I would rather observe that, if this is the scope of the debate, then it’s akin to one person saying, “I am tired of books about dogs, and no longer want to read more novels about them,” to which someone else replies, “I’m still willing to read some canine fiction.”

Recast in that light, it’s easy to see that neither person is right or wrong. How could they be? It is simply a matter of taste. One man has gotten tired of all those dog books. The other man is not yet so tired. The literary market, no doubt, will cater to them both. And perhaps, over time, demand for dog-free writing will grow, and drown out the pro-dog side, and the market will shift and, for some time, it will be hard to come by a copy of Marley and Me. (Here it might be helpful to replace “dogs” with some other thing, like vampires, or zombies, or alt-lit.) But through it all, one’s preference is perfectly free to steadfastly remain one’s preference. What’s not at stake, in other words, is the right to like whatever you like. The books you read say something about the person you are, and you should be proud of whoever you are! Display your chosen book(s) on the train to signal your affiliation with one of this nation’s many vibrant subcultures. Who knows? Another member of that subculture may spot you, in which case you can exchange nods, smiles, kisses! What’s more, today, thanks to the Internet, you can even make a list of the books that you like, then talk with fellow fans! (There are even web-sites devoted to this!)

Let’s try thinking instead about this argument in terms of genre. A new cowboy movie has comes out, and you and all of your friends go see it. Afterward, you’re wondering whether it’s any good or not …

One of your friends, Buster, thinks it’s good because he likes cowboy movies. Put a cowboy in any movie, and Buster is happy. Dude just likes cowboys! (“More cowboy!”) But Suzie dislikes the movie, because Suzie doesn’t like cowboy movies. (She says they’re, quote, “Yuck!”) She wouldn’t have gone to see this one at all were she not dating Buster. What’s more, both Buster and Suzie have very good reasons for liking what they like: as a child, Buster was saved from a flash flood by a cowboy, whereas Suzie’s father abandoned her and her mother to go drink whiskey and lasso steer. Well, it’s a puzzler! Buster and Suzie will no doubt argue long through the night, debating whether the movie is good or bad until the cows come home, or run free forever, but the only conclusion that you and I can draw from this is that they’re probably ill-suited as a couple (unless they turn out to be one of those couples that likes to always argue).

Your likes are your likes, and no one can tell you any differently. They can mock you, of course, and people might not want to date you. But that still fails to address the more pertinent question, which is whether or not this new cowboy flick’s any good. That question, we might now see, will require a different set of criteria, beyond the matter of like/dislike—a set of criteria other than whether all cowboy movies, a priori, are good or bad.

Whether an artwork is good or not is an entirely different question from whether you like the artwork or not. In other words, the quality of a work of art is irreducible to how popular it is. This is why you and I, who are of course very educated and sophisticated people, tend to distrust lists like this one (the one on the right), which ranks Atlas Shrugged as the greatest novel of the 20th Century, and lists like this one, which names The Shawshank Redemption as the greatest film of all time. The quality of a work of art cannot be equated with how many units it sells, or how many votes it receives in a popular poll. (This works both ways, though, mind you. Just because a book or movie is popular doesn’t mean that it’s not good.)

So what then does make an artwork great? It’s a complicated question, and a lot turns out to be at stake. Let’s look at the primary assumption lurking behind it. Perhaps there really is no such thing as a great work of art, no such thing as artistic excellence. Perhaps artworks are just like people, all of them wonderful and unique in their own special ways? Every pot eventually finds its lid, and every movie will eventually find its audience. You thought The Master boring and distant? Well, that movie just wasn’t meant for you; a different crowd will cherish it precisely for those reasons. Meanwhile, you loved Battleship because it was schlocky, and unintentionally funny? Well, bully for you!

In this view, the world where no artwork is any better than any other, “the World of Pure Difference,” art’s value turns out once again to be totally synonymous with consumer preference. As others have noted*, this is precisely what’s so boring about the much ballyhooed Jonathan Franzen / Ben Marcus debate. Franzen cried, “I’m tired of difficult fiction! Authors should write much easier books that are more about social problems, such as so many readers want!” To which Marcus replied, “Oh Franzen, you dope, you’re overlooking the fact that some readers do want difficult, experimental fiction!” Neither man is right or wrong as long as these are their stakes. From this perspective, easy-to-read social realism and experimental fiction with made-up words and jarring syntax can peacefully coexist, because the debate is not a debate but rather a question of reader identity. Which market or brand do you identify yourself with? Are you Team Marcus, or are you Team Franzen?**

In order to claim that an artwork is great, or even good, it turns out we need a more objective account of greatness—one that doesn’t rely on subjective and ultimately non-debatable qualities such as, “Do you like it?” We need criteria such that when we call an artwork good, we are not simply saying, “good for me.”

It should be obvious by now that we won’t be able to derive this criteria in terms of content—whether the book’s about dogs or fucking or zombies or straight white zombie dogs fucking. Nor will we be able to write off any genre—Western or horror or social realism or hallucinatory horror Western realism or experimental mishmash.

Well, do you see where this is all heading?

It turns out that a very smart critic, working almost 100 years ago, spent a great deal of time thinking about this very issue. I didn’t put his name in the tags or the headline so you would be surprised when I got to him, but it turns out that I’m once again writing about our old friend

And yes, dear God, I know I’ve already written a ton about the guy (here, here, here, here, here, and even more yet elsewhere), and so I won’t bore you by rehashing it all once more. But I will very succinctly summarize his relevance to this debate. What Shklovsky provides is an account of art’s value derived from how well we think the artwork both adheres to and deviates from its own tradition. The artwork exists in a context, against a landscape of other works. Audiences, thus, encounter artworks with certain expectations; they expect that the artwork to some extent will resemble related artworks. But the artwork, if it is good, also differs in some crucial way, and that difference (defamiliarization), when understood in relation to how the artwork also simultaneously conforms, is what determines artistic value.

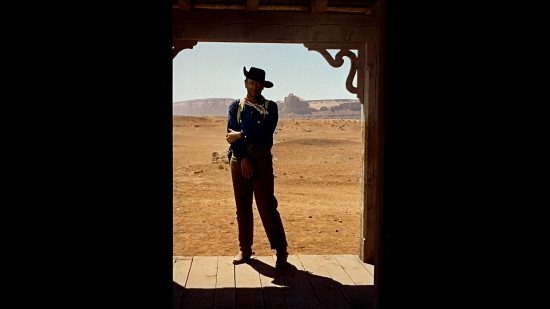

Which makes sense; we propose a cruder version of this argument whenever we say things like, “What’s good about that new cowboy movie is how it managed to be a real cowboy movie, but at the same time wasn’t predictable.” Or, as we might less crudely put it, “What’s so brilliant about The Searchers is that it’s at once a conventional Hollywood Western, and yet a critique of previous Westerns.” That The Searchers (1956) is a Western is not debated; it trades openly in its chosen genre, and yet it finds new ground for that genre (it revitalizes it). What’s more, its revitalization of the genre is itself a critique. As in so many Western movies, the hero, the cowboy Ethan Edwards, rides in on his horse and fights with Indians and restores the social order—he rescues Debbie from her captors, and returns her to her family. But the film differs by depicting Ethan Edwards as a brutal racist who, having accomplished his mission, is unable to then join the social order himself. Hence the staggering importance of the film’s most famous shot:

The innovation and its genre critique are intrinsically bound up with an adherence to canonical conventions. This shot makes no sense—it lacks its artistic import—if John Wayne is not wearing a cowboy outfit and standing outside the doorway of a log cabin, beyond which extends the Wild West.

This is why genre is no enemy of art, but rather the very occasion for artistry. This is why realism is no enemy of experimentation. This is why critics are wrong when they imagine only some types of art to be art (dismissing, say, any writing that employs Aristotelian unity, or privileging free indirect discourse above all other modes of writing). And this is why, artistically speaking, it doesn’t matter whether Blake or Stephen or me or you or anyone else we know likes the new autobiographically realist books about fucking, or doesn’t like those books, or doesn’t read those books, or cares or doesn’t care, because what matters in regard to any artistic value those books might have is how they relate, formally, to other books—other fictional autobiographies, other realist novels, other literary depictions of sex.

In other words, artistic value is formal value.

*I’m cribbing here from arguments made by Ryan Brooks and Walter Benn Michaels; indeed, I heard Ryan present on this very topic just last week. And before anyone gets too up in arms defending Marcus, understand this: in order for his rebuttal to Franzen to be something more than the promotion of experimental fiction as a niche market—i.e., “fans of experimental fiction are readers, too”—then he must propose some account of what experimental fiction is, and why such fiction matters even if no one wants to read it. In other words, he must defend experimental fiction on grounds other than Franzen’s own Contract Model.

Also, it will be obvious to anyone familiar with their writing that my overall argument here is indebted to Walter Benn Michaels’s and Nicholas Brown’s respective but related critiques of the reduction of art’s value to individual preference; for more along these lines, see Brown’s essay “The Work of Art in the Age of its Real Subsumption Under Capital” (which contains a brilliant reading of why Avatar is not art, but Terminator 2 is, in addition to wonderful observations on the White Stripes, Cee-Lo, Tropicália, The Wire, and more).

**One may certainly bemoan realism’s disproportionate market share, but that is a separate argument entirely from whether realism is or can be artistic. We’ve been inundated by zombie movies, and by superhero movies, but that doesn’t make films like Shaun of the Dead and Super any worse. If anything, the current popularity of those genres allows us to more clearly see the excellence of those two films, since they’re surrounded by so much pap. I mean, do you have any idea how many Westerns came out between 1956–62, the height of the genre’s popularity?

The IMDb records 5,892. As a culture, we’ve forgotten almost all of them. But we remember The Searchers. (And, no, it wasn’t so highly regarded at the time.)

Tags: ben marcus, blake butler, Christopher Higgs, genre, James Wood, jonathan franzen, Nicholas Brown, realism, Ryan Brooks, Stephen Tully Dierks, The Searchers, Walter Benn Michaels

If ‘The Searchers’ is the first western a person sees in their life, can its value (as described by you) be appreciated by that viewer? Or would it become a ‘new’ form in their mind, one that might then provide the basis for future difference & conformity?

This seems like a great question. Is genre required in order to judge art?

I’m always skeptical of attempts to critique art using a sort of Aristotelian approach (i.e. explanation based on empirical observations such as the genre discussion above). I think there almost has to be a Platonic element to artistic critique– an appeal to some metaphysical quality.

Hi AD,

I don’t think Blake is simply liking certain books and

Stephen is liking other books. It’s a

lot more than that and I think it’s important because it’s about how we

perceive/take/whatever reality. This is

about reality and how books approach reality.

Whatever else Blake is saying in his thing at Vice, it is against

realism (specifically white and hetero), but it is also not necessarily for

writing which is non-white and non-hetero – what Blake values, and clearly has

been valuing for just about forever if anyone’s really paid attention to him is

what he calls here “the beyond-human.”

For Blake, it seems, this isn’t a matter of he likes “the beyond-human”

better, but that the “human” is worn out, used up, boring. Now, this is just Blake’s perception, but it

is not just his “liking” one thing over another – he’s identifying a problem

with a particular mode. Stephen, on the

other hand, perceives that the human stuff is still important and necessary and

he’s not bored by it, it’s not used up to him, etc. And so, while this is just a disagreement of

perception, it is also not as simple as I like this better than that: Stephen

doesn’t see the same problem of overuse.

What I want to add, and seriously not to play the guy who’s

like “shake hands writer guys”, but really seriously, is that these are just

two sides of the same thing, the same reality.

Like, in zen we’d say that Blake is approaching the thing from the

absolute perspective, the intangible which is somehow also touchable and

explorable, though not through certain modes of writing; Stephen is approaching

reality from the relative perspective, the little ego, the self, which also can

be gotten at and explored through writing most of us “know” quickly and without

much decoding (and is, obviously, by no means inferior). To me, Blake’s really

asking us to step up and push into that absolute space, that void that is full,

that thing that is always there haunting along with us and rarely touched with

words. Or words rarely becoming it. Which, yes, please. But, I mean, it’s equally important to

remember that great-awe-space while also remembering the relative – because

both form and make each other. Really,

leaning too far in one direction leaves out a whole world, which is all of our

worlds, and so we have to look and write into each just as we write and are

each.

Yes!

I prefer “topic” to “content” in these discussions, because “content” in a story or novel exists because of its particular artistic arrangement in that story or novel. But yeah, I’ll never be able to wrap my mind around lazy statements that reduce books to their mere topics:

“I don’t want to read anymore books about white people having sex.”

Okay? What does that even mean? It’s like completely dismissing the purpose of fiction. Editors say these sorts of things all the time when discussing what they “like” and “don’t like” in the slush: “We receive too many stories about x, y and z.” Again, not only are these statements lazy, but they miss the point of fiction, which is scary, coming from people who are supposed to understand fiction. Whether or not a story’s topic is sex, martial discord, war, illness, etc. is beside the point, since no one reads fiction for mere topics. Harry Crews once said that a work’s topic is “what happens,” which is different than what a work is truly “about.” “The Old Man and The Sea,” Crews said, “is not ‘about’ fishing.”

I think one of the points AD makes here that’s worth repeating is that if someone criticizes work he doesn’t “like” and uses categorical language like “realism” or “realist” to express his distaste, he is obligated to account for the historical context of that category (and others like it). In the online lit world, you see people routinely make broad, sweeping generalizations about literary modes that are historically disengaged, and yet these people often get a free pass. There is not one kind of “realism” and much of the literature labeled “experimental” and assumed to be anti-realist is realist. The commonly perpetuated notion that realism is linear and always Aristotelian is simply wrong. History is replete with examples that prove otherwise. People need to stop making so many broad generalizations about literary modes and genres. How we discuss literature is a much bigger problem right now than Franzen/Marcus binaries.

I think one could evaluate a western ‘as a western,’ which would require observations on the genre. But to evaluate a genre itself, one would have to appeal to something higher, something approaching the universal. (Or just admit up front one is talking about nothing but one’s own personal taste.)

no,

i mean, nobody’s obligated to do anything. still though: i think it’s

pretty clear what types of books blake is finding problem with. in the other thread about the stuff he gives an even clearer description. also,

yeah, the commonly perpetuated notion that realism is linear is wrong, sure.

completely agree. and that making sweeping generalizations isn’t

all that helpful. but, to me (that saving phrase), blake is saying some

real shit and so is stephen. and so is AD (oh, and AD, i mean, your post

rocks), but i think AD kind of reduced the issue to “liking” at the beginning of his post a bit too easily. that’s all.

[…] = ''; } Modern Home accents – Taking your home decor and furnishing to the next levelThe 2012 Realist Sex Novel Kerfuffle (a response to Blake and Stephen, involving also cowboys, Atlas…Modern Home accents – Taking your home decor and furnishing to the next levelThe 2012 […]

In literary discussions, people are obligated to grapple with the historical ramifications of the literary categories (like realism) they interject.

Yes, bad realists privilege reality over the imagination, and yes, this is boring (stating the obvious), but this is a separate issue from whether or not one “wants to read less books-about-x-y-z,” since there are enough examples of “realist” writers who privilege the imagination over mundane reality to counter the notion that Blake has identified a trend. The writers in the first category ultimately fail because they are bad artists, not because they are “bad realists” and “realism is [somehow] responsible for perpetuating bad art.”

i’m not talking about realism. i realize i said the word “reality”, but i did really mean that, not realism. i realize other people are arguing about the literary genre and period realism, but i’m not. i am in total and complete agreement with you: yes, the literary period known as realism, yes, i’m totally with you, is something completely different from writing about “reality,” yes. all i tried to do here was to distill what i felt was the essence of two interesting perspectives/perceptions about the writing world. i don’t know how to explain to you what “beyond-human” means (that’s kind of the point, that it can’t be explained, and only in certain modes of discourse/language (try some Dogen) is this darkness into darkness, the way of us all, clarified), but it to me it has a very clear feel and i get exactly what blake is getting at and at the same time i understand stephen’s impulse to defend something he values, a certain kind of writing, etc.

Fair enough. I admittedly read AD’s post as part of an ongoing conversation, not just as only a response to Blake Butler. The “unhuman” stuff has always bothered me because it seems to suggest that ugliness, darkness, weirdness, etc. are unhuman–that when Chris Higgs posts pictures of murdered and raped women they somehow represent the “unhuman” when anyone who has lived in the world knows that such images are as human as images of people smiling and holding hands.

No, I won’t forgive you that, and it shouldn’t be re-casted in that light. It’s irresponsible.

The above response begins with the same argument people who write “I’m not into black guys, not a racist thing, i’m just not” on their OKCupid profs vibe on. It then proceeds into an argument for aesthetic relativism that is at best, placating and more truthfully, equivocating. It gives no acknowledgment to any of the actual consequences such a perspective can have on people who don’t have the privilege to treat art so academically: those who are marginalized – NAY, oppressed – by the tides and trends of genre.

“what matters in regard to any artistic value those books might have is how they relate, formally, to other books”

how bout how they relate, formally and otherwise, to LIEF

Adam D Jameson – I have to say that I agree with the commenter alanrossi on the post, that neither Stephen nor Blake (or maybe Stephen, but defineitly not Blake) were/was making arguments about “liking” things or Taste. Discussion of aesthetics cannot be reduced to this, just as Blake’s piece can’t be reduced to its title (which is, in fact, quite different from its thesis). And the methodology for assessing artistic merit that you propose, while elegant, falls short, as it is a closed system – if the merits of a work solely from it’s similarity and deviance to other in-genre works, or even extra-genre, there is no room for the non-literary to even inform literature. Ergo, the kind of “realism”, or the “real”, or “authentic”; or “human(ist)” that Stephen is arguing for are impossible, as their referents (the “real” or the “human”) can’t even come into the equation. Which seems really absurd. To return to your Cowboy analogy – if their hadn’t been a historical West, and if that hadn’t been mythologised, and if their hadn’t been issues of colonialism, and racism, and violence and the like, then The Searchers wouldn’t have been possible. And it is those extra-formal qualities which make it so successful as a film. Sure, they are part of the “deviation” from generic norms, but they cannot be *reduced* to such.

Blake was saying that he wanted something more than what we can call “humanist” literature, or neo-realism, or something like that, and Stephen made a really quite eloquent case for Humanism – but your evaluation of both of their positions as simply matters of taste seems to discount not only the basis for their arguments, which are both extra-literary referents or effects (in Blake’s case I would hazard to say a monstrous numinous, and in Stephen’s the material of the everyday) – and also doesn’t account for what is probably underpinning both writers’ positions, which is the relationship between aesthetics and a kind of artistic ethics (there’s a hell of a lot of talk of obligation here, and privilege, and humanism, which all have their roots in ethics).

And if one brings in ethics, then it very quickly stops being just and equivocation based on taste, and one person “liking” one thing, and another another. And there’s even more that can be said about the politics implied by Blake’s piece – the “straight white people fucking” seems to me to be a kind of sigil of white male hetero middle-class-ness as the normative paradigm of The Real or The Human in literature. No one seems to have picked up that ball and ran with it. Which is either odd, or really expected (because it’s kind of scary). I don’t know, and can’t really say much about this, but my general feeling is that the majority of my favourite fiction writers of the last 20-30 years of so have all been either queer or women (but then again, I read probably 10x as much poetry as I do fiction, so I can’t really be at all authoritative or objective when it comes to such). I also feel like there’s a really strong burden of sanity pressing down on a lot of fiction. I’m not sure exactly what I mean by that, but it feels like the sky is really heavy inside The World Of Fiction somehow. But now I’m probably not making sense.

oh, no, i don’t see what blake means by beyond-human to be anything necessarily related to ugliness, weirdness, etc, but more like a different way of penetrating reality or like a reality that is always there that we rarely go into. darkness-into-darkness is taoist phrase/translation for this thing which cannot be explained or pinpointed with words but which some art goes into or is. anyway, must turn off brain now.

I had a difficult time following his article’s thesis. The first few points were interesting, but then the piece devolved into incoherency. I guess I read too much like a straight white male.

I think he wanted to write a fishing story.

I think one can agree with AD, as I think I do, while also recognizing that some of the reasons we have for disliking certain subjects or genres or traditions may be moral or philosophical reasons with real weight, and that in the grand scheme of things, these considerations may be more important than purely artistic or literary concerns.

[…] by Salvatore Pane Blake has stated, over at Vice, that he doesn’t want to read any more books about straight white p… […]

I don’t think the difference between evaluations of quality and sensitivities to pleasure is “entire”.

Each is founded partly in intersubjective and communicable experience–you can talk, to some limited degree, about where you differ with another evaluation of quality and discernment of pleasure.

There is a linguistically mediable concrete shared horizon of the experience of an evaluation of quality and a linguistically mediable concrete shared horizon of the experience of a measure of pleasure.

Where the terms for these evaluations and measures are the same, the questions attached to them are similar.

‘I enjoy slow movies with relatively few relatively long takes.’ –that registers a criterion for pleasure, which, cross-referred to a few or to many other criteria of pleasure, is also evaluative of quality — not in some purely ‘subjective’ sense, but dialogically. ‘Yeah, usually I like those movies, too, but these performances were so wooden!’ or ‘Oh, I’m easily bored by that static aesthetic, but this movie was made of images so beautiful that I was engaged all the way through.’

I don’t think the conversations of what one likes and what one thinks is good are completely walled from each other–any more than each is walled from other people’s determinations.

The interaction between Blake and Stephen might seem ‘past’ each other: Stephen supporting expression of the din of direct experience, as (somehow) exemplified by “autobiographical fiction”, and Blake preferring that characters’ “egos” be not so disilluminative of ‘world’.

–but they discover common ground pretty easily: Tao Lin. –and in terms both evaluative of quality (without dogmatic imposition of universality) and mutually intelligible registering of pleasure (‘yay’).

expression versus impressedness

you happen versus you are happened to by

one measures ‘all’ things versus things parcel one

The best art to me is more about forgetting what it is to be human. There is the type of art that does this without even getting to the level of human (mass entertainment). I’m talking about that transcends, in a sense: i mean, loosens the grip of neurosis – I mean actually does this. Vast majority of “realism” is neurosis squared, and made by very neurotic people. Which is fine, a welcome addition to the whole project, certainly.

I enjoyed this and honestly was with you until the last two sentences, when your argument suddenly…petered out, for lack of a better term: “Because what matters in regard to any artistic value those books might have is how they relate, formally, to other books—other fictional autobiographies, other realist novels, other literary depictions of sex. In other words, artistic value is formal value.” This seemed to me like the starting place of a conclusion that went unwritten. Perhaps you feel you’ve covered it sufficiently in other posts, but I’m not willing to open ten new tabs to find out. What do you mean here by “formal”—obviously something different from what most of us mean when we’re talking about the craft of structuring writing? And, in the sense of “who gets to speak and why”—isn’t it politically of interest who gets to decide “how [books] relate, formally, to other books”? Not complaining, because I’m a fan of any literary critical piece that manages to drag in John Ford so sapiently. Just wishing you’d completed the thought you’ve here begun.