INTERVIEW W/ JAMI ATTENBERG

Jami Attenberg’s new novel The Melting Season just came out from Riverhead, and she’s reading tonight at Word Bookstore in Brooklyn. The novel’s about a woman named Moonie Madison whose husband has a micropenis, and she has some adventures involving lost women, dangerous men, Prince impersonators, and Vegas. The writing is really good and the book is Jami’s best so far. (I reviewed her first novel, The Kept Man, when it came out, and her collection Instant Love is excellent.) I asked her some questions about the book and about writing sex scenes and what kind of musician impersonator she’d like to hook up with.

READ MORE >

Carve

Here is an interview with Carver biographer Carol Sklenicka at The Economic Times, India’s leading business newspaper. This website is quite the thing, especially for the epileptic. It is cluttered and jangly and tries to sell you every square inch of someone’s soul or something. Just focus on the interview.

Here is an interview with Carver biographer Carol Sklenicka at The Economic Times, India’s leading business newspaper. This website is quite the thing, especially for the epileptic. It is cluttered and jangly and tries to sell you every square inch of someone’s soul or something. Just focus on the interview.

Noted: a dip in sales of Carver’s books. Why? Why, person who wrote “…a masterful biography rated by the New York Times as one of the best 10 books of 2009”?

For one thing, he was too much imitated and for another, it is usually more important for younger writers to look at living writers.

The imitation thing is one persistent myth, I’ll say that. Is it really more important for younger writers to look at living writers? I absolutely disagree, and my MFA program disagreed, and I am thankful.

David Foster Wallace and Imagining Moral Fiction

David Foster Wallace was never doing anything wrong. Even Wallace’s first published story, “The Planet Trillaphon as It Stands in Relation to the Bad Thing”–published in 1984 by the Amherst Review, written presumably at the age of 22–bears most of his stylistic earmarks circa Infinite Jest, and grapples with themes that would echo throughout much of his work to follow: infinity, fear, the risk of autobiography, fiction as an event, the struggle to empathize–the struggle to simply be in one’s own skin. All of this with a keen and self-aware sense of humor which dares you not to let Wallace’s cheeky, vigorous and, behind all that, ultimately hurt voice crawl into your head and stay there. But toward the end of his life, Wallace wasn’t sure, any longer, if his stylistic approach to the themes he felt to be most urgent–the themes that ran, almost doctrinairally, obsessively, through both his fiction and nonfiction–was truly effective in the big, big way he wanted it to be. He wanted to pare down the ecstasy of his prose, empty his sentences of self in a move toward mindfulness, toward sacrifice. Partly, I think Wallace’s stylistic shift (which we will see in full force soon when his final, unfinished novel, The Pale King, hits) was simply him doing good work; no artist as intelligent and unremittingly inventive as Wallace could stay working in the same mode for long. But and also (just kidding; I won’t do that here), I think Wallace, the whole time, imagined his work as a call-to-arms to the writer inside of every reader, the reader inside of every writer. In his essay “E Unibus Pluram,” Wallace points toward exactly the kind of shift in literary consciousness–and moral consciousness–away from what he saw as the destructive impulses of postmodernism, the shift which he could never, for whatever reason, fully effect in his own work:

The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of ‘anti-rebels,’ born oglers who dare to step back from ironic watching, who have the childish gall to actually endorse single-entendre values. Who treat old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point, why they’ll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk things. Risk disapproval. […] Who knows. Today’s most engaged young fiction does seem like some kind of line’s end’s end.

I want to concentrate on Wallace’s understanding of the fictionist as, essentially and necessarily, an artist concerned with ethics, with how and why we do the things we do, with aesthetics as absolute freedom, with evil and with personal truth–truth concealed by a lie. And I want to ask why we are not more concerned with his vision. Why we do not, by and large, see aesthetics as ethics, as an ethical act, a metapolitics, for which we, as writers with the power and duty to transform, are deeply and inescapably responsible. And how we get from ethics to moral literature: literature with deep conviction and passion toward the event of truth.

GIANT Review: Mathias Svalina’s Destruction Myth

Published by Cleveland State University. $15.95, 83 pages.

[NOTE: The author of this review discloses a high personal regard for the author of the book under consideration.]

The first forty-four of the poems in Mathias Svalina’s Destruction Myth are called “Creation Myth”—that’s all of them except the very last one, which happens to be the title poem. It would be easy enough, and also probably correct, to read deeply into the title, locate there the thematic and/or philosophical and/or theoretical matrix that centers and informs the work. One could go off on the whole thing about how all creation is in some sense a destructive act (even ex nihilo creation requires a rending of the nothingness that exists prior to thingness), or, better still, how even as creation is ongoing and ever-renewing, we can never escape the essential fact of destruction: the limitless variety of creation, for all its glory, can never not be overshadowed by the singular fact of destruction, the final and re-unifying change that awaits us all. But to be perfectly honest, I’d rather not get into it, because there are few things duller than diligent, well-intentioned exegesis, and a book as big-hearted and bonkers as this one deserves better.

January 25th, 2010 / 12:31 pm

Literary Dopplegangers

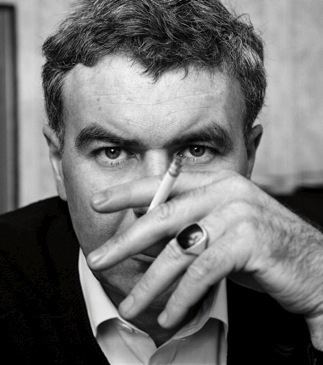

Justin Taylor and Priestess singer/guitarist Mikey Heppner

Gain some weight. Grow your hair out. Off you go.

(Jimmy Chen blackmailed me into putting this up. Sooooo:

Berobed Jimmy Chen and berobed rapping Buddhist monk Mr. Happiness

Gain some weight. Keep your hair short. Off you go.)

Additional material after the cut. READ MORE >

Justin is on Electric Literature and the story’s kinda badass. E.g.: “I don’t know dick about Latin but some things are just obvious and sometimes I think that’s what God is: the obvious, resplendent and intractable and dumb.” (Sorry I didn’t notice this sooner.)

Kareem Estefan Gets “Jerk” Right at BOMB

When I lashed out at the shallow, willfully ignorant, and overwhelmingly useless NYT review of Jerk, some commenters–in particular a very nice guy named Sean Carman–challenged me to go beyond merely pillorying Neil Genzlinger for the miserable job he did*, and articulate some sort of affirmative vision of the piece and of Dennis Cooper’s work in general–what it means to me, a study of how it functions, and so on. I’m on-record any number of places about my admiration, respect, and enthusiasm for Dennis’s work–so that information is out there if people want it. With regard to Jerk in particular, I want to point people to this review by Kareem Estefan, published yesterday at the BOMB site, which I think says all the things I might have said, only better than I probably would have said them.

Vienne’s Jerk traces a receding path of voices, as scenes of traumatic memory play in the hands of the audience, on Capdeville’s knees, and finally, within the actor’s body. Do we get closer to understanding trauma as we follow this progression? Are we more or less capable of empathizing with the abused, repentant murderer as we read, watch, and listen to such disfiguring acts? Vienne, Capdeville, and their collaborators dismantle the psychic space of the subject much as Cooper jerks from fragment to fragment of an event that cannot be represented.

Estefan seems to be more or less all the things one hopes a critic will be–attentive, perceptive, engaged, and smart. His essay considers the work in all of its nuance: the adaptation of the short story into a performance-piece, the staging of the work in the very basement-y PS122 theater-space, and of course the performance itself. His goal is not to force an up or down vote, as thought the work were an American Idol contestant; he endeavors rather to understand the work on its own terms, and to communicate that understanding for the benefit of his reader. This is the best piece of criticism of Jerk I’ve read yet, and I encourage all of you to read it. This is the first time I’ve read anything by Kareem Estefan, but he’s on the radar now, so hopefully we’ll be hearing from him again soon.

Also, for those of you who expressed an interest in learning more about Cooper’s poetics, you should let him tell you in his own words. This conversation between Blake Butler and Dennis Cooper, conducted by Alec Niedenthal at a cafe in the East Village and posted to our site late last night, is phenomenal. I was sitting at the table, in delighted silence, for an hour while these guys talked shop–it was magic, and that feeling seems to have survived transcription.

*[UPDATE: that post has been removed from this site. A lot of people thought I shouldn’t have posted it in the first place, and still others urged me to take it down. While my position on the review hasn’t changed at all, I’ve decided that everyone was better off without that ugliness in the world.]

Brief, but interesting: Lincoln Michel on DFW, Junot Diaz. Begs to ask the novel of the ’80s, the ’70s, the ’60s, ’50s…?

A Common Ography

As a teaser to the forthcoming Kevin Sampsell week, here today in celebration of the release of his new book, A Common Pornography, Kevin offers some tips for that potentially awkward exchange at the bookseller’s counter, if you’re touchy about that kind of thing:

I’ll wait until Sampsell week to dig deeper into the pleasure of this book by my label-brother, but I can honestly there hasn’t been one that made me feel sentimental for awkward years and at the same time edging along the form of communicating that station, well, I can’t remember one ever. Kevin nails so hard a certain kind of maturation period, re: masturbation, weird fathers, prostitutes, porn, all delivered in a cleaner, simpler, but just as smart Lutz-ian style, you are going to really like ACP.

Finally, all Borges fiction collected. Like your kidneys, a local library, or a reliable bowl–this you need. [Edit–it has been out 10 years] [Edit–beer] [Edit, still read it, though.]