On László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below

Translated from the German by Michael Hulse

Excerpts from Seiobo There Below translated by Ottilie Mulzet

This article on László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below, a novel just released from New Directions Publishing, originally appeared in German in Die Zeit on September 2, 2010, and its translation was commissioned and published by Music & Literature Magazine on the occasion of their second issue, devoted entirely to the creative cosmos of Mr. Krasznahorkai. This special issue is available for purchase through their website. You can also read an interview with M&L editor-in-chief Taylor Davis-Van Atta here. Follow the editors of Music & Literature on Twitter at @musiclitmag and @CWTParis.

***

These stories are about the sacred. Their high artistic character is not in question for a single moment: the flow of the sentences, frequently continuing over pages and broken up only by commas, is captivating; the stories’ forceful progression toward the moment when the sacred appears is masterly; the connection of the separate sections by a half-concealed group of motifs and their arrangement into a Fibonacci sequence are irresistible.

As if this achievement were not enough, after two or three stories an unnameable, haunting quality, beyond all the beauty of mere appearance, emerges from the aesthetic pleasures offered by Krasznahorkai’s unusual prose. We sense how the stories challenge us as readers; we begin to argue and debate with them. Are they right, or are we? “They” are the Russian Orthodox monks under the spell of icons, the Japanese Buddhists under the spell of a Buddha statue, the despairing Westerner unexpectedly under the spell of a Renaissance Christ. With Krasznahorkai, something has returned to art that was taken for granted and considered essential by Dostoevsky, and that has since then become more than a little diluted: the question leading toward the truthfulness of life.

Krasznahorkai brings his enlightened, relativist present-day Westerners, alienated to a greater or lesser degree, face-to-face with the absolute demands that the sacred makes of existence. The medium through which the sacred speaks in his work is the sacred art of the past, approached in stories that, by the author’s account, often have an autobiographical basis. Readers who may themselves be indifferent to religion will not find themselves repelled by this book, with its breathtaking diagnosis of the times. For Krasznahorkai is no preacher: the dimension in which he works is one of questing, inquiring, doubting. Any overweening earnestness is undercut with the irony that accompanies his often eccentric seekers on their path. And he evades the greatest danger of all, inflated pathos, with the most surprising of his stratagems: while he writes of art purely as an expression of the sacred, he does so in the unemotional key of a scholarly expert discoursing on the technical aspects of art history. Hence the Russian icons are, on the one hand, windows through which there shines a world beyond this one, and through which we may gain visions of the hereafter, yet, on the other hand, the religious narrative is directly confronted with a strikingly well-informed art-historical essay on the traditions and techniques of icon painting.

The luminous inner view and the profane external perspective of the holy are assigned a particularly convincing opposition in the story “He Rises at Dawn.” It describes the work of mask-carver Ito Ryosuke over a period of almost two months completing a Hannya mask for the Noh play Aoi no Ue. We witness every one of the minute steps in this procedure, in great detail and with atmospheric intensity, from the transfer of the stencil lines onto a piece of hinoki cypress wood until the completion of the masterpiece, which marks “[that] his hands have brought a demon into the world, and that it will do harm.” For his work, the carver withdraws into a wooden box he has made, to have perfect silence and seclusion. And yet it is not altogether certain who exactly is performing the work. For the carver does not think or plan anything; “within him there is no desire for the exquisite”; “his head is as empty as if he had been stunned by something, only his hand knows, the chisel knows why this must happen.” Only his hand—and his eyes. Again and again, he holds the mask-in-progress at arm’s length, comparing it with the stencil and with two photographs inside his work box: “this is the model, the ideal to be sought, this is what he must, in his own way, be equal to.” A time comes when his hand and eyes are no longer equal to the task unaided, and he lends support to his eyes with a “system of mirrors,” tilting and revolving mirrors which he installs around the box.

This gaze is contrasted with the external, intellectualized perspective of Western visitors, who pester the carver with “dreadfully tactless questions.” The Westerners want to know “what is the Noh, and what is the meaning of the hannya-mask, and how can there be ‘something sacred’ from a simple hinoki tree.” To the carver, their interrogation is a confusing tangle of questions, to which he can only stammer the briefest of replies: “…he does not occupy himself with such questions as what is the Noh, and what makes a mask ‘spell-binding,’ he merely occupies himself with doing the very best he can within the limits of his abilities, and with the aid of prayers recited secretly in shrines, he only knows movements, methods of work, chiseling, carving, polishing, that is to say, the method, the entire practical order of operations of tradition, but not the so-called ‘big questions.’”

In this way, the story reflects a certain polarity of East and West, at once steeped in the ethnographic nature of a craft and at the same time religious. The hand and its unconscious actions appear in opposition to the head and its questions about meaning; we find here the contrast of intellectual reflection and the external reflection from the system of mirrors. Indeed, most of these stories revolve around fundamental issues in philosophy. One of Krasznahorkai’s protagonists, at loose ends, attempts by a superhuman effort of the will to see the Acropolis on a hot summer’s day. But he sees nothing at all, blinded by the glaring sunlight and his own sweat, and at the end of the story he decides to return to a group of Athenian friends who have renounced all strivings of willpower and individual endeavor and simply do nothing all day.

The key philosophical motifs in these stories are of being overwhelmed, beaten down. Of one character’s response to an angel in an icon we read: “almost immediately at the sight he collapsed.” Of Baroque music: “it subdues one, breaks one’s heart to bits, knocks one to the ground.” A visitor to the Alhambra is “is so stunned by the beauty, by this beauty that is so, but so unbelievably beautiful that he thinks he is struck by vertigo,” where “a truth never before manifested reveals itself.” And a museum attendant who has been devoting his entire attention for decades to the Venus de Milo is “mesmerized,” “feet rooted to the ground.”

Krasznahorkai does not shy away from superlatives when he aims to convey the presence of the “celestial realm.” But, despite the philosophical appurtenances and the essayistic appearance, these stories are not sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought. For the concepts and superlatives are no more than buoys bobbing on the mighty current of Krasznahorkai’s prose. This musical river of language is the true event of this book, and is overpowering in itself. The current lifts up the reader, drags him down, catches him in whirlpools, is caught still, races across rapids, and with all of these qualities generates an experience that bars us from any distanced reading of the stories but forces us to live at the most intense pitch. It is impossible not to identify with these lonely, despairing, tired-of-life or just plain eccentric characters led by Krasznahorkai toward their moment of truth. We are drawn so close to them that it continually astonishes us when we realize that the stories are told not in the first but in the third person.

Of course, what we see here is yet one more balancing act by the great storyteller, László Krasznahorkai: just as he can be essayistic without slipping into didacticism, and emotional without turning bathetic, so too he remains wary of assigning the central position to his solitary and despairing characters, reserving that place to the current that tears everything with it—in one moment narrative, in the next meditative and interpretative—to the current of his prose.

***

Andreas Isenschmid has been editorial director at Schweizer Rundfunk, head of Literaturchef der Weltwoche, literary editor at the Tage-Anzeiger, among other distinctions. He now writes for the Hamburg ZEIT and is a critic on the program Kulturzeit.

The Kind of Girl

The Kind of Girl

Enon

Enon

Ferdydurke

Ferdydurke HOPE TREE

HOPE TREE

Y’all y’all y’all what if they made pumpkin spice American Spirits, I would shut down my self-governance, I would sit inside buying raffle tickets, like buying a million, and winning all the books. All the books? You can win the books. That’s real.

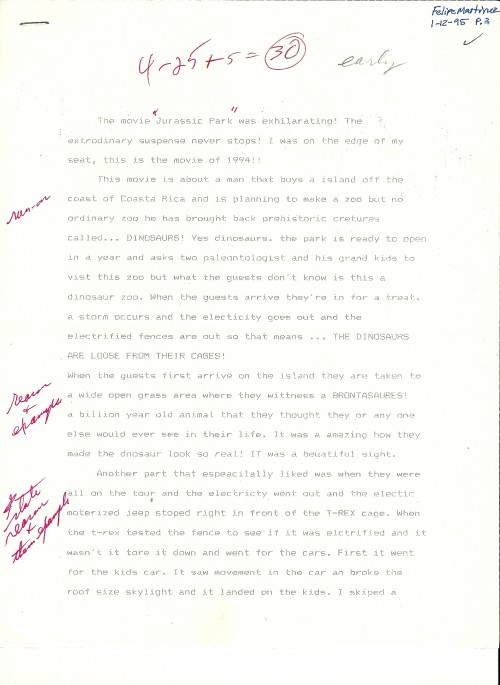

Y’all y’all y’all what if they made pumpkin spice American Spirits, I would shut down my self-governance, I would sit inside buying raffle tickets, like buying a million, and winning all the books. All the books? You can win the books. That’s real. Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park