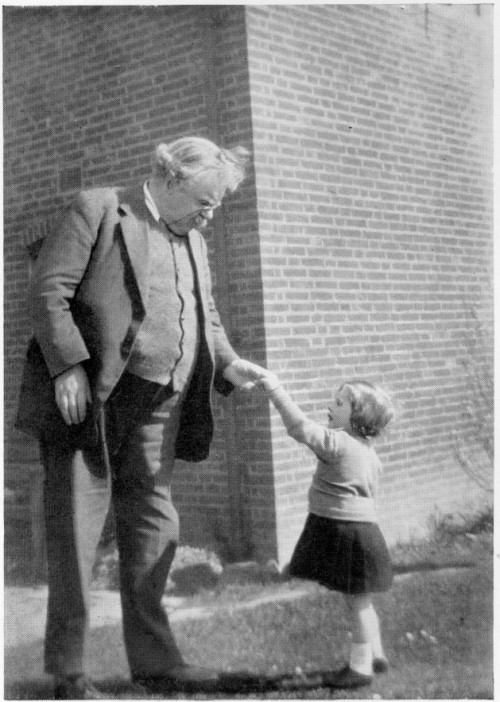

G.K. Chesterton (4)

We are perhaps permitted tragedy as a sort of merciful comedy: because the frantic energy of divine things would knock us down like a drunken farce. We can take our own tears more lightly than we could take the tremendous levities of the angels. So we sit perhaps in a starry chamber of silence, while the laughter of the heavens is too loud for us to hear.

– Orthodoxy

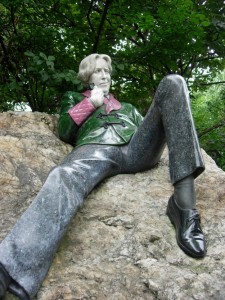

Critics on Criticism: Oscar Wilde

From “The Critic as Artist”:

From “The Critic as Artist”:

To the critic the work of art is simply a suggestion for a new work of his own, that need not bear any obvious resemblance to the thing it criticizes. The one characteristic of a beautiful form is that one can put into it whatever one wishes, and see in it whatever one chooses to see; and the Beauty, that gives to creation its universal and aesthetic element, makes the critic a creator in his turn, and whispers of a thousand different things which were not present in the mind of him who carved the statue or painted the panel or graved the gem.

G.K. Chesterton (3)

The following propositions have been urged: First, that some faith in our life is required even to improve it; second, that some dissatisfaction with things as they are is necessary even in order to be satisfied; third, that to have this necessary discontent it is not sufficient to have the obvious equilibrium of the Stoic. For mere resignation has neither the gigantic levity of pleasure nor the superb intolerance of pain. There is a vital objection to the advice merely to grin and bear it. The objection is that if you merely bear it, you do not grin.

–Orthodoxy, “The Eternal Revolution”

Chesterton Redux

We have all read in scientific books, and, indeed, in all romances, the story of the man who has forgotten his name. This man walks about the streets and can see and appreciate everything; only he cannot remember who he is. Well, every man is that man in the story. Every man has forgotten who he is. One may understand the cosmos, but never the ego; the self is more distant than any star. Thou shalt love the Lord thy God; but thou shalt not know thyself. We are all under the same mental calamity; we have all forgotten our names. We have all forgotten what we really are. All that we call common sense and rationality and practicality and positivism only means that for certain dead levels of our life we forget that we have forgotten. All that we call spirit and art and ecstasy only means that for one awful instant we remember that we forget.

– Orthodoxy, Chapter Four, “The Ethics of Elfland”

Wack Bible Stories

You know Jonah – God sent him to Ninevah but he didn’t want to go, so God made a whale eat him. Then Jonah had a change of heart and God made the whale barf him up.

You know Jonah – God sent him to Ninevah but he didn’t want to go, so God made a whale eat him. Then Jonah had a change of heart and God made the whale barf him up.

Here’s the rest of the story: in Ninevah, Jonah told everyone that God was going to wipe them out in 40 days. They panicked and dressed themselves in burlap and the king said no one should eat anything. He said no animals should eat anything either, so God spared them. This irked Jonah because he looked like he didn’t know what he was talking about. Surely thinking about the Mediterranean storm, this time he fled into the desert. That night God grew a plant to shade Jonah. Then God sent a worm to eat the plant.

It’s in the Bible: READ MORE >

Classic but Yeah

“I don’t do drugs. I am drugs.”

Critics on Criticism: Susan Sontag

From title essay of Against Interpretation:

From title essay of Against Interpretation:

What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.

Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.

The aim of all commentary on art now should be to make works of art–and, by analogy–our own experience–more, rather than less, real to us. The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.

In place of hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.

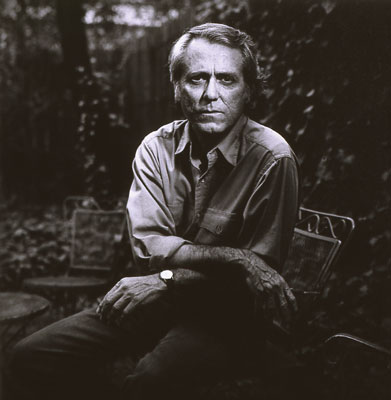

Power Quote: Don DeLillo

Every sentence has a truth waiting at the end of it and the writer learns how to know it when he finally gets there. On one level this truth is the swing of the sentence, the beat and poise, but down deeper it’s the integrity of the writer as he matches with the language. I’ve always seen myself in sentences. I begin to recognize myself, word by word, as I work through a sentence. The language of my books has shaped me as a man. There’s a moral force in a sentence when it comes out right. It speaks the writer’s will to live. The deeper I become entangled in the process of getting a sentence right in its syllables and rhythms, the more I learn about myself.

– Mao II

Power Quote: G.K. Chesterton

Mysticism keeps men sane. As long as you have mystery you have health; when you destroy mystery you create morbidity. The ordinary man has always been sane because the ordinary man has always been a mystic. He has permitted the twilight. He has always had one foot in earth and the other in fairyland. He has always left himself free to doubt his gods; but (unlike the agnostic of to-day) free also to believe in them. He has always cared more for truth than for consistency. If he saw two truths that seemed to contradict each other, he would take the two truths and the contradiction along with them. […] The whole secret of mysticism is this: that man can understand everything by the help of what he does not understand.

– Orthodoxy

In which I kick off ‘Mean Week’ with a quote from Lyn Hejinian that seems to implicate us all

Whether by fate, chance, contingency, purposelessness, irrelevance, or best

of all, uncertainty, we are thrown around, sometimes

at each other, and no matter whether the narrative is plot-based

or character-based, we are thrown from each other

in the end, carrying borrowed being, turning round

and round. “I’m going to color outside

the lines of reggae,” A proclaims; scenery makes a difference

and with it a new personality, but what about the dog

gazing rapturously into A’s face? It’s clear that he or she is alert

to small phrasings as well as to the water level

in the creek. But, in the end, he or she will drown

in the type of creek it seems to be, a flow of sympathy

over rocks, silt, the bones of a mule, past

laurel trees and sunbathers, under suds

and water-skeeters, to Mexico and the Pacific

and to xerox — as if that would keep things

in print. To pull experience out from under

the floating oak leaves would be an act of ingratitude

and betrayal. But to meet K and M would be an honor

and a pleasure as long as no one expects me to speak.

– The Fatalist, pp. 71-72