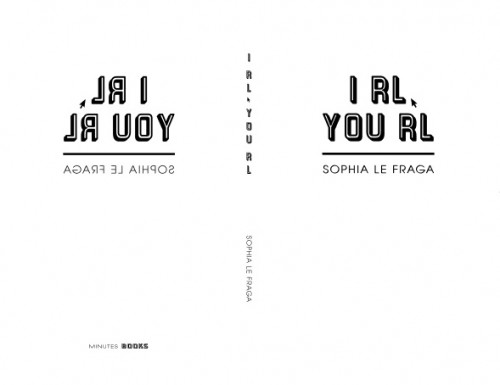

An Interview with Sophia Le Fraga

Sophia Le Fraga’s I RL, U RL has just been released from Minutes Books.

Andrew Worthington:

Where are you right now?

Sophia Le Fraga :

I am…FUCK…I am at work, at the Hearst Tower.

AW:

What’s your job?

SLF:

I’m a copywriter and editor at this digital ad agency.

AW:

How’d you get that job? What sorts of ads do you do?

SLF:

Well so, I studied Linguistics at NYU and when I graduated, I was just all over the place, traveling up and down the California coast kind of like aimlessly, and one day this guy called me and was like, “oh NYU said that you could tutor me in Syntax and Semantics”, and I was like, “Yeah sure” and he was like, “ok be in touch when you’re back.” And when I got back, I hit him up to tutor him a couple of times a week, and when we met he was like, “I’m the SVP of this ad agency, do you want to just like… work for me?” And I was like, “Well it’s not like I’m doing much of anything else…” So that’s how I ended up here. I do all kinds of ads, from skin care stuff to like cable and internet stuff to banks and cancer treatment centers…it tends to be…an eclectic bunch.

AW:

Did you take writing classes when you were in college? Or was writing something you did on the side sort of?

SLF:

Yeah totally. NYU didn’t offer a Creative Writing major but I pretty much took enough credits to double up. I took a lot of poetry, some fiction, and for two years, did an independent study with Rob Fitterman on “Poetry of the Avant-Garde”. I feel like writing was always what I wanted to do, but I wanted to have the background in Formal Linguistic to kind of… better understand what I was doing.

*Linguistics

AW:

Can you describe some of the ways you may go about writing poetry? How did you compose I DONT WANT ANYTHING TO DO WITH THE INTERNET?

SLF:

Well, so, I DON’T WANT ANYTHING happened after I submitted a sort of “open call,” asking everyone I knew on Facebook, Twitter and e-mail if they wanted a “poem”… and depending on what medium they responded in, I took from their feed, or their wall, or their e-mail and gave them each a poem of sorts, using only their language. People love to hear themselves talk.

AW:

So I guess no one was upset with the poem you made for them, then?

SLF:

No, of course not! All I gave them was a word salad of whatever they’d already shared on the web.

But that’s not to say that people haven’t been upset with me. That’s all pretty extensively catalogued in “H8M8” [a section in I RL, U RL].

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 2: What is a constraint?

OK, back to this. In Part 1, I traced out how in conceptual art, the concept lies outside whatever artwork is produced—how, strictly speaking, the concept itself is the artwork, and whatever thingamabob the artist then uses the concept to go on to make (if anything) counts more as a record or a product of the originating concept. (This is according to the teachings of Sol LeWitt, as practiced by Kenneth Goldsmith.) Thus, we arrived at the following formulation:

- Artist > Concept > Artwork (Record)

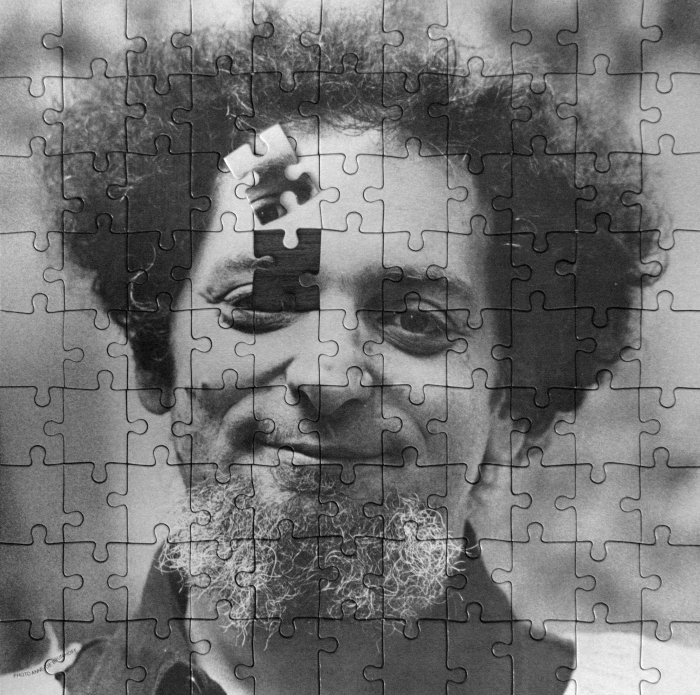

Now, I’m not going to argue that every conceptual artist on Planet Earth works according to this model. But LeWitt’s prescription has proven influential, and continues to be revolutionary—because choosing to work with either a concept or a constraint will lead an artist down one of two very different paths. To see how this is the case, let’s try defining what a constraint is, aided by the Puzzle Master himself, Georges Perec . . .

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 1: What is a concept?

Sol LeWitt: “Wall Drawing #1111: A Circle with Broken Bands of Color” (2003, detail). Photo by Jason Stec.

[Update: Part 2 is here.]

I wrote about this to some extent here, but I wanted to expound on the issue in what I hope is a more coherent form. Because I frequently see concepts confused with constraints, and the Oulipo lumped in with conceptual writing. For instance, this entry at Poets.org, “A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry,” states:

One direct predecessor of contemporary conceptual writing is Oulipo (l’Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a writers’ group interested in experimenting with different forms of literary constraint, represented by writers like Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, and Raymound Queneau. One example of an Oulipean constraint is the N + 7 procedure, in which each word in an original text is replaced with the word which appears seven entries below it in a dictionary. Other key influences cited include John Cage’s and Jackson Mac Low’s chance operations, as well as the Brazilian concrete poetry movement.

I would argue that the Oulipo, historically speaking, are not conceptual writers/artists—although it’s easy to see how that confusion has come about, because the Oulipians have proposed some conceptual techniques, such as N+7 (which I’d argue is not a constraint). (Also, it’s each noun that gets replaced, not each word.)

What, then, distinguishes concepts from constraints? And why does that distinction matter? In this series of posts, I’ll try answering those questions, starting with what we mean when we call art conceptual.

Another way to generate text #5: “synonym clusters”

This one’s easier to do than the dictionary clusters, but similar in principle. First, you look up a word in a thesaurus and collect every synonym for it. Then you write through that cluster of words.

Let’s try it with “bald.” Synonyms include:

bald, baldheaded, bare, bare-bones, bareskinned, barren, bleak, clean, denuded, depilated, disrobed, divested, dour, exposed, glabrous, hairless, head, in one’s birthday suit, naked, nude, peeled, plain, primitive, rustic, severe, shaven, shorn, simple, skin head, smooth, spare, spartan, stark, stripped, subdued, unadorned, unclad, unclothed, uncovered, undressed, unembellished, unrobed, vanilla

(To get this list, I copied the first three entries at Thesaurus.com into Notepad, then deleted all the extra text, then arranged the synonyms alphabetically in Excel, then deleted all the duplicate entries.)

Now let’s write something with that:

I slept with a bald woman once.

Theory of Prose & better writing (ctd): The New Sincerity, Tao Lin, & “differential perceptions”

In the first post in this series, I outlined Viktor Shklovsky’s fundamental concepts of device (priem) and defamiliarization (ostranenie) as presented in the first chapter of Theory of Prose, “Art as Device.” This time around, I’d like to look at the start of Chapter 2 and try applying it to contemporary writing (specifically to the New Sincerity). As before, I’m proposing that one can actually use the principles of Russian Formalism to become a better writer and a better critic.

Another way to generate text #3: “dictionary expansions”

A Pan-English Dictionary (for readers of Harry Mathews’s The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium)

And while on the subject of reposting literary resources: here’s a Pan-English dictionary I made for the benefit of anyone reading Harry Mathews‘s early masterpiece, the epistolary novel The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium.

And while on the subject of reposting literary resources: here’s a Pan-English dictionary I made for the benefit of anyone reading Harry Mathews‘s early masterpiece, the epistolary novel The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium.

Odradek presents the correspondence of newlyweds and amateur sleuths Zachary McCaltex and Twang Panattapam. Separated by the Atlantic, they exchange letters in which they “try to trace the whereabouts of a treasure supposedly lost off the coast of Florida in the sixteenth century, while navigating a relationship separated by an ocean as well as their different cultures.”

Twang, who hails “from the Southeast-Asian country of Pan-Nam,” peppers her letters with snatches of her native language, “Pan.” Fortunately for her husband and the reader, she also translates it on the spot. I’ve collected all of the Pan and its English equivalents and presented them below.

Cliché as Necessity (Birthing Innovation)

Every time I’ve said something nice about Drive, someone has responded by calling the film “clichéd.” Well, I intend to keep saying nice things about Drive (as well as other artistic genre films), so let’s take some time here and now to address that criticism, demonstrating how even when certain material or situations might be clichéd, the artist can still find occasions for artistic expression. Indeed, I want to go so far as to suggest that clichéd situations often provide artists with some of the best opportunities for innovation.