A Bookseller’s Reading Snapshot

I like to hear about people’s reading habits—not just what they’re reading, but how. In the middle of the night, first thing in the morning, on the train, on the toilet, three books at a time, strictly poetry, in a deep musician biography phase—whatever. I like to hear when people are struggling to read—maybe because they can’t find the time or can’t find a book that holds them, maybe because they’re in the throes of grief or just having too good a time. It occurs to me every once in a while that some people just don’t care about books the way I just don’t care about, say, golf. Part of my job, if I’m being completely honest, is to make books look good, and make the reading life look good. I need people to buy in to the idea that owning stacks of books is important, that books are worth spending money on, especially since it’s entirely possible to own zero books and read as many as you want for free. I love this challenge. I hate capitalism but I love selling books, talking about books, and trying to learn as much as I can about why and how people read.

The place, generally speaking, where I feel most “free” to read, is in bed, before sleeping, after I’ve written in my five-year journal. I started my Tamara Shopsin journal three years ago and I cannot sleep until I’ve written something down—it’s a mental logging off for me, downloading my day somewhere safe and physical, which frees me to read without Bowsers from the day sneak-attacking my brain, enticing me to regret what I said to so-and-so or how I handled xyz parenting situation. Not now, Bowser! I’m reading. I also work hard to clear swaths of daytime hours on the weekend at least a couple of times a month, actually schedule this as I would a doctor’s appointment. Otherwise it won’t happen. The rest of my reading happens catch-as-catch can, while I’m waiting for other things, when I have a surprise thirty minutes, etc.

I read a lot because that’s my job, and it’s my job, in many ways, because I read a lot. The reading a lot part came first, and led me down a very winding path to where I am now. Here’s what I’ve been reading:

READ MORE >Walking with Dog & Sylvia

Nothing is more difficult than lashing a vagrant mind suddenly into long self-imposed stints of concentration.*

See the trees, the sidewalk, the trash can turned over, the Auburn flag, the dirty awning, the abandoned tricycle that will never not suggest something sinister. See the leaves, the dried ones on top and the molted ones beneath. See the neat ranch home, the Spanish colonial, the craftsman. Barking, birds, voices. Don’t think about what anything reminds me of. Don’t think about my childhood. Oh, my God–daffodils. Never not shocking with their yellowness, their alien mouths. Stop thinking about Sylvia Plath. Stop thinking about trying to write about her, the experience of re-reading her, the sex scene in THE BELL JAR that causes Esther to hemorrhage in a historical way, the rarest sex in the universe, the day-off-from-the-mental-hospital sex, the sex that punishes, the sex that touches death. How can the bleeding out not symbolize Plath herself, her genius, the violence she must have believed was embedded in her own ambition, in the very anatomy of female ambition.

So many cracks in the sidewalk, it would be impossible to play that game. Forgetting to remember and remembering to forget yield the same result: forgetting. A bird, another bird, so many birds. Too many birds today. How a certain number of birds signifies spring but one more than that number means something terrible is about to happen.

I want to live each day for itself like a string of colored beads, and not kill the present by cutting it up in cruel little snippets to fit some desperate architectural draft for a taj mahal in the future.

I am not an ‘in the moment’ person. The moment pains me with its borderlessness: how long will this last? When can I call it ‘over’? When can I call it the thing that came right before the real thing? When I was a child I sat in the church pew and was transmogrified by my longing for the service to be over. I mean I felt my blood blacken with disquietude, my limbs actually tingled. Sit still, my mother would say, but I would be sitting absolutely still. She could feel the friction in my mind, in my body, and it broke her concentration. Now, when I need to endure something I don’t want to endure, or when I need to wait for something, which I am still terrible at, and I can’t read or look at my phone, I try to pray, for something to do, and because that childhood pew was a crucible where my early ideas of God and suffering and forbearance and waiting got forged.

I’m newer to breathing as a form of coping. I used to become angry when people would talk about deep breathing. I like my breaths fast and shallow. Stop telling me to breathe, world. Stop telling me to slow down. Now I tell myself to breathe, to slow down. Mailbox, mailbox, crushed can, tire-flattened box of Eggos that must have escaped the recycling bin.

I catch up: each night, now, I must capture one taste, one touch, one vision from the ruck of the day’s garbage. How all this life would vanish, evaporate, if I didn’t clutch at it, cling to it, while I still remember some twinge or glory.

My dog–a phrase I never thought I’d say–sniffs everything. As though every day he sets out with one goal: to sniff every single thing. I pull him along, before remembering that I’m not supposed to be hurrying, I’m supposed to be pretending that time doesn’t exist, that all of these things around me are the miracles they’d be if I were a better person, or an animal. A chimney. A brick. So many bricks. I can’t fathom being tasked with building a house, or even just making a single brick. Trees, plants, grass–so much green and I only have the barest understanding of photosynthesis, of the very air I’m abusing. I have no practical skills, my God. Look at those bricks and meditate on the people who know what to do with them. Look at the litter without judging it. Stop judging the litter. The well-swept porch, the shabby car. This is not a cookie-cutter neighborhood. This is a real neighborhood. There is so much to see, if I could just stay with it, stay in the seeing, in the indexing, and out of the dictionary part, where meaning must be ascribed, or the memory part, where connections must be drawn. My dog eats garbage.

I keep believing that the world is loving because I am. I keep waiting for something to jump out of the bushes and harm me, but nothing harms me like I harm myself.

There is a certain clinical satisfaction in seeing just how bad things can get.

*All italicized portions are from The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, ed. Karen V. Kukil

His Geography: The Collected Works of Michael Ondaatje

A. “There are stories the man recites quietly into the room which slip from level to level like a hawk.”

The English Patient

1. A popular mistake about Canada is that it is fundamentally North. Otto Friedrich’s biography of Glenn Gould compares Canada’s relationship to the North with America’s to the West, except there’s no Disneyland in the Arctic. Most of Canada’s population is concentrated in the southernmost quarters; post-Gould Toronto produced Petra Collins’ Instagram, among a lot of other non-Drizzy things. One quarter of all postwar immigrants to Canada came to Toronto. Canada’s history is only one centennial in; its youth relative to the rest of the world may account for why the rest of the world sometimes acts so strange about it. Cats still aren’t sure about humans because in evolutionary terms they haven’t been around as long as dogs and are still socializing themselves. There are no cats in the Bible, for instance.

2. The book of 2014, nonfic anyway, was Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty, a book carrying the mythical glow of pregnancy. Stephen Marche reviewed it for the Los Angeles Review of Books, calling it ‘perhaps the only major work of economics that could reasonably be mistaken for a work of literary criticism.’ He relates realism’s utter defeat of the other forms, the fun ones like lyricism or even minimalism, and credits Jonathan Franzen, that old serpent, with its proliferation. We already knew all that. One of the writers Marche suggests has fallen out of usage is the Canadian Michael Ondaatje: from Ontario by way of Sri Lanka, educated in England, known for hushed, haunted pieces like The English Patient (1992), Divisadero (2007) and The Collected Works Of Billy The Kid (1970). He also wrote a memoir, Running In The Family (1979), which includes the following clip:

“At St. Thomas’ College Boy School I had written ‘lines’ as punishment. A hundred and fifty times. [fragment in Sinhalese] I must not throw coconuts off the roof of Cobblestone House. [fragment in Sinhalese] We must not urinate again on Father Barnabus’ tires. A communal protest this time, the first of my socialist tendencies. The idiot phrases moved east across the page as if searching for longitude and story, some meaning or grace that would occur blazing after so much writing. For years I thought literature was punishment, simply a parade ground. The only freedom writing brought was as the author of rude expressions on walls and desks.”

3. Ondaatje’s family is Dutch-Ceylonese and was well-off. By various vagaries his father ended up a chicken farmer, his mother on staff at a hotel, and he and his siblings diffused thru England, America, and Canada. Much of his writing is liminal: the act of falling on a map, and why is it called falling? ‘We are the real countries’, vows a character in The English Patient. Disdain for colonialism and its legacies is a chief Ondaatje engine; another character in The English Patient insists that everyone white is motivationally English: ‘when you are bombing brown races you are an Englishman’. That character’s name is Kim and he’s Sikh, which we know because he wears a turban. Almasy, the sophisticated count burned into patienthood if not Englishness, is Hungarian but nomadic. He hates ownership, being owned—and the idea that when there’s a war on, where you’re from becomes important.

Ondaatje produces fantasias of language, requiring much suspension of disbelief, risking collapse if pulled too far out of context. As stated by Pico Eyer in an essay for the New York Review of Books called ‘A New Kind of Mongrel Fiction’: ‘ there will always be some for whom Ondaatje is too rarefied or exquisite.’ Lines like ‘giraffes of fame’ and little leashes of them like ‘later my hands cracked in love juice/fingers paralyzed by it arthritic/these beautiful fingers I couldnt [sic] move/faster than a crippled witch now’ qualify as sentimental dithering to the worst agnostics. Glenn Gould said he believed in God as long as it was Bach’s; I believe in a groundless, fermented prose style as long as it is Ondaatje’s. Even when it’s a little bit bad, it is never not beautiful.

‘There is nothing wise about a harbor, but it is real life. It is as sincere as a Singapore cassette. Infinite waters cohabit with flotsam on this side of the breakwater and the luxury liners and Maldive fishing vessels steam out to erase calm sea. Who was I saying goodbye to?’

Ondaatje, Running In The Family

October 3rd, 2014 / 10:00 am

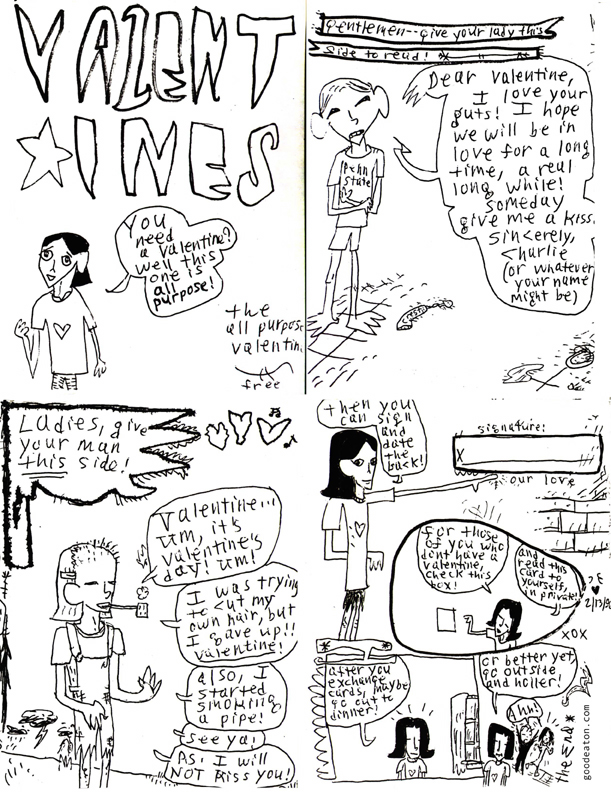

Tom Eaton’s Valentine

An oldie but goodie. (2/3/96? Sheesh!) Printable/foldable version here (PDF).

Happy Valentine’s Day, HG. Someday give me a kiss.

A Tiny Addendum to Paul Auster’s Concept Concerning “Boy Writers”

On 16 January 2014, a writer boy named Paul Auster conversed with someone named Dr. Isaac Gewirtz (this boy likely had friends & relations who were a part of the Holocaust) at the Morgan Library (which seems quite splendid, though it may not be if Mayor Bloomberg was able to blow his matzoh-ball-soup breath on it).

According to girl writer & Huffington Post blogger Anne Margaret Daniel, Paul put forth the category of a “boy writer,” which means:

someone who is so excited, takes such a sense of glee and delight in being clever, in puzzles, in games, in… and you can feel these boys cackling in their rooms when they write a good sentence, just enjoying the whole adventure of it. And the boy writers are the ones you read, and you understand why you love literature so much.

I concur with Paul — because of “boy writers,” literature is the best thing ever (except Christianity).

Arthur Rimbaud is a boy writer, which is why he stabbed people at poetry readings and yelled “shit” after the insipid readers declaimed their dull verse.

Edgar Allan Poe, as Paul points out, is a boy writer, as he composed stories on murder and poems on special girls, like the “beautiful Annabel Lee.”

There’s not a lot of boy writers who are un-dead. Most, nowadays, correspond to what Paul terms a “grown-up writer.” Stephen Burt, Carl Phillips, Dobby Gibson, Geoffrey G. O’Brien, Bob Hicok are examples of a “grown-up writer.” They don’t spotlight the “puzzles” and the “games” of the violence, theatricality, exploitation, and upsetness in the postlapsarian world. They document liberal middle class averageness. “It’s about settling down and settling in,” says Burt.

But some boy writers are un-dead.

Johannes Goransson likes makeup and violence. “mascara is infected / belongs to assaults,” the Action Books editor and boy writer elucidates in Pilot (Johann the Carousel Horse).

HTML Giant’s own Blake Butler is a boy writer. In Sky Saw, his characters aren’t given names but numbers (just like in the Holocaust and in the War on Terror). Reading his books are sort of close to witnessing a disembowelment.

Paul Legault (because he likes Emily Dickinson like someone would like an American Girl doll), Walter Mackey (because he likes Barbie), and Julian Brolaski (because his language reads like sticky, sweet, chewy watermelon bubblegum), are all un-dead boy writers.

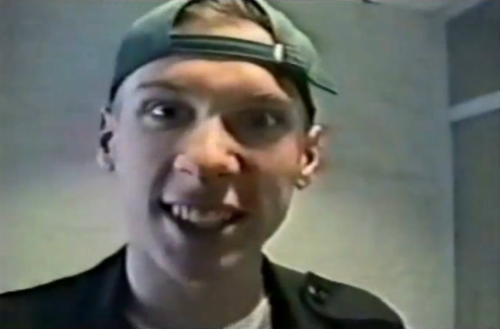

But the best boy writers (maybe ever) are dead, and they’re Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. Glee? Delight? Cackling in their rooms? Enjoying the whole adventure? All the attribute’s of Paul’s boy writer align with Eric and Dylan. They kept journals, websites, and videos so everyone in the whole wide world could be cognizant of the glee-enjoying-cackling-delight-adventure that they had in planning their massacre. As Eric stated, “I could convince them that I’m going to climb Mount Everest, or that I have a twin brother growing out of my back. I can make you believe anything.”

Boys Who Kill: Kevin Khatchadourian

The final Boys Who Kill for the time being brings the spotlight to Kevin Khatchadourian. On 10 April 1999, ten days prior to Dylan and Eric’s premiere of NBK, Kevin killed his daddy and his sister before going to school and murdering seven students, one English teacher, and one janitor in the gym.

Growing up, Kevin’s two favorite words, according to his mommy, were “Idonlikedat” and “dumb.” Whether it was his mommy’s milk, his mommy’s cooking, his mommy in general, music, or cartoons, Kevin’s would probably be displeased by it. Although, there are some things that Kevin does like, like computer viruses and Robin Hood. Both Robin Hood and computer viruses attack targets that possess plenty of materials. Robin Hood deprives rich people of their things and computer viruses deprive computers of their ability to preserve their multitude of files and functions.

Kevin’s granddaddy and grandmommy maintain a motto: “Materials are everything.” The granddaddy and grandmommy fill their lives by doing things. They install water softeners and purchase first-rate 1000-dollar speakers, even though they don’t really like music all that much. As for Kevin, his mommy says that he “was never one to deceive himself that, by merely filling it, he was putting his time to productive use.” While 99 percent of people spend their Saturday afternoons doing something, like speculating on what they intend to do that night or checking their social media feeds, Kevin is “doing nothing but reviling every second of every minute of his.” With a tough tummy, Kevin can do what the phony baloneys can’t: “face the void.”

Simone Weil has a similar perspective on life. For the French ascetic, nothingness is truthfulness since it has to do with God. “We can only know one thing about God: that he is what we are not,” says Simone in her notebooks. God isn’t composed of matter nor is he quantifiable. Unlike humans, there is no corporeal limit to God. He is infinite. Humans are a sham. They use their days trying to satiate various desires (hunger, thirst, xxx, and so on) even though these hankerings can never be permanently filled because human beings are really just one giant hole. As Simone declares, “Human life is impossible.” Simone and Kevin each confront the hopelessness of fulfillment in a material and fleshy existence. They each effect divinity through destruction — Simone destroys herself and Kevin destroy the things and people around him. READ MORE >

Boys Who Kill: Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb

The third installment of Boys Who Kill stars Nathan Leopold (right) and Richard Loeb (left). On 21 May 1924 in Chicago, Nathan and Richard kidnapped and killed a 14-year-old boy.

Nathan and Richard each had daddies who amassed mountains of money. Nathan’s daddy owned one of the biggest shipping business in the country and Richard’s daddy was the vice president of Sears Roebuck. But the wealth that surrounded them didn’t dispel boredom. The two didn’t want money, they aimed for fame, sensationalism, and transgression. One of Richard’s favorite dreams had him as a notorious criminal who was beat and whipped in public, with girls and boys arriving in droves to express their mixture of awe, sympathy, and disgust. As for Nathan, he envisioned himself as a king’s favorite slave. One day, Nathan saved the king’s life, and the king offered to set him free, but, being loyal, Nathan declined. Both fantasies are rather Jean Genet: they are sumptuous, romantic, and somewhat sordid.

Like that French prison boy, Nathan and Richard carried out many crimes, including stealing automobiles and smashing bricks through windows. Mostly, though, the crimes were initiated by Richard, who insisted that Nathan come along to serve as an audience. After the two stole a typewriter and other possessions from Richard’s former frat house at the University of Michigan, Nathan became upset at Richard because the latter wasn’t wasn’t having enough xxx with the former.

Nathan and Richard’s friendship/boyfriendship sort of resembles the typical depiction (though it’s likely bullcrap) of Eric and Dylan. Eric is the aggressor and Dylan is the follower. Eric constructed NBK and Dylan just acquiesced. It’s also been rumored that Eric and Dylan liked boys (though that’s definitely bullcrap). Columbine jocks told the media that the two BFFs were a part of the Trench Coat Mafia, whose members touched one another in hallways and convened group showers. In Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, the two Columbine-esque boys get into the shower together and kiss and maybe do other things before they commit their high school massacre.

But Nathan and Richard really did like boys. Though Richard was perceived as the leader, he was the one who took it in the tushy. That this is so, sort of confounds how boys who take in the tushy are assessed. Richard engineered many crimes, including murder, so maybe boys who take in the tushy aren’t all basic bitches after all. Another hypothetical reason for why Richard took it in the tushy is, as he declared to friends, he didn’t need xxx. Richard was beyond lust and all of that other stuff that occupies the ironic minds of 20-something Brooklyners day and night. The symbolism about taking it in the tushy had no effect on him, as he only cared about a life of crime.

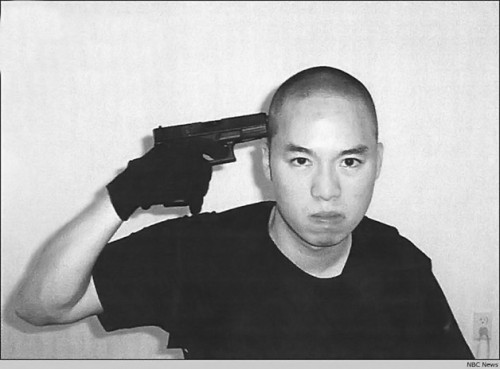

Boys Who Kill: Cho Seung-Hui

The next installment of Boys Who Kill stars Cho Seung-Hui, or Seung-Hui Cho, or Question Mark. On 16 April 2007, 4 days before the 7th anniversary of Columbine, Cho killed 32 people at Virginia Tech. First he visited West Ambler Johnston Hall, a dorm room for both boys and girls, where he killed one boy and one girl. Then he traveled to Norris Hall, a classroom building, and killed 30 more people.

Ever since Cho was taken out of his mommy’s tummy he hasn’t taken to talking. “Talk, she just him to walk,” says Cho’s great aunt about his mommy. “When I told his mother that he was a good boy, quiet but well behaved, she said she would rather have him respond to her when talked to than be good and meek.” At Virginia Tech, one of Cho’s roommates remarked, “I would see him walking to class and I would say ‘hey’ to him and he wouldn’t even look at me.” Other students concluded that he was a deaf-mute. He ate myself all by himself, and when someone offered him 10 dollars to say something, he said nothing. According to medical professionals, Cho suffered from “selective mutism.”

I, too, would prefer to be mute, and so, it seems, do other boys. Holden Caulfield dreams about being a deaf mute, and, it’s been reported by various biographers that instead of engaging in dinner table conversation, Arthur Rimbaud would just growl. Talking is terribly human — this race of creatures does in it grotesque quantities: they talk at Whole Foods, at overpriced bars, at trendy coffee shops, and, obviously, through Gmail, Gchat, texts, Facebook, Twitter, Disqus, and so on.

Cho’s contempt for normal communication distinguishes him from humans. Virginia Tech students and teachers constantly construct Cho as boy who confound expected human behavior. A professor labeled him “disturbing” and “unusual.” A student in his playwriting class said Cho “was just off, in a very creepy way.” According to Nikki Giovanni, students started skipping her poetry class due to Cho’s behavior . When Nikki told him to either cease composing sinister poems or drop her class, Cho replied, “You can’t make me.” Eventually the then head of the English Department, Lucinda Roy, tutored him privately. But even Lucinda was afraid of him. During the one-on-one tutoring appointments, Lucinda and her assistant agreed upon a code word that would prompt the assistant to summon security when uttered.

Based on this testimony, Cho is similar to a virus or a disease. No one wants to be around him; everyone is horrified of his presence. Not one to stay up into the wee hours of the morning to drink, party, and partake in sexual intercourse, Cho went to bed early and awoke early. He also played basketball alone. According to the New York Times, Cho was in a “suffocating cocoon.” (Being in a “suffocating cocoon” seems very dramatic and cosy; it also seems as if a “suffocating cocoon” would provide protection from mankind.) Virginia Tech journalism professor Roland Lazenby sums up Cho as a “shadow figure, locked in a world of willful silence.” Both Lazenby and the Times portray an incomprehensible boy who, isn’t free and liberated like Western subjects, but is held captive by a dark dangerous force. As Theresa Walsh, a girl who witnessed the killings in Norris Hall, says, “I’ve never really thought of him as a person. To me, he doesn’t have a name. He’s always been just the ‘the shooter’ or ‘the killer.'”