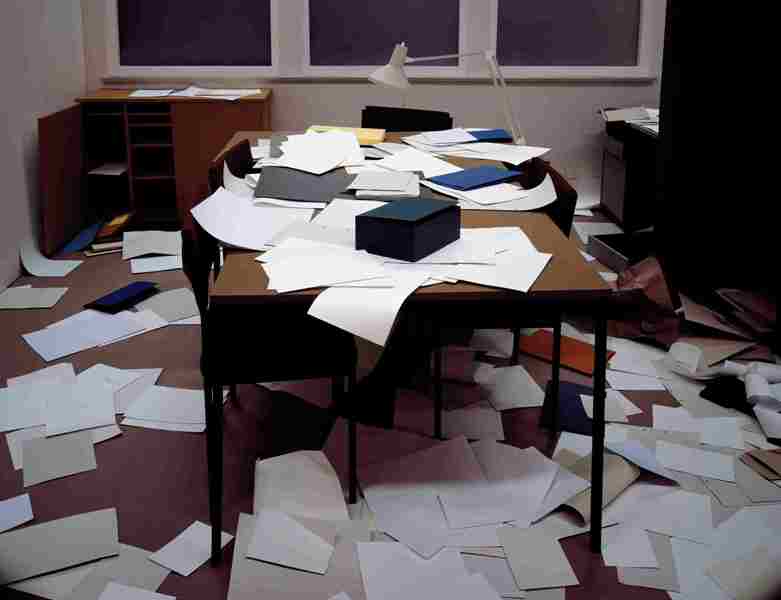

Vice’s “DOs & DON’Ts,” revised by someone who is not high or cool

via Vice [original]

Sorry, sorta annoyed by Vice‘s “Do and Don’t” series, in which urban fashion is qualified under so many layers of kitsch and irony that the DOs often seem provocative for its own sake, and somewhat unbelievable. I try to appreciate this, as some social commentary, far more than the Dos and Don’ts of corporate fashion glossies like Us and People, yet it feels like Vice here is the emperor chasing our image with mirrors, telling us of special fabrics only they can see, until we too see it. Be careful: punk sounds a lot like drunk, and only one can be dissent. Dear people, there’s always a sale at Ross. It’s okay to be invisible.

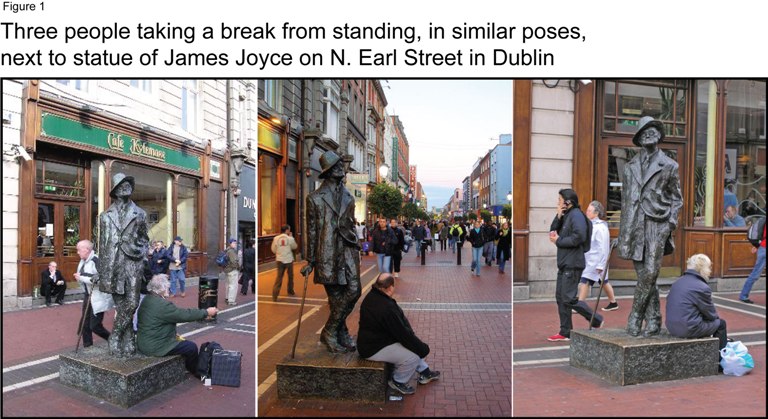

Examples which might explain James Joyce’s love-hate relationship with Dublin

Finnegans Wake is super tiring, and for some, so is James Joyce. But come on people, North Earl Street doesn’t look so bad. History is made to be forgotten, and for folks to sit on. For birds, to shit on. Short of a rhyme for immortal rigamortis, just give us reason.

Wi-fithering Heights

What the hell, is that a laptop by Emily Bronte (d. 1848)? I assumed it was photo-shopped, but upon searching online, every version I found (from reliable non-satirical websites) shows the same laptop. It also looks like she’s fingering (probably should’ve used another word) her phone.

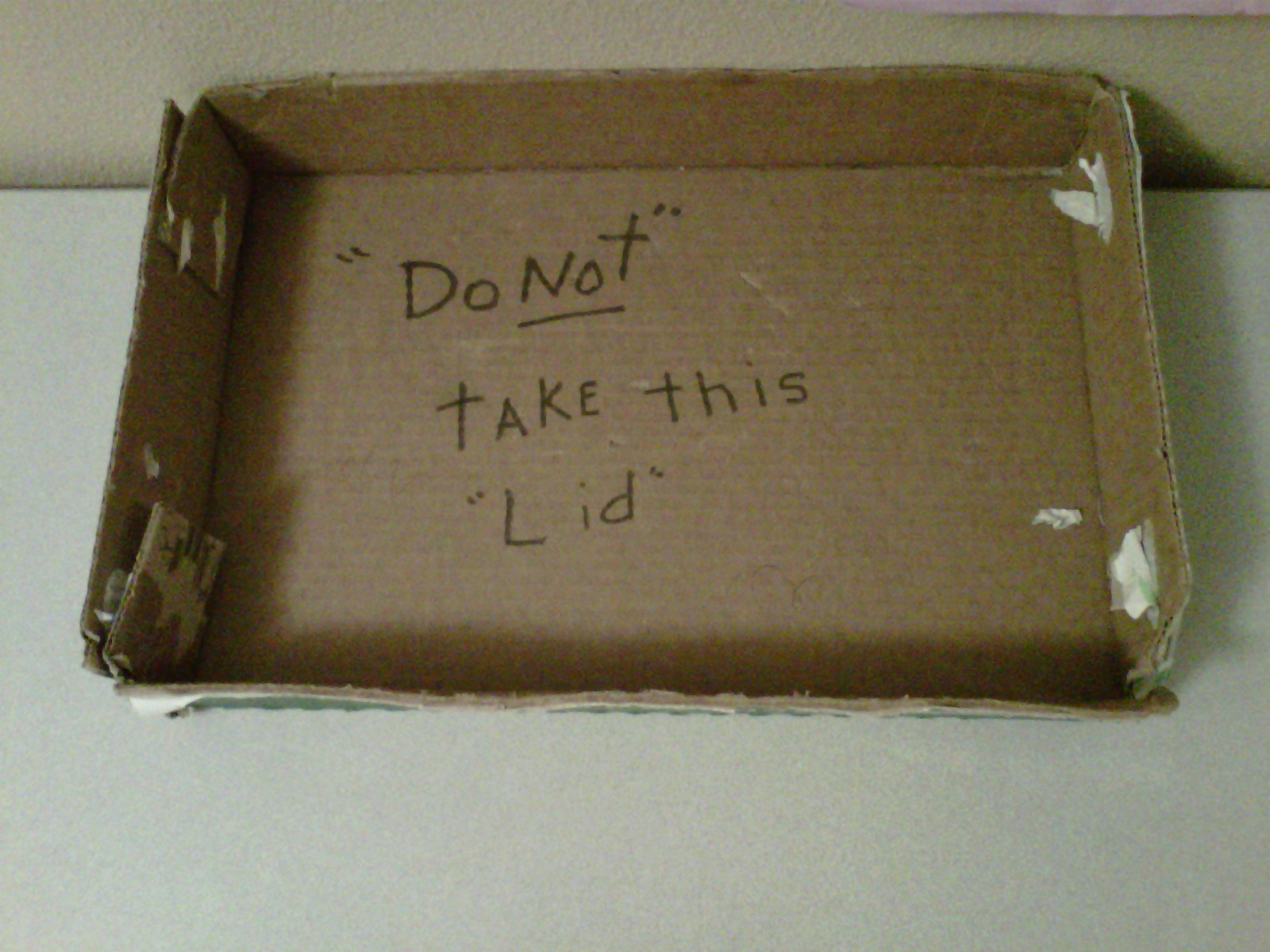

“Htmlgiant blog post about the use of quotes”

The “Blog” of “Unnecessary” Quotation Marks is a celebration of obtuse and/or excess rhetoric, offered as utilitarian measure by various small-time vendors. I appreciate the joyous examples, given their contrast to the more affected self-conscious use of quotation marks used by writers today. It gets me thinking about the intent of syntax: where meaning is augmented, or even fractured, by the play of the writer. In “Do Not” take this “Lid”, it seems they are conceding to the questionable function of said “Lid,” and asking for liberty in calling it such a thing. “Do Not“ may be quoted to suggest an awareness in the cliche, or maybe in solidarity to it. Notice only the appropriated terms are capitalized, as if the true disposition of such assertion were of a more modest nature. I’m probably reading too into this, I just like thinking about the minutiae of sentences often taken for granted.

We are here

It’s odd that technology’s default backdrop is often nature, as if an apology, a nod to how things were. Windows XP’s “bliss” wallpaper shows a rolling meadow seen through faceless, almost disembodied eyes. Apple, always listless and self-conscious in their designs, offers us, with the iPad, a clear lake at dusk; I wonder if it’s just me, or if “dock” — the term Apple uses for the row of applications at the bottom — in the foreground is a playful pun operating also as a dock on a lake. Or maybe it’s not dusk but dawn, wake up time for the early risers, those people with severe jobs and complicated calendars.

I once pointed to my iPhone in Google maps and said to my wife during a hike “we are right here,” to which a passerby scoffed “no, you are here,” demonstrating with his arms the vicinity of reality (I guess everyone is a Zen master). He probably went home to regale to his wife a story about some dork on his iPhone who could only find his ass were it an app. It’s useless to look at porn on your iPhone: the lovers are too small. If you’ll grant me an aphorism, let it be that.

I’d like to think I could jump into Apple’s lake anytime, dusk or dawn, like a seal meets Thoreau. Let me just block out the image of Jason Voorhess comin’ to get me, which is why I never camp, no matter what Sontag has to say about it. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, sigh, youtube and wiki it, respectively, you useless bastard.

Charles Lavoie offers an alternate, if not more compelling, line for The New Yorker‘s caption contest illustrations, which may point to a redundancy of logic in the latter’s humor — that of minor transgressions in inopportune moments.

Op Ed on Eds

I get confused by all the kinds of editors there are. It seems that journals that take themselves really seriously tend to have a bunch of editors. I don’t know that much about publishing, so maybe there’s a guideline, but to me it just seems like a bunch of people calling one another fancy names. What follows is my guess about what these types of editors do.

Editor – this guy (sorry, I imagine a dude) doesn’t read submissions; he might not even read the journal when it comes out. He just calls his friends on the phone to solicit their writing. He likes to say “I split my time between New York and [some other city].” This guy is famous and he rocks.

Executive Editor – this guy is old, and went to Princeton in the 50s. He doesn’t have an email account; doesn’t even know what twitter is. He just goes to the bank and transfers money and writes checks. He lives by a lake, but cannot swim.

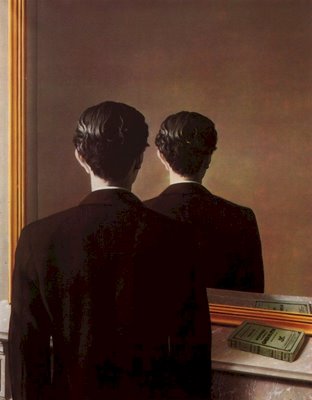

On semiotics

The best way to describe a cat is to use the letters c, a, and t. Every word contains a world, and some wonder why we still write. Two arms and a head is shorthand for “man drowning”; lol is an acronym for “laugh out loud,” usually used glibly as hyperbole. When semiotics meets semantics, there is a surreal incident of uncanny humor — an illustration with its own inverse reaction embodied in it. Insert a hyphen in 911 and you have 9-11, the latter date on which the former number was no doubt dialed. As we move along, as the mutt of history and words grows up, let us know when to laugh, when to laugh out loud, and when to remain silent.

[image via fail blog]

On “Phone by Darby Larson,” with digression

“Phone by Darby Larson,” by Darby Larson, in the current issue of The Collagist, is one of the most refreshingly original pieces I’ve read in a while. The fading sequence of gray fonts mirrored at both beginning and end make the words, or ‘tips’ of the story, receed along an arc into visual space, as if the story itself were a giant sphere — a circular notion aptly mirrored in the jumpy, overlapping, entropic, and ultimately symmetrical narrative. Here, Larson (also per Abjective’s editorial fancies) is not just interested in telling stories, but writing them. In my mind, the two are different: the former merely a transcript of what one might say aloud to a spectator, the latter being actively aware, pensive even, of its ‘wordness’s’ function, capacity, limitation, and artifice. Oral history is fine, but I prefer writing that is seen, upon which, in this case, the structure looks like an almost palindrome, with wonderful tiny placed errors.

“Phone by Darby Larson,” by Darby Larson, in the current issue of The Collagist, is one of the most refreshingly original pieces I’ve read in a while. The fading sequence of gray fonts mirrored at both beginning and end make the words, or ‘tips’ of the story, receed along an arc into visual space, as if the story itself were a giant sphere — a circular notion aptly mirrored in the jumpy, overlapping, entropic, and ultimately symmetrical narrative. Here, Larson (also per Abjective’s editorial fancies) is not just interested in telling stories, but writing them. In my mind, the two are different: the former merely a transcript of what one might say aloud to a spectator, the latter being actively aware, pensive even, of its ‘wordness’s’ function, capacity, limitation, and artifice. Oral history is fine, but I prefer writing that is seen, upon which, in this case, the structure looks like an almost palindrome, with wonderful tiny placed errors.