Art Balls

It’s really cool for an artist right now to make like a lot of one thing (in this case balls) and fill up a gallery with that thing. The phrase “excessive redundancy as aesthetic vapidity” comes to mind, which is why I don’t get paid by the idea. And you are to understand that the question “what does it mean?” is rather unsophisticated — ungenerous, even petty — so you kind of just accept it and try to enjoy the inherent form, or like the “recontextualization” of it, like how you don’t go to a gallery expecting somewhat scatological balls in huge piles, and so the artist is like changing your view, or mind, about what it means to walk into a gallery and be confronted with these large plastic cartoon-y yet alienating balls which are ridden with meaning by their very meaninglessness, perhaps even commissioned by the gallery, or a bored patron, and made by factory workers overseas, shipped in a kind of economic slave ship, and finally assembled in the gallery by the artist himself and his interns and/or art friends, on every weeknight the week preceding the opening, nice asses on floors in uncomfortable jeans, half-eaten burritos or falafels sharing the floor with two tepid six-packs, jewels of condensation sliding down, the gallery director in her brownstone crackling knees as she kneels down to place dog food into the dog bowl for her dog named after a Japanese film she saw when she was in love once.

Britney Crying

On Thursday May 18, 2006, Britney Spears, then 24 years old with 8-month-old son Sean Preston Federline, was photographed in a restaurant between the Ritz Carlton and New York-Presbyterian Hospital, crying. Perhaps it was Postpartum, or the Paparazzi, or just the onset of life formerly dodged by her pigtail’d statutory look. The resolution is grainy, captured by an unfair stranger who made a lot of money that day. The “extra” glimmer in her eye — not of the cornea, but a welled tear — may be described by a solid square pixel, void of knowing what it was portraying, the incandescent camera’s flash hitting a bulbous mound of saline. The celebrity photo, taken in one moment forever gone, much like painting, prospers by its sole uniqueness as it nails itself into some history of who we are, what we want. Britney may be a gross American, but she may also be our first sacrificial lamb. (One imagines likely contemporaries Avril Lavigne, Lada Gaga, and Ke$ha as being less sad, perhaps more complicit.) A virgin with stretch marks is obviously not a virgin anymore. As for the girl with the pearl earring, her own glimmers painted in by a dead man, she lives somewhere in a dank gallery inside The Hague, a quick train from where kids with new passports go to get high.

Contributor Party

Erik Stinson

Corporations are the new angels of America, letting go in aluminum bathroom stalls, those mirrors of our spiritual disguise. Bagel holes were the voids in our lives, filled by pop-up ads, punctured by five inch heels propping up the advertising interns “doing” Soho for lunch. Arugula salad. In my New York office painted eggshell white and Sharpie marked with cartoon allusions, amidst the European glossy mags on which my foggy semblance prevailed, I could feel the pulse of my enormous member in my palm. It felt like Miami during high noon, the relapse of a USB drive containing a .pdf novel. The domestic beer in front of me was eventually outsourced by the neopolitics of ironic ingestion, sprayed outward into R. Mutt’s urinal moments after my pastrami sandwich made by the last Zionists of West Village. The CEO listened to a calm ocean with his Sony walkman. I got promoted.

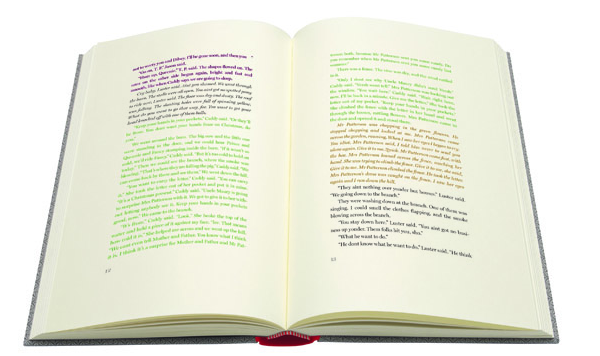

Faulkner in Color

In 1929, at the time of its publication, William Faulkner said “I wish publishing was advanced enough to use colored ink” in regards to his vision for The Sound and the Fury, specifically, that each of the many intricately layered timeline threads would be printed in different colors. He resigned to using italics in order to address the past, which was rather confusing, given the blunt binary of italics vs. roman text, and the myriad tiers of pasts therein. Reading Faulkner, I always ignore the italics, as part of the allure in reading him is the palpable confusion of memory — the contradictions, oversights, strange overlaps — as similar to the very way we remember, or mis-remember, our actual experiences. The initial modernists (e.g. Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner) seemed to imbue their books, inadvertently or not, with living matter: the tongue of alliteration; the pulse of cadence; the corrosive and unreliable mind; the insecurity of communication; the unruly heart, the very messy things though which we lived, rather than simply read. Eighty-three years since its publication, English publishing house Folio Society is publishing the book as the author intended. It’s gorgeous, $345 dollars, a promised delivery conveniently in the light of August.

Sentimental Education

1990

Jani Lane, the lead singer of Warrant, was found dead from acute alcohol poisoning at the Comfort Inn in Woodland Hills, California on Thursday August 11, 2011. He, to those who would bother Google imaging him, would seem visibly more and more depressed in correlation with his age, perceived failure, and weight gain. Warrant’s sophomore effort Cherry Pie (1990) topped at No. 7 on the The Billboard 200, though their biggest hit was off their debut album “Heaven,” a place which Lane promised his groupies wasn’t too far away. The titular first single “Cherry Pie” featured model Bobbie Brown, who was dating one of the Nelson brothers (of Nelson, the band) at the time, with whom she broke up in order to be with Lane. One suspects Brown cheated on Nelson with Lane, and laconically dealt with relationship logistics later. Starfucking has always been cosmic-like, explosions of gas in a black universe. Subsequent facial surgeries have rendered Brown severe looking, which makes me, this petty memoirist, happy. In an interview with VH1, Lane said, in regards to “Cherry Pie” being his legacy, “I could shoot myself in the fucking head for writing that song.” You can see a tear well up in his eye.

I wrote the parts graciously left anonymous on page 4 in Cybersex by Marie Calloway. Unedited screenshots of our correspondence — some of which are corroborated in the original publication, others which implicate her lies, and my naïveté — follow after the break. Of course, this is rather embarrassing on my end, given the glib sexual graphic nature herein. May this be in defense of her other hopeful suitors who were likely equally manipulated.

Finding Rothko

On February 25, 1970, Mark Rothko was found dead in his studio covered in blood with a razor next to him. Forty-two years later, his death would be used somewhat manipulatively to garner attention from likely readers. Last weekend, the author would have been reminded of our painter upon seeing noncommittal blotches of paint applied with a roller around his neighborhood. He would have taken pictures, perhaps even instagrammed them, but didn’t want to be one of those assholes taking pictures of urban oddities for artistic purposes, so he retraced his footsteps in Google streetview later on that week, at work, to find said moments — though he would admit that this notion was not entirely his, pointing to a short documentary The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal (2002), which proposed similar relationships between the subtleties of abstract painting and the residual inadvertent inconsistencies in tone and hue caused by aggregate layers of similar-ish paint in the covering of graffiti. And it would not be hard to begin talking about class, how some marks are cordoned off in museums, whereas others are left to perish or prosper in public entropy. (Some socioeconomically disenfranchised kids asserted power in the true democracy of space: on the side of a building, for all to see their name, or the gang to which they belonged. Or, they are simply punks from good families, and the immigrant worker most likely tasked with a paint roller and approximate bucket is the silenced subordinate.) It’s funny how we place both the Cross and painting on the wall, embarrassed — at least I am — at the loud hammer upon the nail from which they hang. I majored in Art, and minored in not being realistic. Rothko’s manhood was left impotent by an aneurism, his other manhood — what we’ll call “legacy” — left inside his eponymous chapel by a Texan millionaire giving philanthropy a go. The Rothko Chapel is non-denominational, as no one wants to argue with the dead. Rothko was involved in its design, wanting it windowless, save an unblinking skylight above. Perhaps those dark purple paintings, the slow bruise over a career that lacked the egoism of his peers, retained of any form save the canvas’ dimensions themselves, were to be windows elsewhere.